|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

|

|

|

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center COSTA RICAN HUMMINGBIRDS In early November we departed Hilton Pond Center for two weeks in Costa Rica, where since 2004 we've been conducting the only long-term systematic studies of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (RTHU) on their Neotropical wintering grounds. Until this year, our Operation RubyThroat expeditions had been to Guanacaste Province on the country's Pacific Coast, where RTHU from North America concentrate in expansive Aloe Vera plantations and partake of non-native aloe's copious nectar (above). That area around Liberia and Cañas Dulces--discovered almost ten years ago by our tico guide and colleague Ernesto Carman Jr.--has been quite productive (762 ruby-throats banded at several different study sites) and we have yet another citizen science trip to Liberia coming up in February. (Limited space is still available; see Costa Rica East 2012.)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center A year or so ago, 'Nesto documented another winter population of RTHU in commercial fields of Chayote, a squash grown on horizontal trellises (above) in the river valley at Ujarrás on Costa Rica's Caribbean slope. These birds were gathering in part of the country where RTHU historically have been reported only a few times each year. 'Nesto noticed RTHU numbers at Ujarrás didn't seem nearly as high as over in Guanacaste, but still we couldn't resist the opportunity to mount an expedition to band and observe Ruby-throated Hummingbirds where "they're not supposed to be."

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although we did find Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in the Chayote fields at Ujarrás--and observed far more than the 44 we banded--the most common hummer species by far was Rufous-tailed Hummingbird, Amazilia tzacatl (above). These aggressive, nearly ubiquitous, medium-sized (4") hummingbirds were constantly hitting our mist nets, so beginning Day One after we held a rufous-taled for examination by the group we instructed everyone to carefully dump them out of the nets and wait for something else.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Rufous-tailed Hummingbirds are accurately named, with bright rusty rectrices (above) they fan and flash at conspecifics when defending territories. They have stout wings and what our volunteers considered to be cantankerous dispositions; seldom did a rufous-tail sit quietly in a mist net after capture.

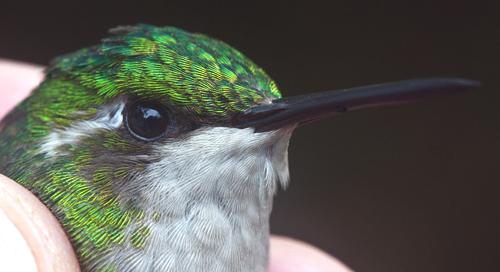

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Rufous-tailed Hummingbirds are sexually monomorphic, with males and females looking alike externally. Both sexes have iridescent green heads and bodies and slightly decurved bills with some degree of red. With a range that stretches from Central Mexico through northern South America--and with an apparently ability to co-exist with human development--this species is probably one of the more common of the world's hummingbirds.

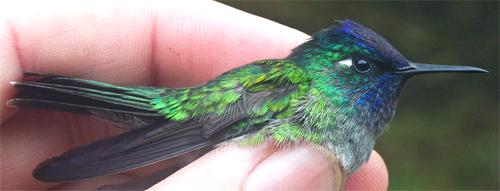

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Only slightly less frequently mist netted than rufous-tails were Steely-vented Hummingbirds, Amazilia saucerrottei, which take their common name from the gun-metal color of their undertail coverts (above). The tail itself is even brighter blue.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Head-on (above)--with its iridescent green head and gorget--the Steely-vented Hummingbird superficially resembles its congeneric Rufous-tailed Hummingbird, but the former has a straight, black, somewhat short bill while that of the rufous-tailed is decurved and reddish.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Steely-vented Hummingbirds are quite distinctive in lateral or dorsal view, with a somewhat chunky four-inch body and a rump of rainbow hues (above). Like the rufous-tail, this species is sexually monomorphic. It ranges from Nicaragua to Venezuela, although the South American population may actually be a separate species--the Blue-vented Hummingbird, A. hoffmanni.

