|

|

|||

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

|

|

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center CALIFORNIA TRIP (Part 3):

On our first trip to Northern California back in December 2003, our old college roomie Doug Dietz took us to Muir Woods, a 560-acre reserve populated by fine examples of Coast Redwoods, among the TALLEST trees on the planet. When we returned to the West Coast this summer for our tenth triennial Dressler Family Reunion (DFR), we jumped at the chance to visit a much larger stand of these enormous evergreens at Big Basin AND to go on to Yosemite to view some of the world's BROADEST trees--the Giant Sequoias. The DFR was based at Asilomar State Beach on the Monterey Peninsula (Point "A" on the map above), about three hours south of San Francisco.

Reunion attendees took day trips to surrounding areas, including the impressive Monterey Bay Aquarium on Cannery Row. Aquarium exhibits with jellyfish (above) and sea horses (Leafy Sea Dragon, below) were particularly well-done and worthy of many hours of observation. One of the week's true highlights, however, was an hour-and-a-half drive back north past Santa Cruz to Big Basin Redwoods State Park.

Members of the extended Dressler family departed Asilomar on State Highway 1, with scenic views of Monterey Bay periodically obscured by dense fog for which the northern California coast is famous. Turning inland at Santa Cruz, we began a steady upward climb that got us out of the dense fog zone and into clear blue skies and a bright sun that were absent during most of our time at Asilomar.

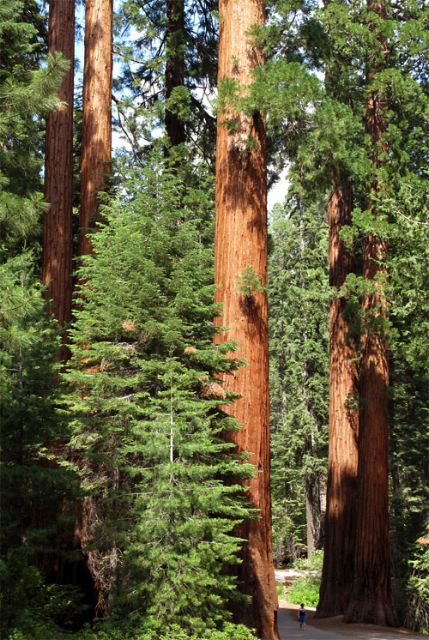

At the picturesque little logging town of Boulder Creek the road steepened and roadside vegetation gave a hint of what lay ahead. The narrow two-lane was lined with old Douglas Firs two to three feet in diameter, plus old Tanoaks and Pacific Madrone trees with many shrubs and ferns and wildflowers growing densely below. And, as we finally turned into the parking lot at Big Basin Redwoods State Park we were met by even bigger trees (above)--Coast Redwoods that shot tall and straight to crowns more than 250 feet above our own five- or six-foot-tall human frames. As we've said before, it's impossible to really comprehend just how tall these trees are without seeing them, so we encourage folks to make a trip westward--if only to ponder the improbable heights of some local vegetation.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center And it's not just that Coast Redwoods are tall; the tallest of them are also quite old. The actual age of trees in the Big Basin stand is driven home in one's mind after stopping at the display of a seven-foot cross-section of a Coast Redwood cut a few decades ago. This exhibit (above) includes several nails driven into the wood at various distances from the section's center. Beside the nails are labels that indicate what was happening in human history at various points in the tree's growth.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We've seen this interpretive technique at other parks, but nowhere did the trees' growth rings reveal such a lengthy existence. In close view we find this particular Coast Redwood had sprouted from seed in about 544 AD when Justinian ruled the Byzantine Empire from Constantinople. Almost three decades after this Coast Redwood began to grow, prophet Muhammad was born in Saudi Arabia--a period in time also marked by Mayan dominance in Central America. Bottom line: When cut this Coast Redwood was nearly 1,500 years old, and it wasn't nearly as ancient as the oldest members of its species!

