|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

FALL MIGRATION BEGINS, SORT OF When we viewed the TV weather forecast on the evening of 8 September, we saw those two magic words that never fail to excite birders--and banders--in autumn: Cold Front! All across the eastern U.S. bird enthusiasts began salivating at the prospect a cold wave of air would bring a hot wave of warblers down from breeding areas in Canada and the northern states. You see, there's nothing like a cold front and a strong tailwind to encourage pending migrants to start moving south toward wintering grounds in the Neotropics. That night we went to bed early with the intention of rising just before dawn to unfurl our mist nets, all in the hope of seeing which early migrants would become candidates for lightweight aluminum bands they could carry--possibly toward some other bander in Central or South America. We hadn't run nets at Hilton Pond Center the past several weeks for a variety of legitimate reasons, so we really were excited when an internal alarm went off at 6 a.m. on 9 September and we rose to deploy nets. We have lots of established net lanes--more than 40--at various locations along the 2.8 miles of trails that meander our 11-acre property, but decided to run just what we call the "house nets." This array of nine 42-foot-long mist nets is in close proximity to the old farmhouse that serves as the Center's office. We had some desk duties and family affairs to attend to while operating mist nets that day and didn't want to have to wander too far for regular net checks.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The first bird activity we see at Hilton Pond at dawn or just before is almost always families of North Cardinals that come in to glean spilled sunflower seed from the ground beneath our many feeders. Thus, we weren't surprised when the first bird we caught on the morning after the cold front was an immature male cardinal (above) just starting to replace brown feathers he acquired as a nestling. A black mask was beginning to appear around the base of his bill, pinfeathers on his cheeks were opening into red feathers, and his crest was taking on an adult appearance. There was no question he was an immature bird, indicated for sure by the dark color of his upper and lower mandibles. We banded this young Northern Cardinal--undoubtedly a locally produced bird and NOT a migrant--and went out to check the nets again.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center What did we snare this time around? You guessed it: Another Northern Cardinal, but this was an adult female with mature plumage and a bill of deep orange (above). Her overall coloring was brownish tinged with red and only a hint of that dark mask of an adult male. Again, she was not a migrant but undoubtedly a resident who knew her way around the feeders but didn't see the almost-invisible mist net that caught her.

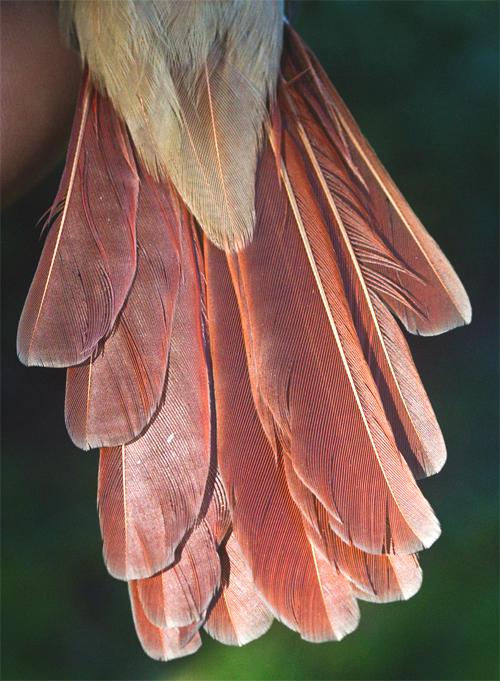

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Like the immature cardinal, this adult female was exchanging old feathers for new. Her body molt was essentially complete, but her tail (above)--normally comprised of feathers of approximately the same length--had outer feathers only half the length of centrals. Most birds molt the inner feather pair first and then stagger feather loss and replacement toward the outside of the tail. This allows for continued flight stabilization that wouldn't be possible if all the feathers were molted at once.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center On the same net check but in a different net was an adult male Northern Cardinal in all his scarlet glory. He, too, showed some tail molt and facial pinfeathers (above), and his back feathers had brownish tips that will wear off by next spring, bringing him into full breeding plumage just in time to attract attention of local females. We continued to capture Northern Cardinals on 9 September, ending up by dusk with the surprising total of TWENTY new ones--plus a couple that were already banded. We doubt any of these were migrants. Instead they were either locals or an example of what we call the "fall shuffle"--a post-breeding dispersal of young birds leaving their parents and natal sites as they explore more distant spots. Among other things, the fall shuffle--typical of most bird species--helps diminish competition for local resources among close relatives and expands the gene pool by diminishing potential for inbreeding.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We caught another crested bird on 9 September, but this one was far less colorful than the Northern Cardinals. This particular bird had more formal attire of gray and white with a touch of black, it being an Eastern Tufted Titmouse (above). Titmice are also non-migratory residents around Hilton Pond and this individual already carried a leg band; we first caught it as a recent fledgling back on 19 May so it will be interesting to see if it remains in the area and is recaptured throughout the winter. (Titmice are sexually monomorphic with males and females looking alike externally; we won't be able to determine its sex unless we capture it next spring in breeding condition.) At feeders Eastern Tufted Titmice always appear to have big eyes--a function of the black eye ring that shows nicely in the photo above. The relatively short, straight bill is adapted for everything from cracking sunflower seeds to gleaning insects from bark crevices.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Other non-migratory members of the Titmouse Family (Paridae) also hit our nets on 9 September, those being two Carolina Chickadees (above). Like their titmouse relatives, this species is also sexually monomorphic and has that non-specialized short black bill that in our experience is adapted for painfully pinching cuticles of bird banders, particularly on days when cold temperatures make a bander's fingers most sensitive to pain. Even here in the Carolina Piedmont backyard birders--especially northern transplants--often misidentify Carolina Chickadees as Black-capped Chickadees. While it's true both species have black caps, the Carolina Chickadee is a low elevation bird with a more southerly distribution while the black-capped occurs only in the mountains or further north. At some locales in the Appalachians the two species have overlapping ranges and sometimes interbreed, which really complicates field identification.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We weren't surprised our mist nets--and our sunflower seed traps--captured a few House Finches on the morning after the cold front. After all, HOFI are the most commonly handled birds at Hilton Pond Center with exactly 9,009 of them crossing the banding table since 1982. We didn't actually band any new House Finches on 9 September but did recapture a few local individuals we'd handled earlier in the summer. The one above was banded in July when it was a completely brown fledgling whose sex could not be determined via plumage. The nice thing about recapturing it was we now knew it's actually a "him," based on raspberry feathers replacing those immature brown ones. Most of this year's young males have begun acquiring at least a few red feathers by now, although we won't feel confident calling a completely brown House Finch a female until the first of November. (NOTE: 'Way back in the 1980s, foreign encounters of several House Finches banded at the Center indicated all our HOFI were MIGRANTS from the northeastern U.S. The species has done so well at expanding its range, however, it is now one of the most common BREEDING birds in the Carolina Piedmont.)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center As our mist netting continued on 9 September we caught additional non-migrant resident birds, the next being a Carolina Wren (above). This species is also sexually monomorphic, and it likely was an adult bird; we couldn't find any signs of immature feathers, and its breast was the rich light brown of an adult. Carolina Wrens--the state bird of South Carolina--are pretty much ubiquitous in the Palmetto State, breeding from the Mountain Province to the Coastal Plain. The long, slightly decurved bill is nicely adapted for prying insects and other invertebrates from tight quarters and for carrying sticks the males use to build dummy nests--and one nest the female will choose to use. These nests can appear, seemingly overnight, in just about any available cavity from bluebird houses to buckets to old boots hanging from a tool shed hook. Historically, our biggest problem with wrens at Hilton Pond Center comes when they end up nesting in an automobile grill or the spare tire on our utility trailer, thus curtailing our driving or keeping us from hauling trash.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center And speaking of long bills on Carolina Wrens, our next species netted was a long-billed immature female Downy Woodpecker (above) who mistook our hands for dead pieces of lumber as we tried to extricate her from the mesh. The sharp chisel-like tips of her stout bill made a series of tiny holes in our knuckles and--to make matters worse--her powerful bark-clinging claws left numerous scratches on our fingers. (No complaints here, just observations. Such are the accepted perils in the life of a bird bander.) We knew this was a female because she was all black and white; by this time of year a male would have a red spot on the back of his head. Perhaps the most interesting woodpecker trait visible in the photo above is the tongue--quite muscular and with a hard tip armed with tiny rear-facing barbs. When this woodpecker detects a beetle larva in a tree, she makes a hole big enough to insert her tongue, skewers the grub, and lets the barbs dig in as she pulls another tasty snack from its gallery. Downy Woodpeckers are yet another resident species; so far on 9 September none of those anticipated northern migrants had been captured after riding the cold front to Hilton Pond Center.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center That said, our next mist-netted species was a little yellow bird that 30 years ago around Hilton Pond likely WOULD have been a fall migrant. It was a second-year female American Goldfinch who was undergoing molt and replacing her heavily worn and faded first-year feathers with new ones. This was surprising because the bird was molting AND had a well-defined "brood patch"--a naked belly laden with fluid and blood vessels. (Such a bare spot lets an incubating or brooding female transfer body heat with much greater efficiency to eggs or nestlings and is a sure sign she is a local breeder.) We were surprised because breeding and heavy molting don't typically occur simultaneously--both are energy-intensive activities--but may occur in female American Goldfinches because they breed so late in the year; perhaps they need to begin feather replacement before cold weather arrives despite their motherly duties. (AMGO are likely the last songbirds to nest in the Carolinas; they apparently delay breeding until late summer to take advantage of ripening wild thistle seeds they feed their young.) One other thing: We mentioned that 30 years ago we would have considered an American Goldfinch banded at the Center in September to be an early migrant; that's because back then we had no evidence of local breeding for the species. We suspect goldfinches have been expanding--or at least solidifying--their breeding populations throughout the Piedmont Region. Historically they bred uncommonly in most of the Carolinas away from the coast, nesting instead across the northern tier of states and in southern Canada. It's hard to explain this change in breeding range, but American Goldfinches--which nest primarily in edge vegetation--may be one of those species that benefited from abandonment of old southern farms that went through natural succession.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center All the species mentioned so far have been local breeders, but with the arrival of the next species in our mist nets we were finally beginning to think it--a Red-eyed Vireo--demonstrated the cold front really WAS bringing in migrants. Problem is, Red-eyed Vireos breed throughout the Carolinas as well much further north into Canada, so there was no proof this individual wasn't a local. We did know it was an adult--its red eye would have been brownish in a first-year immature--and it did have a great deal of yellow fat stored in the furcular (wishbone) area at the base of its throat. Although this massive fat deposit--an excellent source of energy--certainly indicated the vireo was migrating, we still had no way of knowing if it was a local or came from afar on its way to South America's Amazon Basin. (NOTE: Red-eyed Vireos are sexually monomorphic but males can be somewhat larger. Unfortunately the wing chord measure on this particular bird fell in in the overlap between males and females, so we were unable to determine its sex.)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Like Red-eyed Vireos, American Redstarts have a wide breeding range that covers much of North America, so the one above that hit our Hilton Pond mist nets on 9 September also could have been either a local or a long-distance migrant from Canada. Redstarts are Wood Warblers (Parulidae) whose most obvious field marks are big color spots at the base of the tail and in the wing and flank. Adult males are black with salmon-colored spots while females are gray-green with yellow. Young males like the one we caught (above) resemble females but usually show much darker yellow or orange. The well-pronounced broken eye ring is a further aid to identification. Other than Yellow-rumped warblers that overwinter locally, American Redstarts are our most commonly banded Wood Warblers with a total of 419 since 1982. (In case you're wondering, Magnolia Warblers are close behind at #3 with 410 banded.) If you're keeping track, so far that was Northern Cardinal, Eastern Tufted Titmouse, Carolina Chickadee, House Finch, Carolina Wren, Downy Woodpecker, American Goldfinch, Red-eyed Vireo, and American Redstart we caught on 9 September. All were good birds to see and capture and photograph and band, but they weren't very good evidence for that highly anticipated wave of fall migrants that was supposed to be riding the southbound cold front.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Finally, from our office window at late morning we could see one net contained a smallish bird with a head and back of such distinctive color we knew what it was even without binoculars. The bird's dorsum was an unusual greenish-yellow that we find difficult to describe and almost as hard to photograph accurately; suffice it so say once you've seen it you'll know exactly what we mean and you'll never forget the hue. It was unmistakably a Chestnut-sided Warbler in non-breeding plumage. This species--alpha code CSWA--breeds in the northeastern U.S. and down the Appalachians but NOT in the Carolina Piedmont, so it was the first true fall migrant to appear in our nets on 9 September. Based on pointy tail feathers we determined it was immature, and with no sign of any chestnut on its flanks it was almost certainly a young female. We're quite fond of Chestnut-sided Warblers--they were one of the first warbler species we were able to identify in our first ornithology course at Mountain Lake Biological Station in Virginia--plus we just like the way CSWA look in all plumages. They're not the most common Wood Warbler migrant at Hilton Pond--only 80 banded in 32 years--but we like them nonetheless.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Lest there be any doubt fall migration was underway at Hilton Pond, one need only look at the photo above of the next bird banded on 9 September. It was another Wood Warbler, although its lack of yellow and its overall brown appearance leads many beginning birders to call it a thrush or a sparrow. No, this was a Northern Waterthrush, one of the ground-nesting not-so-arboreal-feeding warblers that breed barely into the continental U.S. and mainly in Canada and as far north as Alaska. Curiously, closely related Louisiana Waterthrushes do breed in the South--we've never seen a nest at Hilton Pond but have caught recent fledglings and females with brood patches--but Northern Waterthrushes only pass through in migration that in autumn leads them toward wintering sites in the Neotropics. (NOTE: We've banded NOWA in Costa Rica and Belize during our hummingbird expeditions to those Central American countries, so maybe someday we'll encounter a Hilton Pond waterthrush down there.)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Northern Waterthrushes and Louisiana Waterthrushes look a little alike, but LOWA are a bit bigger and chunkier and have whiter superciliary lines (i.e, above the eye). In our judgment, the best differentiating characteristic for these two species is the throat, which in LOWA is clear but in NOWA (as shown above) is streaked right to the base of the lower mandible. So that's it. A cold front on the night of 8 September, and a full day of netting on the following day. Did the front bring lots of southbound migrants? Apparently not, but it brought some, and it certainly gave us the initiative to run mist nets all day so we could capture a lot on local birds that needed bands. We'll continue to unfurl our nets over the next few days to see if there's any residual effect from the cold front. Even if there isn't we're certain there will be another front on the way, barrelling down from Canada with a wave of warblers and other fall migrants that delight the eye and give us cause to ponder the whole incredible phenomenon of fall migration. Hope you like our photos of residents and a few migrants; more are sure to come as migration continues. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center This week we're celebrating executive director Bill Hilton Jr.'s upcoming 66th birthday with a special funding opportunity through Causes. Please help out if you can! All contributions are tax-deductible |

|---|

The Piedmont Naturalist, Volume 1 (1986)--long out-of-print--has been re-published by author Bill Hilton Jr. as an e-Book downloadable to read on your iPad, iPhone, Nook, Kindle, or desktop computer. Click on the image at left for information about ordering. All proceeds benefit education, research, and conservation work of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. The Piedmont Naturalist, Volume 1 (1986)--long out-of-print--has been re-published by author Bill Hilton Jr. as an e-Book downloadable to read on your iPad, iPhone, Nook, Kindle, or desktop computer. Click on the image at left for information about ordering. All proceeds benefit education, research, and conservation work of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. |

|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

Comments or questions about this week's installment? Send an E-mail to INFO. (Be sure to scroll down for a tally of birds banded/recaptured during the period, plus other nature notes.) |

Click on image at right for live Web cam of Hilton Pond,

plus daily weather summary

Transmission of weather data from Hilton Pond Center via WeatherSnoop for Mac.

|

--SEARCH OUR SITE-- For a free on-line subscription to "This Week at Hilton Pond," send us an |

|

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond" with students, teachers, and the general public. Please see Support or look below if you'd like to make a gift of your own.

|

If you enjoy "This Week at Hilton Pond," please help support Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. It's painless, and YOU can make a difference! (Just CLICK on a logo below or send a check if you like; see Support for address.) |

|

Make credit card donations on-line via Network for Good: |

|

Use your PayPal account to make direct donations: |

|

If you like shopping on-line please become a member of iGive, through which 950+ on-line stores from Amazon to Lands' End and even iTunes donate a percentage of your purchase price to support Hilton Pond Center.  Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase through them earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause! Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase through them earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause! Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. |

|

BIRDS BANDED THIS WEEK at HILTON POND CENTER 1-9 September 2012 |

|

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS WEEK: * = New species for 2012 WEEKLY BANDING TOTAL: 11 species 54 individuals 2012 BANDING TOTAL: 31-YEAR BANDING GRAND TOTAL: (since 28 June 1982, during which time 171 species have been observed on or over the property) 126 species (31-yr avg = 66.6) 57,873 individuals (31-yr avg = 1,866) NOTABLE RECAPTURES THIS WEEK: Northern Cardinal (1) Carolina Wren (1) |

OTHER NATURE NOTES: --Various species of Goldenrod (Solidago spp.) are starting their annual fall bloom. We encourage folks to wade into a local patch to see what they can find. Few habitats are busier or more diverse busier than a field of Goldenrod in early autumn. Remember, Goldenrod's sticky insect-transported pollen does NOT cause fall hay fever; powdery wind-blown pollen from grasses and Ragweed DOES. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center |

Please report your sightings of

Please report your sightings of