|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

|

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND 13-21 June 2011 Installment #514---Visitor # (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

COMPOUND LEAVES

As we walk our trails at Hilton Pond Center during most of the year, we're constantly reminded the background color of the Carolina Piedmont is green. In fact, except for polar, desert, and high mountain regions of the world, green is the predominant color of terrestrial habitats. All this green, of course, comes courtesy of vegetation that surrounds us and--more specifically--from chlorophyll that is the lifeblood of diverse flora from lowly mosses to climbing vines to towering trees. Most green plants have leaves (or leaf-like structures) that expose chlorophyll to sunlight and enable the pigment to perform photosynthesis--an elegant chemical process that combines carbon dioxide and water while giving off oxygen and making simple sugars plants use as food. A few plant species can photosynthesize through stems and trunks, but for the most part it is the leaf of the plant that contains chloroplasts. It's interesting to consider that despite their basic similarities, there are almost as many different sizes and shapes of leaves as there are plants--a pretty important concept when students making leaf collections for biology class are basing success on an ability to identify trees solely by leaf configuration.

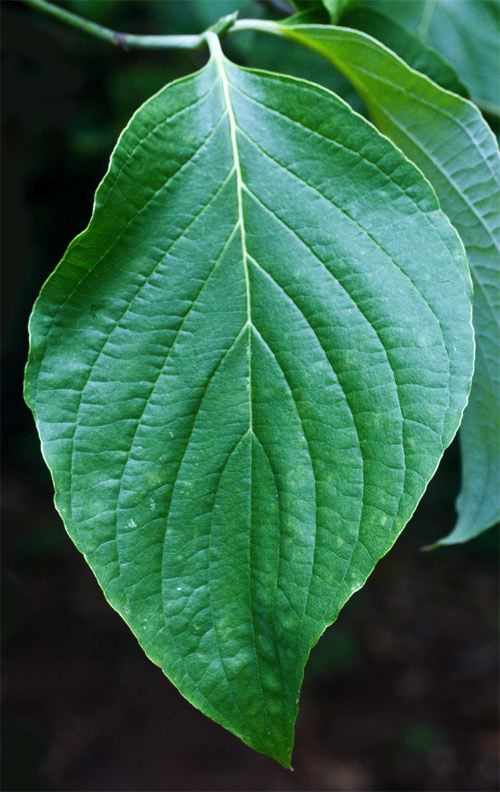

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Despite their diversity, there are two basic leaf types--"simple" and "compound"--and simple leaves can be grouped further into those that are "entire" or more or less "lobed." Foliage of Flowering Dogwood (above left) is a good example of a simple, entire leaf, while that of White Oak (above right) is simple and lobed. Although simple leaves are interesting, we're more fascinated by compound leaves and ways in which they are adaptive for plants that bear them.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center A leaf typically is attached to its stem by a petioles, sometimes known as a "leaf stalk." In a simple leaf, the petiole--variable in length among species--gives rise to the leaf blade; this blade is most often symmetrical and flattened and sticks out on either side of the mid vein, as in the simple, lobed Sweetgum leaf above.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center In compound leaves, however, the blade is dissected into leaflets, so the petiole gives rise to "petiolules" that in turn hold the blades of the leaflets. If we look at the evolutionary history of leaves, it seems likely the first ones were simple and entire and that they sooner or later developed lobes. Eventually, some leaves became so deeply lobed the remaining portions of the blade were separated into what are now leaflets. In a simple, lobed leaf the main central vein has lateral extensions to each side that reach the rest of the blade; in a compound leaf such as Shagbark Hickory (above) the central vein has become a "rachis" and side veins have toughened to become petiolules. These transport water and nutrients to--and sugar from--multiple outlying leaflets. If simple leaves are sufficient for plants that have them, one might wonder how compound leaves would be advantageous. That's something we've pondered quite a bit and have considered a few hypotheses. Most of them boil down to the premise that "there's more than one way to skin a cat"--or, in this case, to capture sunlight for photosynthesis.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center It might seem logical that if a leaf is the main way a plant presents its chlorophyll for photosynthesis, the bigger the leaf the better. A really big blade would have lots of surface area for gas exchange and transpiration of water, and it would be like a big solar panel collecting sunlight. But an over-sized simple leaf also would have disadvantages--especially in areas subject to cold weather. It takes lots of energy to make big leaves, and since most temperate trees are deciduous, that would mean devoting a huge amount of resources to making huge new leaves each spring. For example, at Hilton Pond Center this week we found a fresh new Black Walnut compound leaf (above) that was 19 inches by 9 inches at its longest and widest points. If instead of being dissected into 11 leaflets it had been a simple, entire leaf blade it would have been enormous and would require a major effort to produce. (It's interesting that on our hummingbird expeditions to Central America we've observed many trees and shrubs with giant leaves, perhaps because their foliage is evergreen and doesn't need to be renewed in entirety each year.) We also suspect big simple leaves might provide so much green mass that herbivores would find them irresistible, meaning it might be better to have many smaller leaves--or compound leaves with parts of the blade "missing." And think of what a summer storm would do to a huge but relatively delicate leaf blade when wind gusts got really strong. (In fact, Dr. Steven Vogel tested leaves in wind tunnels and discovered compound leaves typically had much less stressful fluttering and eventual tearing than did simple leaves.)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Perhaps the best rationale for compound leaves comes to mind when we look at a compound-leafed plant from sun's-eye-view. In our photo of a young Winged Sumac shrub (above), we can see its compound leaflets branch off the main trunk not directly beneath each other but from different angles. This means the topmost newer leaves are not directly blocking the sunlight from the older leaves below. And--more important--since the leaves are compound rather than a big, entire blade the amount of shade they cast is diminished even more. Lots of simple leaves branching alternately from a central trunk might have the same effect, so compound leaves are likely just a different way of solving the shading problem. Although it seems the majority of plants have simple leaf configurations, it's surprising how many examples of compound leaves can be found when one starts looking. Below is a sampling of compound-leaved flora we photographed with little effort at Hilton Pond Center, and there were quite a few more specimens for which we didn't use our camera. How many examples of compound leaves can you find in your own backyard? PORTFOLIO OF COMPOUND LEAVES

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center In plants with "palmately compound" leaves the leaflets radiate from the end of the petiole, creating a hand-like configuration. One example of this is five-leaflet Virginia Creeper (above). Many folks confuse this native vine with Poison Ivy, which has only three leaflets.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center "Pinnately compound" leaves exhibit wide variety, but in all the leaflets are arranged along the mid-vein. A few are "even pinnate" without a terminal leaflet, while most are "odd pinnate" and bear a leaflet at the end of the rachis--as in the native Trumpet Creeper vine (above).

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Leaflets on some pinnate leaves are further dissected into sub-leaflets and are referred to as "bipinnately compound." Included in this category is the non-native Mimosa tree (above) that--although invasive--has eye-pleasing foliage.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Compound leaves are not limited to the higher flowering plants (angiosperms). In fact, the vast majority of ferns appear to have pinnate or bipinnate fronds, as in Ebony Spleenwort (above). In some ferns the leaflets are not entirely free of the midrib--especially at the tip of the frond--so it has been argued they actually have simple leaves with deeply lobed blades. (As one might expect, botanists have a word for this: "Pinnatifid.")

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Along these lines, at Hilton Pond Center we have patches of Winged Sumac (above), so-named because of narrow sections of blade that remain along the mid-rib between leaflets. Other native sumacs such as Staghorn and Shining Sumac do not sport these tiny wings.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center When out looking for compound leaves, be careful not to confuse them with plants that actually have opposite, simple leaves--as does Chinese Privet (above). Each of its leaves is attached to the stem with a petiole, so it's not a compound situation.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center In Red Clover (above), the leaf is pinnate but there are only three leaflets. This is referred to as being "trifoliate" and is expressed in clover's scientific name, Trifolium spp.

Non-native Multiflora Rose (above) has leaves that are pinnately compound and leaflets that are sharply serrated. Fortunately, the edges of the leaflets are sharp like the plant's decurved prickles--which most folks mistakenly call "thorns." Happy Compound Leaf Hunting! |

The Piedmont Naturalist, Volume 1 (1986)--long out-of-print--has been re-published by author Bill Hilton Jr. as an e-Book downloadable to read on your iPad, iPhone, Nook, Kindle, or desktop computer. Click on the image at left for information about ordering. All proceeds benefit education, research, and conservation work of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. The Piedmont Naturalist, Volume 1 (1986)--long out-of-print--has been re-published by author Bill Hilton Jr. as an e-Book downloadable to read on your iPad, iPhone, Nook, Kindle, or desktop computer. Click on the image at left for information about ordering. All proceeds benefit education, research, and conservation work of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. |

|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

If you Twitter, please refer

"This Week at Hilton Pond" to followers by clicking on this button: Tweet Follow us on Twitter: @hiltonpond |

Comments or questions about this week's installment? Send an E-mail to INFO. (Be sure to scroll down for a tally of birds banded/recaptured during the period, plus other nature notes.) |

|

--SEARCH OUR SITE-- For a free on-line subscription to "This Week at Hilton Pond," send us an |

|

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond." Please see Support if you'd like to make a gift of your own.

|

|

Make credit card donations

on-line via Network for Good: |

|

|

Use your PayPal account

to make direct donations: |

|

|

If you like shopping on-line please become a member of iGive, through which 800+ on-line stores from Amazon to Lands' End and even iTunes donate a percentage of your purchase price to support Hilton Pond Center .

Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause! Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause! Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. |

|

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS WEEK: * = New species for 2011 WEEKLY BANDING TOTAL 6 species 30 individuals 2011 BANDING TOTAL 24 species 1,517 individuals 5 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds 30-YEAR BANDING GRAND TOTAL (since 28 June 1982, during which time 170 species have been observed on or over the property) 125 species (30-yr avg = 66.9) 56,394 individuals (30-yr avg = 1,880) NOTABLE RECAPTURES THIS WEEK (with original banding date, sex, and current age): Carolina Wren (1) 07/30/09--3rd year female

--We've been told by numerous Web site visitors it's perfectly acceptable if we occasionally include photos of new granddaughter McKinley Ballard Hilton on these pages. The six-week sleepytime photo above was taken by her father, Billy Hilton III. |

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center OTHER NATURE NOTES: --NEXT week on 28 Jun we will celebrate the 29th Anniversary of our first bird banded at Hilton Pond Center and then will begin our 30th year of on-site research. Seems like 1982 was just yesterday. |

...

...

Please report your

Please report your