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We were fascinated by the age and height of towering Coast Redwoods at Big Basin, but we were pleased to see not all of the 16,000-acre state park was populated just by mature trees. In many trailside spots we saw small redwoods less than six feet tall, a sign their older parents were still capable of producing new generations. Indeed, the ability to regenerate themselves is of great importance to mature trees, which obviously have a limited life span and will eventually die and topple to the forest floor. When this happens, seedlings that have been waiting patiently for what we call "a hole in the sky" will rapidly grow toward now-available sunlight, perhaps in two millennia or so to replace their forebears in the canopy.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center It's interesting Coast Redwoods have two distinctly different types of leaves. Saplings--and the lower branches of mature trees--bear needles (above) that are flat, shiny, and elongated, with lots of surface area for photosynthesis and transpiration.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Coast Redwood's canopy limbs, however, produce "shade needles" shorter and more cylindrical (above) and similar to those on an Eastern Red Cedar. Botanists speculate the selective pressure that led to different leaf shapes in very tall trees is simply water availability. Needles close to the substrate have no trouble getting water from a tree's roots--or from ground fog condensation on the needle surface--while leaves 300 feet off the ground in the very treetops are a long way from any water source. Since it's hard for a redwood to supply water to high branches, The Coast Redwood's reproductive devices are surprising inconspicuous for a tree that reaches heights of a hundred yards or more. Pollen comes from tiny, elongated quarter-inch male cones often found on higher branches. Female cones begin as equally small rounded structures scattered along the tips of branchlets. When wind--or gravity--sends pollen into the female cone, the structure matures to an unimpressive half-inch to one-inch knob (above right) with 12-20 scales protecting seeds within. Coast Redwoods can produce cones as early as their fifth year, but less than 1% of seeds from such young trees ever germinate. Redwoods in the 1,200-year range have a similarly low germination rate of about 3%, while maximum viability comes from healthy mature trees about 250 years old. Dissemination occurs when the female cone dries out and the wingless seeds drop to the ground. Coast Redwood seedlings grow far more rapidly than one might expect--18" the first year and up to six FEET per year for the next decade!

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Coast Redwoods sometimes produce gnarly and quite large protrusions known as "burls." The one above in the Big Basin grove was right at ground level and more than six feet long and four feet high. Burls also occur much higher up and sometimes provide a perch on which mosses, ferns, and even wildflowers can grow.

We always thought burls resulted from mechanical injury or pathogens that caused rampant cell divisions yielding tumor-like growth, but some botanists see them as a normal part of redwood physiology. Under a microscope one can see the burl is made of stem tissue. If a burl is placed it water it gives rise to many sprouts that can eventually develop roots, so perhaps the burl is merely a non-sexual way for redwoods to assure survival. In any case, redwood burls are prized by craftspeople and furniture makers who turn them into table tops and bowls with highly distorted but fascinating grain (above).

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Much more common than burls on Coast Redwoods are fire scars. Fire is a natural and extremely important factor in maintaining the health of redwood forests, and the phenomenon also has major impact in individual redwood trees. Historically, small, relatively cool fires probably occurred nearly every year among the redwoods when California's dry season allowed soils and undergrowth to desiccate. If fire occurs regularly, flames merely creep through the undergrowth and knock back the redwood's vegetative competition, but when fire is unduly deterred by misinformed humans lots of dead litter--AKA "kindling"--collects on the forest floor. This creates a potential for major conflagration. (Yes, Smokey the Bear was well-intentioned, but he is what we always refer to as a "quack ecologist.") Even before humans, of course, there were occasional big fires in the redwood forest; some charred the redwood's fibrous bark and--in severe cases--burned through the living cambium layer into the heartwood of the tree. When this happened, fire scars formed. In later years, further fires may have enlarged the fire scar, sometimes making a wound so ominous it's hard to understand how the tree survives. Such is the case in the Coast Redwood above, whose cavernous fire scar went all the way through and easily accommodated 74-inch-tall Billy Hilton III.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center After marveling at and picnicking beneath the old-age trees in Big Basin Redwoods State Park, we awe-struck visitors made our way back to Asilomar. As the Dressler Family Reunion came to a close at week's end, the Hilton wing stayed on in California for a few extra days--in part because we wanted to go on to Yosemite National Park to view the "other" West Coast redwoods--the Giant Sequoias. En route we got a firsthand look at the severity of the Golden State's water problems when we stopped at the San Luis Reservoir in the San Joaquin Valley near Pacheco Pass. Completed in 1967, the reservoir is formed by a packed-earth-and-stone dam--the dark area at left in the photo above, just below the distant mountains; this is the fourth largest embankment dam in the U.S. Although the San Luis Reservoir receives direct rainfall and surface runoff, the bulk of its water is pumped in from the San Joaquin-Sacramento River Delta and released back into the California Aqueduct--primarily for agricultural use. When full, the reservoir is about nine by five miles and covers 12,700 acres, but on the day we visited it was far from overflowing. In fact, although it's hard to get a sense of scale from our photo above, the water level was 168 FEET below full pond! Under normal conditions only the brown crown of the hill in the foreground is exposed, so from its edge to the current water surface is a 168-foot vertical drop. Yes, we'd say California has a water shortage that is bordering on catastrophic, made worse by peculiar, archaic water rights laws that have not been changed in a hundred years.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center With thoughts of the importance of fresh water in mind, we continued on toward Yosemite and again were impressed by the variety and size of roadside vegetation as approached park boundaries. We got into Yosemite without having to pay--serendipitously arriving on a "free day" declared by President Obama to encourage national park visitation--and immediately were struck by the enormity of Giant Sequoias in Yosemite's Mariposa Grove. We've said it before but have to repeat: One can't really understand how big these trees are without seeing them in person. To try to get the point across, however, we direct your attention to our photo above in which a woman is walking down the trail between two sequoias. Keep in mind only about HALF the trees' height shows in the photo! And to drive home our point, in the image below of "Grizzly Giant"--one of the biggest and oldest sequoias in Mariposa Grove--the fat LIMB on the left side of the trunk is nearly seven FEET in diameter!

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Giant Sequoias and Coast Redwoods are cousins, but their taxonomy is somewhat confusing. Originally in the Taxodiaceae (a family mostly consisting of evergreen trees), they've been moved to the Cupressaceae (Cypress Family), a group of coniferous trees and shrubs with worldwide distribution. Our previously mentioned Eastern Red Cedar is in this family, as is Bald Cypress. Family member Dawn Redwood, Metasequoia glyptostroboides--a native of China--joins America's Coast Redwoods and Giant Sequoias as the "redwood triumvirate" of ancient big trees whose lineage goes back 140 million years to the early Cretaceous Period, dominated by dinosaurs. One potentially confusing thing about California redwoods is their scientific names: Coast Redwoods are known as Sequoia sempervirens, while the Giant Sequoia is actually Sequoiadendron giganteum. Giant Sequoias are the largest living organisms, with Yosemite's "General Sherman" tree at 275' in height and a volume of nearly 53,000 cubic feet; this "Methuselah tree" is thought to be more than 2,500 years old. Note that Giant Sequoias aren't as tall as the biggest Coast Redwoods, but many specimens have much greater diameters; General Sherman is 36.5' at his base!

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although it's hard for us to imagine anyone cutting down trees as magnificent as Coast Redwoods and Giant Sequoias, tens of thousands of them were logged over the past 150 years by commercial entities who wanted them for one reason: A redwood is almost impervious to rot. Millions upon millions of board feet of redwood logs were processed in California and shipped around the country for the home building industry. Most redwood logs were sawn into lumber and siding and roofing shingles, while these days it seems redwood goes mainly into making fencing, arbors, and yard furniture. (Pardon us for an editorial note in which we implore our readers NOT to buy redwood products unless they are absolutely sure the wood did NOT come from old age stands. Be aware there are certified redwood forests here and abroad in which new trees are planted for commercial purposes; this is acceptable and no different than landowners who plant Loblolly Pines for newsprint.) At any rate, to drive home just how rot-resistant redwood and sequoia really are we offer our photo (above) of the roots and trunk of "Fallen Monarch," a sequoia believed to have toppled centuries ago.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Compare the first photo of Fallen Monarch, taken this summer, with the 1899 postcard just above. The card shows calvary troops lined up along and atop the huge log more than a hundred years ago. Just above the two front most riders is a gouge in the side of the log; this gouge--and almost all the root network--are almost unchanged in the photo we took 110 years later. Tannins in the log resist decay by fungi and bacteria, and it may be several more centuries until those tannins are leached out by rain and the sequoia's wood becomes a more hospitable home to decomposers.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center As with Coast Redwoods in Big Basin Redwoods State Park, sapling Giant Sequoias--and the lower branches of mature trees--are covered with needles that are broad and flat, while the canopy needles (above) are cylindrical. Again, these so-called "shade needles" have less surface area and lose less water due to transpiration. Sequoias also produce seed-bearing cones (above), but they're much larger--two to three inches in length--and more spherical than one-inch redwood cones.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center As with the Coast Redwoods in Big Basin, many Giant Sequoias in Mariposa Grove bear significant scarring from past fires, both natural and intentional. The sequoia at left above is burned all the way through and even has charcoal marks 40 feet above the ground. Because they are right on the main trail, we suspect these particular trees will never again feel the heat of a big fire, but back in the woods rangers are these days conducting prescribed burns to help return Yosemite to a more natural state. As a result, many more sequoia seedlings are able to sprout--in the hope they will survive a thousand years or so and replace today's giants that eventually will die. Such wise management practices are both refreshing and encouraging.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center This summer's Dressler Family Reunion in northern California was great fun. We liked picnicking among the Coast Redwoods at Big Basin Redwoods State Park, and we enjoyed a tram ride through the Giant Sequoias in the Mariposa Grove of Yosemite National Park. We got to see some astonishing trees, but we want to go back to Yosemite when we can walk the entire loop road and get to know the habitat. We'd like to explore further the relationships between sequoias and Blue Lupine (above) that grows beneath the trees when there's enough light, and we want to crane our necks skyward with a spotting scope to see what birds live 300 feet up in the evergreen canopy. Most of all, however, we'd like to be among the California redwoods and sequoias at dawn before other people arrive. Then, in early morning quiet we'd hug a big red tree, celebrate its longevity, and try to hear if these 2,000-year old conifers have any advice on how we can do a better job making sure they--and we--have a bright and lasting future on Planet Earth. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center POSTSCRIPT #1: Weather during our time among the Coast Redwoods and Giant Sequoias was pleasant, mostly because they were at some altitude. However, it turned out to be 'way warmer as we drove through the San Joachin Valley, where The Fresno Bee (below) reported we were experiencing record-breaking temperatures of 112 degrees--the highest since folks started keeping track back in 1899. Thank heavens for air conditioned rental cars.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center POSTSCRIPT #2 (from John Walters of Bonita CA): "Thought you'd like a little clarification on the function of redwood burls. They are basically dormant buds, not too different from those found in many other plants. The Coast Redwood's preferred habitat is riparian floodplains along short coastal rivers and streams of the California coast. The tree has an extremely wide but very shallow root system. When the stream floods, it deposits a new layer of sediment over the floodplain, so a major flood can deposit several meters of sediment, enough to bury the root system. Burls allow a new shallow layer of roots to sprout in the new sediment, where they are at the proper depth for optimal functioning. Researchers have excavated root systems of redwoods and found traces of multiple root systems layered below current roots, where successive floods have buried the roots and new root systems have sprouted from the burls. These burls can produce new stems above ground, too, if necessary. A very versatile tree." John also says: "One reason Giant Sequoias don't grow as tall as Coast Redwoods is nearly all sequoias reaching more than 200 feet have been struck by lightning; this blasts off the terminal bud and knocks a big chunk from the top of the tree. Sequoias grow at elevations of about 4,000-5,000 feet--the middle of the Sierra Nevada high precipitation zone (rain and snow actually decrease above 7,000-8,000 feet). Thus, Giant Sequoias regularly experience thunderstorms in summer, while Coast Redwoods grow in valleys at elevations mostly below 1,000 feet and experience far less lightning." We also suspect sequoias are affected more by heavy winter snow loads that can break topmost branches and even topple entire trees.

Comments or questions about this week's installment?

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond." (Please see Support if you'd like to make a gift of your own. You can also contribute by ordering an Operation RubyThroat T-shirt.) The following folks made contributions of $25 this month in honor of the 25th anniversary of the first Ruby-throated Hummingbird banded by Bill Hilton Jr. at Hilton Pond Center on 27 July 1984. Please consider joining them via PayPal or Network for Good (below).

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written & photographed You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use our on-line Hilton Pond Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to |

|

Make direct donations on-line via

Network for Good: |

|

|

Use your PayPal account

to make direct donations: |

|

|

If you like to shop on-line, you please become a member of iGive, through which more than 750 on-line stores from Barnes & Noble to Lands' End will donate a percentage of your purchase price in support of Hilton Pond Center and Operation RubyThroat. For every new member who signs up and makes an on-line purchase iGive will donate an ADDITIONAL $5 to the Center. Please sign up by going to the iGive Web site; more than 200 members have signed up to help. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. |

|

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS WEEK: * = New species for 2009 WEEKLY BANDING TOTAL 7 species 26 individuals YEARLY BANDING TOTAL (2009) 37 species 1,141 individuals 28-YEAR BANDING GRAND TOTAL (since 28 June 1982, during which time 170 species have been observed on or over the property) 124 species 52,023 individuals

|

OTHER NATURE NOTES OF INTEREST --A hatch-year male Northern Cardinal netted on 24 Jul was the 53,000th bird banded at Hilton Pond Center since 1982. That's an average of 1,895 birds per calendar year, although the bander wasn't present for significant stretches during a few of those years. --In addition to being the 85th birthday of family matriarch Jackie Hilton, 27 July 2009 was an important day for one other reason: It was the Silver Anniversary of the day we caught and banded our first Ruby-throated Hummingbird, at Hilton Pond Center. Now, 25 years and 5,000 hummingbirds later, we're just beginning to understand these most amazing little birds that have brought us considerable joy and introduced us to new friends in many states and foreign countries. Thanks, hummers!

|

|

|

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) Up to Top of Page Back to This Week at Hilton Pond Center Current Weather Conditions at Hilton Pond Center |

You can also post questions for The Piedmont Naturalist |

Join the |

Search Engine for |

|

|

Kmart Shopping

it's important topmost cylindrical needles have less surface area to lose moisture via evaporation.

it's important topmost cylindrical needles have less surface area to lose moisture via evaporation.

Please report your

Please report your