|

|

|||

|

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND

13-31 March 2011 INSTALLMENT #506---Visitor # (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center DIMINUTIVE DOWNY: After nearly a month and a half studying Ruby-throated Hummingbirds on their Central American wintering grounds, we returned home this week to the Carolina Piedmont and Hilton Pond Center. Our backyard thermometer read 84 degrees--almost as warm as it was in Belize--but we were pretty sure this late winter "heat wave" soon would disappear. Even though it took a few days to get re-accustomed to watching White-throated Sparrows and Purple Finches rather than Jabiru storks and Long-tailed Manakins, we were quickly back to banding our usual winter resident birds. We were happy to see Pine Siskins were still consuming our thistle seeds; any more we captured would simply the record number banded so far this winter season.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We catch most of our winter finches--siskins, Purple and House Finches, and American Goldfinches--in a custom-made trap baited with sunflower seeds relished by all four species. Several other species also will enter the trap's one-way tunnels, allowing us to snare everything from Pine Warblers to Northern Cardinals to Carolina Chickadees. One day this week the feeder even caught a tuxedo-clad bird familiar to most feeder watchers across the U.S. and Canada--a black and white male Downy Woodpecker with red on its nape (above).

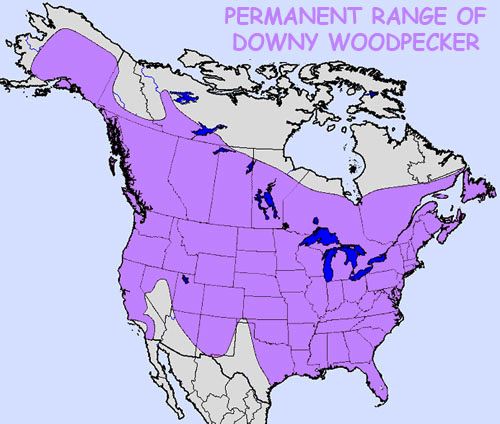

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Downy Woodpeckers are the smallest and third-most widely distributed of 22 extant woodpeckers in the U.S. and Canada. (To be honest we'd never tallied all our woodpecker species and were surprised to find there were 22 of them--23 before the Ivory-billed went extinct!) Downy Woodpeckers live year-round somewhere in every state except Hawaii (see map above), and they occur throughout Canada except the extreme Arctic regions. About the only places you won't find Downy Woodpeckers in the contiguous U.S. are West Texas and desert areas of the Southwest. For whatever reason, downies don't regularly get into Mexico--as do Hairy Woodpeckers (the downy's slightly larger relative) and the Northern Flicker (which has the widest range of all our woodpeckers). Downy Woodpeckers occur in wooded habitats that include deciduous trees potential nesting cavities; in dryer regions they tend to hang out along streams and river bottoms. Here at Hilton Pond Center Downy Woodpeckers are by far the most commonly encountered member of the Picidae (Woodpecker Family), with 174 banded locally since 1982. Compare that to results for our five other picids: Red-bellied Woodpecker (80), Yellow-bellied Sapsucker (43), Northern Flicker (35), Hairy Woodpecker (24), and Pileated Woodpecker (just one). Cornell's Project FeederWatch lists Downy Woodpeckers as the fourth-most-commonly reported backyard species in North America.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Recently fledged Downy Woodpeckers look a bit different than adults. Their overall plumage tends to be fluffier and a tad brownish and they begin molting some of their flight feathers shortly after leaving the nest. Of special interest is that many nestling Downy Woodpeckers have red on their head, but on the crown rather than the nape as in adult males; this red is more extensive in nestling/fledgling males (above). We speculate the function of the red crown in young birds is to make them more visible to parents peering down at them in the darkness of the nest cavity.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Observers sometimes have trouble differentiating Downy Woodpeckers from the quite similar Hairy Woodpecker, but there are a few diagnostic characteristics. For one, the diminutive Downy is only about 5.75" long from bill tip to end of tail, while the Hairy is 7.5" long. (That's roughly the size difference between a White-throated Sparrow and a noticeably larger Northern Cardinal.) You should also consider bill size; in a Downy the bill is half the length of the head or shorter, while in a Hairy the mandibles are more than half the head length. In the photo above of a female Downy Woodpecker the bill length is distorted somewhat by the camera angle; note her complete lack of red head feathers.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although all Downy Woodpeckers, Picoides pubescens, have black bars on their white outer tail feathers (underside view above), this character is not quite as diagnostic as many observers believe; a very small percentage of Hairy Woodpeckers, Picoides villosus, also have black tail spots, but the chance of encountering one of these birds is quite small. Despite the two species' external similarities, some ornithologists believe they are not very closely related and should be split into separate genera. Note, by the way, that the Downy's central tail feathers--aka rectrices--are long and quite stiff, providing a sort of tripod support when the bird's feet are gripping a tree trunk. (The rectrices in the photo above are quite worn, indicating they are old and have become abraded by rubbing against tree trunks all winter.)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center And speaking of the feet of Downy Woodpeckers (above), these appendages are zygodactyl--meaning there are two toes in front and two in back. (Most birds are anisodactyl, with three front toes and a rear-facing toe, or hallux.) The woodpecker's outside toe has rotated back toward the hallux and has become the longest digit, a configuration that allows a woodpecker--in conjunction with its long decurved claws--to get a better grip on a vertical tree trunk.

