|

|

|||

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

A SOUTHERN NORTHERN

SAW-WHET OWL Owls are both mystical and mythical. Most people know little about them, primarily because we are diurnal and owls are creatures of the night. Our human eyes are far less light-sensitive than those of owls so we seldom venture out after sunset to explore the darkness. When folks do sally forth, their typical owl encounters are audible rather than visual: The deep hoot of a male Great Horned Owl or the inquisitive duet of "Who Cooks For You, Who Cooks For You All" performed by a nesting pair of Barred Owls--which occasionally are seen patrolling their territory at dusk before the lights go out.

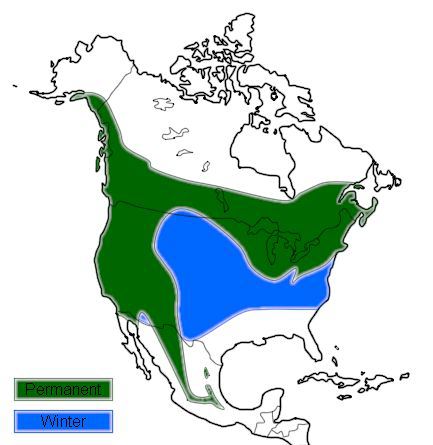

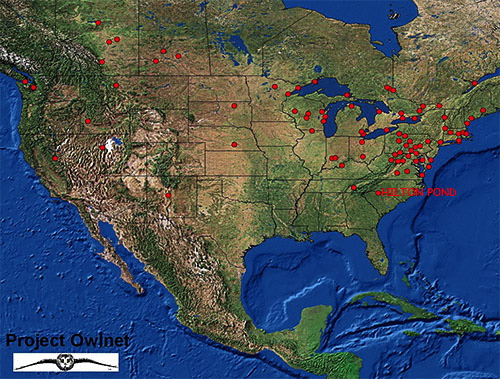

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The name "Northern Saw-whet Owl" is entirely appropriate for this smallest owl in eastern North America. "Saw-whet" comes from its call, a repetitive "toot-toot-toot . . ." reminiscent of the sound made by sharpening, or whetting, a hand saw. The adjective "Northern" is equally apt, for this owl breeds across boreal Canada, New England, the northwestern U.S., and down the Rockies at high altitudes into Mexico. So if its typical range is so far north, how can we refer to the southern Northern Saw-whet Owl (above) as the smallest owl at Hilton Pond Center? More than a decade ago various researchers in the northern U.S. began looking more closely at fall incursions of Northern Saw-whet Owls. Some winters NSWO remained on their nesting grounds (green on map at left), but other years saw massive movements within and beyond the breeding range (typical winter range extension is in blue). To better understand migration and population trends of saw-whets and other North American owls, a U.S-Canadian network called Project Owlnet was established by owl banders (and other insomniacs). Because Northern Saw-whet Owls held particular interest, Project Owlnet developed saw-whet capture protocols that involved deploying mist nets during migration. Just putting up nets at night would provide few chances of actually catching owls, so the banders tried to attract NSWO into the nets with a decoy: A continuous playback recording of the saw-whet's "toot-toot-toot . . ." call. This audiolure, broadcast at rather high volume as owls flew over a banding site, brought NSWO close to the sound source that--surrounded by nets--led to their capture. Some owl study sites in Pennsylvania, Maryland, Wisconsin, and elsewhere were phenomenally successful, using dozens of volunteers to capture hundreds of NSWO each autumn.

We were intrigued by the success of northerly banders and wondered if any Northern Saw-whet Owls ever came as far south as Hilton Pond Center. It seemed unlikely--saw-whets are rarely observed in the Carolinas and then mostly in the mountains--but that merely piqued our curiosity further. We inquired at the Bird Banding Laboratory in Laurel MD and learned that through October 1999 only four NSWO had ever been banded in the Palmetto State--the first in 1960 and the last in 1972, all in the Coastal Plain; none had ever been banded in South Carolina's Piedmont region where the Center lies. Undeterred and challenged by this news, in the fall of 1999 we registered Hilton Pond as the southernmost Project Owlnet study site (see map above) and laid plans to capture saw-whets.

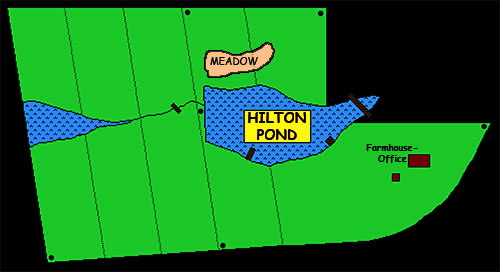

We selected a small meadow north of the pond (above) in which to erect a triangle of 60mm-mesh mist nets that are 42 feet long by eight feet tall; we also extended a fourth net from one of the triangle apices. Then we ran 400 feet of extension cord from the Center's old farmhouse and office--the closest electrical source--to the middle of the net triangle. There we placed a boom box with a continuous-loop tape of the NSWO call: 30 seconds of toots followed by 15 seconds of silence. Our first attempt at capturing southern Northern Saw-whet Owls at Hilton Pond Center came beginning at 6 p.m. on 28 November 1999. After dark we unfurled our four nets, turned on the audiolure, and retreated from the meadow to await arrival of our first NSWO. Even from a hundred yards away we could hear the monotonous "toot-toot-toot . . ." of the tape, so we felt sure any NSWO in the vicinity would fly in to investigate. After 30 minutes we returned to the meadow to find nothing but empty nets. Results were the same every half hour until 3 a.m. when we decided to call it quits, turned off the boom box, and closed the nets. That night ended up being a lot of toots and net checks yielding no return on our investment. In our sleep-deprived fuzziness we thought maybe this southern Northern Saw-whet Owl project wasn't going to work after all. The next night we tried again, opening nets at 6 p.m. and making checks at 30 minute intervals. At 7 p.m.--no birds; 7:30 p.m.--the same, and again nothing at 8, 8:30, 9, 9:30, and 10 p.m. Needless to say, we were getting tired of toots and empty nets and were about to give up again. At the 10:30 p.m. visit, however, we walked toward the meadow and in the light of our head lamp could see one of the metal net poles swaying slowly back and forth. There was no wind, so our pulse quickened as we realized there might be something in the net causing to pole to move. We were ecstatic over these two captures on the night of 29 November 1999--our first-ever NSWO caught at Hilton Pond Center or in the South Carolina Piedmont--and only the fifth and sixth ever banded in the whole state. Flush with success, we ran the audiolure again on 30 November and caught TWO MORE saw-whets at the 9 p.m. check. The next evening brought no new NSWO, but we caught one each night on 2, 5 and 8 December to bring our total to SEVEN. Obviously, the audiolure used so productively by our colleagues in Maryland and Wisconsin really COULD be used to attract southerly saw-whets for banding, but only because the elusive, unseen northern owls were here in the first place. After our seven saw-whet bandings in November and early December, 13 additional nights of playing the audiolure in mid- and late-December 1999 and early January 2000 failed to bring in any more Northern Saw-whet Owls to Hilton Pond Center. It may be we had caught all the saw-whets wintering within hearing range of the boom box, or that by January the winter residents already had begun moving back north. In any case, we HAD caught seven NSWO in our first winter of trying, surprising quite a few folks who thought there weren't ANY in the Carolina Piedmont. In Year Two (2000) we started playing the audiolure a month earlier (31 October) to try to determine when NSWO might actually begin to arrive in the Piedmont. We ran nets for several nights and then took a break, finally capturing a saw-whet on 30 November--a year and one day after the first local bandings for this species. (HISTORICAL NOTE: At right is John James Audubon's rendering of two NSWO, the lower one grasping a Deer Mouse. Audubon referred to this bird as the "Acadian Owl" because Europeans first discovered the species in Acadia--now Nova Scotia. The scientific name Aegolius acadicus reflects this history, with the generic epithet coming from a Greek word for "owl." In Quebec the little saw-whet is called la petite nyctale.) Although we wanted to continue our Hilton Pond saw-whet project after our surprising successes from 1999 to 2001, eye and knee surgeries and illness interfered in 2002-2003 and 2005-2006, and three nights of work in early December 2004 produced no owls. That brings us to the present (December 2007), when we were determined to try once more--especially after learning a bander had captured a saw-whet in north Georgia in November this year. Three weeks ago we prepared the Hilton Pond meadow for another round of owl-netting. This involved judicious trimming of Eastern Red Cedar trees whose branches had grown into the net lanes. With customary optimism, we opened mist nets and cranked up the audiolure at 7 p.m. on 5 December 2007--a somewhat later start date than in previous years but the anniversary of the capture date of our sixth NSWO back in 1999. As usual we checked the nets every 30 minutes through the night, catching nothing through 2 a.m. (Did we mention trying to catch owls is exhausting and sleep-depriving and even uncomfortable on cold nights?) On the 2:30 a.m. check, ever hopeful, we strolled into the meadow and aimed our spotlight at each net. Seeing nothing, we sighed deeply and started to walk out when a light-colored bird with two-foot wingspan silently glided overhead and into the trees surrounding the meadow. Although we couldn't be positive, we believed it to be a Northern Saw-whet Owl and quickly but quietly retreated in the hope it would return. Alas, our next three half-hour checks revealed nothing in the nets, so at 4 a.m. we shut down the operation to try for a few hours of shut-eye before tackling our usual daytime tasks.