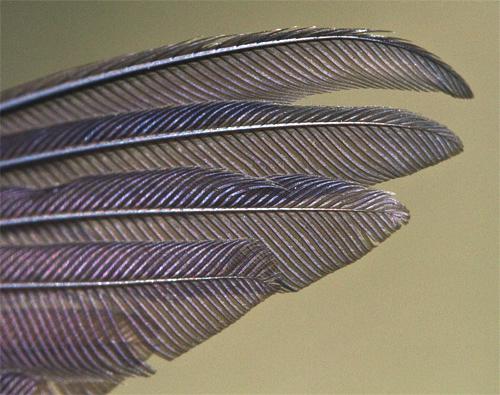

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center By far the largest hummer we caught at Ujarrás was the six-inch-long Violet Sabrewing, Campylopterus hemileucurus, whose massive wings had stout feathers with amazingly wide waxy-looking shafts (above).

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center A male Violet Sabrewing (above) has hints of green in his back but the predominant color is a striking metallic purple. White tail-tips contrast starkly with darker hues as a male approaches. You can also tell he's getting close by the clacking of his wings. This is one BIG hummingbird!

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Like their male counterparts, female Violet Sabrewings have long, black, decurved bills (male above), but otherwise they are sexually dimorphic. The female's plumage is far plainer: Green back and head with a white breast and tail tips, and only a hint of purple on the throat. We caught no female sabrewings in the Chayote fields, although they likely were there. The species is primarily Central American occurring from southern Mexico to western Panama.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The next-biggest hummingbird among the Chayote was the five-inch Green-breasted Mango, Anthracothorax prevostii, among which adult males (above) are metallic green with a central black stripe bordered by blue. (CAVEAT: Although most authorities state this species is sexually dimorphic, there is some indication adult females occasionally resemble males, probably with less black on the keel and throat.)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The more typical female Green-breasted Mango (above) has a green back, but the breast is white with a long vertical keel stripe of green and black.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Both sexes of Green-breasted Mangos have reddish tails, but in adult males (above) the color is much more metallic and intense. Tips of outer tail feathers in females are white. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The one other species we netted in the "largish hummingbird category" (four inches or more) was the Brown Violetear, Colibri delphinae, We nicknamed this one the "stealth hummer" because it's overall appearance was military, with a dull brown back (above) and gray-brown belly (below).

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Brown Violetears may be drab in dorsal or ventral view, but head-on they show bright metallic colors (below): A bright bluish cheek that gives the species it common name, plus an iridescent gorget that includes several shades of blue and green.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Brown Violetears are sexually monomorphic and are relatively uncommon, so we were pleased to get to handle two individuals. This is a species that hangs out primarily in forest canopies from Central America into northern South America; it's interesting that disjunct populations occur as far away as Trinidad and Brazil.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center From the bigger hummers we move to the smallest on our Ujarrás study site: Scintillant Hummingbird, Selasphorus scintilla, a congener of the Rufous Hummingbird, S. rufus, that breeds in western Canada and the northwestern U.S. and occasionally shows up in winter across North America. The adult male Scintillant in the photo above had an amazingly brilliant and wide gorget that flared out on the posterior corners.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Scintillant Hummingbirds are endemic only to Costa Rica and western Panama. Weighing just two grams as adult males (above), the species is only slightly larger than the world's smallest hummer, the Bee Hummingbird, Mellisuga helenae, of Cuba. (By comparison, adult male Ruby-throated Hummingbirds typically weigh about 2.5 to 3 grams.)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Adult Scintillant Hummingbirds are sexually dimorphic, but immature males resemble females with rusty tails tipped in white. Thus, based on a dorsal view we can't be completely sure of the sex of the bird just above.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center However, a view of that bird's non-metallic gorget (above) shows flaring like that in the image of the adult male, so we're guessing it's an immature male.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Had we thought to look at the wing feathers of that supposed immature male Scintillant, we might have been able to confirm its sex. It's our understanding the lead (#10) primary feather (above) of the adult male Scintillant Hummingbird is curved and sharply tapered, which gives the bird a distinctive wing trill during courtship. That said, we don't know for sure whether immature males have this wing shape.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Adult male Scintillant Hummingbirds are spectacular in flight, zipping among flowers such as the above-pictured Blue Vervain, Stachytarpheta frantzii, flashing their gorgets at competitors and nearby females.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The intended result of all that gorget-flashing is the male Scintillant Hummingbird will copulate with a a female that will lay an egg or two in a tiny lichen-covered nest like the one above, found in a Coffee shrub a few feet off the ground by Ernesto Carman Jr. and Ela Mayorga Villanueva.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another small hummer we encountered in our nets was the Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigulari (above), which more than made up for its diminutive body size with its lengthy tail and long, decurved bill. To say this bird stretches four inches is rather misleading, as shown when you compare its body to the size of the bander's thumb. The species breed from southern Mexico into northwestern South America.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Stripe-throated Hermit's inch-and-a-half bill is yellow at the base of the lower mandible and decurved, the latter characteristic allowing it to probe long tubular flowers such as those of the Acanthaceae.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Stripe-throated Hermit's tail is also quite long--especially its central rectrices (above). This is a common but not universal characteristic among hummingbirds in the Hermit Subfamily (Phaethornithinae), all of which are sexually monomorphic. Incidentally, Sicklebills--with their sharply decurved mandibles--are also hermits.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We've been trying to capture a Stripe-throated Hermit ever since we started research in Costa Rica, but over in Guanacaste they never entered the aloe fields and stayed instead in the herbaceous level of the forest were our mist nets were not. Little did we know when we finally caught one we would learn the species has unpigmented skin in its feet (above), allowing a clear view of blood vessels in the tiny hummingbird's even tinier toes. Just amazing!

