|

|

|||

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

Blue-throated |

Weeks One & Three are full for our annual |

Canivet's |

|

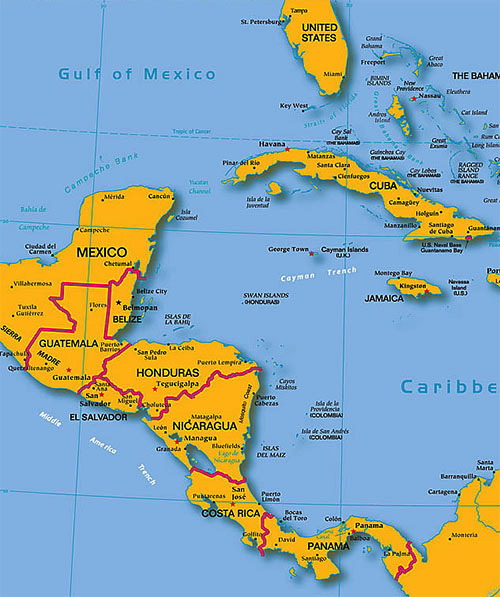

HUMMINGBIRDS IN MESOAMERICA, As described in our previous "This Week at Hilton Pond" photo essay, on 9-15 November 2008 we were in San Salvador to give a paper at the XIIth Congress of the Society for Mesoamerican Biodiversity, attended by more than 600 students and professionals from across Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. Our trip--funded by USAID, SalvaNATURA, and four chapters of North Carolina Audubon--included an introductory hummingbird banding workshop for Mesoamerican biologists at Cerro Verde National Park. At Cerro Verde we were excited to capture two female Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (RTHU) that became the first of their species ever banded in El Salvador. When our week there was over--and since we were already so far south (see map below)--we decided to extend our trip to include seven more days in neighboring Guatemala, another country in which little work and no banding had been done on wintering ruby-throats.

Our Guatemalan connection began a couple of years ago when we inquired through various on-line listservs whether anyone knew of concentrations of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds on their tropical wintering grounds. We were especially looking for folks maintaining feeding stations to attract these migrants because it's often easier to observe and capture RTHU coming to feeders. Despite the extensive variety of hummingbird species in Mexico and Central America, it appears few residents there share North America's obsession with feeding hummers; thus, we got almost no responses to our inquiry. We did eventually hear from Carol Anderson, a retired California lawyer who had moved to the volcano highlands a few hours west of Guatemala City. Carol told us in October 2006 she had a few ruby-throats visiting feeders on the shores of Lake Atitlan (see map below), and we were welcome to come band them--something that wasn't feasible at the time. Carol continued to feed and watch her hummers all winter and reported the last ruby-throat left 1 May 2007; we asked her to let us know if any returned the following autumn.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Carol communicated regularly and informed us her first migrant Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--four adult males--showed up at Lake Atitlan on 11 October 2007. They "simply sat on my feeders," she reported, "exhausted and drinking almost continuously." Her numbers grew, and by 26 October Carol was hosting at least 20 ruby-throats; after that, the local population declined and Carol usually saw only a half-dozen per day until the last female departed 14 May 2008. With this many ruby-throats in one locale, it seemed visiting Guatemala with our portable hummingbird trap might indeed prove productive--especially after Carol told us the ruby-throats had returned "in force" this fall. In fact, an adult male arrived at Lake Atitlan on 30 August 2008--incredibly early for a species that doesn't start leaving North America until the first week in August! On 6 October additional ruby-throats showed up at Carol's and by the 30th she was "inundated" by these little migrants from up north. With all this great news in mind, when Mariamar Gutierrez invited us to the El Salvador biodiversity congress we couldn't resist buying a ticket extension that would take us from San Salvador to Guatemala City. Via e-mail we made plans to rendezvous with Carol Anderson in mid-November at her hummingbird haven on Lake Atitlan.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center After the biodiversity congress concluded, on 15 November we rose early at San Salvador's Real Inter Continental hotel, enjoyed our now-traditional sushi and wasabi breakfast, and took a one-hour cab ride across town to the San Salvador airport. There we boarded a Taca Airlines jet for the 45-minute flight into Guatemala City, about 150 air miles to the northwest. The trip made us glad we always ask for a window seat; otherwise we wouldn't have had the opportunity to look out at spectacular volcanoes (above) that tower over much of the Guatemalan countryside.

As we began our descent into Guatemala City (2006 population of 1.2 million, and growing rapidly), we also observed a dense valley-filling layer of smog--undoubtedly caused by home cooking fires, industrial smokestacks, and hundreds of thousands of buses, cars, and diesel trucks. We were sorry to learn metropolitan smog is one of the biggest impediments to tourism in this otherwise beautiful country. The photo above shows a densely built residential area of concrete houses and apartments along the approach route for Guatemala City's airport. Guatemala is bordered to the north by Mexico, on the northeast by Belize, and to the southeast by El Salvador and Honduras (see top map); most folks are aware of the country's Pacific coastline, but it also has ports on the Caribbean.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center After clearing customs at the Guatemala City airport we were met at the curb with a welcoming sign held by Alfonso, a taxi driver Carol Anderson had dispatched to transport us to Lake Atitlan. Alfonso knew little English but was an excellent driver who easily navigated the nearly three-hour trip that began with a steady one-hour climb from the valley floor in which the city lies. The curvy, up-and-down roads took us through forest, agricultural land, and several small towns inhabitated mainly by Mayans. Finally we came to an overlook (above) from which in the distance we could see Lake Atitlan and volcanos and--in the foreground--Panajachel, largest town on the lake.

Carol was waiting for us at Panajachel and after a quick introduction herded us and our luggage to one of the 12-person boats (above) that took us across the water to San Pedro La Laguna--the small town closest to Carol's residence.

Our tuk tuk took us and our luggage through the cobblestone streets of San Pedro directly to Hotel Villa Cuba--a small, rustic, multi-roomed hostel at which Carol had found us a clean and comfortable room (lower right, above) with bath and expansive view for just $10 per night. This arrangement was quite convenient in that Carol rented a small two-room, one-bath house that belonged to the hotel. Her home and proposed study site--where Carol had been maintaining her hummingbird feeders--was a mere 30 yards below.

By the time we got settled in it was late afternoon, so on our first partial day at San Pedro (15 November) we simply visited with Carol and had a pleasant supper on her front porch that overlooked Lake Atitlan and a wonderful yard (above) filled with blooming Poinsettias, Hibiscus, Papaya, and other hummingbird flowers. That evening we reassembled the portable folding hummingbird trap we had transported in our largest suitcase--hopeful we'd be able to get off to a fast start catching and banding hummingbirds the next morning. Lake Atitlan (satellite photo above) is believed to be at least 1,100 feet deep--easily the deepest lake in Central America. Water began filling the caldera sometime around 84,000 years ago after the Los Chocoyos eruption. During this event the volcano blew its top and forced skyward more than 72 CUBIC MILES miles of earth! (To look at this another way, the District of Columbia covers an area of 68 square miles, so imagine dirt from a one-mile-deep hole that broad being thrust upward at high speeds. It is hard to comprehend an explosion so vast.) None of the volcanos around the lake have erupted in the past 160 years, but the area still has seismic activity. During the night it became apparent Day One (16 November) would offer different weather than what we had experienced the day before on the placid boat ride from Panajachel. Shortly after midnight he wind began gusting at 30-40 mph and even from within the comfort of our room we could tell the temperature was dropping. We were in the tropics but were also at an altitude of 5,100 feet--not quite a mile above sea level but high enough for overnight lows near 50 degrees F. As dawn arrived we could see white caps on Lake Atitlan--not exactly optimum conditions for trapping or mist netting hummingbirds. Nonetheless, we'd come a great distance to work with Carol Anderson's ruby-throats, so we quickly hung and set our portable trap, placed a sugar water feeder inside, and sat back to wait.

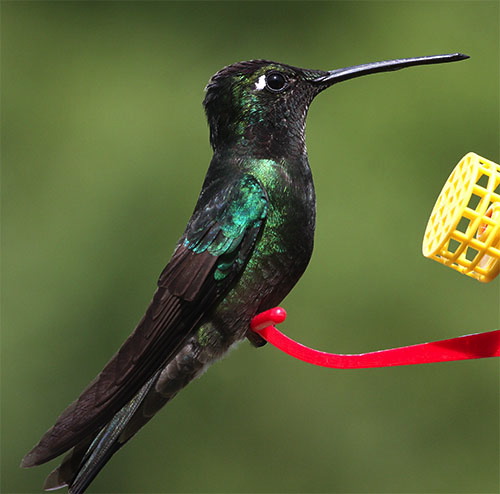

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although it was only a matter of minutes until we spotted our first Guatemalan Ruby-throated Hummingbird at Carol's house, a couple of other species preceded it--both of which we heard before we saw them. Most obvious was the loud buzzing of an iridescent green and black male Magnificent Hummingbird, Eugenes fulgens (above), a relatively huge hummer at least twice the size of a ruby-throat. This was a REALLY big bird and we suspect he tolerated no rivals of his species.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center There were also several somewhat smaller White-eared Hummingbirds, Hylocharis leucotis (above), whose noisy wing flaps had a metallic quality. Both White-eared and Magnificent Hummingbirds are occasionally found in the continental U.S.; the latter even breeds in Arizona and has been seen as a vagrant as far north as Minnesota.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center That first morning we also saw (and later captured) a male Slender Sheartail, Doricha enicura, a hummer with an eye-popping iridescent purple gorget (above). This bird's body was smaller than that of a ruby-throat but its long forked tail (below) extended more than 3" from its body and made it look considerably larger. All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Thanks to the electronic remote we use to trigger our portable trap, we were able to sit comfortably on Carol's porch and watch as various hummingbirds came to lap up sugar water from her feeders. Our only difficulty came from those wind gusts that sprang up overnight and continued throughout the day on 16 November. With feeder and trap swaying in the wind, we had to tie an anchor rope to the bottom of the apparatus to stabilize it and allow birds to enter. After that we figured it was merely a matter of time until a ruby-throat was curious enough to fly in through the open trap door; sure enough, at 7:45 a.m. one finally did. We pushed the button that closed the trap and soon had in our hands what to our knowledge shortly became the very first Ruby-throated Hummingbird ever banded in Guatemala.

This first banded ruby-throat (Y14907) was a female that on subsequent days could be recognized at feeders because she was missing a big tuft of throat feathers (above)--probably from poking her head into something a little too sticky. After the banding and measuring process, we photographed and released this very special ruby-throat and returned to the porch to watch the trap some more.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center In her e-mail communications Carol estimated she had about 15 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds at her feeders this fall, so we were both pleased and surprised when we trapped a new ruby-throat almost every 30 minutes until early afternoon. After that activity slowed considerably--perhaps the hummers were all taking siestas--and we caught no more birds prior to sunset at about 5 p.m. Nonetheless, on our first full field day in Guatemala we were able to trap, band, and release TEN of these tiny migrants that had hatched somewhere in North America and flown to the shores of Lake Atitlan. Day One totals included the following age/sex classes of RTHU, as determinded by plumage condition and molt: Four adult males (above) with full red throats, a hatch year (immature) male with incomplete gorget (below), one obvious hatch year female, an adult female, and three females whose age we could not conclusively determine.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center With such a successful first day we were eager to start again on Day Two (17 November) and asked Carol to rouse us at 5:30 a.m. so we could try for early birds at the feeders. Despite another day of high winds, we caught the first hummer of the day at 6:35 a.m. and were pleased to catch many more--including a late one at 5:22 p.m. Day Two results included an incredible 16 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds but, surprisingly, NO adult males; we caught 10 hatch year males, three adult females, and three hatch year females. Our 26 ruby-throats banded in just two days at Lake Atitlan easily surpassed Carol's original estimate of 15 RTHU and made us feel pretty good about having made the effort to get to Guatemala.

The sun came up on Day Three (18 November) accompanied by a seemingly inevitable stiff breeze and white caps on the lake, but we were on a roll and not to be daunted by mere 40 mph winds. We taught Carol how to operate the electronic release and she did a great job trapping eight new ruby-throats before 10 a.m. She also retrapped three RTHU we had banded on one of the previous two days; later we re-caught six more, which was actually good news because capture/recapture results can help with estimates on the size of local bird populations. Following an early lunch--and after the hummingbirds pretty much abandoned Carol's feeders for the afternoon--we decided to deploy a 30mm mesh mist net (above) donated by Avinet for use with last week's introductory banding workshop in El Salvador.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Despite the wind we almost immediately captured one of several sexually monomorphic Azure-crowned Hummingbirds, Amazilia cyanocephala (above), we'd been watching at Carol's feeders. These multi-colored birds were smaller than the hulking male Magnificent Hummingbird but noticeably larger than ruby-throats. We also netted five more ruby-throats for a Day Three total of 13: one adult male, seven hatch year males, three adult females, and two hatch year females. These new birds gave us a grand total of 39 RTHU banded in just three days.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center On Day Four (19 November)--another windy one--we ran the trap and net again during morning hours and then shut down during the usual midday hummer lull. This allowed for a birding walk that provided us with several "lifer" species, including Red-legged Honeycreeper, Blue-gray Tanager, Bushy-crested Jay, and a Tropical Mockingbird (above) that--except for the pattern of white in its tail--looked quite similar to Northern Mockingbirds we see back at Hilton Pond Center. After the walk we returned to deploy the net and trap again, ending up with 13 more new ruby-throats: four adult males, five hatch year males, three adult females, and one hatch year female; we also had 13 recaptures. This brought our catch for four days to 52 RTHU banded.

One big difference between bander-triggered traps and mist nets is that former are selective; i.e., you only catch what you want. Nets are non-selective, so you're liable to capture anything that flies into one. Such was the case on Lake Atitlan, where we caught six of the Tennesee Warblers feeding on Carol Anderson's big Poinsettia shrubs (above). Our U.S. master permit authorizes us to band any Neotripcal migratory birds we capture, so band the six TEWAs we did--along with an Orchard Oriole, a Black-throated Green Warbler, and an Eastern Wood-Pewee. We also netted several non-migratory birds--including six other hummingbird species--but we released each without a band.

Something really strange happened on Day Five (20 November): We got up before dawn and the wind was NOT blowing! This was the first time since our boat ride on 15 November that we didn't see whitecaps on Lake Atitlan, so we figured it would be a great day for running a mist net that would not be billowing in the breeze. Such conjecture proved unfounded, although we did net four new ruby-throats and trap two: No adult males, two hatch year males, an adult female, two hatch year females, and one unknown-age female, bringing our total to 58. (We also had nine recaptures.) We're certain the local Mayan fishermen were happy Day Five was calm; paddling and standing up in those tiny boats (above) seemed next to impossible when the lake was rough.

Day Six (21 November)--our last day of Guatemalan field work--was just as calm as the day preceding but despite running the net and trap most of the day we caught NO new ruby-throats and had just ONE recapture. We speculated on windy days the hummers had more trouble capturing tiny insects and therefore visited the feeders more often, enhancing the possibility they would be trapped or netted--even when the net moved around in the wind. In the photo above, Carol Anderson adjusts the trap door while a ruby-throat sits and drinks at a feeder in the foreground.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Despite not catching any new ruby-throats on our last full day, we managed to finally get telephoto shots of the remaining two species of hummingbirds visiting Carol's feeding station. One was another small hummer with long rectrices--the male Sparkling-tailed Hummingbird, Tilmatura dupontii (above). (This bird was known formerly as Sparkling-tailed Woodstar, Philodice dupontii.) The seventh and final trochilid at Carol's place was a Blue-tailed Hummingbird, Amazilia cyanura (below), sometimes listed as Saucerottia cyanura. (You may conclude corrrectly that hummingbird taxonomy is in flux, with recent DNA studies revealing some species ornithologists once thought were related really aren't.) This green-bodied, red-billed, Blue-tailed Hummingbird came to feeders only a few times per day but actually entered the trap upon occasion; because he visited so rarely, Carol asked we not try to capture him. It would be interesting to know how far this elusive individual was flying for his little hits of sugar water.

At dusk on Day Six we dismantled and folded the trap, took down the net, and retired to our room for the inevitable task of packing for the trip home. We still took time, however, to review our results, which we found to be remarkable: 58 new Ruby-throated Hummingbirds captured in five days in Guatemala--a country where the species had never been banded before. RESULTS SUMMARY Our 58-bird totals for Lake Atitlan in Guatemala included nine adult males (15.6%), 10 adult females (17.2%), four unknown age females (6.9%), 10 hatch year females (17.2%), and 25 hatch year males (43%). Some of these numbers were remarkably close to what we've banded during the past 24 years at Hilton Pond Center, where young males make up 42.3% of our totals, and adult males 12.1%. Broken down by sex alone there were 34 males (58.6%) and 24 females (41.4%); and by age we caught 19 adults (32.8%), 35 juveniles (60.3%), and four of undetermined age (6.9%). We also had 32 local recaptures involving 21 different birds, some of which were caught more than once.

Another opportunity we had in Guatemala was being able to check molt progress in Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. Interestingly, the vast majority of birds we classified as adults were undergoing wing molt--replacing their primary feathers from the middle of the wing toward the leading edge; conversely, only ONE of the hatch year birds showed wing molt. (In early February on our Costa Rica study site, nearly all ruby-throats have completed or are within 1-2 feathers of completing their 10-primary wing molt.) None of the Guatemalan RTHU exhibited any definite signs of tail molt--except for TWO hatch year males that had black and pointed adult male tail feathers on one side and white and rounded juvenile feathers on the other (above); this unusual condition may have occurred because they lost half their feathers in a conspecific or predator encounter and grew back adult-style replacements. Most juvenile males we captured still had only a few red feathers in their incomplete gorgets, but they had plenty of time to complete that all-important part of their plumage change before returning to North America for the next year's breeding season. Those two young males with non-symmetrical rectrices will also be getting new adult feathers on the side that was juvenile at time of banding.

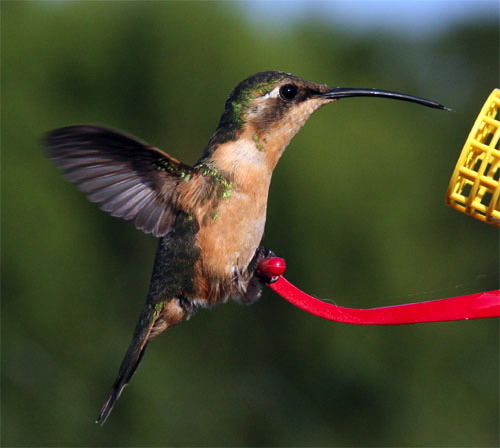

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Because she maintains a bird-friendly yard and faithfully maintains her sugar water feeders, Carol Anderson attracts lots of avifauna--including the migrant female Townsend's Warbler above. (There was some debate whether this bird was actually a female Black-throated Green Warbler--the western U.S. counterpart to the Townsend's--but the face seems too dark. Both species winter in Guatemala.) Carol appears to be hosting one of the densest known winter concentrations of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in the tropics--exceeded only by the 264 individuals we've banded during seven-plus weeks on our study site in Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica. We only only wish more folks in Mesoamerica would get interested in feeding and observing hummers--even if they get non-ruby-throats such as the little female Slender Sheartail (below). If you're aware of on-going hummingbird feeding operations in Mexico or Central America that ARE attracting Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, please send a note to RESEARCH.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Banding 58 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds and recapturing 21 of them at Lake Atitlan suggests we probably caught many (most?) local RTHU during our five days of field work, but there's still much we don't know about what's going on with this species in the Neotropics. Carol's records show ruby-throats get to her place as early as 30 August (although mid-October is more common) and they stay until the first of May (with one female as late as the 14th of that month). Because of the short duration of our time in Guatemala, we don't know whether Carol's ruby-throats spend the whole winter with her . . . OR if in November they're still moving southward toward the southern end of their migratory range in western Panama . . . OR if she gets entirely different birds in spring migration.

We also don't know exactly where Carol Anderson's Ruby-throated Hummingbirds orginated in North America, nor if they show site fidelity at her house as they do on the breeding grounds AND at our winrer study site in Costa Rica. We also have no idea why these birds are along a beach up on Lake Atitlan at 5,100' feet (above), especially when conventional wisdom says Ruby-throated Hummingbirds are more likely at lower elevations in the tropics, and in drier habitats. (Incidentally, we're guessing the two mountain-top ruby-throats we caught in El Salvador and the 58 in Guatemala are the "highest" ruby-throats ever banded--unless someone in the U.S. has handled them atop tall Appalachian ridges.) The success of our work and these resulting questions suggest we need to return to Guatemala next fall to do more work with Ruby-throated Hummingbirds on their wintering grounds.

Thanks largely to Carol Anderson (above, right), science is finally getting a preliminary understanding of ruby-throats in Guatemala, and for this we're sincerely grateful. We deeply appreciate Carol's hospitality and her allowing us to spend a week working with Mesoamerican hummers at her Lake Atitlan locale. Now that we've returned home safely, we can only hope one day next spring we're able to contact Carol with a report that "One of your Ruby-throated Hummingbirds from Guatemala's Lake Atitlan just showed up at Hilton Pond!"

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center GUATEMALA GALLERY Sitting and waiting for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds to enter a trap or fly into a net provides time to take photgraphs of other things. Please scroll down for a gallery of a few of our images from the vicinity of Lake Atitlan, Guatemala. We've divided into sections on People, Places & Things; Plants; and Animals (the latter including a few more looks at hummingbirds). Enjoy! PEOPLE, PLACES & THINGS

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Rising above San Pedro La Laguna is this ridge (above) visible from Carol Anderson's house on Lake Atitlan. Because it resembles the profile of a man lying on his back, it is called La Nariz--"The Nose." Local residents and visitors alike follow the tradition of climbing The Nose and throwing big, loud firecrackers toward town.

San Pedro La Laguna is a backpacking mecca, so despite its relative inaccessibility we often saw foreigners hiking around--sometimes with backpacks as big as they were. The photo above--with The Nose on the horizon and tuk tuks in the middle of the street--depicts the main market area.

Mayan residents of San Pedro La Laguna don't carry backpacks and eschew the ubiquitous tuk tuk. They travel mostly on foot like this woman, even when carrying large items in traditional fashion--on their heads.

On one of the roadside cuts east of San Pedro La Laguna we found this interesting geological situation. The 12-inch-deep gray layer at the bottom of the photo appears to be volcanic ash, while the granular layer just above it was filled with light-weight pebbles. We speculate all this was laid down during the big volcanic eruption that allowed Lake Atitlan to form 84,000 years ago.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Sebastian, the 74-year-old Mayan man above, showed up on the shores of Lake Atitlan almost every morning toting a large hoe with which to rake the beach. He did this to remove sticks and vegetation from sand he then piled up to dry. He told us the sand was destined for use at local construction sites.

A little later in the morning various members of the old man's family would arrive with empty feed sacks, filling them with as much sand as a particular individual could carry. The two young teenagers above were probably hoisting 100 pounds each, using head straps to lessen back strain. The patriarch told us his family got 1.5 quetzales per full bag, with an exchange rate of 7.5 quetzales per U.S. dollar. That's a tough way to earn 20 cents!

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center While providing revenue-generating sand along its banks, Lake Atitlan provides San Pedro La Laguna with its main water supply. It's also a place for bathing and for washing clothes old-style: Pounding them on rocks to get the dirt out.

And here's the entry sign for Lake Atitlan's Hotel Cuba, our home away from home in Guatemala. FLORA Like most places in the tropics, roadsides out from San Pedro La Laguna were covered with flowering plants; as in the U.S., some of the blossoms were native and others invasive. We recognized at least the plant families for most of them, but we'd need to spend more time with Guatemalan botanists to learn scientific names. (If you know the genus and species and/or a common epithet for any unnamed plants pictured in this section, please e-mail it to us at INFO.)

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center This brilliant red flower with long, showy reproductive parts is certainly a hibiscus, but which one? (A common name is Clavel.) We saw it used extensively by hummingbirds and Baltimore Orioles.

We knew for sure the plant on the right--it's Zea mays, or Corn--but the big yellow sunflower on the left we did not. We're guessing it's a Helianthus sp.; we feel obligated to learn its name because it grew vigorously to heights of 12 feet or more on many Guatemalan roadsides.

Here's another member of the Sunflower family, this time one with pinkish-purple ray flowers. Like the yellow one above, it was almost 4" in diameter.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center This inch-wide white flower also appeared to be a sunflower, but maybe not. The Sunflower Family can be very confusing.

And this frizzy white cluster looked to us like like an aster (AKA sunflower) having a bad hair day.

We couldn't even get to the family level with this unusual lavender flower with five petals fused into a nearly flat disk. We wonder if the darker lines on each petal are "bee guides" that direct insects toward nectar (and pollen) at the flower's center.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Papayas, Carica papaya, have two kinds of flowers--male and female--growing on the same individual tree. Male blossoms (above) are thin and tubular and form in big clusters at the end of a long stalk out among the leaf tips.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Female Papaya inflorescence is robust and forms at leaf axils near the tree's center, eventually producting fruit. We've seen Ruby-throated Hummingbirds feeding on Papaya's male flowers in Costa Rica, but aren't sure who uses the female blossoms. (The same species SHOULD feed on both flower types; otherwise pollination wouldn't occur.)

This yellow flower's ID was also a mystery to us, but of one thing we feel certain: The thick, prickly leaves are probably NOT nibbled on by large herbivores with tender lips.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center There was no question about the identification of the ornamental plant with yellow flower stalks at right in the photo above. It's Aloe vera, an African import planted in huge fields in Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica, where its copious nectar load attracts Ruby-throated Hummingbirds on our primary Neotropical study site. GUATEMALA FAUNA Most of the animals we saw around Lake Atitlan were birds, although we did spot a lizard as it scurried into vegetation. On windless days there were tons of butterflies, but a yellow one we were trying to photograph disappeared abruptly into the gape of a Greater Pewee. And then there was that scorpion we found the first night in our room, perched just above the light switch . . . .

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center This White-eared Hummingbird above is aptly named . . .

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center . . . but it could just as easily have been called the Green-headed or Red-billed or Black-cheeked or Emerald-throated hummingbird.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center There's a good size comparison of a White-eared Hummingbird (left) and an immature male Ruby-throated Hummingbird. The latter is

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Great-tailed Grackles--known in Spanish as Zanates--were among

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center If we were a Great-tailed Grackle, we would NOT mess with this particular Magnificent Hummingbird, who looks like he could take on pretty much any potential predator. Carol Anderson likes to call the place on Lake Atitlan "hers," but we suspect the yard REALLY

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We saw only two duck species on all of Lake Atitlan: Four American Wigeon (not pictured) and several flotillas of Lesser Scaup (above). One waterbird note of historical interest: The Giant or Atitlan Grebe, Podilymbus gigas, once endemic to the lake, is now extinct--in part because Black, Smallmouth, and Largemouth bass were introduced as sport fish in the 1950s. These voracious eaters took baby grebes and consumed grebe food such as freshwater crabs, meanwhile eliminating nearly all Atitlan's native fish species.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center One day while walking down the road from San Pedro La Laguna we spotted this Black Vulture in an unknown evergreen tree species. We saw both Black and Turkey vultures around Lake Atitlan; the former always have dark heads, while the latter develops red head skin as it matures.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We mentioned in our main narrative the Tropical Mockingbird (above) has tail markings very different from the Northern Mockingbird we see at Hilton Pond Center. There is much more white in the Tropical species.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Poinsettias at Carol Anderson's house drew not only Tennessee Warblers (as illustrated in the main narrative), but also a few Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (above). The latter seemed to be probing for nectar but could have been after tiny insects.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center There was no question this striking black and red and yellow butterfly (species unknown) was after Poinsettia nectar. It repeatedly uncoiled its long black proboscis and inserted it into individual blossoms. (By the way, on a Poinsettia, the big showy red things are bracts--modified leaves--and are NOT really part of the plant's tiny yellow flowers.)

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center This Ruby-throated Hummingbird had the most complete gorget of any immature male we observed during our week in Guatemala. In coming weeks this individual will replace the rest of its white throat feathers with metallic red ones, the better to attract attention of females up north on the breeding grounds next spring.

All maps, text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our last photo isn't of people or flora or fauna, but of a very nice sunset behind the volcanic hills that surround Lake Atitlan. We hope you enjoyed viewing it and the rest of our photo essay about banding Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in Guatemala. If so, let us know!

Comments or questions about this week's installment?

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond." (Please see Support if you'd like to make a gift of your own.)

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written & photographed You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use our on-line Hilton Pond Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to |

|

Make direct donations on-line via

Network for Good: |

|

|

Use your PayPal account

to make direct donations: |

|

|

If you like to shop on-line please become a member of iGive, through which more than 750 on-line stores from Amazon to Barnes & Noble, L.L. Bean to Lands' End--and even iTunes!--will donate a percentage of your purchase price in support of Hilton Pond Center and Operation RubyThroat. For every new member who signs up and makes an on-line purchase iGive will donate an ADDITIONAL $5 to the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search for the cause! Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site; more than 200 members have signed up to help. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. By the way, if you add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity, it'll be even easier to help Hilton Pond when you shop. |

|

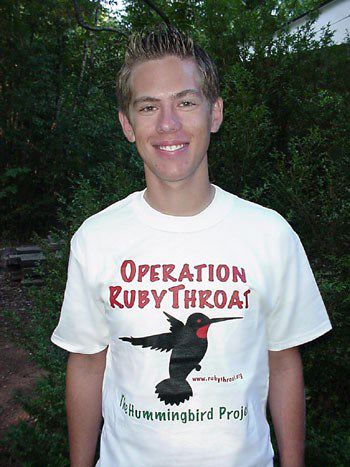

| The highly coveted Operation RubyThroat T-shirt (four-color silk-screened) is made of top-quality 100% white cotton. It highlights the Operation RubyThroat logo on the front and the project's Web address (www.rubythroat.org) across the back.

Now you can wear this unique shirt AND help support Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project and Hilton Pond Center. Be sure to let us know your mailing address and adult shirt size: Small (suitable for children), Medium, Large, X-Large, or XX-Large. These quality shirts don't shrink! Price ($21.50) includes U.S. shipping. A major gift of $1,000 gets you two Special Edition T-shirts with "Major Donor" on the sleeve. |

Need a Special Gift for a Want to make a If so, why not use our new handy-dandy on-line Google Checkout below to place your secure credit card order or become a Major Donor today? |

|

|

|

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS WEEK: * = New species for 2008 WEEKLY BANDING TOTAL 4 species 25 individuals YEARLY BANDING TOTAL (2008) 65 species 1,673 individuals 27-YEAR BANDING GRAND TOTAL (since 28 June 1982) 124 species 51,840 individuals

|

OTHER NATURE NOTES OF INTEREST --Our first waterfowl of the season appeared on Hilton Pond on 28 Nov--two Hooded Mergansers (a drake and a hen). We also banded our first Pine Siskin of the year. --We feel lucky to have been in the tropics for two recent weeks, mostly because the just-completed months was one of the all-time coldest Novembers on record, with low 20s readings for several nights in a row. Brrrrr.

|

|

|

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) Up to Top of Page Back to This Week at Hilton Pond Center Current Weather Conditions at Hilton Pond Center |

You can also post questions for The Piedmont Naturalist |

Join the |

Search Engine for |

|

|

Little Giant Ladders

At 42,000 square miles, Guatemala (flag at right) is seven times larger than El Salvador but is more sparsely settled, with most of the 12.7 million population living in a few major cities. Like El Salvador, Guatemala has considerable agricultural land, but a scarcity of roads allows so many natural areas to remain--especially in the north--the country is considered a "biodiversity hotspot." At 13,845 feet, Tajumulco Volcano is the highest peak in all of Central America.

At 42,000 square miles, Guatemala (flag at right) is seven times larger than El Salvador but is more sparsely settled, with most of the 12.7 million population living in a few major cities. Like El Salvador, Guatemala has considerable agricultural land, but a scarcity of roads allows so many natural areas to remain--especially in the north--the country is considered a "biodiversity hotspot." At 13,845 feet, Tajumulco Volcano is the highest peak in all of Central America.

A sunny, windless day allowed a relatively smooth boat ride to the San Pedro dock where we were met by a man in a tuk tuk (pronounced "tuke tuke")--a sort of three-wheeled motorized rickshaw (or golf cart) with bench seat and canopy. Tuk tuks were everywhere in San Pedro and were the best way to get around unless one wanted to or had to walk. We saw no obese tuk tuk drivers in San Pedro La Laguna, probably because the incessant bouncing of their vehicles on cobblestones--and the town's child-saving speed humps--shook the weight right off.

A sunny, windless day allowed a relatively smooth boat ride to the San Pedro dock where we were met by a man in a tuk tuk (pronounced "tuke tuke")--a sort of three-wheeled motorized rickshaw (or golf cart) with bench seat and canopy. Tuk tuks were everywhere in San Pedro and were the best way to get around unless one wanted to or had to walk. We saw no obese tuk tuk drivers in San Pedro La Laguna, probably because the incessant bouncing of their vehicles on cobblestones--and the town's child-saving speed humps--shook the weight right off.

Oct 15 to Mar 15:

Oct 15 to Mar 15: