|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

BLUE JAYS, Cyanocitta cristata: Weather at Hilton Pond Center has been very mild thus far in the winter of 2012-13, with above-normal temperatures and below-average rainfall prevailing. Our always-anticipated cold-weather birds have not really arrived, giving us pitiful banding results for seasonal migrants 1 November through 15 January: Three Purple Finches, one Dark-eyed Junco, one Pine Siskin, three White-throated Sparrows, and two American Goldfinches. Were it not for trapping 81 House Finches--some of which actually might be local residents--we'd have almost nothing to show for our banding efforts over the past ten weeks or so. In last week's installment we speculated about why last year's banding total was our lowest ever; some of the same reasons may help explain this winter's paucity of birds. We're not doing anything particularly different this year--save one thing: Along with the usual black sunflower and thistle seeds in feeders, we've been ground-scattering a mix of millet, milo, and cracked corn. What has been missing is another additive we've always used in the past--shell corn--dry whole kernels relished by some of the larger birds (and squirrels). This week at Hilton Pond Center we finally added shell corn to our mid-winter scatter mix and, believe it or not, within five minutes we had trapped our first Blue Jay in two years!

All text, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We're always pleased to have a Blue Jay in-hand, if only because it brings back happy memories. Before we made the leap to conducting field research on hummingbirds, Blue Jays were our study species during grad school days at the University of Minnesota. There, mostly at the university's Cedar Creek Natural History Area north of the Twin Cities, we spent three very long, very cold, very dark winters--and some buggy springs and summers--working on the behavioral ecology of Blue Jays. In one of those strokes of serendipity that often allows success in field projects, we met soon bird bander Jean Vesall, who also was interested in Blue Jays AND happened to live in a subdivision that adjoined Cedar Creek.

All text, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center On top of nest-hunting (and subsequent banding of Blue Jay nestlings during the breeding season), we spent a lot of time year-round trapping and mist netting jays. Each received the usual numbered aluminum band issued by the federal Bird Banding Laboratory, but we also gave each bird three color bands in a unique combination that allowed us to identify each bird without recapture--simply by looking at its legs through binoculars or a spotting scope. (In the photo above, one about-to-fledge jay shows a yellow-over-orange combination on its right leg while its two less-adventurous nestmates hunker down.) In all we color-marked more than 1,500 nestlings, fledglings, and adults during the three-year study and discovered numerous pairs of Blue Jays maintained year-round bonds; those that did got a much earlier start on breeding each spring. Established pairs also frequently showed strong site fidelity, often nesting in the very same site or close to it year to year. And curiously, the most successful nests were those built within the subdivision, especially on human structures such as houses--or on limbs hanging over dog pens! (We suspect these human-related locales served to minimize predation by egg-robbers such as crows, snakes, and squirrels.) We uncovered many more interesting factoids about Blue Jays during those grad school days--certainly enough to give us more admiration and respect for the species than admitted to by many backyard birders.

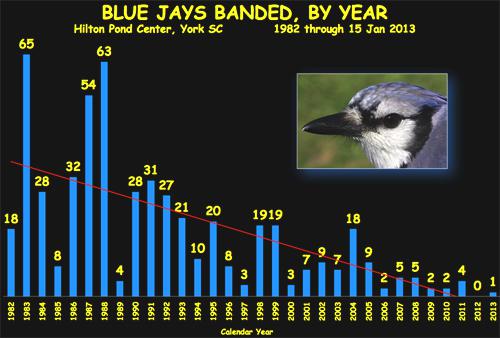

All text, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When we returned from Minnesota in 1982 to establish what is now Hilton Pond Center we hoped to continue our work with Blue Jays and caught 208 of them locally during our first seven years here (see chart above). We dutifully color-banded these individuals--some of which most certainly were winter migrants--but only found a few nests. Alas, in the mid-1990s the Blue Jay population crashed--in part because a neighboring farmer clear-cut a 70-acre Loblolly Pine forest and then because West Nile Virus took a major toll on jays and other corvids across the eastern U.S. It's a good thing we had already shifted to Ruby-throated Hummingbirds as our species of interest; in the past 15 years we've averaged less than a dozen or so Blue Jays per calendar year and in 2012 ended up with none--hardly enough jays to derive any new knowledge of scientific significance. With all this in mind, one can understand our delight this week at the Center's first in-hand Blue Jay since January 2011. For old-time's sake, we took a lot of photos of this bird and include them below in an effort to give folks better appreciation for an under-appreciated species.

