|

|

|||

|

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

BALD CYPRESS: Last week we were on the South Carolina coast for a few days, giving "Hummingbird Mornings" presentations at Brookgreen Gardens, not far from Myrtle Beach. There were several hundred hummingbird enthusiasts in the audience, dozens of hummingbirds, and quite a few Bald Cypress--stately, water-loving trees that most people associate only with Low Country swamps. In reality, these days Bald Cypress is also a tree of the Piedmont, and we even have some growing at Hilton Pond Center almost 150 miles from the coast.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center For devotees of the Old South, it may be sacrilege to state that Bald Cypress grows away from the Coastal Plain. Indeed, one image that comes to mind when one says "Low Country" is that of ramrod-straight Bald Cypresses rising from the fog-laden swamp, festooned by Spanish Moss and surrounded by knobby "knees" that protrude from dark water around the trees' buttressed trunks. Despite this romanticized tableau, Bald Cypress grows quite well on sunny and relatively dry upland tracts in temperate areas across the eastern half of the U.S., and even north of the Mason-Dixon Line. Bald Cypress, Taxodium distichum, isn't really one of the cypresses; those trees are in the Cupressaceae--the plant family that includes Arborvitae and Western and Eastern Red Cedars--while Bald Cypress joins Coastal Redwoods and Giant Sequoias in the Taxodiaceae.

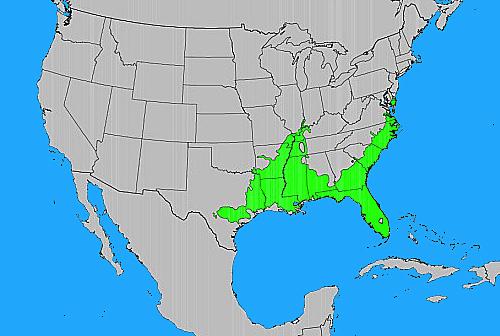

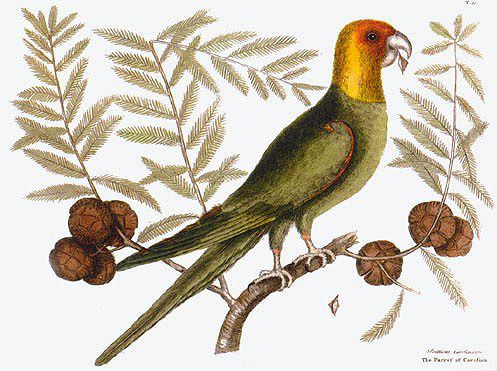

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Lumber from Bald Cypress is priced at a premium because it is sturdy, impervious to insects, and doesn't rot--which might be expected of a tree that often spends much of its life with its roots in water. Most of the really big Bald Cypresses were logged out across their primary historical range (green area on map above), but giant 500-year-old specimens with diameters of ten feet or more were still being cut as late as the 1970s in South Carolina. Today, some of the best stands of big Bald Cypress trees in the Palmetto State are in Congaree Swamp National Monument near Columbia, and a few majestic specimens have been saved in Beidler Forest, an Audubon sanctuary at Harleyville. Sadly, due to logging and resulting habitat loss, there aren't many giant Bald Cypress trees left, but a considerable number of smaller trees prosper throughout the eastern U.S. The fruit of the Bald Cypress is a hard, pear-shaped cone that turns brown and becomes woody as it matures (above right). Not many animals can open the tough fruit, so the vast majority of Bald Cypress cones fall to the ground beneath the tree that produced them--exactly where a seedling has little chance competing against its parent for sunlight in some dimly lit swamp. (Some seeds do float away on slow-moving waters and germinate elsewhere, but those all go "downstream.") Until the early 1900's, there was a natural solution to the conundrum of "long-distance" dissemination: the Carolina Parakeet. This colorful dove-sized bird had a hooked bill strong enough to open Bald Cypress cones, so the parakeet could spread a tree's seeds in its droppings over a considerable distance.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Carolina Parakeets, Conuropsis carolinensis, were common throughout the eastern U.S. when Europeans first arrived; in fact, in about 1740 Mark Catesby--perhaps the first great nature artist to paint American wildlife--rendered a portrait of this little parrot eating (of all things!) Bald Cypress seeds (see painting above). Unfortunately, people and parakeets had major conflicts because the birds foraged on orchards and corn crops, We can't imagine what it would be like these days to look out our office window at Hilton Pond Center to see a cloud of yellow, green, and red Carolina Parakeets chattering around a sunflower seed feeder, but it's unconscionable that humans could have brought about the demise of this once-common native species. We hope the same fate doesn't befall the Bald Cypress tree, which is one reason we planted--and delight in--the several young specimens that are finally producing cones along the banks of Hilton Pond. Comments or questions about this week's installment? NOTE: Be sure to scroll down for an account of all birds banded or recaptured during the week, as well as some other interesting nature notes. "This Week at Hilton Pond" is written & photographed You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use the on-line Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to "This Week at Hilton Pond," just send us an E-mail with SUBSCRIBE in the Subject line. Please be sure to configure your spam filter to accept E-mails from hiltonpond.org. |

