|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

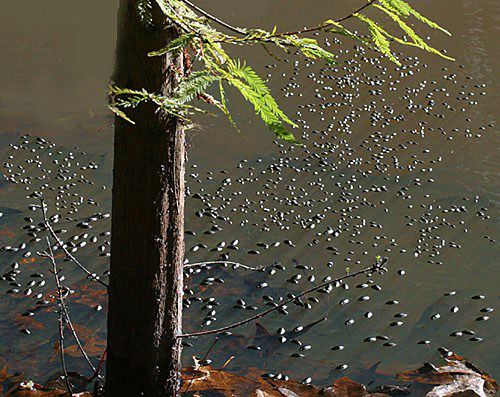

WHIRLIGIGS Our office window at Hilton Pond Center looks out over Hilton Pond itself--not a bad view when we're stuck at the computer instead of walking the trails. On windless days, we're often alerted to the arrival of a Wood Duck or a Great Blue Heron when it disturbs the water and sends concentric ripples radiating away from the point where it touched down. On one quiet morning this week we noticed continuous agitation on the far side of the pond at the spillway. We figured a school of Mosquito Fish must be working the shallows in pursuit of insect larvae, but--just in case--we grabbed the digital camera and went out to investigate. Right where the trail starts across the dam that forms Hilton Pond, we easily spotted beneath a Bald Cypress sapling what actually was disturbing the water: A huge and highly animated assemblage of Whirligig Beetles.  The Whirligigs must have been having a convention at Hilton Pond, for this was by far the largest cluster of aquatic insects we had ever seen--perhaps 400 or so swimming madly about, bouncing off each other like bumper cars at an amusement park. Although some observers report Whirligig movements are choreographed like a flock of birds that turns in unison, we saw no such coordination; this beetle herd was about as good a demonstration of chaos as one could imagine. There were two distinct sizes of Whirligigs, one about three-eighths of an inch long and hanging closer to shore, the other about half that size and further out. Since all beetles go through complete metamorphosis--egg to larva to pupa to adult--and are full grown when they finally emerge, Most Whirligig species are somewhat flattened top to bottom and dark brownish- black; the ones at Hilton Pond looked rather like fat watermelon seeds bobbing about on the water's surface. Because of their speed and the randomness of their swimming, it wasn't possible to observe the beetles' actual means of locomotion in their natural habitat, so we went back to the lab to fetch a long-handled dip net to collect a few of the Whirligigs for closer examination. Using nets to catch individual insects often results in failure, especially with fast-flying critters such as flies and wasps. The mass of Whirligig presented no such problem, however, and with one swoop of the net we caught a dozen or so that we transferred to a gallon jar half-filled with water. When we dumped them in, the beetles immediately dived to the bottom of the jar. Through the glass we could see a large air bubble at the posterior tip of each beetle's abdomen, undoubtedly a reserve that allowed the insect to breathe underwater. We also observed that each beetle had two very elongated forelegs that it tucked in as it swam, thus helping with streamlining. The other two pairs of legs were short and flat and appeared to do most of the work propelling the Whirligigs. Occasionally when a beetle slowed down, it extended its long forelegs and somehow grabbed onto the smooth inner surface of the jar. One of the Whirligigs even placed its forelegs akimbo over its elytra (hard wing covers) when it stopped swimming (above left).

Wanting to learn more about Whirligigs, we carefully scooped up an individual beetle from the jar and placed it on a dead leaf, where it sat still long enough for us to focus with our macro lens. The resulting photo (above) reveals several interesting things. For one, the tip of the Whirligig's abdomen was edged with a white fringe that probably serves as a point of attachment for the diving bubble we observed through the glass. Next, the joints between the elytra and where they meet the rest of the exoskeleton were nearly seamless--another streamlining adaptation. And last, the head of the beetle also bore a few fine white-tipped "hairs"; we suspect these are tactile sensors that supplement the work of the Whirligig's nearly vestigial antennae. After "posing" momentarily for photos, our captive beetle used its elongated forelegs to drag itself along on the leaf. It was like a fish out of water, however, and forward progress on land was infinitely slower that what it could accomplish in its aquatic element. With due care, we rolled the beetle on its back temporarily for a closer view of its six legs, which fit snugly and perfectly into depressions on the underside of the abdomen. We were surprised to find the middle legs in particular look a lot like flattened lobster claws (below).

Although we associate Whirligig Beetles with aquatic habitats, they are also masters of the air, using their membranous wings to fly from place to place. This is a useful skill, since sometimes a pond or puddle they inhabit dries up during drought. Once the Whirligig has established residence in a pond or slow-moving stream, it trolls about, using surface tension to keep its body only half submerged. From this position it whiles away the hours looking for smaller insects upon which to dine, including mosquito larvae that might be missed by those Mosquito Fish with which it shares Hilton Pond. Since Whirligigs live at the interface between air and water, they have a unique problem in needing to look upward for mates or potential predators and--at the same time-- downward where food items lurk. Amazingly, a Whirligig Beetle has FOUR compound eyes, two flattened ones on the upper part of its head (red arrow at below right), and two rather bulbous ones on the underside (green arrow). The bottom pair is also visible in the photo of the beetle's ventral surface (above).

Whirligig Beetles are placed in their own family (Gyrinidae), and the 50 or so species in this country are divided mainly into two groups, Dineutus spp. (the bigger ones) or Gyrinus spp. (the smaller). We suspect both genera were represented by the horde of Whirligigs churning the water this week on Hilton Pond, but we'll never know for sure which species they might be. Seems the only way to identify Whirligigs conclusively is using a hand lens to examine the male genitalia, and our beetles were whirling WAY too fast for us to see those particular private parts. POSTSCRIPT: Aquatic entomologist Dr. John H. Epler of Wakulla Springs, Florida read this week's installment and determined that the Whirligig Beetle illustrated here is a female Dineutus carolinus. He also mentioned that although Dineutus Whirligigs do smell like apples, their Gyrinus relatives "have a positively rank odor." Comments or questions about this week's installment? NOTE: Be sure to scroll down for an account of all birds banded or recaptured during the week, as well as some other interesting nature notes. "This Week at Hilton Pond" is written & photographed You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use the on-line Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to "This Week at Hilton Pond," just send us an E-mail with SUBSCRIBE in the Subject line. Please be sure to configure your spam filter to accept E-mails from hiltonpond.org. |

|

Make direct donations on-line through

Network for Good: |

|

|

LIKE TO SHOP ON-LINE?

Donate a portion of your purchase price from 500 top on-line stores via iGive: |

|

|

Use your PayPal account to make direct donations:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS WEEK: * = New species for 2003 WEEKLY BANDING TOTAL 15 species 26 individuals

YEARLY BANDING TOTAL (2003) 56 species 947 individuals

BANDING GRAND TOTAL (since 28 June 1982) 123 species 43,061 individuals |

Cape May Warbler This fall migrant is fairly nondescript. Its light breast streaking, yellow- green rump, and at least a hint of yellow behind the ear help make the identification.

NOTABLE RECAPTURES THIS WEEK (with original banding date, sex, and current age) None

VAGRANT HUMMINGBIRDS None this week

OTHER SIGHTINGS OF INTEREST --The Ruby-throated Hummingbird banded on 3 Oct was only the 34th captured for that month out of 2,810 total banded since 1984 at Hilton Pond Center. The latest was on 18 Oct 1986, so the season may not quite be over yet. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center |

Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week

|

|

|

Up to Top of Page Current Weather Conditions at Hilton Pond Center |

post questions for The Piedmont Naturalist |

Join the |

Search Engine for |

|

|