All text, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Blue Jays are sizable birds, bigger than an American Robin and smaller than Mourning Dove. Tail tip to bill tip they measure 9"-12", with a substantial wingspan of 13"-17". Individuals from Canada can be up to 25% larger than those that breed in Gulf Coast states. (Some taxonomists recognize up to four subspecies of Blue Jays, based on size, plumage, and distribution.) Since northern populations often migrate, the Carolina Piedmont plays host to migrants as well as non-migratory residents--providing a mix of "big" and "small" individuals at the winter feeder. Blue Jays are sexually monomorphic, i.e., males and females look alike externally. Despite extensive measurements on our Minnesota jays we were never able to find a way to sex them based on mass or length of wing, tail, leg or bill. The only sure way to sex a Blue Jay (short of surgery) is during the breeding season when females develop a prominent brood patch--a bare patch of edematous and vascularized skin on the belly that enhances transfer of body heat to eggs and chicks.

All text, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although sexing Blue Jays is very difficult, it's often possible to determine the age of an individual jay--or at least to say whether it's "immature" or an "adult." Younger birds retain their juvenal feathers--particularly alulars and secondary coverts. In the image above, the main flight feathers (white-edged primaries at the bottom of the photo) are overlapped by bluish-brown primary coverts; similarly colored alular feathers at the bend of the wing overlap some of the primary coverts. Compare all these with the white-tipped, blue secondary coverts that are heavily barred with black. This noticeable contrast between primary and secondary coverts is the sign of a younger bird, meaning the jay we caught this week (in January) is in its second year; that is, it hatched sometime during the summer of 2012. Older Blue Jays (after second year) never have brownish primary coverts or alulars; these feathers are blue and almost always have some degree of barring. In many jays this plumage difference allows you through binoculars to age a mid-winter bird at your backyard feeder.

All text, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Blue Jay's genus name, Cyanocitta, comes from Latin and Greek words meaning "blue" and "chattering bird," while the species epithet cristata refers to the jay's crest--a structure that often lies flat. These terms are mostly accurate, except for the blue part, for in actuality Blue Jays appear but are not "blue"--they are black and white and gray. We say this because Blue Jays--as well as Indigo Buntings, Blue Grosbeaks, Black-throated Blue Warblers, and Eastern Bluebirds--do not get their color from blue pigment. Their blue appearance is caused by tiny air bubbles and grooves in feathers that overlay the black pigment, melanin. When light strikes the bubbles and grooves it is scattered such that the observer only perceives blue wavelengths--the same phenomenon that makes the black of space look blue when sunlight is scattered by Earth's atmosphere. Thus, the blue color of a Blue Jay is structural in nature rather than pigmental, unlike the way a Northern Cardinal appears red because its feathers contain red pigment. One of the remarkable things about Blue Jays is how many different shades of "blue" they exhibit--as in the photo above of the bird's back and crossed wings--indicating there are many different configurations of air bubbles and grooves overlaying the melanin. Where melanin pigment is completely absent, of course, the feathers appear white.

All text, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center And while we're on the topic of color, although from a distance the Blue Jay appears to have a large black eye, its iris is actually rich, deep chestnut--or at least appears to be. As with its plumage, the jay's iris color comes from scattering of light, this time because of varying concentrations of melanin crystals that occur in various structures within the eye. (From this you may conclude correctly that if you have blue or hazel or green eyes they aren't really hazel, green, or blue. No to burst the poet's bubble, but we humans all have black eyes--unless we're true albinos who lack melanin completely.)

All text, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center It's interesting that the whole time we had this week's Blue Jay in hand--including measurements, banding, and photography--it never disgorged that shell corn in its craw. We could see two kernels for sure, but based upon the distended crop (see photo above), there were probably more than that, and our captive wasn't about to give up ANY of them. Blue Jays are hearty eaters--one reason why some folks don't like them much--and a small flock of jays can clean out a bird feeder in short order. They're pretty much omnivorous, eating lots of insects during warm weather and then shifting to fruits, nuts, and seeds as seasons dictate. Blue Jays have what we believe is an undeserved reputation for robbing other birds' nests of eggs and chicks--several studies showed their stomachs contained less than one per cent of these items--but they sometimes do it and occasionally even take an adult bird. Much more important is this information: The Blue Jay often caches seeds, burying them and then forgetting where some of them lie.

All text, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center And we don't just mean they cache sunflower seeds, either. In Minnesota we frequently saw Blue Jays gather two, three, or even four red oak acorns in their crops and fly considerable distances before alighting to eat. They almost never consumed all four nuts, choosing instead to scratch out a small hole in the ground in which to hoard one or more acorn. These jays thereby did the mighty oak a mighty favor, transporting its acorns much further than they would be taken by a terrestrial mammal such as squirrel or chipmunk. We could go on and on about Blue Jays, but next time you see one at your backyard feeder, try to refrain from tapping on the glass and shooing it away. Jays may seem boisterous and gluttonous, but this common backyard species eats much larger insect pests than most birds can consume, it helps expand North American forests, and it entertains us with its highly social behavior. Even its vocalizations are pleasing to the ear, from its familiar "jay-jay-jay" call to its very accurate imitation of a Red-shouldered Hawk. If you happen to be in the Carolinas, spend some time just watching these colorful corvids, happy in the knowledge you didn't have to endure three very long, very cold, very dark winters with us in the wilds of Minnesota studying the behavioral ecology of Blue Jays!

