|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

AUTHOR'S PREFACE: September 15, 2013 marked my 67th birthday. Facebook once provided "Birthday Causes" through which a celebrant named a favorite charity to which friends could donate. This was a great way to raise funds for Hilton Pond Center & Operation RubyThroat, but FB has canceled the program. We still need operating funds, however, especially in a year that brought unexpected big expenses. I'd still like to designate Hilton Pond Center as my "Birthday Cause" for 2013. If you find my postings--especially "This Week at Hilton Pond"--to be informative or just fun to read, or if you've learned something about hummers through Operation RubyThroat, please consider granting my "Birthday Cause" wish by making a tax-deductible donation via PayPal or Network for Good (links are below), or by check (1432 DeVinney Road, York SC 29745). The goal was to have $3,500 by 30 September and generous contributors donated $1,987 by month's end; we fell a bit short but I hope you still can help with a gift in any amount. (We'll count anything received within 30 days of 15 September toward the birthday fund drive.) Thanks for your support, and thanks for letting me share my love of nature with you! BILL HILTON JR. All contributions are tax-deductible on your SEPTEMBER SURPRISES: September can be a surprising month when nature is finishing up its summer frolic and starting to look toward a less active winter season. No matter how many times we walk the trails around Hilton Pond we always encounter surprises, and this last week of September there are three we'd like to mention: An industrious spider and her oversized web, a Mourning Dove with unusual plumage, and a bug new to the Center--and to North America.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We sometimes tell visitors to Hilton Pond Center when we deploy mist nets to capture birds we're merely imitating spiders that for millions of years have been using similar techniques to capture insects. (In some cases spiders, too, catch birds in their webs.) We usually also say the main difference between spider webs and mist nets is the larger size of the latter, but this week we saw something that may cause us to reevaluate that statement. One bright afternoon we looked across the pond from the old farmhouse and noticed a spider's web back-lit by the sun. It seemed rather large, but it wasn't until we neared the pond we realized what a major undertaking it must have been to build this gossamer structure (above). From the anchor points in a Red Maple on the right side of the photo and the Hazel Alder on the left this web was a whopping 15 feet long--a "September Surprise" that was undoubtedly the biggest spider web we've ever encountered.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center From a closer vantage point we could see there were actually several anchor lines--two long ones top and bottom that formed an extended horizontal "Y," plus several lesser reinforcing lines. Within the "Y" the spider had strung upwards of 20 spokes that supported what appeared to be increasingly large concentric circles. (These "circles" actually start out as a single spiral, but it looked like this web had been damaged and repaired several times, altering its original symmetry.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Getting even closer we finally saw the architect of this jumbo-sized web: A member of the Orbweaver Family (Araneidae)--sort of a misnomer since the round web web is flattened rather than spherical. It was a large female--a male spins a much smaller web or just hangs out warily on the perimeter of the one constructed by his prospective mate--and in the afternoon light we recognized her as a Redfemured Spotted Orbweaver, Neoscona domiciliorum.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center This species is quite "hairy," covered by bristly extensions of the exoskeleton that may give the spider more sensitivity to touch stimuli and/or make it less likely to being eaten by predators. We see this species annually at Hilton Pond Center; the photo just above was taken in 2006 on the porch of our old farmhouse in a web that was far smaller than the 15-footer we found this year near the pond. Our second "September Surprise" came one day this week when we were leading a Guided Field Trip at Hilton Pond Center for a group of enthusiastic adults from Columbia SC. As we talked about bird banding, a largish bird hit one of our mist nets; it turned out to be a recently fledged Mourning Dove with atypical plumage. The bird had all the standard colors but its tail feathers revealed an interesting story we told the group, as follows . . . .

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Baby birds hatch out in one of two ways: Either downy (like ducks and fowl) or naked (like most songbirds). Doves aren't songbirds, but their chicks are born very prematurely--i.e., blind, naked, and unable to thermoregulate. Fairly soon the nestlings develop down feathers (which helps maintain body temperature) and their eyes open (all the better to see parents approaching with crops full of food). It takes several days for a squab's follicles to start making sheathed feathers that eventually cover most of the bird. Wing and tail feathers are last to develop--which is why baby birds are unable to fly. A young bird's tail feathers (rectrices) grow simultaneously, but in Mourning Doves they end up having staggered lengths--the central pair long and each succeeding pair being somewhat shorter (see photo above).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The dove we caught this week had fully grown rectrices, but its tail feather tips were quite peculiar, with a white line in exactly the same place near the tip of each rectrix. These lines are called "fault bars" or "stress bars," places in the feathers indicating the bird had some sort of problem on the day that feather was growing. Perhaps conditions were cold and rainy, or maybe the parents had trouble providing food; either situation is capable of causing a change in normal feather growth. Most interesting is that the fault bars were indeed near the tips. Because feathers grow from the base, that means stress probably occurred on the first or second day of tail feather development when the chick was still quite young. This is actually better than having fault bars when, for example, feathers are halfway grown; a fault bar is often a weak place that allows a feather to break, and a dove with just the tip missing from each tail feather would be in much better shape than one with all its rectrices broken off mid-shaft.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Incidentally, close examination of the top photo above reveals most of the dove's feathers had more than one fault bar--indicated by dark or light transverse lines--and there's even one noticeable fault bar in the buffy undertail covert. This young Mourning Dove--likely a local resident--must have had a rough go as a nestling, but it flew perfectly well after being banded and released by the group. A migratory bird with heavy fault bars might not fare so well--which is why we were surprised this past March in Belize to capture an immature long-distance migrant Gray Catbird (above) with noticeable faulting in the feathers of all its primary and secondary wing feathers. (NOTE: Adult birds also can show fault bars. Sometimes these occur in single feathers, but during normal molt tail feathers are lost and replaced sequentially in pairs, so fault bars would occur in the same place on corresponding feathers on either side of the tail.) Our final "September Surprise" truly was surprising--a new species we'd never seen at Hilton Pond Center, or elsewhere. As we slid open the patio door of the old farmhouse one morning this week, a brown object dropped to the wooden planks of the back deck. An insect of some kind, we noted, apparently one of the stink bugs.

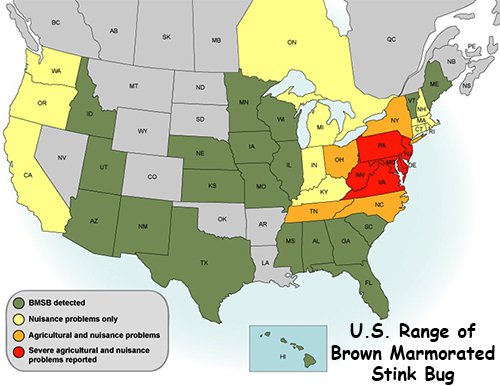

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Just the day before we'd read an article in our local Rock Hill SC newspaper about a recent U.S. invasion of the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug--an East Asian import first detected in Pennsylvania back in 1996. This 5/8"-long creature is a member of the True Bug Order (Hemiptera) that apparently has found North America to its liking. In less than two decades Brown Marmorated Stink Bugs (BMSB for short) swept across the continent--much to the chagrin of farmers from New England to Florida and from California to Washington State (see map above). This bug is voracious and opportunistic, using its hypodermic-like mouth parts to suck juice from commercial crops such as apples, cherries, raspberries, green beans, and soybeans, among others--plus ornamental trees and shrubs. BMSB do seem to be non-selective, so we wouldn't be surprised to hear the little suckers have been going after South Carolina's peach crop.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Stink bug feeding activity damages fruit or seed and makes it unmarketable (see photo of apple, above), causing a big economic hit on affected farmers. With all this in mind, we carefully examined the insect we'd just collected on the back deck and, sure enough, its field marks indicated it was indeed the culprit about which we'd just been reading. (A couple of days later we found a second Brown Marmorated Stink Bug clinging to a sliding screen door leading to the back deck, so lots more are likely lurking in Hilton Pond shrubbery.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Why such a little insect has a common name (Brown Marmorated Stink Bug) even longer than its scientific epithet (Halyomorpha halys) is anybody's guess, and since there's apparently only one kind of stink bug that's "marmorated" they even could have left off "brown." (We now know "marmorated" means "marbled"--a reference to the pattern on the BMSB's dorsal surface. They could have just called it "Marbled Stink Bug" and saved some letters--but then not as many folks would go to the dictionary to look up "marmorated.") Native stink bug species abound in the U.S.; some are distinctly bright green while others are brown and superficially similar in appearance to the BMSB. So what to look for in positively identifying this recent invader from the Far East? The principal field marks for Brown Marmorated Stink Bugs are these: 1) White bands on the antennae; and, 2) Alternating black and white markings on the outer edge of the abdomen where it sticks out from beneath the wings. (These characteristics are visible in one or the other of our two photos--taken on macro setting while the two captives wandered aimlessly around an optically impure glass jar on our computer desk. A ventral view through the glass, below, also shows the bug's prominent juice-sucking stylet.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center If you've ever encountered a stink bug you will understand whence cometh its name. Through abdominal holes the insects release a pungent odor that undoubtedly makes a predator drop its intended lunch in a hurry. Some stink bugs yield a strong but not overwhelming medicinal fragrance, but the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug emits a powerful stench--sort of a cross among cilantro, citrus, and dirty socks. (As always, we wish we could add a Scratch n' Sniff component to our Web pages.) The big problem with BMSB odor--to which some folks are allergic--is it's long-lasting; this is especially distressing when we discover BMSB have the disarming habit of clustering in human dwellings during fall and winter months, sometimes stinking up the house for the duration of the cold weather season . . . and thereafter. Once the odor is established, it attracts even more BMSB in ensuing years. If you get a Brown Marmorated Stink Bug in your living room, do what you can NOT to irritate it. Let it crawl into a plastic cup or onto a piece of paper and escort it outside. Don't squash it (that REALLY releases the stench), don't suck it up with the vacuum cleaner (the odor will hit you again every time you vacuum), and don't waste precious water by burying it at sea in the toilet (besides, the bug may give off a parting shot as it goes down the drain). Better to let it go unmolested, even though it may live to breed the next spring. And be glad you don't live in Maryland and Pennsylvania, where a couple of times each week some homeowners fill two-gallon buckets with congregating BMSB.

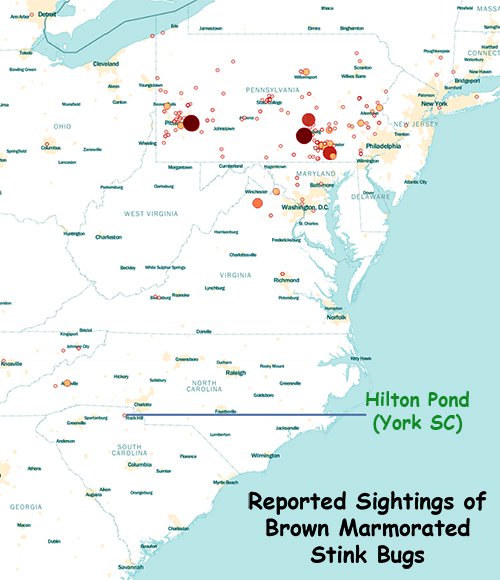

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center With few natural enemies, BMSB are destined to expand their reach in North America, and it appears there's not much we can do about it. (Insecticides that are effective on stink bugs often kill beneficial insects, too.) That said, you may wish to join a citizen science project that at least documents the widening occurrence of Brown Marmorated Stink Bugs. The Web site stinkbug-info.org allows you to register, report, and map BMSB. On the map above, our Hilton Pond sightings of this invasive species are the only ones reported from South Carolina through 30 September. How ironic we found our first Brown Marmorated Stink Bugs the day after learning about them from an article in the local newspaper. An orbweaving spider and her humongous web, a Mourning Dove fledgling with unusual tail (and interesting tale), and a stinky new bug at Hilton Pond Center--such are our "September Surprises" the last ten days of the month in 2013. We can hardly wait to see what astonishments October will bring. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center All contributions are tax-deductible on your |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

Comments or questions about this week's installment? Send an E-mail to INFO. (Be sure to scroll down for a tally of birds banded/recaptured during the period, plus other nature notes.) |

Please report your sightings of

Please report your sightings of