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another small hummingbird we expected and were pleased to find among the Chayote was the Garden Emerald, Chlorostilbon assimili, a species endemic to Panama and Costa Rica's Central Valley and southern provinces. Females (above) and immature males have gemstone-green backs, clear throats and bellies, and a long white post-ocular stripe that sets off the dark eye. A very important field mark in this species is the bill; it's completely black above and below.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Young males and female Garden Emeralds also have greenish flanks and tri-colored tails (above), the latter with a broad blue-green band and tips of white.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center As the immature male Garden Emerald matures he molts all his feathers, replacing everything white with that sparkling emerald color that gives the species its common name. Even the yellow-tinged plumage on the back of the youngster above will become darker green.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center In dim light (above), a male Garden Emerald sporting adult plumage looks almost dark. However, one can still make out the species' slightly forked tail and completely black bill.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center So here's an image of another smallish hummer with brilliant emerald-green plumage, but it's NOT a Garden Emerald. You'll recollect THAT species had a jet-black bill, and the bird in the photo above has a lower mandible that's mostly reddish-orange. What we have here is a congener in Canivet's Emerald, Chlorostilbon canivetii, which we're familiar with from our time in Guanacaste on Costa Rica's Pacific Coast. If you have an older field guide you'll find no mention of Garden Emerald or Canivet's Emerald because they were split in recent years from Fork-tailed Emerald; the two new species look different (at least with regard to bill color) and supposedly are geographically separated. Hmmm. So what's Canivet's Emerald doing over here in the middle of the Garden Emerald's range? We're not sure we have an answer but Ernesto tells us our numerous sightings of Canivet's this fall were the first recorded for the Ujarrás Valley.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Like Garden Emerald, Canivet's is sexually dimorphic, but young males confuse the issue by masquerading as females. Thus, the white-throated, white-breasted, white-post-ocular-striped individual above can't be sexed as far as we know,

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although some hummers have common names that aren't very intuitive, there's not much doubt with the male Violet-headed Hummingbird, Klais guimeti (above). This three-inch species has a crown and gorget that are unquestionably iridescent violet--so brilliant the bird could almost be alled the "ULTRAviolet-headed Hummingbird." The black bill is straight and rather short, and both sexes show a noticeable post-ocular white spot.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Violet-headed Hummingbirds are sexually dimorphic--the female has a bluish crown and grayish breast and throat--but the species is monotypic; i.e., it us the only hummingbird in its genus. It is fairly widespread, occurring from Honduras to Brazil. Both sexes show tiny white spots on tips of their tail feathers. This is one of those hummingbird species that forms leks during courtship; males gather at a communal spot and sing, apparently to attract females with a more-easily heard group chorus.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Yet another well-named species is the male Magenta-throated Woodstar, Calliphlox bryantae (above), whose gorget is so bright and metallic it almost hurts one's eyes.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center From the side the male woodstar isn't particularly distinctive, with a green back and rather long tail (above). If it faces you in direct light, however, you'd better grab your sunglasses. The species is sexually dimorphic, with the female lacking the gorget and having a shorter tail. The big white patch on either side of the rump is an important field mark in both sexes.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The tail of the adult male Magenta-throated Woodstar is noticeably long and is cocked upward during rather slow flight. Conversely, the body is held horizontally, giving what some observers say is an "insect-like" flight profile. This species is endemic to Costa Rica and western Panama; our sightings this fall in the Chayote fields were the first recorded for the Ujarrás Valley.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Folks often ask us about our "favorite" hummer, and for obvious reasons we usually say we like Ruby-throated Hummingbirds because they've taken us places we never imagined. Nonetheless, we also have a marked preference for another aptly named species, the four-inch-long Blue-throated Goldentail, Hylocharis eliciae. Of all the kinds of hummingbirds we've handled through the years, this is the one that still takes our breath away. Green head, metallic blue gorget . . .

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center . . . blood-red bill with black tip, rainbow-colored rump, and of course . . .

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center . . . a tail of precious gold! The degree and variety of iridescence in this species is indeed breath-taking. Blue-throated Goldentails are partly dimorphic, with the female lacking a blue gorget but still bearing those bright rectrices. This is another lekking hummingbird that is rather uncommon on the Caribbean slope, so we were pleased to find this colorful old friend we first met in Guanacaste in 2008. The species breeds from southern Mexico to Colombia. Our sightings of Blue-throated Goldentails this fall were the first recorded for the Ujarrás Valley.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center By comparison to the other 12 trochilids were captured at Ujarrás, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds might seem a little plain--especially when some of the adult males we caught bore metallic "red" gorgets that had faded and worn to a bronzy color (above). That said, ruby-throats can claim one attribute that can't be said of any of the 50 other Costa Rican hummers: They're the only ones that undergo long-distance migration, fledging in North America and then flying up to 2,000 miles (or more) to the Neotropics--and back. It's possible some of Costa Rica's hummingbirds migrate over short distances-- which could explain, for example, how Canivet's Emeralds were showing up at Ujarrás within the breeding range of Garden Emeralds--but nobody else can hold a candle to the ruby-throat's seasonal movements.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Ruby-throated Hummingbirds are sexually dimorphic, with the female lacking a red gorget and having white tips on her outer tail feathers. All young males also have white-tipped tails, and some have female-like white throats.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center That said, a significant number of immature males are adult-males-in-the-making (above); they exhibit pale-to-dark throat streaking and can have one or more red gorget feathers--especially by the time they get to Central American wintering grounds. By the time they return to North America to breed these young males have grown forked tails populated with pointy, dark-tipped feathers, and they have full red gorgets. By then they look like adult males because they are, and in the U.S. and Canada soon get down to the all-important business of defending territories and attracting females. So that's our gallery of 13 hummingbird species we captured in mist nets among the Chayote fields at Ujarrás. We only banded Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--our permit from the U.S. Bird Banding Lab limits us to applying bands to Neotropical migrants--but we certainly enjoyed handling and photographing those other 12 highly colorful resident Costa Rican species that hit our nets. From a scientific staindpoint we were impressed with Canivet's Emerald, Blue-throated Goldentail, and Magenta-throated Woodstar--three species that had never been recorded for the Ujarrás Valley. With so many opportunities to observe, capture, and photograph so many kinds of hummingbirds, we'll certainly be going back and hope you'll join us sometime soon for an Operation RubyThroat expedition to the Neotropics. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

POSTSCRIPT: We've been working with Holbrook Travel before the holidays trying to lay plans for an Autumn 2012 trip to Ujarrás to continue our work with Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. We just heard from Debbie Sturdivant, Holbrook Travel consultant since our very first Neotropical trip, that she has worked out logistics and will be able to offer the expedition at an even lower price than last year. The nine-day trip will be $1,495 for all land costs, plus air fare. Alumni of previous Holbrook trips qualify for a $100 loyalty discount. We haven't had time to design and post a new itinerary yet, but the expedition will occur on 10-18 November 2012 and essentially follows the schedule outlined for the 2011 Ujarrás Trip. Note that a few spots are also still available on our 2012 Guanacaste Trip (2-10 February) to band and observe hummingbirds in western Costa Rica. |

|---|

The Piedmont Naturalist, Volume 1 (1986)--long out-of-print--has been re-published by author Bill Hilton Jr. as an e-Book downloadable to read on your iPad, iPhone, Nook, Kindle, or desktop computer. Click on the image at left for information about ordering. All proceeds benefit education, research, and conservation work of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. The Piedmont Naturalist, Volume 1 (1986)--long out-of-print--has been re-published by author Bill Hilton Jr. as an e-Book downloadable to read on your iPad, iPhone, Nook, Kindle, or desktop computer. Click on the image at left for information about ordering. All proceeds benefit education, research, and conservation work of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. |

|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

If you Twitter, please refer

"This Week at Hilton Pond" to followers by clicking on this button: Tweet Follow us on Twitter: @hiltonpond |

Comments or questions about this week's installment? Send an E-mail to INFO. (Be sure to scroll down for a tally of birds banded/recaptured during the period, plus other nature notes.) |

Click on image at right for live Web cam of Hilton Pond,

plus daily weather summary

Transmission of weather data from Hilton Pond Center via WeatherSnoop for Mac.

|

--SEARCH OUR SITE-- For a free on-line subscription to "This Week at Hilton Pond," send us an |

|

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond." Please see Support if you'd like to make a gift of your own.

|

If you enjoy "This Week at Hilton Pond," please help support Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. It's painless, and YOU can make a difference! (Just CLICK on a logo below or send a check if you like; see Support for address.) |

|

Make credit card donations on-line via Network for Good: |

|

Use your PayPal account to make direct donations: |

|

If you like shopping on-line please become a member of iGive, through which 800+ on-line stores from Amazon to Lands' End and even iTunes donate a percentage of your purchase price to support Hilton Pond Center.  Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause!Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause!Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. |

|

BIRDS BANDED THIS WEEK at HILTON POND CENTER 21-30 November 2011 |

|

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS WEEK: * = New species for 2011 WEEKLY BANDING TOTAL 0 species 0 individuals 2011 BANDING TOTAL 46 species 2,064 individuals 197 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds 30-YEAR BANDING GRAND TOTAL (since 28 June 1982, during which time 170 species have been observed on or over the property) 125 species (30-yr avg = 67.6) 56,941 individuals (30-yr avg = 1,898) 4,485 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (28-yr avg = 160) NOTABLE RECAPTURES THIS WEEK

|

OTHER NATURE NOTES: --We were in Costa Rica through 20 Nov, returning to Hilton Pond Center for the Thanksgiving holidays and associated family matters. (It also rained a lot.) Thus, we banded no birds this week. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center |

Our citizen scientists

Our citizen scientists

Recently fledged male and female Green-breasted Mangos look alike and resemble their mothers, except they have broad streaks of chestnut

Recently fledged male and female Green-breasted Mangos look alike and resemble their mothers, except they have broad streaks of chestnut

but it's absolutely a Canivet's because of the reddish lower mandible. Based on the buffy edges to its head feathers, it also appears to be a very recent fledgling.

but it's absolutely a Canivet's because of the reddish lower mandible. Based on the buffy edges to its head feathers, it also appears to be a very recent fledgling.

Oct 15 to Mar 15:

Oct 15 to Mar 15: