|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

HALCYON DAYS . . . NOT! On the evening of 8 September a cold front was forecast in the southeastern U.S., with potential for bringing an early autumn wave of birds from breeding grounds up north. In eager anticipation, next morning we deployed our mist nets at Hilton Pond Center to capture and band some of these migratory wanderers--in part because we hoped they might be encountered again some day on wintering grounds in the Neotropics. As the day progressed we caught a whole potful of non-migratory birds from Northern Cardinals to Carolina Wrens and ended up with only two species--Chestnut-sided Warbler and Northern Waterthrush--that absolutely had to be northern migrants. (For a full account of what we banded during the post-cold-front week of 1-9 September, see last week's on-line installment.) Although we weren't exactly overwhelmed by migratory birds as the front passed through, we figured some birds might be trailing behind a bit so we continued running nets on 10 September. Alas, things were still very slow net-wise that day, with only Carolina Chickadee, Northern Cardinal, and House Finch the only captures by mid-morning--and all three were all non-migrants. Because it takes a lot of time to monitor nets on a regular basis, the lack of bird activity and other responsibilities brought us near to shutting everything down at about 10:30 a.m. Perhaps for psychic reasons we decided to wait until noon. Sure enough, during our 11 a.m. check we found in a net near the old farmhouse a largish blue and white bird that emitted a distinctive, familiar rattle-like call as it squirmed in the mesh: Megaceryle alcyon--a Belted Kingfisher!

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center During the past three decades at the Center we've observed many Belted Kingfishers (BEKI) patrolling the property and diving into the still waters of Hilton Pond to come up with small fish. Just last week, in fact, we were out on the dock and found our observation bench was covered by tiny fish scales--undoubtedly leftovers from a kingfisher meal the day before. Through our 32 years of effort we've even managed to capture a smattering of kingfishers --ten to be exact, six females and four males--most of which were snared by nets down near the pond. This week's Belted Kingfisher, however, was in a net very close to the old farmhouse--perhaps attracted by gurgling sounds from a pump that recirculates water in a small decorative pool.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We say "it" was attracted when we should say "she," for our birds was an obvious female. In most kingfisher species the slightly larger females are easily identified by being more colorful than males. Among Belted Kingfishers both sexes have very large heads adorned with spiky blue crests and are mostly blue on their backs, wings, and tails. Both also have a blue belt across the upper chest with varying amounts of rust mixed in--immature females may have as much rust as blue--but females of any age have a second completely rusty belly band that sets her off from her less-brightly plumaged mate. (NOTE: Males occasionally have rufous flanks and a hint of a rust-colored belly band, but it's never complete.) It's hard to hold a big Belted Kingfisher to show off all its characteristics, but a few winters ago we did photograph a perched female whose image above nicely illustrates her characteristic double-belted breast and belly.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We've always thought kingfishers have interesting shapes. Their wings are relatively long--Belted Kingfishers are very good fliers and in some cases migrate over long distances from nesting areas in Canada to wintering grounds in Latin America--and the wing bones are strong enough to avoid breakage during a hard dive into a water surface. A kingfisher's body is chunky, with one of its most noticeable morphological traits being a huge head with large dark eyes and an startlingly long bill (above). Kingfishers spend lots of time perching on the edges of ponds, streams, and rivers, so big eyes undoubtedly help them spot prey in waters below, while an enormous head provides a place to anchor muscles that control the bird's amazingly strong bill.

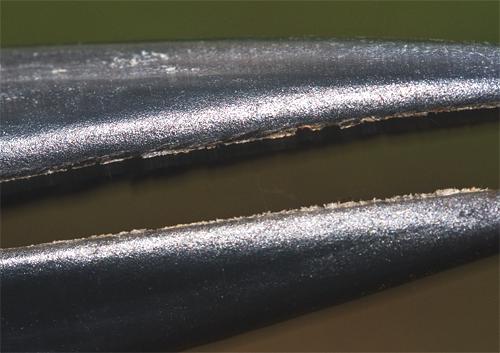

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center First time we captured and handled a Belted Kingfisher back in 1987 we were very careful not to let the bird peck us with its menacing mandibles. We quickly learned that kingfishers do not peck; they make use of considerable jaw musculature to clamp down very tightly with that long, straight bill. Ouch! And clamp they can--which makes perfect sense when we remember the bird must dive into water to grab a wiggly, slimy, smoothly scaled fish and hold on tight if its evasive lunch is to be served; a weak bill just wouldn't get the job done. The clamping power of the kingfisher's bill is what hurts when a bander gets bitten; the grip is almost vise-like and--to make matters worse--both mandibles are edged with tiny irregular serrations (above) that serve to hold the slippery fish--or the bander's finger--ever more tightly. Double ouch!

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center While our newly captured Belted Kingfisher was testing her bite on our digits (Ouch!) we were able to get a rare photo of her tongue. With long-billed birds such as woodpeckers and hummingbirds the tongue is even longer than the mandibles, but in those particular species the structure serves a different function. In hummers, of course, the tongue extends and retracts several times per second as the bird laps up flower nectar, while a woodpecker uses its barbed tongue to extract insect grubs from within decaying wood. In the kingfisher--which captures relatively large prey items with its bill and swallows them whole--a long lingual structure would get in the way, so a tiny, almost vestigial tongue is an important adaptation. We should mention that Belted Kingfishers, despite their name, are almost as likely to chomp on frogs, salamanders, crayfish, lizards, snakes, insects and spiders, and even small mammals such as mice and voles.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We were curious about the probable age of the female kingfisher we caught this week and referred to Peter Pyle's Identification Guide to North American Birds, Part 1--also known as the "Bird Bander's Bible." Pyle pored over thousands of publications and many more individual banding records to determine plumage characteristics and measurements that might be used to sex and age various bird species. In the case of Belted Kingfishers, Pyle reports that the #6 secondary wing feather in immature BEKI has a wide shaft and small crescent of white on the tip, which was indeed the case with our bird. In addition, among immature female kingfishers the two central tail feathers--just one of them shows in the photo above--a long dark area bordering the shaft is deeply scalloped. Thus, our bird was an immature female that hatched in 2012. One is not likely to see such nuances through binoculars or at backyard feeders, but they are a big help when ageing or sexing a bird in the hand.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The enormous bill of the Belted Kingfisher doesn't just function to capture prey; in fact, it is a digging tool. Most kingfisher species use stout bills to excavate burrows in bare earthen banks along ponds and rivers and even highway cuts and sand/gravel pits. (Males also have been known to excavate a roosting burrow near the one used for the nest.) We have no idea where our Hilton Pond kingfishers nest because there are no such embankments nearby, save those covered by densely growing Kudzu vines. It may be their burrows are ten miles west or east along the Broad or Catawba Rivers and that our birds simply disperse and drop by the Center on days when local fishing looks good. In any case, a Belted Kingfisher pair reportedly collaborates to dig a burrow that may extend ten feet or more, sloping upward slightly to a small nesting chamber. The female lays 5-8 eggs incubated for up to three-and-a-half weeks by both sexes, and mates also team up on feeding their young for another 27 days or so. (Note that this whole process can take up to 55 days, which is a LOT of time to devote to reproductive activity. No double-brooding in a given year by Belted Kingfishers, we'll bet.) Burrow nests--which likely take a great deal of effort to excavate--may be used year after year by the same pair, meaning that bones and fish scales and crayfish exoskeletons accumulate over time. We've always thought it might be possible to locate a kingfisher nest by odor because adults don't exercise much nest sanitation after regurgitating dead fish to their young. Chicks apparently not only defecate in the burrow but also throw pellets containing indigestible prey parts. What a mess they must be living in by the end of the nesting period!

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center And now for our obligatory note about kingfisher taxonomy. Traditionally, all kingfishers were placed in one family, Acedinidae, but DNA studies have caused ornithologists to split the group into Water Kingfishers (Cerylidae, including our Belted Kingfisher and the brightly plumaged Ringed Kingfisher, above, that we photographed in Costa Rica); the Halcyonidae (Tree Kingfishers of the Old World, plus Australian Kookaburras); and Dacelonidae (African Dacelonid Kingfishers). Even this taxonomy is in flux, so don't be surprised if there's more lumping and/or splitting of kingfishers in the near future.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Unlike mammals that use their clawed feet to excavate burrows, kingfishers do dig primarily with their bills. That's understandable when we examine the legs and toes of our Belted Kingfisher (above). This species' lower appendages are adapted for perching and not much else, being very short and too far back on the body to allow walking on the ground. The toes are somewhat fleshy, and digits three and four are fused at their base in a condition known as "syndactyly." (By comparison, songbirds and raptors have three unfused toes in front and one in back called "anisodactyly," while woodpeckers have a two-plus-two configuration, or "zygodactyly." In some kingfisher species the fourth toe is missing completely.) So what's the function of syndactyly in kingfishers? We don't know for sure but some experts suggest fused toes allow the foot to be used as a shovel to expel sand from tight confines of a burrow under construction.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The title of this week's photo essay says our encounter with a female Belted Kingfisher did NOT make for "Halcyon Days." The term Halcyon happens to be the genus name for several species of Old World kingfishers, the word being derived from the Latin word alcyon. Legend has it kingfishers laid their eggs on floating nests on the ocean and that two weeks of calm seas were required for incubation, a period eventually known as Halcyon Days. The phrase has broadened to mean a time of peace--something we didn't get from the Belted Kingfisher we netted this week. No, this squirmy loud-mouthed immature female showed nothing but apparent ingratitude for her banding experience and chose instead to demonstrate just how hard she can bite by clamping down more than once on our unprotected fingers (above). Our pinkie, in particular, understands full well how a minnow must feel when a kingfisher dives in and--with a stout bill that is her business end--grabs her next meal from the murky depths of Hilton Pond. Ouch, again! All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center This week we're celebrating executive director Bill Hilton Jr.'s 66th birthday with a special funding opportunity through Causes. If you'd rather, you also can donate via Network for Good All contributions are tax-deductible |

|---|

The Piedmont Naturalist, Volume 1 (1986)--long out-of-print--has been re-published by author Bill Hilton Jr. as an e-Book downloadable to read on your iPad, iPhone, Nook, Kindle, or desktop computer. Click on the image at left for information about ordering. All proceeds benefit education, research, and conservation work of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. The Piedmont Naturalist, Volume 1 (1986)--long out-of-print--has been re-published by author Bill Hilton Jr. as an e-Book downloadable to read on your iPad, iPhone, Nook, Kindle, or desktop computer. Click on the image at left for information about ordering. All proceeds benefit education, research, and conservation work of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. |

|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

Comments or questions about this week's installment? Send an E-mail to INFO. (Be sure to scroll down for a tally of birds banded/recaptured during the period, plus other nature notes.) |

Click on image at right for live Web cam of Hilton Pond,

plus daily weather summary

Transmission of weather data from Hilton Pond Center via WeatherSnoop for Mac.

|

--SEARCH OUR SITE-- For a free on-line subscription to "This Week at Hilton Pond," send us an |

|

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond" with students, teachers, and the general public. Please see Support or look below if you'd like to make a gift of your own.

|

If you enjoy "This Week at Hilton Pond," please help support Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. It's painless, and YOU can make a difference! (Just CLICK on a logo below or send a check if you like; see Support for address.) |

|

Make credit card donations on-line via Network for Good: |

|

Use your PayPal account to make direct donations: |

|

If you like shopping on-line please become a member of iGive, through which 950+ on-line stores from Amazon to Lands' End and even iTunes donate a percentage of your purchase price to support Hilton Pond Center.  Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase through them earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause! Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase through them earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause! Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. |

|

BIRDS BANDED THIS WEEK at HILTON POND CENTER 10-14 September 2012 |

|

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS WEEK: * = New species for 2012 WEEKLY BANDING TOTAL: 11 species 30 individuals 2012 BANDING TOTAL: 31-YEAR BANDING GRAND TOTAL: (since 28 June 1982, during which time 171 species have been observed on or over the property) 126 species (31-yr avg = 66.6) 57,903 individuals (31-yr avg = 1,868) NOTABLE RECAPTURES THIS WEEK: Mourning Dove (1) |

OTHER NATURE NOTES: --A male American Goldfinch trapped on 13 Sep was pretty old; we banded him locally in March 2008 in full adult plumage that takes two years to acquire, so now he's in at least his seventh year. One of his eyes was closed from conjunctivitis and we're hopeful he'll recover. Another AMGO netted on 13 Sep was a recent fledgling--our first young goldfinch of the year. American Goldfinches are likely the last songbird to breed here in the Carolina Piedmont, so we expect more fledglings in coming days and weeks around Hilton Pond. --If you missed last week's photo essay it was about the beginning of Fall Migration at Hilton Pond and and some of the resident and migratory birds we banded. Avian mug shots galore! See Installment #550. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center |

Please report your sightings of

Please report your sightings of