|

|

|||

|

|

|||

()Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week)

|

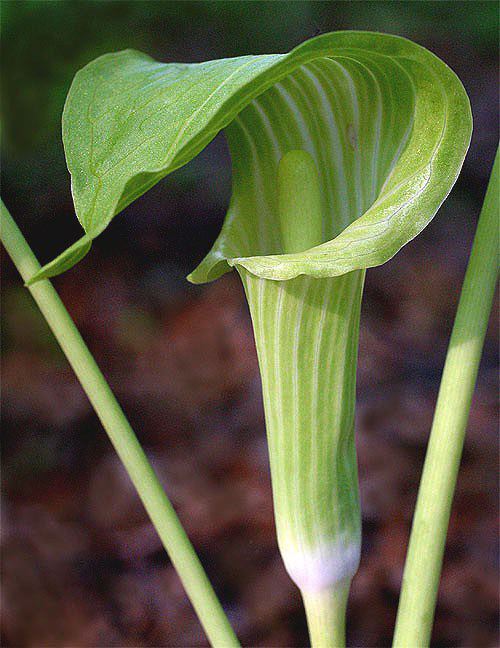

IS THAT "JACK" IN THE PULPIT? One of the few disappointments about the land at Hilton Pond Center is that it was heavily farmed for a hundred years, perhaps longer. Previous tenants planted row crops such as corn and cotton, and at various times in the past century cattle grazed freely across the 11-acre tract. As a result, nearly all our native wildflowers were exterminated and have just begun to recover in the 21 years since the site has been allowed to "return to nature." The first returnees, of course, have been those whose seeds are wind-dispersed or that are eaten and later deposited--along with a little guano--by free-roaming birds and small mammals. Through the years we're tried to supplement this natural dispersal by planting--with varying success--a few native wildflowers to enhance natural diversity. This week one of those efforts paid off when a species with an unusual lifestyle came into bloom outside the office window at the Center's old farmhouse.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Eight years ago we planted a half-dozen specimens of Jack-in-the-Pulpit beneath some dogwoods and a towering Southern Red Oak. Two of the jacks didn't make it through the first winter, and the other four seemed to limp along from year to year, sometimes flowering and sometimes not. Eventually two more transplants died, and we had just about decided this was one species that probably wasn't adapted to our poor, depleted soils. The inflorescence of a Jack- in-the-Pulpit is indeed unusual. It arises just above the soil level along with one or two thrice-divided compound leaves (above left). The bloom consists of a deep, cylindrical spathe--the "pulpit"--that bears alternating stripes of lighter and darker green; in some individuals there's a little purple thrown in (below right). Lifting the flap at the top of the spathe reveals our slender and round-headed friend "Jack," known better to botanists as the spadix. At the base of the spadix will be one of two things: thread- like male flowers that yield yellow pollen, OR tiny green berry-like structures that are actually female flowers (pictured at below left with the withered spadix still attached after the dried spathe has been removed). Thus, a Jack- in-the- Pulpit plant is either male OR female, leading us to believe that at least some of the plants should be known as "Jill-in-the-Pulpit." Usually a jack that makes male flowers has only one main leaf (right), while female plants have two.

The specific taxonomy of Jack-in-the Pulpit, a member of the Arum Family (Araceae), is rather up in the air. One of Jack-in-the-Pulpit's closest relatives is the rarely encountered Green Dragon, A. dracontium, which occurs across the Carolina Piedmont; Like other arums, Jack-in-the-Pulpit has a heavy rootstock that stores food and contains buds that produce next year's leaves and flower. This corm is laden with so much oxalic acid that jacks are considered to be poisonous plants. When raw root and stems are ingested by humans, mucous membranes in the mouth are sometimes burned severely, and all parts of the plant can cause swelling of the tongue and severe gastric distress. Curiously, during poor growing years, an individual jack that has served as a female may revert to making only male flowers, while under especially good conditions long-time males suddenly become berry-bearing females. This potential for intermittent sex changes--which can occur several times over a plant's 20-plus-year lifespan--leaves us perplexed over the proper common name for our blooming Arisaema triphyllum. Ever mindful of being politically correct, at Hilton Pond Center we've decided to play it safe and henceforth refer to all our individual plants as "Jack-AND/OR-Jill-in-the-Pulpit."

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

Red berry photo © Oklahoma Biological Survey POSTSCRIPT: Patrick Polchies--a Maliseet Indian of the Kingscear First Nation who lives along the St. John River in New Brunswick, Canada--tells us his ancestors did indeed "use the roots of Jack-in-the-Pulpit, but certainly not for food! They would gather large quantities of the plant's roots along with wild onions, mash them together, and dump the mixture in a stream or a brook. This would stun fish in the waterway, allowing them to be collected easily at the surface by people downsteam of the dumping spot. I am unsure if fish actually have to ingest the root/onion mix or if the oxalic acid is stong enough to simply stun them. Sounds like an easy and effective way to get a meal!" All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The public is invited to register for the annual conference of  held this year in Rock Hill SC. Comments or questions about this week's installment? Please send an E-mail message to INFO.

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond." (Please see Support if you'd like to make a gift of your own. You can also contribute by ordering an Operation RubyThroat T-shirt.)

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written & photographed You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use our on-line Hilton Pond Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to |

|

|

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS WEEK * = New species for 2003 WEEKLY BANDING TOTAL 8 species 8 individuals YEARLY BANDING TOTAL (2003) 30 species 505 individuals BANDING GRAND TOTAL (since 28 June 1982) 123 species 42,619 individuals NOTABLE RECAPTURES THIS WEEK (with original banding date, sex, and current age) Carolina Chickadee (1) 03/29/02--after 2nd year male Northern Cardinal (5) 11/17/95--9th year male 01/17/99--after 5th year female 04/23/00--after 4th year female 08/13/01--3rd year male 07/29/02--2nd year male Tufted Titmouse (1) 04/18/02--after 2nd year male Carolina Wren (1) 06/30/01--3rd year male |

Kentucky Warbler Kentucky WarblerThis adult female captured this week was only the 18th of her species banded at Hilton Pond Center since 1982. Kentuckys breed uncommonly across the Carolinas. --A major windstorm (some TV meteorologists called it a "gust front" with 60-70 mph winds) barrelled through Hilton Pond Center on the afternoon of 2 May, blowing down most of the remaining "widow makers" (dangling limbs) broken off during last December's devastating ice storm. As might be expected, the biggest branches fell on mist nets; several net poles were bent and rendered useless but fortunately none of the much more expensive nets were seriously damaged. |

|

Up to Top of Page Back to This Week at Hilton Pond Center Current Weather Conditions at Hilton Pond Center |

You can also post questions for The Piedmont Naturalist |

Join the |

Search Engine for |

|

|