HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND

8-14 March 2003

Installment #164---Visitor #

Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND

8-14 March 2003

Installment #164---Visitor #

Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week

|

AMAZING WOODPECKER TONGUES Woodpeckers are remarkable creatures with numerous adaptations and behaviors very different from those of other birds at Hilton Pond Center. Straight, strong, chisel-like bills help them tear into dead wood after grubs or to build nesting cavities. Zygodactyl feet--two toes in front and two in back--allow woodpeckers to grip tightly on vertical bark surfaces, and stiff tail feathers and legs form a tripod that braces against a tree as the bird hammers away. The woodpecker brain is oriented tightly within the skull such that it cannot move far, avoiding concussions. And the woodpecker's highly efficient neck muscles produce on-going series of rapid movements--and that repetitive rat-a-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat. In our opinion, however, the most phenomenal aspect of these birds is one we seldom see in the wild: their amazing woodpecker tongues.

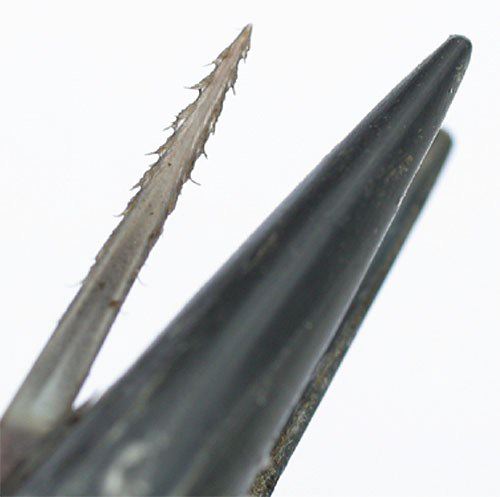

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Woodpeckers peck on wood in a variety of ways. When starting a nest hole, they hammer their way in and twist their heads from side to side, flinging wood chips left and right and out of the cavity. During courtship, the male looks for a particularly resonant snag or--to the chagrin of late-sleeping humans--a gutter downspout; on these structures the woodpecker merely drums without penetrating, making a species-specific noise that announces his presence to any female that might be within earshot. It is while grub-hunting that the incredible capabilities of the woodpecker tongue really come into play. Galleries formed in trees by wood-boring beetle larvae are often quite extensive. Located just beneath the outer layer of wood, these shallow tunnels can stretch up and down the trunk for several inches--even feet--depending on the insect species. When the woodpecker's bill breaches an insect gallery, it extends its tongue and probes around. If it locates grubs, the woodpecker skewers the prey with its tongue, the tip of which is hard and sharply pointed. After the tip penetrates the soft body of a larval insect, tiny rear-facing barbs grab hold as the woodpecker withdraws its tongue with the succulent food item impaled thereon (see photo of tongue and bill at top of page).

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center In order to navigate the insect gallery, a woodpecker's tongue must be longer than its bill; in the case of the Red-bellied Woodpecker (male, two photos above), the tongue extends at least THREE times the bill length. In some woodpeckers the tongue is so long it forks in the throat, goes below the base of the jaw, and wraps behind and over the top of the head, where the forks rejoin and insert in the bird's right nostril (below left) or around the eye socket. Within the entire length of woodpecker's tongue lies the "hyoid apparatus," a linear series of tiny bones sheathed in muscles and soft tissue; the ultra-thin hyoid bones, which fold up accordion-like along part of their length, are visible in the photo below right. When the woodpecker wants to stick out its tongue, it contracts branchiomandibularis muscles near the base of the hyoid apparatus. This forces the hyoid bones forward within their sheath and propels the tongue out of the bill. Relaxing the muscles allows the tongue to shorten and brings it back inside. The woodpecker's tongue also contains paired longitudinal muscles that move it side to side as the bird probes for food. It is believed that woodpecker tongues are especially sensitive to touch--an adaptation that helps greatly in detecting unseen insects within dead wood.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Not all the six species of woodpeckers seen at Hilton Pond have barbed tongues or feeding behaviors like those described above. A Yellow-bellied Sapsucker's tongue, for example, is relatively short and edged with feathery bristles that, through capillary action, help the bird lap up sweet sap that oozes from rows of quarter-inch holes it drills in trees. (It's worth mentioning that the nectar-lapping tongue of a hummingbird is structured and works in ways like that of a sapsucker, except that the tip of the hummer's tongue is split and rolls into a shallow spoon-like shape.) Interestingly, the tongue in a newly hatched woodpecker is quite short, which makes it much easier for parent birds to stick food items into the hungry nestling's gaping mouth.

Amazing woodpecker tongue, indeed! Photo of Red-bellied Woodpecker skull courtesy Stanlee Miller, Clemson University NOTE: Be sure to scroll down for an account of all birds banded or recaptured during the week, as well as some other interesting nature notes. "This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use the on-line Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to "This Week at Hilton Pond," just send us an E-mail with Subscribe in the subject line. Please be sure to configure your spam filter to accept E-mails from hiltonpond.org. |

|

Make direct donations on-line through

Network for Good: |

|

|

LIKE TO SHOP ON-LINE?

Donate a portion of your purchase price from 500+ top on-line stores via iGive: |

|

|

Use your PayPal account

to make direct donations: |

|

|

Participate in the

Just visit the site for

Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project by clicking on the link above |

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS WEEK * = New species for 2003

NOTABLE RECAPTURES (with original banding date, sex, and current age) Dark-eyed Junco (1) 02/03/02--after 2nd year male Northern Cardinal (3) 06/15/01--3rd year male 07/30/01--3rd year female 07/29/02--2nd year female Eastern Towhee (1) 08/08/02--2nd year female White-throated Sparrow (4) 01/09/99--after 5th year unknown 11/06/00--4th year unknown 11/06/01--3rd year unknown 11/26/01--after 2nd year unknown Red-bellied Woodpecker (1) 04/19/02--3rd year male (photos above)

VAGRANT HUMMINGBIRDS None banded this week. |

WEEKLY BANDING TOTAL YEARLY BANDING TOTAL (2003) 15 species 373 individuals BANDING GRAND TOTAL (since 28 June 1982) 123 species 42,487 individuals

SIGHTINGS OF INTEREST --One male Wood Duck attacked an interloper on Hilton Pond on 13 Mar and violently chased it under water before retiring to sit atop a nearby nestbox occupied by an incubating female. |

Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week

|

Up to Top of Page Back to This Week at Hilton Pond Center Current Weather Conditions at Hilton Pond Center |

post questions for The Piedmont Naturalist |

Join the |

Search Engine for |

|

|