Downy and Hairy Woodpeckers can also be differentiated by tree foraging behavior: The smaller Downy tends to feed on twigs and smaller branches of vines, shrubs, and trees (as depicted John James Audubon's painting at the top of this page that includes a Crossvine), while Hairy Woodpeckers seek insects on main limbs and trunks. Downy Woodpeckers also feed on berries and seeds and come readily to suet feeders in winter (banded male, above). The species even pecks on goldenrod galls and in winter forages in mixed flocks with chickadees, nuthatches, kinglets, and titmice. There is some indication local food resources are partitioned according to sex, with males feeding on thinner twigs in the canopy and females gravitating toward thicker branches in the understory.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We've heard some observers say Downy Woodpeckers have pronounced wing bars, but they do not. Wing bars are typically created when the tips of covert and lesser covert feathers are paler than the rest of the feathers. In a Downy, however, the spotted appearance of its wing is caused by actual spots (above), distributed evenly along the lead edges of the primary and secondary feathers. (Note, however, that tips of the secondary coverts DO bear white spots, as do bases of the primary coverts.) White spots are much less prominent on wings in the species' western and northwestern populations. Downy Woodpeckers can make their nest cavities in limbs as small as 3"-4" in diameter, while the Hairy requires a somewhat larger branch. The Downy occasionally nests in a main trunk, as shown in the rendering at right from Illustrations of the Nests and Eggs of Birds of Ohio (1879-1886). Downy Woodpeckers occasionally use nest boxes erected for bluebirds, but pairs seem to prefer excavating their own nest sites. (Be sure to use a 1.25" opening--Eastern Bluebird houses have a 1.5" hole--and add fresh wood chips to the bottom of nest boxes intended for Downy Woodpeckers.) The species also roosts in boxes during the colder months--a good reason to maintain those artificial cavities year-round. Incidentally, the longevity record for a free-flying downy is a banded male in California that lived at least 11 years and 11 months.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The male Downy Woodpecker we caught this week at Hilton Pond Center was more docile than most, so we were able to take lots of in-hand photos. Sometimes individuals are quite aggressive and peck away at our fingers and knuckles, causing numerous little puncture wounds and considerable pain. (Their claws are also very sharp and inflict serious scratches if we're not careful.) It's fortunate, as shown in the photo above, a Downy's upper mandible is slightly chisel-shaped rather than sharply pointed. A stiletto-like bill would cause much more damage to our hands, but it also would be more likely to wear or break as the woodpecker pecks wood. The photos above and at left reveal one final note you might not know about this week's spotlight species: Irises of the adult are a deep plum red--a colorful touch as this diminutive Downy Woodpecker watches us watch it at our feeders year-round at Hilton Pond Center.

|

Both species excavate their own nest holes and usually use them only for one year, after which the cavity can be taken over by any number of species including bluebirds, titmice, chickadees, and nuthatches. One Downy Woodpecker nest that successfully fledged four youngsters one year at Hilton Pond Center was occupied in successive springs by Eastern Bluebirds, Carolina Chickadees, and House Wrens. Among downies both parents share all duties, including incubation, brooding, feeding chicks, and nest sanitation. It's worth mentioning that male Downy Woodpeckers develop an "incubation patch"--an area of featherless skin on the belly that becomes vascularized and edematous and transmits body heat very efficiently to eggs and chicks. In the vast majority of bird species, only the female develops an incubation patch; woodpeckers are one exception.

Both species excavate their own nest holes and usually use them only for one year, after which the cavity can be taken over by any number of species including bluebirds, titmice, chickadees, and nuthatches. One Downy Woodpecker nest that successfully fledged four youngsters one year at Hilton Pond Center was occupied in successive springs by Eastern Bluebirds, Carolina Chickadees, and House Wrens. Among downies both parents share all duties, including incubation, brooding, feeding chicks, and nest sanitation. It's worth mentioning that male Downy Woodpeckers develop an "incubation patch"--an area of featherless skin on the belly that becomes vascularized and edematous and transmits body heat very efficiently to eggs and chicks. In the vast majority of bird species, only the female develops an incubation patch; woodpeckers are one exception.

Right now we can hear a Downy pecking on an oak branch not far from our office window, but it is a loud, repetitive sound that indicates he's drumming for a mate rather than drilling for insects.

Right now we can hear a Downy pecking on an oak branch not far from our office window, but it is a loud, repetitive sound that indicates he's drumming for a mate rather than drilling for insects.