|

Make direct donations on-line through

Network for Good: |

|

|

LIKE TO SHOP ON-LINE?

Donate a portion of your purchase price from 500 top on-line stores via iGive: |

|

|

Use your PayPal account to make direct donations:

|

|

Some dendrologists (tree specialists) claim that inland Bald Cypress trees belong to a separate subspecies called Pond Cypress, but others place their bets on DNA work that indicates Bald Cypress and Pond Cypress are one and the same. The two "varieties" have very similar leaves--lacy, pale-green needles illustrated here--and both produce the woody "knees" that are commonly believed to provide oxygen to the tree's roots when they become submerged in swampy conditions (above left), although this function has not been conclusively demonstrated. And, in an unusual attribute for needle-bearing trees, both varieties are deciduous and lose all their tiny leaves each fall--hence the name "Bald" Cypress.

Some dendrologists (tree specialists) claim that inland Bald Cypress trees belong to a separate subspecies called Pond Cypress, but others place their bets on DNA work that indicates Bald Cypress and Pond Cypress are one and the same. The two "varieties" have very similar leaves--lacy, pale-green needles illustrated here--and both produce the woody "knees" that are commonly believed to provide oxygen to the tree's roots when they become submerged in swampy conditions (above left), although this function has not been conclusively demonstrated. And, in an unusual attribute for needle-bearing trees, both varieties are deciduous and lose all their tiny leaves each fall--hence the name "Bald" Cypress.

As is the case with the 15-foot specimens at Hilton Pond Center, many exist because they were planted by property owners familiar with the tree's potential as a landscape plant. Although many of these trees produce fruit, there is very little dissemination of Bald Cypress seeds in the Piedmont that would keep natural stands healthy and expanding--and that brings up a another sad but fascinating story.

As is the case with the 15-foot specimens at Hilton Pond Center, many exist because they were planted by property owners familiar with the tree's potential as a landscape plant. Although many of these trees produce fruit, there is very little dissemination of Bald Cypress seeds in the Piedmont that would keep natural stands healthy and expanding--and that brings up a another sad but fascinating story.

so to protect their livelihood farmers systematically destroyed local congregations of Carolina Parakeets. A sizable number of individuals also were captured as cage-birds or killed for feathers to adorn ladies' hats. Even Honeybees--those non-native insects brought by early settlers--played a role by displacing parakeet pairs from large tree hollows they needed for nesting! By the mid-1850's, John James Audubon already was reporting an alarming decline in parakeet numbers, and in 1900 there weren't any free-flying flocks big enough to maintain the species. When the last Carolina Parakeet died on 21 February 1918 in the Cincinnati Zoo, no birds remained to disseminate Bald Cypress seeds beyond the local swamp. (Ironically, the last living Passenger Pigeon died four years earlier in the very same zoo.)

so to protect their livelihood farmers systematically destroyed local congregations of Carolina Parakeets. A sizable number of individuals also were captured as cage-birds or killed for feathers to adorn ladies' hats. Even Honeybees--those non-native insects brought by early settlers--played a role by displacing parakeet pairs from large tree hollows they needed for nesting! By the mid-1850's, John James Audubon already was reporting an alarming decline in parakeet numbers, and in 1900 there weren't any free-flying flocks big enough to maintain the species. When the last Carolina Parakeet died on 21 February 1918 in the Cincinnati Zoo, no birds remained to disseminate Bald Cypress seeds beyond the local swamp. (Ironically, the last living Passenger Pigeon died four years earlier in the very same zoo.)