|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

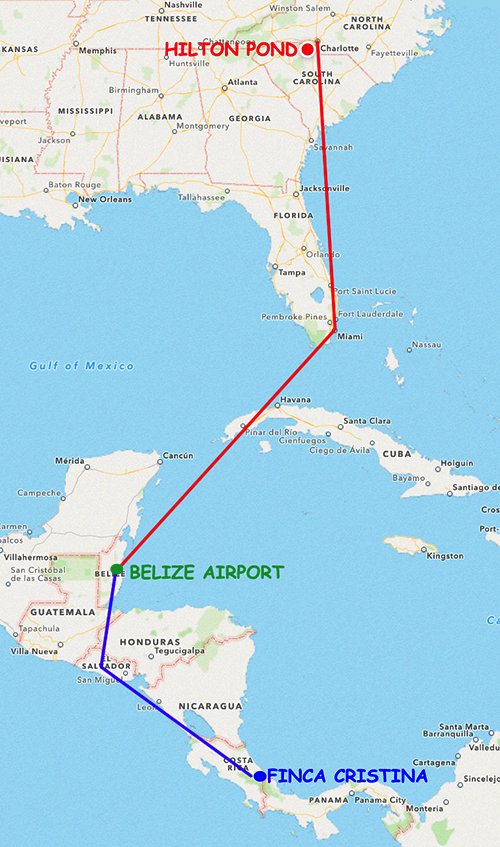

"HIGH WATERS" IN BELIZE: PREFACE In late February Dr. Bill Hilton Jr. (principal investigator for Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project) and Ernesto M. Carman (long-time guide, interpreter, and colleague) visited Pico Bonito in northern Honduras to determine if the area might be suitable for expansion of ground-breaking long-term studies of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds on non-breeding grounds in Central America. Alas, few RTHU were seen on Honduras' Caribbean Slope, so Hilton and Carman (AKA "The Omega Group") continued on by air for a planned trip to Crooked Tree Sanctuary in north central Belize. Through Holbrook Travel, Hilton had organized five research expeditions to Crooked Tree beginning in 2010 and was eager to return with a new group of citizen scientists to see what new knowledge might be gleaned. The preceding two "This Week at Hilton Pond" photo essays (Honduras Part 1 and Honduras Part 2) were about the excursion to Pico Bonito and vicinity, while the one below chronicles our just-completed foray to Belize. (NOTE: Some bird photos in this account are from our files of previous expeditions; we also appreciate and acknowledge use of a few images taken by this year's trip participants.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center PRE-EXPEDITION--6 & 7 March 2013

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Well before dawn on 6 March, the Omega Group departed the Lodge at Pico Bonito for a 2.5-hour ride to San Pedro Sula--home of the busiest airport in northwestern Honduras. There they boarded a TropicAir propeller plane (above) for their one-hour flight to Belize.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center TropicAir's vessel is an intimate aircraft--ten passengers plus pilot and copilot--so we clambered aboard first to be up close to the action. We couldn't see out the front, but we did have great panoramas out the side windows.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Being up front we were privileged to look at all the knobs, switches, and gizmos that explain why flying even a small passenger plane requires hundreds of hours of training. We especially enjoyed being able to follow flight progress on a full-color navigation screen (above) that showed we were flying almost due north for nearly the entire trip.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We literally skimmed the clouds for most of the flight--barely above 6,000 feet and with an excellent view (above) as we approached the Belize mainland. With the Caribbean Sea on the right, we were struck by how much standing wanter there was in the Belizean coastal plain. (Later in our photo essay we'll offer more commentary about this particular observation.)

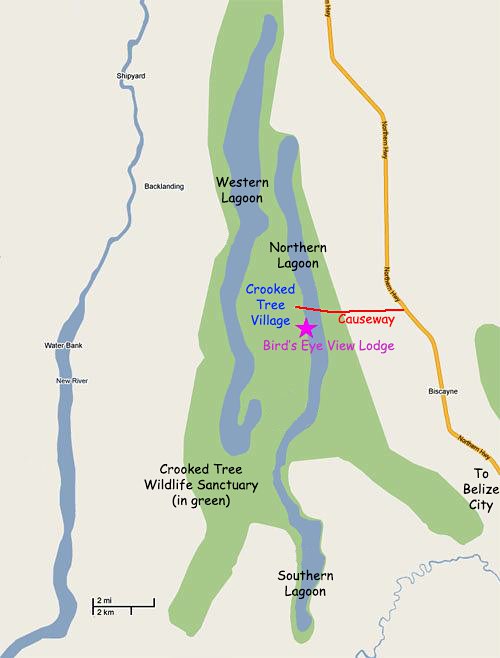

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The runway at Belize airport runs east-west, so the pilot did a fly-around to get into position to land at what--from our position up front--looked like a very small landing strip; nonetheless, he brought us in smoothly and professionally. After getting our bags and clearing customs we were met in the airport parking lot by old friend Michael Tillett, a driver/guide from Bird's Eye View Lodge. Michael loaded our luggage and off we went on the familiar 75-minute ride up the "new" Northern Highway toward Crooked Tree Sanctuary.

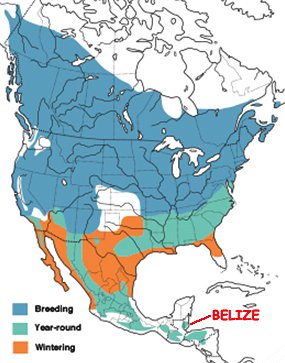

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Folks often ask why we chose Belize as one of the countries in which we conduct hummingbird studies. After several years of e-mails, library and Internet research, and conversations with birders, we finally learned from British bander Nick Bayly that he often saw concentrations of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (RTHU) at Crooked Tree Sanctuary, but only during a 2-3 week span in late February and the first half of March. Nick astutely correlated the presence of these hummers with the annual bloom of Cashew trees, originally planted a few centuries ago at Crooked Tree by the Brits when the country was called British Honduras.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Cashews, Anacardium occidentale, are not native to Belize--they were imported from northern Brazil--but they do bloom right about the time when many ruby-throats are beginning northbound migration. With Belize being on the Yucatan Peninsula, it's probably a good place to start tanking up before embarking on what may be a 500-mile non-stop flight across the Gulf of Mexico. Cashew trees produce masses of white flowers that quickly turn red (above), and each of these tiny quarter-inch blooms contains energy-laden nectar.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. Archilochus colubris, like the female above visit Cashew blossoms for their sugar content, but such carbohydrates merely fuel the hummers' efforts to catch hundreds of tiny spiders and insects such as gnats, fruit flies, aphids, mosquitoes. As soon as the Omega Group got to Bird's Eye View Lodge--warmly greeted by ebullient hostess Verna Samuels and her team--we checked into our rooms and also deployed four portable hummingbird traps. Baited with sugar water, these "Dawkins-style" traps attract hummers that, in turn, become confused and can't find their way out. Because Bird's Eye View Lodge owner Denver and Norma Gillett and their guides typically keep feeders stocked prior to our arrival in Belize, we trap reasonable numbers of RTHU in the Lodge's garden area.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Despite Denver's sugar water feeders, we saw no Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in the Lodge garden; the usual Rufous-tailed Hummingbirds and Green-breasted Mangos investigated and entered the traps, but even these were many fewer than in previous years. We concluded low hummer numbers occurred because the feeders had only been up for a week or two, and with good reason. As Michael explained to us on the ride from the airport, in 2013-14 northern Belize experienced a phenomenally long and wet rainy season with massive flooding. The causeway leading from the mainland to Crooked Tree Village (see map above) was at one point under more than FOUR FEET of water, meaning the Northern Lagoon was well above capacity.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When the lagoons are full, shoreline flooding occurs--which means Bird's Eye View Lodge itself goes partly under water. A month before we arrived there as still a foot of water in the Lodge's lower rooms and clean-up crews had to work like crazy to have the place ready for guests. Usually when we get to Crooked Tree in early March lagoon levels have dropped far enough to expose 30-40 feet of beach in front of the Lodge; as shown in the photo above, this year the water was still exceptionally high. There was no beach at all, and levels dropped little if at all during our stay.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center All this high water had repercussions. In our case, it meant hummingbird feeders weren't hung and maintained until shortly before our arrival. The causeway road and other roads around the village were a mess. And, in the bigger picture, water was so deep the usual assemblage of waders and waterfowl did not yet have places to eat, so the view across the lagoon was like that above.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Compare the previous panorama to a 2013 photo (above) taken from a similar angle. Hundreds of thousands of egrets, herons, ducks, kingfishers, cormorants, terns, pelicans, and storks (including Jabiru) were not present for the first time in our five years of visiting Crooked Tree. Even so, we were glad to be back--soon to welcome our next team of citizen scientists who would help us determine if all these high waters had an impact on our hummingbird research.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Having flown in on 6 March and gotten over the initial shock of a deep lagoon, almost no water birds, and few hummers at the Lodge, the Omega Group spent most of the next day exploring study sites we had used in previous years. (We also enjoyed the Lodge's latest addition, above, that included an expanded reception area and gift shop and a big, comfortable sitting room with Wi-Fi AND air conditioning.) As we scouted we were looking for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--especially those foraging on low-growing Cashew trees where the incoming team might be able to capture them in mist nets. Despite their absence from the Lodge, we saw fair numbers of RTHU on our old study sites in and around Crooked Tree Village, so we went to bed early that evening confident we'd be able to band some ruby-throats during six days with the team in the field. DAY ONE--8 March 2013 On the morning of 8 March the Omega Group re-boarded the Bird's Eye View Lodge van, this time driven by head guide Leonard Tillett (below right)--our go-to guy in Crooked Tree.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We got to the Belize City airport by late morning for the initial arriving flight that bore first-time Operation RubyThroat participant Lisa Spellman (above). Lisa (of Berwyn IL) bounded through customs and immigration with a smile on her face, closely followed by Ethelyn Bishop (Laurel MD). Ethelyn is one of our beloved ORT "groupies," having been with us previously to Nicaragua (2013), to Guanacaste in western Costa Rica (2012), and TWICE to Ujarrás (2011 & 2013) on Costa Rica's Caribbean Slope. Flights continued to touch down during the early afternoon, eventually bringing Deb Jenkins (Atlanta GA), Joe Lynch (Wading River NY), Elaine Maas (Stony Brook NY), Nancy Meier (Catonsville MD), and Jenine Pontillo (Pomona NY). Nancy and Jenine were also groupies, the former having been to Ujarrás (2011) and Nicaragua (2013), and the latter to Ujarrás (2013). It was a smaller-than-usual group but we were certain based on their bios and past friendships that all seven folks would help us accomplish our research goals for 2014 in Belize.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center It was 4 p.m. by the time the last flight had arrived and Leonard had stowed luggage, so we headed back up the Northern Highway, starting our "Trip Bird List" along the way. We got to Bird's Eye View Lodge a half-hour before supper--time for Verna and Therese to orient the group, for the team to check in, and even for a quick look at a few birds in the proximity. Unlike any other time we've been to Crooked Tree, a pasture right behind the Lodge was still so flooded from the heavy rainy season that from the front porch Blue-winged Teal, Minla cyanouroptera (above), could be seen dabbling around.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In the same flooded field our newly arrived group observed American Coots, an Osprey, and even a be-plumed Snowy Egret, Egretta thula (above) startling potential prey by waving its yellow foot. This pristine white bird was in breeding condition, its plumes--known in French as aigrettes--fluttering in the breeze.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Despite high water in the lagoon, as the group gathered in the dining room for supper we could see an even larger wading bird posing just offshore. This time it was a Great Egret, Ardea alba, standing erect as the sun settled on the horizon.

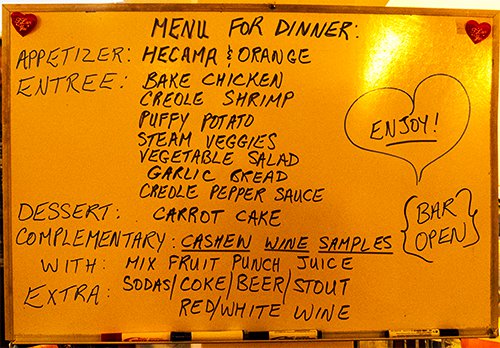

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Meanwhile, dining room evening hostess Evelyn had posted the menu (above) for the group's first meal--a delightful, tasty assortment of ethnic Creole dishes punctuated with a shot of the Lodge's signature Cashew wine. The food is superb and served buffet-style, so you can always eat your fill. We've dined in lots of Central American restaurants and lodges, but in our judgment nothing tops the fare at Bird's Eye View Lodge. (Great victuals and air conditioning are two of many reasons we stay there!) After supper the team retired to the outdoor patio adjoining the dining hall for an orientation session and introductory lecture about the history of our Operation RubyThroat research in Belize. Most evenings during the week a member of the group also gave an informal presentation about his or her life in the outside world--followed by an analysis of the day's banding efforts and additional info about hummingbird natural history. DAY TWO--9 March 2013 An Operation RubyThroat tradition is for Ernesto to rap woodpecker-like on everyone's door each day, rousing the team in time for an filling breakfast. We appreciated morning chef Stephanie for getting up an hour early on our field days to prepare a hot meal; this allowed us to depart the Lodge well-fed by 6 a.m. After all, as trip leader Hilton likes to say, "The early worm catches the bird." Along the way to the study site we called out "Happy Baron Bliss Day" to local folks already up and about in their yards. British-born Henry Edward Ernest Victor Bliss (born 1869, died 1926) was an engineer who made his fortune in oil speculation. CLICK ON MAP ABOVE TO OPEN A LARGER VERSION All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Based on pre-trip scouting by the Omega Group, the team headed for one of our established study sites (see aerial image above); in this case, it was the northern-most one called Reynolds Woodlot (REY), where in previous years we had reasonable success capturing Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--plus other Neotropical migrants. (NOTE: When you click on the map above you might want to leave the larger version open for future reference.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Reynolds Woodlot (above) is similar to several other productive sites at Crooked Tree, the most important attribute being low-growing Cashew trees with plenty of blooms that might attract Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. A limited amount of undergrowth enables easy navigation on foot for mist net deployment and monitoring. When we arrived that first morning the first hour was devoted to teaching participants how to remove nets from their storage bags and place them on 10-foot-long steel pipes. Once the nets were prepared, Ernesto led the team into the bush (above) to various predetermined net lanes we had used in past years.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Erecting each net required driving a three-foot length of steel reinforcing bar into the sandy soil so one pole can be slipped over this rebar (see photo above, with Elaine Maas holding and Deb Jenkins pounding). The net is extended, a rebar is driven for support at the other end, and the 8' x 42' net is unfurled. Properly deployed, a mist net literally blends into the mist and becomes nearly invisible to birds.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As each nets was opened, at least one team member stayed nearby to watch for captures. In tropical situations it's essential that birds in a net be kept in the shade and removed quickly. When a bird was netted the responsible team member called for a member of the Omega Group to do the extraction. In the photo above, Nancy Meier assists Ernesto in removing a bird from the mist net.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Once removed, the bird was placed in a white lingerie bag that provided for temporary restraint. The mesh is soft and allows the birds to breathe, and it's easy to see what's inside. In the photo above, 'Nesto blows through the bag mesh to move bird feathers as he reads the number on the leg of a previously banded bird.

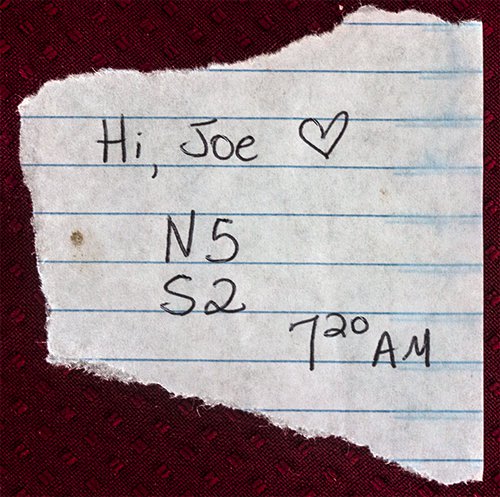

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After the bird was safely into the bag, the net tender scribed a small piece of paper (above) with time of capture (7:20 a.m., or 0720 in "military time"), the location (N% for Net 5), and which of the four shelves caught the bird (S2 for the second shelf from the bottom of the four shelf net); this paper tag went into the bag with the bird. On one occasion, the scribe at the banding table (i.e., Joe) got a mysterious love note (above) from one of the net tenders in the field. (We suspected it was written by Elaine, but no one knew for sure. As the only male on the seven-person team, Joe was very popular.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center On a typical morning we deployed 10-12 mist nets and on that first day in the field things actually worked as they were supposed to. By the end of the morning the group had netted four immature male Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--all with incomplete red gorgets (above) and each of which received a color mark of temporary purple dye. The color mark wears off after about a month but allowed us to monitor our banded birds after release.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Portability and improvisation are all-important in field work, and the team had to jury-rig a banding table from materials at hand: Drink bottle cases and an old-four legged white table became the banding platform, while a scribe (Elaine taking her turn, at right) sat on a green plastic flower pot while a scribe-in-waiting (AKA, the "scribesmaid," in this case Joe) perched on an old paint bucket. As master-bander-in-charge, Bill (relieved upon occasion by banding trainee Ernesto) got to sit in a real plastic chair borrowed from the Lodge.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The banding platform may appear chaotic (above), but the bander knows where the tools are. The photo depicts various sizes of bands and banding pliers, measuring devices (including a digital scale and caliper), a hand lens, and special tools for forming hummingbird bands.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When a new bird species was netted, bagged, and brought to the banding table, the bander called in the team for "show and tell" (above). This gave everyone a close and intimate look at all the kinds of birds we captured.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As is their method, the Omega Group was always careful NOT to identify a new bird species either in the net, in the lingerie bag, or in the hand. Instead, team members were asked to use their field guides (above) to try to figure out identifications on their own, paying careful attention to written descriptions, field marks, and range maps. Although some folks initially found this to be frustrating, everyone finally agreed it was better to puzzle through an I.D. than for someone to blurt out what the bird was.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center According to the stipulations on our master banding permit issued by the federal Bird Banding Laboratory in Laurel MD, we are allowed to band in Belize any bird species that is a Neotropical migrant with a chance to be encountered again on breeding grounds up north. This naturally includes our target species (Ruby-throated Hummingbirds), but also North American Wood Warblers and migratory vireos, tanagers, flycatchers, etc. The permit does not allow banding of non-migrant, resident species such as the Black-headed Trogon (male above).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Also unbandable was the Dusky-capped Flycatcher (above), a year-round resident at Crooked Tree. Even though we couldn't band these non-migrants, there were plenty of opportunities for up-close examination and photography.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Some or our photographers even used cell phones (above) and iPads to collect their images, as when Ernesto documented our capture of this bandable adult male American Redstart later in the week. No longer is it necessary to carry a big, bulky single lens reflex camera into the field--although some of us still enjoy doing so!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In addition to capturing four immature male Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, the team also netted two each of Magnolia Warbler (both female) and Black-and-white Warbler (male & female), and one each of Hooded Warbler (male, above), American Redstart (male), Yellow Warbler (male), and Tennessee Warbler (unknown sex). This was a pretty good tally for a first day in the field--especially since at least the first hour or was devoted to getting oriented and learning how to erect mist nets.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One nice thing about returning to the same location year after year is the potential for recapturing birds already banded. Such was the case on our first day in the field in 2014. In addition to all the new captures enumerated above, the team also netted THREE Neotropical migrants from previous years. The first was a Magnolia Warbler female (above) we banded as a second-year bird on 15 March 2012--putting her in her fourth year. A second female Magnolia Warbler was banded on 1 March 2013, while the other return was a female Black-and-white Warbler banded on 14 March 2013; both these were now after-second year birds that hatched not later than in 2012. All three returns were banded in this very same Reynolds Woodlot--undeniable evidence of very precise site fidelity in Belize after these individuals migrated at least twice from and to breeding grounds in North America. Such data are very important in providing rationale to landowners and governments for protecting habitat on BOTH ends of these birds' migratory paths.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When not at the banding table for show-and-tell or serving as scribe and scribe-in-waiting, group members stationed themselves where they could watch one or two mist nets. Waiting for birds to hit nets was a little tedious when things were slow, but during lull times came opportunities to scan the woodlot for birds such as the male Vermilion Flycatcher, Pyrocephalus rubinus, above. Notice the asymmetrical molt in his left wing.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although ruby-throats were indeed present, by far the most common hummer in Reynolds Woodlot and on Crooked Tree in general was the Rufous-tailed Hummingbird, Amazilia tzacatl (above). This monomorphic species breeds locally--we had several reports from folks in the village there were active rufous-tail nests in their yards during our stay in Belize. We suspect Rufous-tailed Hummingbirds may be the most common trochilid in Central America--except, perhaps, September through February when ruby-throats have come south.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center For net watchers there were also chances to see other wild creatures beside birds. In the photo above, an unidentified swallowtail butterfly--very likely Giant Swallowtail, Papilio cresphontes (AKA Heraclides cresphontes)--oviposits on the leaves of a low-growing shrub. When her eggs hatch, her caterpillars will munch on foliage of this intentionally selected host plant. (NOTE: As always, if you'resure of the common or scientific name of any unidentified plant or animal on this page, please send the I.D. to INFO.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Shortly before noon we dismantled the banding table and called for the team to shut, furl, and bring in their mist nets, which we conveniently stowed overnight in the van with all of our field equipment. After the short ride back to the Lodge folks cleaned up a bit for lunch and helped set and bait with sugar water our four hummer traps in the garden. Almost immediately one of those ubiquitous Rufous-tailed Hummingbirds got snared (above), giving the team and other Lodge guests a close look.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After lunch, team members went off for showers and siestas while the Omega Group continued to man the Dawkins traps. Several more rufous-tails were captured, as was an apparent adult male Green-breasted Mango, Anthracothorax prevostii, until we shut down at about 2 p.m.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When folks had rested up a bit Ernesto offered his ever-popular "Four O'Clock Walk," a slow-paced ramble along the dusty roads that snake throughout Crooked Tree. Habitats in the village are amazingly varied, including a small slough that provided great looks at a Bare-throated Tiger Heron, Tigrisoma mexicanum (above). This short-necked wader occurs coastally in Mexico and all of Central America but can be found almost anywhere there's water on the Yucatan Peninsula, including Belize.