Travel and other obligations interfered with owl-catching attempts for the next week or so, but on the night of 14 December 2007 we took time to unfurl nets and start the audiolure at 7 p.m. Even though we'd never caught a NSWO so far into December--our late date was 8 December 1999--we just had a feeling there were saw-whets out there somewhere. The usual half-hour checks produced nothing through 2 a.m., but a half-hour later we entered the meadow, made a sweep with our spotlight, and saw a suspicious ball of feathers in one of the nets. Up-close it turned out to be a Northern Saw-whet Owl (above), our first since 2001 and the tenth captured at Hilton Pond Center.

We quickly extricated the owl from the net, noticing its well-insulated little body was quite a bit warmer than our chilly fingers--shown above to give a sense of scale for the size of a saw-whet. After removal we placed the bird in a soft mesh bag for transport back to the old farmhouse. Saw-whets often are quite passive, but this feisty individual tried several times to snag us through the mesh with sharply decurved talons quite capable of puncturing human skin. It only drew blood once. (ANATOMICAL NOTE: The photo below left is of our latest NSWO's left foot. Note the outer toe swivels and can point either forward for perching or backward for a more secure grasp on prey-- Back at the banding table we could examine the new saw-whet closely, make measurements, and figure out its age and sex. First we put the bagged owl on an electronic scale; after subtracting bag weight we found the owl alone weighed 97.4g--about 3.4 ounces. We also used a metric rule to find the saw-whet's wing chord, the distance from a bird's wrist to the tip of its longest primary feather; it was 142mm--longer by 5 mm than any of the previous nine NSWO banded at Hilton Pond. Although Saw-whets are sexually monomorphic--males and females look alike externally--Dave Brinker and other banders on saw-whet breeding grounds have learned male NSWO are smaller, with wing chords of 124-140mm; females have wing chords of 130-148mm, so our bird fell in the middle of the range for females. The new saw-whet's 97.4g weight was a second clue to its sex: Males weigh 70-84g while females range from 88g to a whopping 165g, confirming that our 2007 capture was indeed female.

Banders can determine the general age of an in-hand saw-whet in one of two ways. The first involves simply looking at the primary and secondary plumage--the long flight feathers on the wing. If they are all similar in color and wear it's the sign of a young bird. The feathers are uniform in the above photo of the NSWO we captured this week, meaning she must have hatched out and fledged in Spring 2007.

In contrast, a NSWO with primaries and/or secondaries exhibiting different shades of brown is an older bird that hatched in a previous year. In the photo above the outermost primaries on the right are a tad darker, as are several secondary feathers and some of the coverts covering their bases. Older feathers are faded and more worn on this NSWO that was a probable second- or third-year bird when we caught it in 1999.

The other way to determine age is more fascinating and involves spreading the owl's wing while examining its ventral surface under a black light (above). Curiously, porphyrins--iron-based pigments produced by the owl's liver and laid down in its feathers--fluoresce under ultraviolet light and glow pink. Porphyrins are relatively unstable and decompose over time--sometimes rather quickly on exposure to sunlight--reducing their pinkish intensity. Our 2007 saw-whet, whose left underwing is in the photo above, shows the same pinkishness in ALL its feathers--further evidence she is a young bird of the year. (Note that the pink is uniform in the flight feathers, all of which grew in at the same time when the owlet was in the nest.) A NSWO with feathers having varying amounts of pink is an older bird with different generations of feathers; older feathers show less fluoresence because the porphyrins have faded to a greater degree. Incidentally, at least a dozen orders of birds--not just owls--exhibit glowing porphyrins, some of which may be copper-based. In addition to ageing and sexing our 2007 saw-whet via black light and wing chord, we measured the tail (73mm) and the distance from the tip of the upper bill to the front of the nostril opening (11mm)--a standard way to determine bill length. (REPRODUCTIVE NOTE: Northern Saw-whet Owls are cavity nesters that often occupy abandoned woodpeckers holes--especially those of Northern Flickers. They also use artificial nest boxes erected for them, Eastern Screech-Owl, or Wood Ducks. A female NSWO lays 4-7 white, nearly spherical eggs that take up to four weeks to hatch. Incubation begins when the first egg is laid so the hatch is asynchronous, resulting in young of various sizes in the nest.) We suspect overwintering saw-whets leave the South Carolina Piedmont at latest by mid-March, when they are known to start showing up in good numbers at more northerly migration banding sites. No matter their geographic origin, our midnight mid-winter banding conclusively proves NSWO do occur in the Carolina Piedmont, probably more frequently and in greater numbers than folks might have believed. We're pleased our ten birds banded here at York make Hilton Pond South Carolina's "epicenter" for southern Northern Saw-whet Owls.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

Comments or questions about this week's installment?

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond." (Please see Support if you'd like to make a gift of your own.)

IMPORTANT NOTE: If you ever shop on-line, you may be interested in becoming a member of iGive, through which nearly 700 on-line stores from Barnes & Noble to Lands' End will donate a percentage of your purchase price in support of Hilton Pond Center and Operation RubyThroat. For every new member who signs up and makes an on-line purchase iGive will donate an ADDITIONAL $5 to the Center. Please sign up by going to the iGive Web site; as of this week, 117 members have signed up to help Hilton Pond Center. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our work in conservation, education, and research. "This Week at Hilton Pond" is written & photographed You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use our on-line Hilton Pond Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to |

|

Make direct donations on-line through

Network for Good: |

|

|

LIKE TO SHOP ON-LINE?

Donate a portion of your purchase price from 700+ top on-line stores via iGive: |

|

|

Use your PayPal account

to make direct donations: |

|

| The highly coveted Operation RubyThroat T-shirt --four-color silk-screened--is made of top-quality 100% white cotton--highlights the Operation RubyThroat logo on the front and the project's Web address (www.rubythroat.org) across the back.

Now you can wear this unique shirt AND help support Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project and Hilton Pond Center. Be sure to let us know your mailing address and adult shirt size: Small (suitable for children), Medium, Large, X-Large, or XX-Large. These shirts don't shrink! Price ($21.50) includes U.S. shipping. A major gift of $1,000 gets you two Special Edition T-shirts with "Major Donor" on the sleeve. |

Need a Special Gift just in time for the Holidays? (Or maybe you'd like to make a tax-deductible donation during 2007) If so, why not use our new handy-dandy on-line Google Checkout below to place your secure credit card order or become a Major Donor today? |

|

|

|

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS WEEK: * = New species for 2007 WEEKLY BANDING TOTAL 10 species 99 individuals YEARLY BANDING TOTAL (2007) 66 species 2,020 individuals 26-YEAR BANDING GRAND TOTAL (since 28 June 1982) 124 species 50,103 individuals NOTABLE RECAPTURES THIS WEEK (with original banding date, sex, and current age) American Goldfinch (3) 02/26/06--3rd year female 12/22/06--after 2nd year male 03/05/07--2nd year male Dark-eyed Junco (2) Carolina Chickadee (2) Tufted Titmouse (1) White-throated Sparrow (4) House Finch (1) Carolina Wren (1) Eastern Towhee (1) Mourning Dove (2)

|

OTHER NATURE NOTES OF INTEREST --There was another unusual weather happening on 15 Dec: It rained! And significantly. The trusty old weather gauge at the Center read 1.7" at the end of the all-day and evening precipitation event. This brought the total for past five months to a mere 2". --Although banding totals at left are for a two-week period, we only ran nets and traps for seven of the 14 days due to weather and a family medical crisis. Nonetheless, on 19 Dec we banded our 2,000th bird for 2007 (an American Goldfinch)--the 12th time we have reached that annual milestone in our 26 years of research at Hilton Pond Center. --We made another attempt to lure Northern Saw-whet Owls (see write-up above) on the night of 19-20 December but caught none. Our plan is to repeat the effort several more times during December 2007 and January 2008. For individual descriptions of all ten saw-whets banded to date at Hilton Pond Center, please see RESEARCH: NSWO. That page links to another with info about the other five NSWO banded elsewhere in South Carolina through the years.

|

|

|

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) Up to Top of Page Back to This Week at Hilton Pond Center Current Weather Conditions at Hilton Pond Center |

You can also post questions for The Piedmont Naturalist |

Join the |

Search Engine for |

|

|

Nordstrom Coupons

A third species, the Common Barn Owl (left), sometimes can be found in church steeples or abandoned warehouses even within big cities; the first we ever encountered was perched on a power pole in downtown Rock Hill SC as we embarked on a field trip well before dawn. Seen or heard, these three owls--Great Horned, Barred, and Barn--may be the species most familiar to casual observers in the Carolinas, but if you ask folks to name the smallest owl found at Hilton Pond Center and elsewhere in the region they may remember a fourth: The Eastern Screech-Owl. This species is indeed small, only eight inches tall with a 22-inch wingspan compared to the 20-inch height and 55" span of the Great Horned. But believe it or not, miniscule Piedmont screech-owls are actually BIGGER than one other local species we netted and banded this week on the banks of Hilton Pond. We speak here of the diminutive southern Northern Saw-whet Owl.

A third species, the Common Barn Owl (left), sometimes can be found in church steeples or abandoned warehouses even within big cities; the first we ever encountered was perched on a power pole in downtown Rock Hill SC as we embarked on a field trip well before dawn. Seen or heard, these three owls--Great Horned, Barred, and Barn--may be the species most familiar to casual observers in the Carolinas, but if you ask folks to name the smallest owl found at Hilton Pond Center and elsewhere in the region they may remember a fourth: The Eastern Screech-Owl. This species is indeed small, only eight inches tall with a 22-inch wingspan compared to the 20-inch height and 55" span of the Great Horned. But believe it or not, miniscule Piedmont screech-owls are actually BIGGER than one other local species we netted and banded this week on the banks of Hilton Pond. We speak here of the diminutive southern Northern Saw-whet Owl.

Read on for what we hope you'll find is a fascinating story.

Read on for what we hope you'll find is a fascinating story.

Lo and behold, when we got close enough for our light beam to illuminate the scene, we realized we had not one but TWO light-colored objects in a single net, and both turned out to be Northern Saw-whet Owls!

Lo and behold, when we got close enough for our light beam to illuminate the scene, we realized we had not one but TWO light-colored objects in a single net, and both turned out to be Northern Saw-whet Owls! Six additional nights of netting resulted in no other owls. During Year Three (2001) the first and only capture came on 27 November, just a few days earlier than the earliest local record. This bird brought our total to NINE Northern Saw-whet Owls.

Six additional nights of netting resulted in no other owls. During Year Three (2001) the first and only capture came on 27 November, just a few days earlier than the earliest local record. This bird brought our total to NINE Northern Saw-whet Owls. We also had to repair lower shelves on a couple of nets, mending big holes ripped accidentally by Eastern Cottontails grazing in the meadow. (Since good mist nets cost about $100 each, we always try to repair any that are damaged.) We also had to replace one of the four 100-foot extension cords used to power the boom box because some industrious rodent had chiseled its way through the insulation. (Lucky for THAT animal the cord stayed unplugged when we weren't playing the owl tape.) Our final preparatory tasks for 2007 were to purchase a new boom box and upgrade our sound output by replacing our old tape with a new CD of the "toot-toot-toot . . . " call.

We also had to repair lower shelves on a couple of nets, mending big holes ripped accidentally by Eastern Cottontails grazing in the meadow. (Since good mist nets cost about $100 each, we always try to repair any that are damaged.) We also had to replace one of the four 100-foot extension cords used to power the boom box because some industrious rodent had chiseled its way through the insulation. (Lucky for THAT animal the cord stayed unplugged when we weren't playing the owl tape.) Our final preparatory tasks for 2007 were to purchase a new boom box and upgrade our sound output by replacing our old tape with a new CD of the "toot-toot-toot . . . " call.

which most often is large nocturnal insects such as katydids and moths but can be small songbirds and mice. This reversible toe configuration is known as "semi-zygodactyly.")

which most often is large nocturnal insects such as katydids and moths but can be small songbirds and mice. This reversible toe configuration is known as "semi-zygodactyly.")

We also compared the owl's yellow iris to a standardized color chart and examined its furcular (wishbone) area for fat deposits, of which there were none. After all this we applied size four aluminum band #554-13211 to the bird's heavily feathered right leg (left) and carried her back to the meadow for release. We gently placed the owl on a horizontal branch and stood back for a few minutes before our southern Northern Saw-whet Owl oriented herself and glided off silently into the night. And we do mean silently. Owls are the original stealth flyers and in our limited experience NSWO in particular do not vocalize in migration or on wintering grounds. (CAVEAT: Some reseachers report that non-breeding saw-whets DO vocalize, making sounds other than their typical tooting.)

We also compared the owl's yellow iris to a standardized color chart and examined its furcular (wishbone) area for fat deposits, of which there were none. After all this we applied size four aluminum band #554-13211 to the bird's heavily feathered right leg (left) and carried her back to the meadow for release. We gently placed the owl on a horizontal branch and stood back for a few minutes before our southern Northern Saw-whet Owl oriented herself and glided off silently into the night. And we do mean silently. Owls are the original stealth flyers and in our limited experience NSWO in particular do not vocalize in migration or on wintering grounds. (CAVEAT: Some reseachers report that non-breeding saw-whets DO vocalize, making sounds other than their typical tooting.) Nobody knows for sure, however, because so few of them have been captured, banded, and monitored in the Southeast. (We should point out that saw-whets have been observed in winter as far south as Florida. It's not clear whether southeastern incursions happen annually.) It's entirely possible our ten birds--two-thirds of all the banded saw-whets from South Carolina--didn't come from "up north" at all but are actually part of a population that breeds as far south as the southern Appalachians of North Carolina. Some owl experts believe these more southerly owls actually could be a subspecies different from NSWO of Canada and New England, but more work needs to be done. Saw-whet populations on the Queen Charlotte Island already are placed in a separate subspecies.

Nobody knows for sure, however, because so few of them have been captured, banded, and monitored in the Southeast. (We should point out that saw-whets have been observed in winter as far south as Florida. It's not clear whether southeastern incursions happen annually.) It's entirely possible our ten birds--two-thirds of all the banded saw-whets from South Carolina--didn't come from "up north" at all but are actually part of a population that breeds as far south as the southern Appalachians of North Carolina. Some owl experts believe these more southerly owls actually could be a subspecies different from NSWO of Canada and New England, but more work needs to be done. Saw-whet populations on the Queen Charlotte Island already are placed in a separate subspecies.

Oct 15 to Mar 15:

Oct 15 to Mar 15: