|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

11-19 Nov 2017 & 20-28-Jan 2018 Come be part of a real |

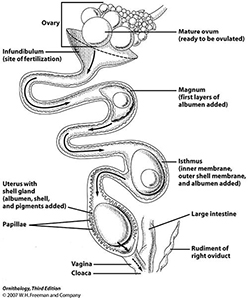

BIRD EGGS (Part 2): NOTE: After we posted "This Week at Hilton Pond" installment #653 about the way bird ova are fertilized and hard-shelled eggs form in the female's oviduct, we received several e-mail inquiries about how embryos actually develop after laying. (We also received a couple of notes insisting that bunnies really DO bring eggs.) As follow-up, our current photo essay below deals with that topic, from the time a bird egg is laid until it hatches. Among wild female birds at Hilton Pond Center and elsewhere, a rush of hormones--typically in spring--causes dormant ova (unfertilized eggs) to begin maturing in the bird's ovaries; there, each receives a deposit of fat- and protein-rich yellow yolk. (Click on the image below right to view a larger version of a female bird's reproductive tract, courtesy W.H Freeman and Co.)

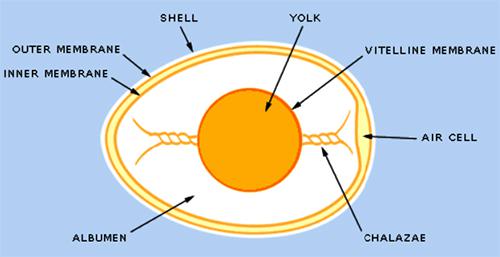

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A bird's egg is a completely self-contained unit, requiring nothing from the parents except protection and heat. The eggshell itself--surprisingly strong for its weight and thickness--is made almost entirely of crystals of calcium carbonate (CaCO3); it is permeable, meaning air and moisture can pass through its pores (above). The shell also has a outer coating (bloom or cuticle); semi-permeable, it helps repel dust and bacteria while also allowing passage of gases and some liquids. Although fish and amphibians are obligated to lay eggs in more or less aqueous environments, bird and reptile eggs MUST be deposited in dry locales lest water seep in through cuticle and shell, eventually suffocating or drowning the developing embryo.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Immediately inside the eggshell (see drawing above) and surrounding the albumen are two thin but tough membranes made mostly of keratin protein. These, too, are semi-permeable and help keep out bacteria. Between the two membranes at the egg's "base" is an air cell that increases in size as moisture and carbon dioxide depart through the eggshell. This air cell fills with oxygen that is then available when the embryo begins breathing on its own just prior to hatch. Within the egg-white are the chalazae, two twisted strands of mucin (a protein) that hold the yolk and early embryo in place at egg center--even when the egg is turned during incubation. This allows for optimal exposure to external heat and to water-laden, energy-rich albumen inside the egg.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In most birds, incubation does not begin until the final egg of a clutch has been laid; thus, observers should not be alarmed when a songbird begins laying but appears to pay no attention to her nest. She and her mate are probably nearby keeping an eye on things and may (or may not) defend an incomplete clutch against nest predators. Since Carolina Chickadees at Hilton Pond Center historically have laid 5-8 eggs per clutch, just three in the photo above suggests this particular cavity-nesting pair still had a ways to go.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As noted, deferring incubation until a clutch is complete is typical of the majority of bird species. Such behavior yields a synchronous hatch because embryonic development does not begin until heat is applied, such as when a hot-bodied parent bird--usually the female--begins sitting tight (American Robin, above). Synchronous hatch would seem advantageous because all chicks will be the same age and should mature at about the same rate. (Even a day or two of age difference leads to younger, smaller nestlings being unable to compete with older siblings for food and attention. In raptorial birds that employ an asynchronous hatch, younger siblings are sometimes eaten by older brothers and sisters that survive to carry on their parents' genes.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Once incubation starts, eggs must be kept at fairly constant high temperature--somewhere in the range of 100°-105° F for most birds--allowing embryonic development to progress at a more or less constant rate. If an incubating parent is away from a nest for extended periods--especially on cold days--egg temperature may drop so low the embryo actually dies; this is one reason why nesting too early during a chilly, wet spring often leads to failure of a pair's first clutch. (On the bright side, an early nesting pair does get a chance to try again if the first attempt fails for whatever reason.) Hilton Pond Center's cavity-nesting birds such as Eastern Bluebirds (four-egg clutch in photo above) have an apparent advantage in that their eggs are more protected from the elements, allowing them in spring to get a head start on species that nest in the open.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Incubation is greatly facilitated by a brood patch that develops in many bird species, particularly in females. Hormonal activity in spring may cause the female's belly feathers to fall out--or she may pluck them herself--resulting in a bare expanse of skin. Since feathers retain a female bird's body temperature, naked skin makes for much better heat transmission to her eggs. What is even more remarkable about the brood patch is it becomes highly vascularized (with more capillaries available to bring body heat from the adult bird's core) AND it becomes edematous (with heat-moderating fluids accumulating beneath the skin). In essence, the brood patch--as shown above in our photo of a female House Finch--becomes a natural hot water bottle well-adapted for keeping eggs at optimum temperature! (NOTE: Although females in many species develop brood patches, the bare patch seldom appears in male birds; notable exceptions are woodpeckers and some flycatchers in which sexes share daytime incubation duties. For Mourning Doves, females incubate at night while males handle the chore during daylight hours. In some species male birds without brood patches can be observed sitting on nests while the female is away, but they may merely be protecting eggs from heat loss rather than adding any body heat.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The length of time it takes a bird embryo to develop from fertilization to hatching date varies greatly from species to species. Among songbirds, oddly enough, bigger eggs from bigger birds don't take predictably longer than eggs laid by smaller birds. The Carolina Chickadee female mentioned previously incubates her clutch for about 13 days, while much larger American Robins at Hilton Pond Center have sat for 12-14 days; American Crows go for 18 days, compared to 13 for diminutive Blue-gray Gnatcatchers (photo above, with both sexes cooperatively nest-building before taking turns incubating). Among non-passerine examples, Wild Turkey hens incubate for 28 days, a Killdeer pair shares duties for about 24 days, and the two tiny eggs of a female Ruby-throated Hummingbird take 14-16 days to hatch. (It's worth noting that high or low ambient temperatures may add or subtract a day or two.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Just for kicks, guess how long a New Zealand Kiwi (skeleton above, with egg inside) needs to incubate its relatively enormous egg? (Answer: About 70-80 days--supposedly so long because of the Kiwi's low body temperature rather than egg size.) Incidentally, we wondered if the length of a bird's incubation period might correlate with whether its chicks hatch out naked and helpless (altricial) or downy and ready to run (precocial), with eggs of the latter possibly taking longer to develop. We were unable to find anything in the literature supporting or refuting our hypothesis and welcome your insights about this at INFO.

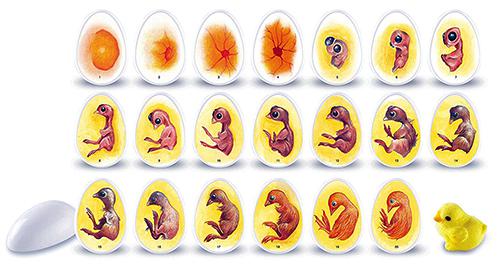

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Despite popular belief, an incubating adult bird does not sit uninterrupted for the duration of the incubation period. Instead, the incubator fidgets and moves, stands upon occasion to turn and sort the eggs (insuring all surfaces receive equal amounts of heat), and sometimes flies off temporarily to forage and/or void fecal matter. In some species an attentive male will feed a female on the nest, as shown by the Northern Cardinals above. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Click on image above to open a larger version in a new browser window Because of wide variabilities in incubation times we can't say what is happening inside the egg on any given day for a particular bird species at Hilton Pond Center, but all bird embryos follow essentially the same developmental progression. This phenomenon has been studied best by poultry farmers, who need to know exactly what is happening day-to-day in a domestic chicken's egg. The illustration above shows just how fast things happen as soon as incubation begins, with a chicken embryo's full 21-day developmental sequence as follows. (Modified from a poster by Cobb-Vantress Inc., a poultry research company.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center All bird embryos mature in the general sequence described above, except altricial songbird chicks hatch out featherless, blind, and incapable of thermoregulation; their parent(s) must keep these helpless nestlings warm while also finding food to fuel ever-growing appetites--a chancy balancing act on cold spring mornings. Precocial open-eyed hatchlings such as baby Wild Turkeys might be better off because they are covered by down, maintain an even body temperature, and run about seeking their own food. However, downy nestlings like those of Black Vultures (above), owls, hawks, and egrets are still relatively weak, don't ambulate well, and must be fed and tended by their parents--sometimes for up to two months after hatching. Obviously there are many variations on the interrelated themes of incubation and bird embryo development.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Regardless of a given species' reproductive strategy, we find the laying of a hard-shelled bird egg and what happens inside it to be one of nature's great wonders. And it happens every spring at Hilton Pond Center to Carolina Wrens (above) and 25 other wild bird species known to have nested right here on our 11-acre enclave in the Carolina Piedmont. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Don't forget to scroll down for Nature Notes & Photos,

Checks can be sent to Hilton Pond Center at: All contributions are tax-deductible on your |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

Comments or questions about this week's installment? Send an E-mail to INFO. (Be sure to scroll down for a tally of birds banded/recaptured during the period, plus other nature notes.) |

JUST ANNOUNCED!

JUST ANNOUNCED!

Please report your

Please report your