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center High in a leafless deciduous tree not far from the tiger heron was a bird with a familiar shape (above)--the hunched-over posture of a diminutive Bat Falcon, Falco rufigularis. This little raptor--males are a mere nine inches long while females barely reach 12 inches--makes its living on large insects and small birds; the Bat Falcon is even active at dusk and dawn when it takes flying mammals that give rise to its common name.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Belize is home to a half-dozen truly black species in the Blackbird Family (Icteridae), all so unique they can be differentiated rather easily.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As the afternoon birdwalkers returned they encountered one of several pairs of Vermilion Flycatchers we find every year around the Lodge. There's usually at least one nest on one of the buildings, although this year nest construction seemed a little behind--perhaps delayed by the flooding. The female flycatcher (above), drab by comparison to her mate, spent a lot of time just flying from shrub to shrub or perching on a barbed wire fence around the pasture behind the Lodge.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Plumage of the male Vermilion Flycatcher (above) is always a sight to behold, with his brilliant red crest and undersides contrasted with a dark back and mask. Our guess is that Operation RubyThroat participants take more photos of this bird than any other land species at Crooked Tree--not only because the flycatchers are colorful but also because they always seem to strike photogenic poses.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center DAY THREE--10 March 2013 On our second field day we went back to Reynolds Woodlot, following our usual procedure of working a site at last twice during an expedition. (Besides, our first day there had been reasonably productive, with the capture and banding of four immature male Ruby-throated Hummingbirds.) The team was much more efficient, having mastered the art of deploying mist nets the day before. Despite their speedy, dedicated work we managed to catch and band only one RTHU--our first clear-throated adult female (above) of the year, bringing our 2014 total to five ruby-throats. Other Neotropical migrants banded on our second day in the field included one each of the following, all of which were second-year birds hatched in 2013: Yellow Warbler and Magnolia Warbler (both male); Summer Tanager (female); and White-eyed Vireo and Gray Catbird (both unknown sex).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Cent Once again, the highlight of the morning was the capture of returning birds we had banded on earlier expeditions--especially the appearance in our nets of a Yellow-breasted Chat bearing #2541-15803 (above). The well-worn appearance of this band suggested it was an "old" bird and a check of our archival data revealed it was first captured on 4 March 2011 as a second-year bird--making it a fifth-year in 2014 and our oldest banded bird in Belize.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The records showed we also recaptured this particular chat (above) last year on 1 March; all three encounters occurred in the Reynolds Woodlot. This is astoundingly precise site fidelity, indicating again that long-distance migrants come back to exactly the same locations in Belize each non-breeding season.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The return of the Yellow-breasted Chat was exciting, but the team wasn't done with recaptures on 10 March. Later in the morning they caught another old bird, this time a Northern Waterthrush banded on 4 March 2011 as an after-hatch-year, now after-fourth-year. And then they caught one more old friend: A White-eyed Vireo banded as a second-year bird on 14 March 2012 and recaptured again on 1 March 2013, now a fourth-year bird. It is indeed significant all these bandings and recaptures took place in Reynolds Woodlot, and it's these sorts of data that make long-term research at specific locales so important. Too often field studies only occur for a year or two, making it hard to find trends or discover facts about organism longevity, population changes, and--of course--site fidelity. In the big picture, five years at Crooked Tree isn't all that long, but we're already deriving Neotropical migrant information new to science.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Along with new bandings and recaptures our second field day also netted several resident bird species, including a male Black-headed Trogon, Trogon melanocephalus (above). This is the most common member of its family (Trogonidae) at our various Central American study sites.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Trogons (and fellow family members, the quetzals) are the only birds with a "heterodactyl" toe configuration; digits 1 & 2 point back and 3 & 4 point forward. (Woodpeckers also have a 2+2 toe arrangement but they are "zygodactyl," with outside toes 1 & 4 pointing back and 2 & 3 forward.) Trogons, despite their ferocious-looking mandibles, consume mostly insects and fruit. Their common name comes from the Greek word for "nibble"--not because they eat that way but because they excavate nest holes by gnawing on old trees.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Occasionally we catch birds in Belize that look very familiar to our citizen scientists but that are NOT Neotropical migrants. Such was the case with the bird above. Team members said they thought it resembled the House Wren that occurs commonly across the U.S. during the breeding season. And, in fact, our newly captured bird WAS a House Wren, Troglodytes aedon, but it was part of a non-migratory population that stays year-round at Crooked Tree. As such, this bird was not bandable.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center House Wrens are one of the more commonly seen LBJs (i.e., "Little Brown Jobbers") on our study sites in Belize, and they also nest in and around human-built structures at Bird's Eye View lodge. Faint barring on wings and rectrices are typical--as is the wren's habit of cocking up its tail. House Wrens show a great deal of site fidelity, seldom straying far from a location in which they have nested successfully.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center And speaking of site fidelity, we were delighted on 10 March when our project's most faithful follower in Crooked Tree--none other than Miss Khadija Georgiana Tillett (above)--came again to visit us in the field. We met Khadija on our first trip to Belize in 2010 when she and some friends wandered onto the study site and showed curiosity about our work. Of those three girls, Khadija has remained steadfastly interested and every year has volunteered to help out in the field on days when she's not in school. It has been fun to watch this beautiful hazel-eyed Creole girl grow and this year to learn of her plans to go to high school in Los Angeles in 2016 after she graduates from Crooked Tree Elementary. She's quite bright and is thinking about becoming a doctor; we're hopeful she will continue to do well.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When the net-watching team came in to meet Khadija they brought along a few more birds, neither of which was bandable. One was a very common species throughout grassy areas and former forested land in Central America: White-collared Seedeater, Sporophila torqueola (male above). A look at this bird's short, heavy conical bill once led taxonomists to believe it was an emberizid finch, but recent DNA studies place it in the Tanager Family (Thraupidae). Females are much more drab; their plumage resembles that of a female American Goldfinch in winter.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The bird in the photo above can fool even expert birders who fail to pay close attention to all its characteristics. At first glance the bird's yellow-green body and gray head might lead one to say "Tennessee Warbler," but that would be incorrect. Warblers have straight, pointed bills while the bird above has a slightly hooked bill with a small notch behind it--characteristic of birds in the Vireo Family (Vireonidae). And, in fact, this bird IS a vireo, albeit a non-migrant; it's a Lesser Greenlet, Hylophilus decurtatus. Like other vireos, the greenlet gleans adult and larval insects from foliage and often hangs around in mixed flocks of warblers and honeycreepers.

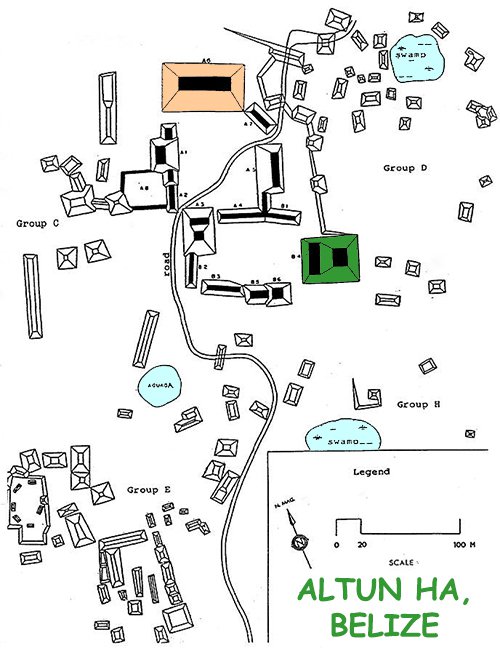

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After an eventful morning banding, examining, and photographing birds in Reynolds Woodlot, the team returned to Bird's Eye View lodge for lunch. Then we boarded Leonard's van for the 75-minute ride to south Altun Ha, a deserted Mayan city only a few miles from the Caribbean coast. After a warm greeting and introductory comments from old friend and Mayan expert Ann-Marie Avona, our participants sought a panoramic view by climbing the "tourist steps" (above) on A-6, one of the tallest temples (shaded tan in the map below).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Altun Ha is the modern name for a very old Mayan city. This extensive settlement covers nearly five square miles ("small" by Mayan standards) and was first inhabited about 200 BC. The central-most portion of the city includes as many as 500 structures, the largest being temple/tomb pyramids built in traditional Mayan stair-step style. Modern-day interest in the site increased after it was "re-discovered" in 1963 from an airplane. (Local residents, of course, were aware of the ancient city all along and in recent centuries used stones from Altun Ha to build homes in a nearby town.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Ann-Marie (above, in pink) is a gregarious Creole guide with comprehensive knowledge of the cultural and natural history of the area. We're astounded she remembers us from year-to-year, especially when you consider on cruise ship days as many as 3,000 tourists may visit Altun Ha!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Ann-Marie said archaeologists determined Altun Ha was constructed primarily during the Mayan Classical Period (200-900 AD) and that the city at its peak probably housed 10,000 or more people--half of whom may have gathered on the main square on festival or shopping days. Facing west is the 60-foot-tall Temple of Masonry Altars (above) that took a few hundred years to build and in which several priestly tombs were found. The structure's front stairway is flanked by carved heads at ground level; a unique round altar projects from the summit.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The temples are magnificent, but one of our favorite parts of Altun Ha is the half-mile walk down a wide trail (above) that leads to a large pond. This reservoir was created when the Mayans quarried stone for their buildings, after which it served as a source of water for the city. Because there was no archaeological evidence of wheel ruts, Ann-Marie said she believed the locals transported water from the pond to the plaza in a "bucket brigade," passing containers from person to person along the trail.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The trail wound through a dark tropical forest in which the silence was occasionally interrupted by the calls of an exotic bird or insect. In the quiet we tried to image what it was like for Mayans who walked the trail 2,000 years ago. Along the trail we found tapir tracks in the mud where a tall American Oil Palm, Attalea butyracea (above), with 20-foot fronds was in fruit.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center At the end of our excursion we were introduced to Ann-Marie's year-old granddaughter (above). We wondered if she will become the next generation of guides at Altun Ha, learning at her grandmother's knee about the rise and eventual decline and dispersal of the Mayan empire. On the way back from Altun Ha the conversation in the van took strange turns as our seven citizen scientists tried to come up with a nickname for this year's group. Some suggestions--later submitted to a team of impartial judges for consideration--were somewhat suggestive, while others would take far too much explanation to be of use. We gave the team another 12 hours for additional nominations and promised to have that all-important nickname for them by the following evening. DAY FOUR--11 March 2013 Having spent two days at the Reynolds Woodlot and banded five Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, we acted on comments from a couple of Crooked Tree residents who said they had been seeing good numbers of RTHU feeding in a pine-oak-cashew savanna west of the village. Thus, for our third day in the field we drove out into was we already knew was a very different habitat.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We had banded in previous years in a savanna at a site called Recia's Cashew Farm just south of the village. (If the aerial map isn't still open in your browser, click here.). However, when the Omega Group scouted Recia's a few days previously we saw essentially no ruby-throats and had already decided we probably wouldn't run nets there in 2014. As shown in the photo above of our new site--dubbed "GOV" because it sits on what we were told is land belonging to the government--the habitat was very different from Reynolds Woodlot. Instead of a shady forest with canopy and sub-canopy trees, the savanna was mostly a dry, sandy grassland with a scattering of trees and shrubs and lots of low herbaceous growth. This was also a much hotter place to work, so we were constantly reminding the team to drink water and stay hydrated. After a quick deployment of mist nets the team members settled into the shadiest spots they could find to watch for birds; their efforts were amply rewarded with the capture of an immature male Ruby-throated Hummingbird and six females, making a daily total of seven and bringing our 2014 number to 12. Reports we got from local guides about RTHU feeding on cashews in the pine savanna were apparently spot-on.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Despite warm temperatures the team also netted a respectable number of Neotropical migrants--some of which we might not think of as pine savanna inhabitants. Included in the total were: Three American Redstarts (two after-second-year males, above, and one second year female), two male Northern Parulas, two Black-and-white Warblers (one male, one female), two Magnolia Warblers (one male, one female), two Least Flycatchers, and one each White-eyed Vireo, Gray Catbird, Yellow-breasted Chat, and Blue-winged Warbler (female). Again, any and all of these birds had potential to to be encountered back in North America during migration or on their breeding grounds. Assuming we work the GOV site in future years, there's also the possibility for returns proving site fidelity in the pine savanna habitat.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center It was good to catch and band the Neotropical migrants, but the high point of the morning for the master bander--

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In close view (above) there's little question Yucatan Jays are members of the Corvidae--the same family as crows, ravens, magpies, and other jays--particularly because of the shape and color of the bill. The bill is black, and the upper mandible is stout and somewhat decurved--nicely adapted for an omnivorous diet that changes as plant and animal material becomes available on a seasonal basis. Seeds and beetles are staples. Many corvids also bear prominent crests--think again of the Blue Jay--and most have large-ish eyes and heads; the Yucatan Jay is no exception. (NOTE: First year Yucatan Jays have yellow bills; recent fledglings also have white heads and tail tips.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Blue color on the back and wings of Yucatan Jays (above)--as in other corvids--is not caused by pigment. Just like the metallic colors in a hummingbird's red throat and green back, any blue in the jay's feathers is structural, with tiny grooves and air bubbles absorbing and scattering light such that only blue wavelengths are seen. The black of the bird's head, of course, is melanin pigment.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Unlike many of its relatives, the Yucatan Jay lacks melanin in its legs (above); these are bright yellow with strong toes and long, curved, pale claws. One of the most interesting aspects of Yucatan Jays is they are cooperative breeders, with up to ten members of a flock helping a dominant adult pair raise its young. It is suspected the helper birds are related offspring from earlier broods. These younger birds undoubtedly gain valuable experience that maximizes their chances for success when eventually they become parents.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another bird we've found only in the pine savanna is Buff-bellied Hummingbird. We netted one of these on 11 March but caught several in previous years at Recia's Cashew Farm--although some were immatures with bellies of tan rather than the rich chestnut shown in the photo above.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Folks sometimes confuse Rufous-tailed Hummingbirds with Buff-bellied Hummingbirds (above) because both have red bills, green throats, and rusty-colored rectrices. Rufous-tails, however, always have have gray bellies.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Adult Buff-bellied Hummingbirds have brilliant green throats (above) in which the metallic color is strictly structural. The species is sexually monomorphic, with males and females looking alike externally.

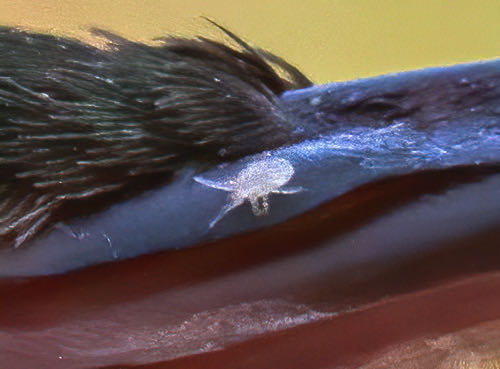

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another hummer (above) that often fools birders new to the Neotropics also showed up in our nets that first day in the pine savanna; it was a monomorphic species in which both sexes look very much like a female Ruby-throated Hummingbird. One glance at this bird's feeding apparatus rules out ruby-throat because our target species has an all-black bill, while the bird in hand had a pink lower mandible--making it a White-bellied Emerald. Note also the pure white throat of the bird in the photo, and the distinct contrast between green and white feathers at the base of the bill. What was REALLY interesting about this bird's bill didn't appear to us until we were processing our photo. Notice anything unusual in the image above? How about at the base of the upper mandible?

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A blow-up of the photo (above) reveals this White-bellied Emerald was carrying a hitchhiker--and if you look carefully you can find another one closer to the upper mandible's tip. These little white arachnids (count the eight legs!) are Flower Mites, nearly microscopic invertebrates that do indeed hitch rides from hummingbirds as they flit from one blossom to the next. Flower Mites are significant competitors with hummers for a plant's nectar; researchers found nectar production increased by up to 49% when the tiny mites--which can occur by the hundreds on a single blossom--were excluded. Because many Neotropical flowers last only one day, it behooves each Flower Mite to jump off a withering blossom and onto a hummer that can transfer it to a new flower by next morning. To complicate matters, some mites are monophagic (feeding on nectar from just one plant species), so their hummingbird air service needs to find just the right flower if the mite is to survive. Since Flower Mites compete with hummers for nectar and give nothing in return for free transportation, this is essentially a competing, parasitic relationship. (Incidentally, we were surprised the two mites were not dislodged from the White-bellied Emerald despite the bird's being in a mist net and lingerie bag. As they are known to do, the mites may have been hiding in the hummer's nostrils; there they would have been protected from being brushed off by net or bag.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Just as the team was surprised to see House Wrens in Belize, so were they confused by the bird in the photo above, thinking it looked an awful lot like Chipping Sparrows back home.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In the photo above is another "fooler" bird the team caught in the pine savanna Remembering their surprise over the presence of House Wrens and Chipping Sparrows, they first thought the new capture was a Great Crested Flycatcher--a reasonable thought considering the bird's gray throat and chest, lemon-yellow belly, and rusty wings and tail. When they looked for a crest, however, they found none and correctly concluded the bird must instead be a Dusky-capped Flycatcher, Myiarchus tuberculifer. That afternoon Ernesto led another of his productive Four O'Clock Walks, and after supper the team gathered for the daily summation and additional instruction about hummingbirds. And at the end of the evening meeting, they finally got an identity. Their nickname came from the unusual amount of precipitation Belize experienced in the "winter" of 2013-14 and that impacted upon the numbers and kinds of birds present in Crooked Tree Lagoon and elsewhere. Forevermore, the 2014 Belize team will be known uniquely and distinctively as the "High Waters."

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center DAY FIVE--12 March 2013 When we rose just before dawn 12 March, the words of Lodge owner Denver Gillett echoed in our ears: "A foggy morning means a hot day." There was definitely fog on the lagoon and--as we later found at our study site--there was fog (above) in the pine savanna. The day before had been plenty warm, so we loaded up our extra water bottles and pledged to remind each other to stay hydrated.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The birds must have thought it was hot, too, for despite deploying our full complement of ten mist nets we caught zero Ruby-throated Hummingbirds on our fourth day in the field, leaving our 2014 total at 12. The hummers were barely moving, feeding occasionally on Cashew nectar but mostly sitting motionless in the shade in low-growing trees. Other species were likewise lethargic and hard to come by, with our take for the day being just two Magnolia Warblers (both second-year males) and one Black-and-white Warbler (female, above), plus our first Yellow-rumped Warbler (female) and Ovenbird of unknown sex. The team had no difficulty identifying any of these Neotropical migrants and even recited the Ovenbird's educator-pleasing song of "Teacher, teacher, teacher."

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Two birds that seemed unperturbed by heat and humidity in the pine savanna simultaneously hit a mist net, possibly during a courtship chase. The first (above) was a gray individual with an oversized black crest that made its head look quite large. The bird was somewhat reminiscent of an Eastern Tufted Titmouse back home but had a noticeable decurved tip on its bill and a rose-colored blotch on its throat. 'Twas obviously a male Rose-throated Becard, Pachyramphus aglaiae, that--if we may make make a Human Value Judgment--was a bird with a real attitude. The photos above and below are two of about 50 we had to take to get the bird when it wasn't biting and tearing at our fingers with that (painfully) hooked bill.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center This species is easily identifiable in the field but creates a problem when birders aren't quite sure how to pronounce its name. Most folks say "bec-KARD," but Ernesto explained this isn't correct, citing the word's origins. Think instead of the nouns "wizard" (loosely translated as "largely wise") or "drunkard" (for one who is "drunk much"); then you'll remember the bird's name should be pronounced "BECK-erd," for its "big beak."

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The other bird looked just like the male Rose-throated Becard, except without a rosy patch and with brown or tan plumage in place of the gray. This was a female becard, whose nest is a foot-long bag with an entrance hole at the bottom. Her species has been placed in both the Cotingidae (Cotinga & Bellbird Family) and the Tyrannidae (Tyrant Flycatcher Family), but genetic evidence suggest becards actually belong in the Tityridae with such exotic (and largely unknown) species as the schiffornis, mourners, purpletufts, xenopsaris, and laniisomas. Rose-throated Becards are one Belizean species one can also see in southeastern Arizona and the lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas, where they occasionally breed.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Because of the heat in the pine savanna we ceased operations a little early, returned to the lodge for lunch and siestas, and at mid-afternoon boarded Capt. Leonard's canopied runabout (above) for a bird-watching boat ride on the lagoon. This craft, equipped with an outboard motor for speedy crossing, also had a quiet electric trolling motor that allowed much slower movement when there were things to see. Some of the time, Leonard cut all the engines and just allowed the boat to drift quietly.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Perhaps the most common waterbird this year at Crooked Tree was Neotropic Cormorant, Phalacrocorax brasilianus (above), formerly called Olivaceous Cormorant. Although they have webbed feet, cormorants climb easily in trees; the Neotropic Cormorant even perches on wires. Cormorants at Crooked Tree occur in flocks of up to 20 or so and dive for small fish, tadpoles, and frogs. Occasionally Neotropic Cormorants forage cooperatively, slapping their wings against the water as they drive potential prey into shallower water. The cormorant's semi-flexible, hooked bill (visible above) is an ideal tool for clamping down firmly on a squirming fish.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Also common around Crooked Tree were Great Blue Herons, Ardea herodius (above), at 54" tall the largest of the wading birds we observed on the lagoon this year. (The much-sought-after Jabiru--of which we have seen as many as 60 at one time in past years--simply wasn't present due to lagoon water levels still being so high. We did spot a few flying overhead during the 2014 expedition.) Some Great Blue Herons at Crooked Tree are breeding residents while others fly down from nesting grounds in North America.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Leonard let the boat drift so we could get an especially close view of the blood-red iris of our next wader: An adult Black-crowned Night Heron, Nycticorax nycticorax (above). The scientific name means "night raven" and refers to the bird's croaking nocturnal call. This species has a nearly worldwide distribution, nesting from southern Canada to southern Argentina in the New World, in parts of Europe, across most of non-desert Africa, and in the Middle East, India, and east Asia; Australia and Antarctica are the only continents that do not support breeding populations. Night herons typically roost by day, standing in shallow water at dusk and dawn while waiting for food items to move past. Their prey is anything they can grab with their strong, stout bills, from fish to crustaceans to small mammals and birds.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of the most common flowering plants in the lagoon was the Mayan Water Lily, Nymphaea ampla (above), a five-inch pristine white blossom with leaves that looked like a blade from a circular saw. Extracts from its flowers are reportedly hallucinogenic--a property that made the plant sacred to Mayan shamans and priests. Note also the pink Styrofoam-like object on the lily stem. This was the egg mass of an Apple Snail (Ampullariidae), which emerged during the night and deposited its eggs above the high water mark. When the eggs hatch, baby snails drop back into the water and the egg mass turns white.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We saw were hundreds of thousands of snail egg masses on emergent vegetation during the lagoon boat ride, all the better for Snail Kites, Rostrhamus sociabilis, such as the female in the photo above. As its name implies, the Snail Kite relishes adult Apple Snails it hunts when they're still out of the eater laying eggs; the kite's finely pointed hooked bill (see photo) enables the bird to pry the snail from its shell in short order. Adult male Snail Kite plumage is a uniform bluish-black; immatures resemble females but have streaked crowns. The species occurs in small numbers in the Florida Everglades, where it eats crayfish and small fish when Apple Snail pickings are slim.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As the sun settled lower in the eastern sky, Leonard leaned on his outboard motor for a speedy trip back to the Lodge--but not so fast he couldn't do a 180 when sharp-eyed Elaine noticed something of interest in the top of a big waterside shrub. When we doubled back Elaine pointed out a very large male Green Iguana, Iguana iguana, taking advantage of the last solar rays of the day. Males in this vegetarian species are heavily spined and have big dewlaps (throat pouches).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As the sun settled lower we could still see Neotropic Cormorants perched on dead limbs (above). Like the iguana, they were using final warm rays of the sun to dry their wings before settling down for the night. Because cormorants have poorly developed oil glands their feathers can become waterlogged--hence the spread-wing posture they often exhibit.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Being poets as well as naturalists, our citizen science group asked Leonard to stop the boat one more time for a look back at the sunset (above). Although he's seen this panorama hundreds of times through the years--Leonard was happy to cut the engines and join us in soaking up the view.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As the boat ride came to an end we could see lights coming on at the Lodge (above), a reminder it was almost time for supper, to be followed by the evening meeting and pleasant memories of our aquatic excursion on Crooked tree Lagoon.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center DAY SIX--13 March 2013 After two days each at the Reynolds Woodlot and the Pine Savanna study sites, we returned to the Hurricane Two Woodlot (HUR2, above) we first used last year. (See map.) This decision was driven in part because it was within walking distance of Crooked Tree Elementary School, home of Belize Audubon's Student Birding Club. This group is sponsored by Audubon ranger Derrick Hendy, who for the past several years has brought his young birders to learn first-hand about our research on Ruby-throated Hummingbirds and other Neotropical migrants. The kids always show up enthusiastic and interested, decked out in their school uniforms and exceedingly polite. Under Derrick's tutelage, some have become quite good at identifying various birds that live in and around Crooked Tree Village.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Hurricane Two Woodlot adjoins the FORMER Hurricane One Woodlot, our most productive study site during our first three years at Crooked Tree. Unfortunately, prior to our arrival last year a landowner defoliated the four-acre lot of Cashew trees and nearly everything else (above), clearing it for a home that has yet to be built. Obviously, clear-cutting made the locale useless for our research purposes. (Such is the risk of conducting long-term studies on private property--a problem we have also had among the Aloe Vera farms in Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica.) We hoped birds from HUR1 would simply move to adjoining HUR2, but our recapture records imply otherwise. Where they went we have no idea.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Anyway, our High Waters team got right to work on 13 March, deploying mist nets in HUR2 in the hope of having a few birds when the children arrived. At this our team was quite successful, allowing us to temporarily held a few species in lingerie bags for our big show-and-tell. We were pleased when the kids trooped in not only with Steve but also Dominique Lizama, Conservation Program Director for Belize Audubon and the person through whom we acquired our research permit for work within the Sanctuary. While Ernesto to worked hard running from one net to the next to extract any birds that might get caught, we called in our net watchers to gather around the banding table with the students. You could hear the excitement among young and old alike when we pulled the first surprise bird from our temporary holding bag.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Wow! We could hardly have asked for a better bird to start with than the brilliant blue and yellow one above. Its colors were breath-taking, to say the least, and eyes of students and adults alike were riveted on this little rainbow-in-the-hand as we showed it around.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When we held the bird in full view several kids waved their hands excitedly--indicating they wanted to tell us what the bird might be. One boy said "Euphonia," to which we replied he was correct--at least in part. After some hemming and hawing, another shier young man said "Yellow-throated Euphonia," and he was exactly correct. This was pretty impressive for a group of fourth through sixth graders.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Belize is home to three very similar blue and yellow euphonias. White-vented Euphonia occurs to the south but isn't present at Crooked Tree. The easiest way to differentiate males in the the other two species--our in-hand Yellow-throated Euphonia, Euphonia hirundinacea (above), and the the Scrub Euphonia--is the latter has a dark, blue-black throat. Females of all three species lack blue color entirely and are harder to identify.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although it wasn't as colorful as the euphonia, the kids were also enchanted when we pulled out an Ovenbird (above), especially when we explained this was a Neotropical migrant that spends only a few months in Belize before flying back to breeding grounds in far-off North America.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The euphonia and Ovenbird were interesting, but we saved our "most important" bird for last--an adult male Ruby-throated Hummingbird (above) with full red iridescent gorget. After all, it was because of ruby-throats were in Belize in the first place. The students knew this bird, too, even though it isn't a year-round resident, and were fully aware it was our target species on our Operation RubyThroat expeditions.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The kids looked on intently (above) as we showed them how we cut and form a hummingbird band--no easy task in the field--and how to make measurements of the little bird's weight and wing chord, tail and culmen lengths. Then we talked about how we once recaptured a ruby-throat in Belize we banded in a previous year, meaning this thumb-sized ball of fluff flew perhaps 1,500 miles north before returning that same distance to Crooked Tree. That concept led to a discussion of site fidelity and why it's important to protect habitat on both ends of a hummingbird's migratory path.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center With that we let a student release the banded ruby-throat (above), praised the kids for their attention, thanked them for allowing us the pleasure of doing field work in their own backyards, and sent them on their way back to school to study for upcoming national exams. We heard later, however, they only wanted to tell their teachers and fellow students about what they had seen in the field that morning.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The High Waters had a pretty eventful morning, too, marking their best day yet for capturing RTHU. Altogether they netted nine: Three adult males with fully red throats, two immature males with incomplete gorgets, and four females of indeterminate age. This brought the 2014 total to 21. They also brought in several other bandable Neotropical migrants, including two American Redstarts (second-year male, above, & second-year female), Magnolia Warbler (female), Black-and-white Warbler (male), Yellow-breasted Chat (unknown sex), and the Ovenbird (unknown sex) we showed the kids.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center HUR2 also turned out to be a pretty good spot for non-migrant birds such as the male Gray-headed Tanager, Eucometis penicillata (above). The female is somewhat paler with brownish upper-parts and a heavier hooked bill. This species often follows Army Ant swarms through the bush.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The team also brought in a little brown bird that has always impressed us with its name and the shape of its bill: the Plain Xenops, Xenops minutus (above), with a lower mandible that is boat-shaped. This bird is a member of the Furnariidae (Ovenbird Family), of which several species construct domed oven-like nest from clay. (Note that the Ovenbird that occurs in North America is a Wood Warbler in the Parulidae and is in no way related to the funariids.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Plain Xenops happens not to build a clay nest but places plant material in a large hole in a dead tree and lays its eggs. The stout bill (above) is adapted for digging beetle larvae from bark or rotten wood.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another common woodland species we caught at Crooked Tree was Greenish Melania, Myiopagis viridicata (above). This little member of the Tyrannidae (Tyrant Flycatcher Family) has a wide distribution from Mexico south to northern Argentina and occasionally winters in the southwestern U.S. Sexes are similar and since the yellow crown is typically not revealed the species is sometimes mistaken for a Tennessee Warbler.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The bird whose mouth-parts were by far the longest of any we caught in Belize was Ivory-billed Woodcreeper, Xiphorhynchus flavigaster (above). Like other members of the Woodcreeper Family (Dendrocolaptinae), this species superficially resembles woodpeckers and exhibits some of the same behaviors--including foraging in bark crevices for insects and other food items.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One characteristic the woodcreeper shares with woodpeckers is a stout tail in which the rachis (central shaft) is very stiff (above). This relatively inflexible tail provides support in bark-clinging birds, rather like the third leg of a tripod--with the other two tripod legs being the birds' actual feet.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Some time back Ernesto showed us an interesting trick that worked very well for the High Waters team this year. Prior to release you cover the woodcreeper's head with one hand and place its feet and body against a tree trunk. Loosen your grip and remove your hands and often the bird will remain motionless, allowing for an unposed photo like the one above.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Shortly after we showed the team our trick they caught a related species: Olivaceous Woodcreeper, Sittasomus griseicapillus (above). This individual was much smaller than its just-released cousin, with a far shorter bill. Olivaceous Woodcreeper has a wide distribution in Central and South America and sometime soon is likely to be split into separate species.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After a very productive and educational morning in the field, the team returned to the Lodge for lunch and quick showers, and to board the van for a trip to Belize Zoo. About 90 minutes south and west from Crooked Tree on the Western Highway, the Belize Zoo near Ladyville was established in 1993 as a "last ditch effort to provide a home for a collection of wild animals which had been used in making documentary films about tropical forests." These days the zoo is home to more than 150 animals representing 45 species--all native to Belize. The facility lays claim to being "the best little zoo in the world" and really is quite nice and worth a visit.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A favorite of zoo visitors are exhibits that contain big cats in natural habitats. Almost everyone is drawn to the fully grown Jaguar, Panthera onca (above), that calls the zoo home. This animal was rescued as a kitten and hand-reared at the zoo. Jaguars are the world's third-largest cat--only lions and tigers are bigger--but they are quite rare and seldom observed across much of their original range from the southwestern U.S. to southern Argentina.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Far more common and easily seen than Jaguars are White-nosed Coatis, Nasua narica (above), diurnal members of the Raccoon Family (Procyonidae). Rings on the coati's tail may be very pronounced or almost absent, and overall pelage color varies from dark gray to brown. The pig-like snout is used to root up everything from earthworms to scorpions to fallen fruit; being omnivorous, coatis also prey upon small rodents and birds, lizards, and crocodiles and their eggs. Solitary coatis are usually older males, while females and young males may form troops of up to two dozen individuals.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of the more unusual exhibits at the Belize Zoo includes albino White-nosed Coatis (above) whose pink noses look even more pig-like. One ought not be surprised to know these pure white coatis are named "Clorox" and "Blizzard."

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center DAY SEVEN--14 March 2013 Our sixth work day started with ominous skies in the east that followed waves of overnight downpours. Despite dark clouds, the High Waters knew we needed to take advantage of this final opportunity to capture and band Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. Buoyed by the previous day's success at HUR2, the team quickly erected mist nets there and sat back to wait on birds and the weather. It appeared the hummers were on the move--perhaps following last night's front or preceding the next one to come. Turns out we weren't disappointed, with the group netting six adult male Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, on immature male with incomplete gorget, and four females--11 in all for a total of 32 for the year. This was our best tally so far in 2014, but by about 9 a.m. those dark skies unloaded and we had to shut the nets in a hurry. What a disappointment when things were going so well.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The group also netted several other bandable birds, but with the rain coming down we had to dismantle the banding table and move everything to the van--including a backlog of birds still in lingerie bags (above). We strung these in the rear of the vehicle and drove a few hundred yards to Belize Audubon Nature Center, where Steve and staff allowed us to set up on an indoor table.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In the dry and in relative comfort (above)--especially compared to sitting on buckets and upturned flower pots--we banded the birds one-by-one. After banding, we placed each back in a holding bags so we could return them to HUR2 where they had been captured. None of this took very long, and were were at least out of the weather.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of the ruby-throats (above) we captured that rainy morning looked much different from the rest: Nearly two dozen of his gorget feathers were "in quill," i.e., still enclosed within the sheaths where they develop. Because the central-most gorget feathers were bronzish and probably old, we suspected this bird was an after-second-year individual that hatched prior to 2013.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our unusual male hummer notwithstanding, the most uncommon bird the group netted their last day was Louisiana Waterthrush, Parkesia motacilla (above), formerly Seiurus motacilla. This bird is one of the three brown and white Wood Warblers (Parulidae); the other two--Ovenbird and Northern Waterthrush--are much more abundant winter residents in Belize. It was fortuitous we took this bird to the Audubon Center for banding because Steve got one of his best looks ever; he told us at Crooked Tree they typically discover only one or two Louisiana Waterthrushes per year, if any, possibly because the species does not sing at all on the wintering grounds. By the way, our favorite little-known field mark for differentiating the two waterthrushes is the throat; Northern always has had brown speckles on the chin, while Louisiana (as shown above) has a pure white throat. In addition to the rainy day waterthrush we also caught and banded a male Black-and-white Warbler and a Yellow-breasted Chat.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When the precipitation stopped we went back to HUR2 to release the birds we had banded indoors and intended to re-open the nets for a few more hours. We could see another rain wave coming, however, so discretion overcame valor and we quickly shut down for the day, loading our damp equipment in the van for an early ride back to the Lodge. As might be expected, after one more cloudburst the skies cleared a bit, but by then it was too late for more field work.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center That afternoon the High Waters had time to start packing and to wander about for final photos and another Four O'Clock Walk. With all the rain overnight and during the morning, the pasture behind the Lodge was more flooded than before, bringing some birds even closer. We managed a good shot of one of those ever-present Northern Jacanas (above) standing at attention with its elongated toes hidden by the water. Based on size, this was probably an adult female; males are only half as big as their mates. Females are polyandrous, mating with several males who then assume incubation and chick-rearing duties.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Even an American Coot, Fulica americana (above), was swimming within reach of our 300mm telephoto lens, its red eye shining brightly in the afternoon sun. Most Belizean coots, AKA Mud Hens, migrate to North America, but there are also occasional summer records for Crooked Tree Lagoon. It is not clear whether these birds breed locally.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In an open-air garage beside the Lodge we had noticed the nest of a Ruddy Ground Dove, Columbina talpacoti, but until this day hadn't had opportunity to investigate. As we neared the nest two oversized chicks (above) exploded from it, flying a short distance before hunkering down on some exposed ironwork. We regretted causing what may have been a premature fledging, but the parents came right to the squabs and fed them away from the nest site. Thus, they were likely only a day away from departing the nest and everything probably ended up just fine.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As the High Waters came back in from their final afternoon walk there was another light rain shower--just enough water (above) for one of this resident Vermilion Flycatcher males to take a frenetic bath. Perched on a wire fence, he appeared to be doing his best to dampen and clean every feather on his body--one of the hallmarks of a healthy bird.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center DAY EIGHT--15 March 2013 The group's final morning at Crooked Tree began with a spectacular sunrise across the lagoon (above)--something the High Waters really didn't get to see during the week because we were always scurrying to our study sites. After a not-quite-so-early breakfast, the team checked out of their rooms, offered up hugs and fond farewells all around, and loaded luggage into the van. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center NOTE TO THE HIGH WATERS: Click on image above for a printable version. Since the Omega Group wasn't due to fly out until the next day, we decided to let trustworthy Leonard take the High Waters (above) to the airport while we went back to HUR2 for a little additional mist netting. After all, the preceding day--despite the rain--had been a banner morning for catching ruby-throats, so we wanted to continue with this success. Alas, it wasn't worth the effort. There were no Ruby-throated Hummingbirds to be seen on the study site, so we suspected they had moved through with yesterday's weather front and by now--like the High Waters--were preparing to depart the Yucatan Peninsula for their trans-Gulf flight to North America.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The only Neotropical migrants netted in four hours were a male Yellow Warbler and another Ovenbird, with the high point of the morning being a up-close look at a big-mouthed but unbandable Couch's Kingbird, Tyrannus couchii (above). Even in the hand this species is difficult to differentiate from the closely related Tropical Kingbird, T. melancholicus. In the field the two are separable by song, so it's fortunate Ernesto heard this particular bird sing just before it hit the mist net. Couch's Kingbird it was.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Since there was little bird movement, the Omega Group shut down at HUR2, returned to the Lodge, and began storing net poles, portable stools, mallets, and other equipment Bird's Eye View Lodge so graciously holds for us from year to year. We continued to operate the portable hummingbird traps in the Garden--as we had for a few hours nearly every day during the week--but despite successes during previous years the traps snared no Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in 2014. Thus, we closed the traps and with the rest of afternoon open decided to go out with camera for a long walk--something we never seem to have enough time for on our expeditions. First bird photographed: Mangrove Swallow, Tachycineta albilinea (above), perched on a wire just off the patio at the Lodge. Marked by white facial stripes and a white rump, these fast fliers patrol the property dawn to dusk, picking off various insects. The species occurs from Mexico to Panama.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Cattle Egrets are everywhere around Crooked Tree--the presence of fenced and free-roaming livestock undoubtedly is a factor--but we do not tire of observing this smallish, rather short-legged ardeid. What could be more photogenic than a little white bird side-saddling a horse while waiting for hooves to kick up insect prey?

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Cattle Egrets are not native to Belize or even the Western Hemisphere, but unlike European Starlings and House Sparrows were not introduced by misguided humans. It appears a flock of these birds got storm-blown from Africa to South America sometime about 1877 when they were first seen in Surinam. By 1953 they were breeding in Florida and since then have dispersed into nearly every corner of the U.S. Cattle Egrets seem to have found an "empty niche" in North America--following livestock in pastures--and their numbers appear not to significantly affect native bird species. They do, however, take huge numbers of large insects that might have negative impacts on agricultural crops.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Cattle Egrets seem fearless around livestock; the one above was in a slough filled with water up to the cow's shoulder. In return for the favor of stirring up grasshoppers, the egret sometimes plucks ticks and flies from horses and cattle.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Across the road from the grassy slough was an open pond with several old stumps. Atop one we saw a three-foot-long reptile with a big, toothy mouth (above). It was Morelet's Crocodile, Crocodylus moreletii, a formerly rare species increasing in number under protection provided by Crooked Tree Sanctuary. A rather shy species, Morelet's Crocodile is more common in creeks that feed the lagoon but is beginning to appear in open water--creating a risk to local spear-fishermen in pursuit of Tilapia. Young crocs eat fish and insects while adults--up to 14 feet long--can take down mammals such as coatis. In some areas they are known to prey on free-roaming cats, helping keep feral populations of these destructive creatures in check.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Because of our interest in corvids, we were pleased back in the pine savanna to actually hold a Yucatan Jay, but were likewise satisfied by our closest view ever of a Brown Jay, Psilorhinus morio (above). The individual in our photo is an adult; first-year immatures have yellow bills, legs, and eye rings. Brown Jays occur in flocks during the non-breding season but are not quite as social as Yucatan Jays; cooperative chick-rearing occurs less often. Although Brown Jays occasionally forage on the ground, they spend most of their time in trees, consuming insects, lizards, ripened fruit, and even flower nectar. Brown Jays occur sporadically in the southern Rio Grande Valley but are far more common along the Caribbean Slope from Mexico south to Costa Rica. We've also seen them in dry forests in Guanacaste on the western side of Costa Rica.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Why does the Plain Chachalaca (above) cross the road? Only the chachalaca knows for sure. Chachalacas, Ortalis vetula, are long-legged gallinaceous birds in the Cracidae (the family that also includes guans and curassows). Often arboreal, they are essentially herbivorous, feeding on seeds, fruit, leaves, and flowers. This is another Neotropical species that occurs in south Texas.