All text, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center All contributions are tax-deductible on your |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

Comments or questions about this week's installment? Send an E-mail to INFO. (Be sure to scroll down for a tally of birds banded/recaptured during the period, plus other nature notes.) |

Click on image at right for live Web cam of Hilton Pond,

plus daily weather summary

Transmission of weather data from Hilton Pond Center via WeatherSnoop for Mac.

|

--SEARCH OUR SITE-- For a free on-line subscription to "This Week at Hilton Pond," send us an |

|

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond" with students, teachers, and the general public. Please see Support or scroll below if you'd like to make an end-of-year tax-deductible gift of your own.

|

If you enjoy "This Week at Hilton Pond," please help support Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. It's painless, and YOU can make a difference! (Just CLICK on a logo below or send a check if you like; see Support for address.) |

|

Make credit card donations on-line via Network for Good: |

|

Use your PayPal account to make direct donations: |

|

If you like shopping on-line please become a member of iGive, through which 1,800+ on-line stores from Amazon to Lands' End and even iTunes donate a percentage of your purchase price to support Hilton Pond Center.  Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase through them earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause! Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase through them earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause! Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. |

|

BIRDS BANDED THIS WEEK at HILTON POND CENTER 1-15 January 2013 |

|

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS WEEK: * = New species for 2013 WEEKLY BANDING TOTAL: 8 species 39 individuals 2013 BANDING TOTAL: 32-YEAR BANDING GRAND TOTAL: (since 28 June 1982, during which time 171 species have been observed on or over the property) 126 species (32-yr avg = 65.2) 58,210 individuals (32-yr avg = 1,819) NOTABLE RECAPTURES THIS WEEK:

|

OTHER NATURE NOTES: --A couple of weeks ago the Center's photo essay dealt with effects of our on-going Piedmont drought. We included an image of an Eastern Elliptio clam with unusual holes in its shell. After that posting we heard from several experts who have a likely explanation for those holes. To read what the malacologists said, scroll down to the newly added "Postscript" at the end of installment #557 at The Shrinking Pond. --A temperature of 74 degrees on 13 Jan--as indicated by the Center's digital weather station--was probably very close to a all-time record high for the date. (The average daytime high for the month is 53, with a January record of 80.) --The Center's Yearly Yard List 2013 of birds seen on or over the property stands at 24 species as of 15 Jan. --Last week's photo essay was an easily digestible summary with eye-pleasing photos of the 2012 Bird Banding Season at Hilton Pond. It's archived and always available as Installment #560. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center |

Our advisor was the late Dr. Harrison "Bud" Tordoff--esteemed ornithologist and past president of the American Ornithologists' Union. Bud

Our advisor was the late Dr. Harrison "Bud" Tordoff--esteemed ornithologist and past president of the American Ornithologists' Union. Bud  With the help of Jean and her husband Dave--plus hyper-energetic chickadee expert Jim Howitz and several undergrad volunteer assistants--we prowled Cedar Creek's oak savannah and the subdivision. That first year in a relatively small area of about 120 acres the team located more than 100 jay nests! Not all were active at one time; some were abandoned due to competition or predation, while others may have been "practice nests" by newly established breeding pairs. In each of the following two seasons we found even more nests that represented what was apparently the highest nesting density ever described for the species.

With the help of Jean and her husband Dave--plus hyper-energetic chickadee expert Jim Howitz and several undergrad volunteer assistants--we prowled Cedar Creek's oak savannah and the subdivision. That first year in a relatively small area of about 120 acres the team located more than 100 jay nests! Not all were active at one time; some were abandoned due to competition or predation, while others may have been "practice nests" by newly established breeding pairs. In each of the following two seasons we found even more nests that represented what was apparently the highest nesting density ever described for the species.

In this way, Blue Jays play a very important role in disseminating the genes of oaks, and of expanding the hardwood forests of which these trees are an integral part. Here in the south I've even seen a Blue Jay stuff an entire unshelled Pecan in its mouth and take off for who knows where, thus insuring the Pecan's offspring has a chance to sprout and flourish far from the mother tree.

In this way, Blue Jays play a very important role in disseminating the genes of oaks, and of expanding the hardwood forests of which these trees are an integral part. Here in the south I've even seen a Blue Jay stuff an entire unshelled Pecan in its mouth and take off for who knows where, thus insuring the Pecan's offspring has a chance to sprout and flourish far from the mother tree.

Oct 15 to Mar 15:

Oct 15 to Mar 15: