|

|

|||

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

SEVEN "BIRD NOTES"

Even though we're often gone from Hilton Pond Center during May speaking and banding at bird festivals around the country, we're home enough to encounter interesting aspects of bird behavior including nesting and migration. And, because we're fortunate to be able to deploy mist nets on some days in May, we often learn unusual things we wouldn't know otherwise. This week we devote our photo essay to seven "bird notes"--not vocalizations, but snippets of information we've discovered about avifauna in the Carolina Piedmont.

All text, tables & photos © Hilton Pond Center NOTE #1: Polydactyly in a Mourning Dove Perhaps the most scientifically significant happening this week at Hilton Pond Center came near dusk on 19 May. As we prepared to close our mist nets for the evening--we wouldn't want to catch bats, beetles, or White-tailed Deer that come out at night--we saw a large-ish bird fly into a net. We could tell it was a Mourning Dove, Zenaida macroura, a species big enough it usually just bounces out of 25mm or 30mm mesh we use to catch tiny hummingbirds, but this bird settled into loose netting and just sat there. Although the dove flapped a few times as we approached, it was unable to extricate itself, so we went about removing the mesh from its body and appendages. That's when we realized the bird had more toes than usual--five on each foot instead of four--an example of "polydactyly," i.e., "many toes." Mourning Doves normally have just four toes, three in the front and one (the hallux) behind. Our Hilton Pond Mourning Dove had four normal toes on each foot. However, the right foot (top photo) bore what looked like a normal--but extra--hallux, fully formed and with a regular-sized, somewhat blunted claw. The left foot (above right) also had a spare hallux that was smaller with a slightly twisted claw; it was fused at its based with the normal hallux and reminiscent of "syndactyly" that occurs in two of the three front toes of kingfishers. Our Hilton Pond Mourning Dove bearing anomalous digits was an adult male, so indicated by the rosiness of its breast and a pronounced blue wash on its crown. To achieve adulthood this bird must have been able to function more or less optimally despite extra toes that appeared to bend such that the dove could place all of them on the ground in normal fashion. Causes of vertebrate polydactyly are not well understood; Dr. Sakai cites speculation that includes UV-B or nuclear radiation, parasites, and pesticides.

All text, tables & photos © Hilton Pond Center NOTE #2: Hummingbird Shortage, Real or Imagined? As always happens in May, we've gotten quite a few e-mails and phone calls this month about an "apparent shortage" of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, Archilochus colubris, at various reporting stations across the eastern U.S. Most years we remind correspondents and callers of two things: May has been a different story, with days going by without ANY hummers at the feeders, and we have yet to band another ruby-throat since those first two males early last month. This, in our judgment, qualifies as an official "dearth of Hilton Pond hummingbirds."

Like casual observers we have subjective memories of plentiful hummingbirds last fall, but banding also provides us with concrete data we can use to compare hummer abundance from year to year (see table at right). With only two RTHU banded through 21 May, we can declare with confidence (and disappointment) that 2008 is indeed one of our slowest years on record; to be exact, it is the SECOND worst in our 18 complete field seasons since 1985, but not by much. (This is actually our 25th year of banding hummers at Hilton Pond, but we didn't start until July 1985 and were away for significant parts of the season in 1987-89 and 1996-97.) On average over 18 full seasons we banded only about eight RTHU through 21 May--that number being bloated by 1992 AND 1993 when we inexplicably caught a whopping total of 22 birds by that date. Removing those two banner years drops the average to only seven RTHU banded in "early spring." Of our three best years--2004, 2005, and 2007--when we caught more than 200 RTHU--on average we had banded only seven new RTHU by 21 May. Based on these numbers, 2008 is indeed slow, but maybe not as much as it seems. More alarming is the fact this year we have recaptured NO Ruby-throated Hummingbirds banded at Hilton Pond Center in previous years. Normally by 21 May we would have caught as many as ten returning birds, with an 18-year average of five. (See right hand column in table above.) Despite all these stats, we STILL can't explain our especially low numbers of new captures and returns of Hilton Pond Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in 2008. Was it our abnormally cool April and May? Hurricane activity last fall in the Gulf of Mexico? Habitat destruction on wintering grounds in Central America--or in North America? Are hummers feeding on natural food sources right now and ignoring feeders? Is it a one-year blip? Or is it all just part of some natural cycle we don't understand? Whatever the cause we'll have to content ourself with that advice we always give others at this time of year: Be patient, keep the feeders fresh, and see what unfolds as the season progresses. (It may also help if we continue to study hummers for another 25 years or so.)

NOTE #3: Deterring Raccoons from Hummingbird Feeders This discussion of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds brings to mind the seemingly unrelated topic of . . . Raccoons. These little masked bandits have been pilfering sunflower seeds all winter from our platform feeders and traps (Hilton Pond file photo above), but this year they took particular liking to popping fake flowers from our hummingbird feeders and draining all the sugar water. (We've heard from several correspondents they, too, experienced Raccoon raids on their hummer feeders for the first time this year.) It got so bad in late April we had to bring in ALL our hummer feeders each night--no easy task since we maintain at least a dozen year-round to satisfy Ruby-throated Hummingbirds and winter vagrant hummers that rarely wander by. Needless to say, taking down all those feeders at dusk and getting them out before sunrise on a day-to-day basis got pretty old pretty quickly, but any night we failed to bring them in the pesky mammals came back and satisfied their cravings for 4:1 water:sugar cocktails. The evidence was pretty strong Raccoons were the culprits: Missing plastic feeder parts, five-toed paw prints, and lots of what must have been dried 'coon saliva on the feeders themselves. In past years we've resorted to live-trapping our ever-abundant local Raccoons, Procyon lotor, and transporting them to a friend's expansive farm out on the Broad River 15 miles west of Hilton Pond Center. A couple of winters ago we made an amazing 18 trips, but with gas prices so high these days we decided to try something different. One evening this month after bringing in the hummer feeders and spreading them across all available kitchen counter space, we dug up several old feeders that had seen better days. We popped off the yellow fake flowers and added a special "treat" to the faded feeders: The first morning we tried this trick we noticed two feeders had a little slobber on them but the others were untouched, so we repeated our strategy that night. The next morning we saw evidence 'coons had sampled our hot sauce offering at just one station, but for good measure that night we again replaced sugar water feeders with those containing Texas Pete. After three nights in a row of nothing but hot sauce feeders, the fourth night we left the sugar water feeders in place--and have done so every night since. We can't say for sure Texas Pete is deterring the Raccoons, but the evidence is very strong; our hummingbird feeders remain undisturbed by nocturnal raiders. After careful thought, we feel safe in recommending this alternative for others plagued by Raccoons at hummer feeders, with the caveat one must ALWAYS remember to have nothing but sugar water in place by first light when hummers start to forage. The hot sauce probably won't hurt hummingbirds, but it might send them in the same direction as the Raccoons--never to return to your yard. Disclaimer: Our advice does not constitute endorsement for Texas Pete products, nor have we received any compensation from the TW Garner Food Company, based not far from us in Winston-Salem NC--not Texas. (That said, we'd be plum tickled for ol' Pete to support our work!)

NOTE #4: The Melodious Wood Thrush We're not alone in considering the Wood Thrush to have the most haunting and memorable song of any bird in North America. We've heard such sentiments echoed by many folks--even those who aren't birders but have experienced the flute-like call of this Neotropical migrant that breeds at Hilton Pond Center. (The male's song is so ethereal because he is able to sing two notes at once.) Wood Thrushes, Hylocichla mustelina, are in the family of "spot-breasted thrushes" (Turdidae) with three species that only pass through the Carolina Piedmont--Swainson's and Gray-cheeked thrushes and the Veery; a fourth, the Hermit Thrush, occurs locally in winter. Two other thrushes that do breed here are American Robin and Eastern Bluebird. (In these latter two species only juveniles have spotted breasts.)

At the Center we have captured male Wood Thrushes with large cloacal protuberances and females with well-developed brood patches--both indicate local breeding--but we've yet to find an actual nest. Each spring we listen for the Wood Thrush song with some trepidation, knowing the species is under duress due to loss of mature woodland habitat across their eastern North American breeding grounds AND throughout their winter range in the coastal forests of Mexico and Central America. (Brown-headed Cowbirds also play a role in diminishing Wood Thrush nesting success.) Even though Wood Thrush numbers have declined by nearly 50% in most U.S. and Canadian locales, we're very pleased a few of these spot-breasted birds are back at Hilton Pond again in 2008; two banded this spring bring our 27-year banding total for Wood Thrushes to 176, our best banding year being 1993 when we captured 27.

All text, tables & photos © Hilton Pond Center NOTE #5: A Calico Summer Tanager Although the Summer Tanager's song is nowhere near as melodious as that of the Wood Thrush, we're always glad to see tanagers as spring arrives. At Hilton Pond Center we get two species--the Scarlet Tanager, Piranga olivacea, in which the adult male has a crimson body and jet black wings and tail--and the Summer Tanager, P. rubra, whose red male has a more orangey tint and whose wing and tail color matches the body. Fledglings for both species are yellow-olive-green, a color maintained by females of any age. As young males mature, they begin to acquire adult plumage; second years males we capture at the Center in spring are a "calico" mix of yellow and red. Like Wood Thrushes, Summer Tanagers migrate to the New World tropics, but venture a little further by entering northern South America. They breed in open wooded areas--particularly oak forests--and winter in similar locales. Historically they have been placed in the Thraupidae (Tanager Family) but may actually belong in the Cardinalidae with birds like our Northern Cardinal. Although they are rather common around Hilton Pond in summer, we've banded only 150 Summer Tanagers since 1982--probably because they tend to forage high up in trees while our eight-foot-tall mist nets are closer to ground level. NOTE #6: African Birder Ian Sinclair

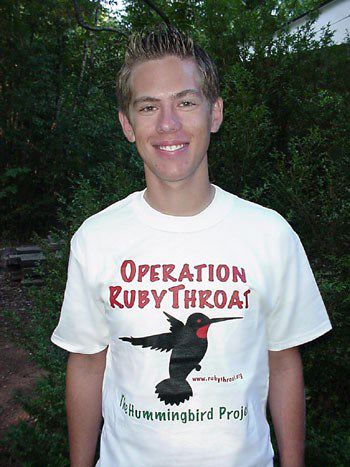

Since the late 1970s Ian has traveled extensively on Madagascar and searched for endemic birds on islands in the western Indian Ocean. For six years he worked at Fitzpatrick Institute of African Ornithology, University of Cape Town, undertaking research projects in the southern oceans and Antarctica. Ian is a prolific writer for both scientific and popular publications. An unabiding interest in birds is reflected in 24 books he has written or co-authored. His field guide Birds of Southern Africa is in its third edition; Upon his return to Cape Town, Ian sent us a photo of himself in the field, decked out in his spiffy new Operation RubyThroat T-shirt (right). THAT should get some attention for the project on his next foray into Madagascar or the Antarctic!

NOTE #7: Faithful Eastern Phoebes

During Ian Sinclair's visit to Hilton Pond Center, we pointed out the active nest of a pair of Eastern Phoebes, Sayornis phoebe, that had built on top of a pillar on the front porch of our old farmhouse. Both Eastern Phoebe parents were very attentive to their brood. The adults spent a lot of time on a shepherd's crook in the front yard (right), perching strategically so they could see insects on the ground and in nearby shrubs and trees. When some nearly invisible movement caught their attention, the adult phoebes would swoop down, gather the prey item, and carry a choice morsel back to the nestlings' gaping mouths. As the adult stuffed food down the gullet of one chick, the nestling beside it would raise its hind end and produce a fecal sac that, in turn, the adult would grab gently with its bill before whisking it away from the nest. Usually the adult phoebe didn't get far before dropping its load, so the concrete floor of our front porch is now dotted with dozens of gleaming white spots consisting of bird . . . guano.

On 20 May the Eastern Phoebe chicks were so large (above) it was impossible for all five to fit in the nest; they practically spilled out while waiting for mom and pop to bring the next meal. Thus, we weren't surprised the next day to find the nest empty, nor to see the short-tailed and somewhat discombobulated fledglings flitting around the yard--still begging for food from what surely must have been an exhausted set of faithful phoebe parents.

So there you have it, seven bird notes made in mid-May at Hilton Pond Center: A multi-toed dove, a couple of Neotropical migrants, the absence of hummingbirds, an anti-raccoon effort, a visit from an esteemed birder, and a successful fledging by birds that made use of human shelter to build their own nest. Ain't nature grand?

All text, tables & photos © Hilton Pond Center

Comments or questions about this week's installment?

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond." (Please see Support if you'd like to make a gift of your own.)

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written & photographed You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use our on-line Hilton Pond Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Make direct donations on-line via

Network for Good: |

|

|

Use your PayPal account

to make direct donations: |

|

|

If you like to shop on-line, you please become a member of iGive, through which more than 700 on-line stores from Barnes & Noble to Lands' End will donate a percentage of your purchase price in support of Hilton Pond Center and Operation RubyThroat. For every new member who signs up and makes an on-line purchase iGive will donate an ADDITIONAL $5 to the Center. Please sign up by going to the iGive Web site; more than 150 members have signed up to help. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our work in conservation, education, and research. |

|

| The highly coveted Operation RubyThroat T-shirt (four-color silk-screened) is made of top-quality 100% white cotton. It highlights the Operation RubyThroat logo on the front and the project's Web address (www.rubythroat.org) across the back.

Now you can wear this unique shirt AND help support Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project and Hilton Pond Center. Be sure to let us know your mailing address and adult shirt size: Small (suitable for children), Medium, Large, X-Large, or XX-Large. These quality shirts don't shrink! Price ($21.50) includes U.S. shipping. A major gift of $1,000 gets you two Special Edition T-shirts with "Major Donor" on the sleeve. |

Need a Special Gift for a Want to make a If so, why not use our new handy-dandy on-line Google Checkout below to place your secure credit card order or become a Major Donor today? |

|

|

|

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS WEEK: * = New species for 2008 WEEKLY BANDING TOTAL 7 species 11 individuals YEARLY BANDING TOTAL (2008) 36 species 872 individuals 27-YEAR BANDING GRAND TOTAL (since 28 June 1982) 124 species 51,039 individuals

|

OTHER NATURE NOTES OF INTEREST --Again during the just-completed week, we were away from Hilton Pond Center for several days to lecture and band at an off-site locale--in this case our third visit to the Mountain Lake Migratory Bird Festival in Giles County, Virginia. We described this annual event back on 15-21 May 2006. That year we banded an adult female Ruby-throated Hummingbird on 17 May and were pleased when we retrapped her in 2007 on 18 May. With our traps set up this year on the lawn at Mountain Lake Hotel, we once again caught this same female--now in at least her fourth year and with thousands of miles on her migration odometer. --Although it was rewarding to recapture that "old" female hummer at Mountain Lake, we were disappointed not to find an active Ruby-throated Hummingbird nest on the same oak tree branch where there had been one both in 2006 and 2007. To add to the disapppointment, the Paper Birch at which a Yellow-bellied Sapsucker had created a hummingbird-attracting "well" was dead--possibly because the sapsucker drilled its trunk with so many feeding holes. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

|

|

|

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) Up to Top of Page Back to This Week at Hilton Pond Center Current Weather Conditions at Hilton Pond Center |

You can also post questions for The Piedmont Naturalist |

Join the |

Search Engine for |

|

|

England Travel

This is known as "anisodactyly"--also the toe configuration of songbirds and many non-passerines. Woodpeckers, by comparison, are "zygodactylous" with two toes fore and two aft. Polydactyly is well-documented in domestic fowl such as chickens, but we found few references in the literature to the phenomenon in wild birds. Most recently, Walter Sakai described a five-toed Vaux's Swift found dead in 2002 near Malibu, California. Dr. Sakai cited records of ten other polydactylous wild birds--all non-passerines but none being doves.

This is known as "anisodactyly"--also the toe configuration of songbirds and many non-passerines. Woodpeckers, by comparison, are "zygodactylous" with two toes fore and two aft. Polydactyly is well-documented in domestic fowl such as chickens, but we found few references in the literature to the phenomenon in wild birds. Most recently, Walter Sakai described a five-toed Vaux's Swift found dead in 2002 near Malibu, California. Dr. Sakai cited records of ten other polydactylous wild birds--all non-passerines but none being doves.

1) There is always an apparent rush of hummers in April that tapers off as some ruby-throats continue northward, as local females spend more time incubating and local males defend territories rather than visiting feeders; and, 2) The greatest numbers of RTHU occur in August and early September when adults and the current year's fledglings are ALL frequenting our feeders. Thus, we encourage folks to be patient in spring, keeping their feeders fresh and waiting until later in the summer. This year, however, seems to be different, with documented lower numbers than usual--at least here at Hilton Pond Center. (We should point out observers at some other U.S. locales report normal or near-normal spring populations of ruby-throats, but our long-term study reveals some interesting things, as follows.)

1) There is always an apparent rush of hummers in April that tapers off as some ruby-throats continue northward, as local females spend more time incubating and local males defend territories rather than visiting feeders; and, 2) The greatest numbers of RTHU occur in August and early September when adults and the current year's fledglings are ALL frequenting our feeders. Thus, we encourage folks to be patient in spring, keeping their feeders fresh and waiting until later in the summer. This year, however, seems to be different, with documented lower numbers than usual--at least here at Hilton Pond Center. (We should point out observers at some other U.S. locales report normal or near-normal spring populations of ruby-throats, but our long-term study reveals some interesting things, as follows.)

A couple of tablespoons of undiluted Texas Pete hot sauce (left). Then we took these old feeders out and hung them in the Raccoons' favorite spots, setting our alarm clock to be sure we were up early enough to take down the spiked feeders before hummingbirds began to stir.

A couple of tablespoons of undiluted Texas Pete hot sauce (left). Then we took these old feeders out and hung them in the Raccoons' favorite spots, setting our alarm clock to be sure we were up early enough to take down the spiked feeders before hummingbirds began to stir.

The Wood Thrush has a rusty head and back (Hilton Pond file photo above), a short tail, and prominent, nearly circular breast spots that distinguish it from its thrush relatives. Its large dark eye (Hilton Pond file photo at right) easily separates it from the Brown Thrasher, a yellow-eyed, long-tailed species common here year-round. Wood Thrushes arrive at Hilton Pond as early as mid-April when males begin to grace our woods with their mating song. In the words of Henry David Thoreau, "Whenever a man hears [the Wood Thrush] he is young, and Nature is in her spring . . . ."

The Wood Thrush has a rusty head and back (Hilton Pond file photo above), a short tail, and prominent, nearly circular breast spots that distinguish it from its thrush relatives. Its large dark eye (Hilton Pond file photo at right) easily separates it from the Brown Thrasher, a yellow-eyed, long-tailed species common here year-round. Wood Thrushes arrive at Hilton Pond as early as mid-April when males begin to grace our woods with their mating song. In the words of Henry David Thoreau, "Whenever a man hears [the Wood Thrush] he is young, and Nature is in her spring . . . ."

The young male in the photo above had a mostly red body and mostly yellow wings, and only the more recently molted central three pairs of tail feathers were fully red (right).

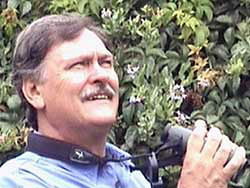

The young male in the photo above had a mostly red body and mostly yellow wings, and only the more recently molted central three pairs of tail feathers were fully red (right). Earlier this month dear friend Peggy Spiegel--an alumna of our second Costa Rica hummingbird banding expedition and organizer of the Mountain Lake Migratory Bird Festival--e-mailed us about banding and lecturing we would do at her 2008 event. Peggy mentioned the other keynote speaker, Dr. Ian Sinclair (left), would be flying into Charlotte NC from his home base in Cape Town, South Africa. Because Hilton Pond Center is less than an hour from the Charlotte airport, we volunteered to meet Ian there, saving Peggy a three-hour drive from her home in Virginia. Ian arrived in the Carolinas in great spirits considering he had been traveling for 32 hours, so we gathered him and his baggage and returned to Hilton Pond for a day of rest before going on to Virginia. Despite jet lag and near-exhaustion, Ian was eager to explore the Piedmont countryside, so we spent quite a bit of time on the Center's trails--where he refreshed his memories of spotting U.S. birds at Cape May NJ 'way back when he was a teenager. Ian's sharp eyes and ears and keen memory did not fail him as he accurately identified species after species he had not seen in person for 30 years or more.

Earlier this month dear friend Peggy Spiegel--an alumna of our second Costa Rica hummingbird banding expedition and organizer of the Mountain Lake Migratory Bird Festival--e-mailed us about banding and lecturing we would do at her 2008 event. Peggy mentioned the other keynote speaker, Dr. Ian Sinclair (left), would be flying into Charlotte NC from his home base in Cape Town, South Africa. Because Hilton Pond Center is less than an hour from the Charlotte airport, we volunteered to meet Ian there, saving Peggy a three-hour drive from her home in Virginia. Ian arrived in the Carolinas in great spirits considering he had been traveling for 32 hours, so we gathered him and his baggage and returned to Hilton Pond for a day of rest before going on to Virginia. Despite jet lag and near-exhaustion, Ian was eager to explore the Piedmont countryside, so we spent quite a bit of time on the Center's trails--where he refreshed his memories of spotting U.S. birds at Cape May NJ 'way back when he was a teenager. Ian's sharp eyes and ears and keen memory did not fail him as he accurately identified species after species he had not seen in person for 30 years or more. A native of Northern Ireland, Ian is considered by many to be the top ornithologist in southern Africa and has led or participated in expeditions across the continent. He made the only known photographs of several African bird species, some thought to be extinct. (We were especially interested in his photo at right of the Lesser Double-collared Sunbird, Cinnyris chalybeus. Although not particularly rare, this iridescent, nectar-eating Old World species fills an ecological niche similar to that of hummingbirds in the Western Hemisphere and, like hummers, even builds its nest from spider webs and lichens.)

A native of Northern Ireland, Ian is considered by many to be the top ornithologist in southern Africa and has led or participated in expeditions across the continent. He made the only known photographs of several African bird species, some thought to be extinct. (We were especially interested in his photo at right of the Lesser Double-collared Sunbird, Cinnyris chalybeus. Although not particularly rare, this iridescent, nectar-eating Old World species fills an ecological niche similar to that of hummingbirds in the Western Hemisphere and, like hummers, even builds its nest from spider webs and lichens.) He visited many islands in the Antarctic where he studied seabird distribution at sea and breeding biology of penguins, albatrosses, and petrels. He was on staff at the Durban Science Museum, was lecturer at the Natal University's Extramural Department during the 1980s, and for years ran his own birding tour company. Ian's sound recordings have been used in research and for sonogram production and have been reproduced in commercial bird tapes and compact discs in Africa and Europe.

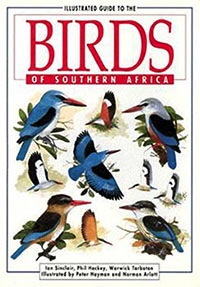

He visited many islands in the Antarctic where he studied seabird distribution at sea and breeding biology of penguins, albatrosses, and petrels. He was on staff at the Durban Science Museum, was lecturer at the Natal University's Extramural Department during the 1980s, and for years ran his own birding tour company. Ian's sound recordings have been used in research and for sonogram production and have been reproduced in commercial bird tapes and compact discs in Africa and Europe. Southern African Birds, A Photographic Guide proved very popular, selling out within a few months. Ian's largest work, A Field Guide to Birds of Sub-Saharan Africa, is touted as the most comprehensive and lavishly illustrated bird guide to any of the world’s continents. We were honored to host Ian Sinclair for a couple of days at Hilton Pond and to receive a personally inscribed copy of his South African guide (above left).

Southern African Birds, A Photographic Guide proved very popular, selling out within a few months. Ian's largest work, A Field Guide to Birds of Sub-Saharan Africa, is touted as the most comprehensive and lavishly illustrated bird guide to any of the world’s continents. We were honored to host Ian Sinclair for a couple of days at Hilton Pond and to receive a personally inscribed copy of his South African guide (above left). Although Phoebes tried to nest there in several previous years, they always abandoned--probably due to frequent disturbance as people went onto and off the porch. This year, however, the female sat tight and produced five chicks in a nest made primarily of fresh green moss harvested from our trails.

Although Phoebes tried to nest there in several previous years, they always abandoned--probably due to frequent disturbance as people went onto and off the porch. This year, however, the female sat tight and produced five chicks in a nest made primarily of fresh green moss harvested from our trails.

Please report your

Please report your