|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

HUMMINGBIRDS IN HONDURAS:

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center PREFACE In February-March 2014--thanks to the gracious hospitality of James Adams--principal investigator Dr. Bill Hilton Jr. and long-time guide and colleague Ernesto M. Carman stayed at the Lodge at Pico Bonito during a Ruby-throated Hummingbird scouting trip near Honduras' Caribbean coast (see map above).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center DAY FIVE--1 March 2013 Our first four days at Pico Bonito were filled with birds and flora of the montane forest, but on Day Five we tried something very different: A boat trip to islands about 45 minutes off the Honduras coastline. After breakfast The Omega Group and Esdras headed down the mountain to La Ceiba and then on to Sambo Creek. There, boats depart daily for fishing and diving excursions at Cayos Cochinos (AKA the "Hog Islands")--renowned as one of the finest areas for snorkeling in the entire Caribbean region.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Cayos Cochinos group consists of two larger islands, Cochino Grande and Cochino Pequeno (Big Pig and Little Pig) and numerous smaller cays--all surrounded by live coral reefs. Our goal that day was twofold: 1) Get a good look at the famed (among herpetologists) Hog Island pink Boa Constrictors; and 2) Introduce both members of the Omega Group to snorkeling--an activity neither of us, somehow, had ever experienced.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The 45-minute boat ride came via a speedy little covered craft complete with first mate (above), captain/pilot/guide, and two outboard motors. The trip was rather pleasant--in part because waves were cresting at only about one foot. (A snorkeling group from the lodge met so much choppiness a few days previous they had to stop for more than an hour to wait for seas die down.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center En route we passed a small island (above) with a few nicely built structures that allowed local fishermen to rest overnight or take refuge from storms without returning to the mainland. We actually put in there momentarily to drop off a cooler and some supplies for guys on the island.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Continuing on we finally got to Little Pig Island, where along with several other boatloads of tourists we watched a video about the Cayos Cochinos marine refuge and were reminded about the fragility of coral reefs. With hundreds of people visiting daily, it was worth remembering we ought to look at nature and not touch. That old slogan in U.S. national parks of "Take only photos, leave only footprints" has to be modified here to include just photo-taking; walking on coral while snorkeling would soon destroy the work of all the tiny creatures that slowly build those reefs.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The video finished, our boat-captain-now-land-guide led us on a trail to Little Hog Island's interior, where the first creature we encountered was an unidentified terrestrial Hermit Crab hanging from a branch. Its shell--which appeared to be well worn and perhaps a hand-me-down from a predecessor--fit the crab perfectly and allowed retreat inside should a potential predator take interest. The crab obviously saw us and our cameras as no threat so it continued navigating limbs of a short shrub. (As always, if you know scientific and/or common names for this crab or any other unidentified organisms in our write-up, please e-mail it to INFO.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A little further on our guide came to a sun-dappled clearing (above) and stopped in his tracks, telling us (in Spanish) to "Find the pink boa." Despite our supposed skills as field naturalists, we scratched our heads, looked high and low, and after several minutes finally figured out the six-foot snake was right in front of us--lined up exactly with a diagonal branch. Talk about cryptic coloration and behavioral camouflage!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center This particular individual was well-known to the guide and probably an older female since adult males are usually a bit smaller. A close view of her head (above) showed some of the rosy coloration and pale markings that--along with very docile natures--made this race of the Boa Constrictor a darling of the pet industry. Such yearning for Hog Island Pink Boas decimated local populations and eventually led to strong protective measures by the Honduran government and several conservation organizations. The boas have been monitored closely for the past decade or so, and most have pit tags embedded beneath their scales; this allows them to be identified at recapture and tracked individually. Any ad for a "wild caught Pink Boa" indicates some disreputable collector has stolen a serpent from one of the Hog Islands and should be reported.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We did get better at spotting Pink Boas along the Little Hog Island trail. Can you see the one in the image above? (HINT: It's resting in plain view on the horizontal branch near the center of the photo!)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center This particular boa was much smaller--perhaps two feet long, and far more slender. but a close view (above) showed the hypomelanistic rosy hue that makes this population different from other races of Common Northern Boa Constrictors. Despite their geographical range, all are Boa constrictor imperator--the subspecies found across Central America into northern South America. (The much bigger and more commonly kept Red-tailed Boa, Boa constrictor constrictor, is native to South America.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center While we watched various snakes sunning in the Little Hog Island forest, a local boy came down the trail with two recently born baby boas in his hands. He was eager to share them with us and wanted to take them out to show tourists at the nature center. We didn't want to encourage this behavior, so Ernesto gently suggested in Spanish the boy go out to the beach and bring the tourists back to see snakes in their native habitat. Happily--and perhaps hoping for better tips--the youngster thought this was a good idea and followed our advice, so perhaps we made some small contribution to the conservation of Hog Island pink boas in the short time we were there. Who knows, maybe the kid is a future nature guide who'll do things the right way.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Bidding the pink boas adios, we re-boarded the boat and headed toward Big Hog Island for what would become an inaugural snorkeling event for both Bill and Ernesto. Along the way we had one more treat: Racing with a pod of Bottlenose Dolphins, Tursiops spp., that outran the speedboat with apparent minimal effort. We easily could see these streamlined mammals in the clear blue water and we identified several individuals by distinctive spots or, in one case, by a scar on a dorsal fin (above). We've always thought these marine mammals--along with whales--are a lot more intelligent that we give them credit for. We don't mean to appear too philosophical rather than scientifically objective, but maybe if we humans put harpoons aside these cetaceans could teach US a thing or two about protecting the marine environment.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We found snorkeling to be fun, especially for Ernesto; his keen eyes were able to spot all sorts of underwater life,and he was enthralled by just being in deep saltwater for the first time in his life. For near-sighted Hilton, however, a lot of the coral reef was simply a colorful blur; prescription goggles might improve the experience if we ever give it another shot. In any case, we hadn't brought watertight containers for our cameras and took no photos, but the public domain Internet image above shows the very same Big Hog Island reef over which we swam. We're pleased to report it's a spectacular place with incredible diversity that somehow remains unpolluted by effluents dumped into the seas by generations of thoughtless humans.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Snorkeling was energetic enough to be appetite-inducing, so after a few hours of frolic we eventually re-boarded the boat and headed back to an island closer to the mainland. There we watched numerous Brown Pelicans (white-headed adult, above), paddling about and begging from tourists and local fishermen.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center These Brown Pelicans (brown-headed immature, above), were so tame several tourists got in the ocean and waded among them, but we members of the Omega Group had our fill of the water and wanted lunch instead.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our boat cabin took us to one of several small, ramshackle cottages lined up along the shoreline and instructed us to sit in the shade at a picnic table. First, however, we couldn't resist the urge to stroll out back where local women (above) were frying fish and baking bread in an outdoor oven.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The meal the women served was incredibly good, and not just because we were famished from snorkeling. Freshly caught Yellow-tailed Snapper (above), beans and rice cooked in coconut oil (NOT palm oil), and some of the best fried plantain we've ever eaten. Very filling, and very, very yummy!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center With that meal in our bellies our day of introduction to the Caribbean Sea was complete, so we took a last look toward the mainland (above), climbed aboard our speedy craft, and got back to the Lodge at Pico Bonito just in time for . . . supper!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center DAY SIX--2 March 2013 On our sixth day at Pico Bonito we devoted an entire day to investigate an unusual Honduran habitat--a tropical thorn forest--and to look for one of the world's rarest hummingbirds, the endemic Honduran Emerald. As the hummer flies the thorn forests were barely 20 miles away (see map above), but they were on the OTHER side of an insurmountable Pico Bonito range--meaning we had to drive east and then west to get to Valle de Aguán. The destination was four hours away on the south side of the mountains.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center With ever-dependable Lima as our driver, the Omega Group and Esdras and a tag-along birder named Pamela boarded the van at 4 a.m. and headed out pre-dawn, stopping along the way for sunrise views of a riot of roadside wildflowers (above). These included Lantana and Blue Porterweed--two nectar-bearing plants we've seen Ruby-throated Hummingbirds visit throughout Central America.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We knew we were approaching our destination when at a crossroads in the town of Saba we found a little park with a sculpture of an oversized five-foot-long hummingbird (above). Although not anatomically correct, the metal artwork showed local residents were aware of the importance of the Honduran Emerald--if not for its environmental significance then at least for local tourist dollars.

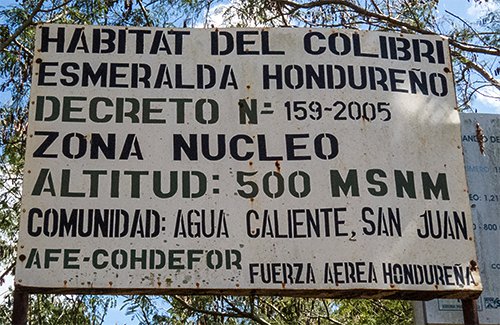

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After more driving--and a few catnaps--we finally reached an rambling hacienda in the community of Agua Caliente and parked in the shade of one of the few tall leafy trees we could find. The humidity was quite low in this valley--after all, it lay in the rain shadow of the Pico Bonito range--but even by 8 a.m. temperatures had risen higher than we had seen them all week back at our cool mountain retreat. A sign (above) proclaimed this site (at 1,500 feet elevation) as the dry thorn forest habitat of Esmeralda Hondureño--the Honduran Emerald we sought.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Tropical thorn forests occur in isolated, fragmented, ever-smaller patches in the driest parts of inter-mountain valleys on the Caribbean Slope of Honduras and Guatemala. More extensive during a colder and drier Pleistocene Era, most of these habitats are greatly reduced due to expansion of pine forests and--in modern times--the rapid advance of agriculture and cattle ranching. Thorn forests of greatest concern are in northeastern Honduras south of the Pico Bonito mountain range. This valley (Valle de Aguán) is home to the Honduran Emerald, Amazilia luciae--the whole country’s only endemic bird--plus endemic races of numerous other vertebrates, invertebrates, and flora. It wasn't surprising to learn that with loss of the thorn forests, the Honduran Emerald is a critically endangered species, with somewhere between just 250 and 1,000 adults left in the world. Fortunately some of those birds are in two new sites recently discovered in western Honduras, which helps minimize the possibility an entire local population might be wiped out by calamity--natural or otherwise.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As might be expected, plants in the thorn forest are highly adapted to xeric, drought-like conditions in which rains come heavily but very infrequently. Broad-leafed flora have thick, waxy leaves that retard water loss, and some are deciduous during the dry season--another adaptation that prevents desiccation via transpiration. We weren't surprised to see towering cacti in the forest, including many specimens of Old Man Cactus, Pilosocereus leucuocephalus (above)--so named for tufts of beard-like hairs that protect new growth from the ravages of direct sun.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Prickly Pear Cacti, Opuntia (Nopalea) hondurensis (above), also abounded in the shrub layer of the thorn forest, their flat chlorophyll-laden pads adapted to carry out photosynthesis in the absence of leaves. Sprouting among their thorns were omnipresent brown interpretive signs lauding the presence of a special hummingbird--even more appropriate because the Honduran Emerald is known to take nectar from the cactus' big red flowers.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Perhaps the favorite food plant of the Honduran Emerald at this locale is a native euphorb called Pedilanthus camporum (above). This essentially leafless succulent grows in big clumps of five-foot-tall pencil-think stems and sports a red blossom (below) with enough sweet nectar to attract a hummingbird's attention.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center This euphorb's common name--Slipper Plant--pertains to the shape of the blossom. In the image above, the long red pistil--which has received pollen from some bird or insect--has already folded back and a fertilized ovary will produce fruit; dark-tipped stamens and other flower parts will soon wither in the harsh desert-like sun. A Honduran Emerald visits any given Slipper Plant blossom repeatedly during the day and adds fats and proteins to its diet by hawking insects that sally forth.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We finally got a good "lifer-quality" look at a Honduran Emerald as we were preparing to depart for lunch and our drive back to the Lodge. The hyperactive hummingbird was dive-bombing a diurnal Ferruguinous Pygmy-Owl (above) that seemed little concerned by the hummer.

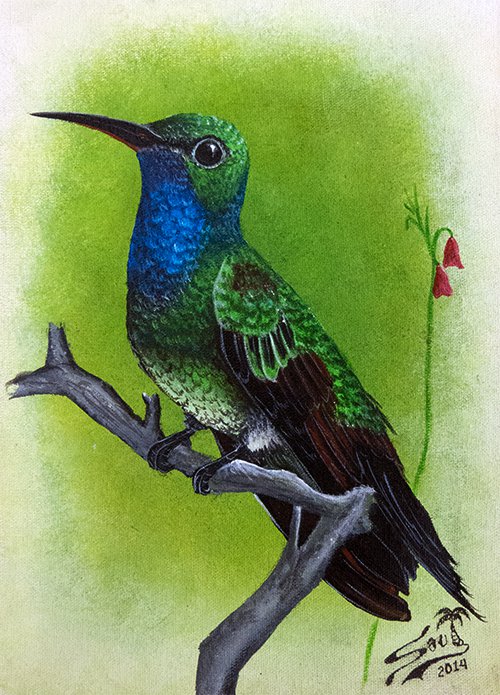

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Unfortunately, we were unable to get a decent photo of this particular Honduran Emerald but offer the image (above) by Dominic Sherony (courtesy Wikipedia). The more-or-less sexually monomorphic species is characterized by a metallic blue-green throat and upper chest, sometimes appearing gray and dusky. Its belly is pale gray with mottled green sides, with a bright green dorsum and bronzish tinge on the uppertail coverts. The tail is bronzish-green and the black upper mandible is complemented by red on the lower. (Females may be slightly duller in appearance.) During our visit to the reserve the group saw several more of these extremely rare Honduran Emeralds, and Ernesto even spotted the SECOND Ruby-throated Hummingbird of our trip to Honduras!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center DAY SEVEN--3 March 2013 The long drive to and from the Honduran Emerald reserve pretty much wore us out, so we slept in a bit on 3 March. (That means we got up at 6 instead of 5:30 a.m.!) After breakfast it was back into Lima's van for half-hour drive past La Ceiba to the little village of La Union--gateway to Cuero Y Salado wildlife reserve (see sign above).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Access to the reserve is via the narrow gauge Tela Railroad, now a federally maintained tourist attraction but once a principal means of transporting coconuts cultivated by United Fruit Company.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Cars on the three-foot-wide track now pass through the small town of Monte Pobre and transport students and other residents back and forth.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A few coconut plantations (above) remain near the end of the line, constructed because it was much more difficult--even more dangerous--to transport coconuts via boat along the sometimes stormy coastline of northern Honduras.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Local entrepreneurs still harvest coconuts (above) and occasionally take them to market via the train. (One hard and fast rule of coconut farming--or photographing: Never stand under a coconut tree for too long--at least not without a hard hat and shoulder pads!)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center At the end of the rail line is a small visitor's center with restrooms, a dock, and a skeleton of a West Indian Manatee, Trichechus manatus (above), a species that often swims inland to dine on Water Hyacinth and other aquatic plants. These animals are highly adapted to grazing, with prehensile upper lip, no incisors or canines, and big grinding molars. They have extremely long intestines--130 feet or more!--which provides room and time for microbes to digest the cellulose in the manatee's diet. We saw no manatees during our visit but were assured by locals the rare aquatic "sea cows" make regular visits.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When we disembarked the train we were met by a man carrying a trolling motor, a paddle, and three floating cushions. He motioned us to his boat (above, with the Pico Bonito range on the horizon) and headed back upriver along a waterway that flows to the Caribbean Sea.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our first notable sign of nature was a cluster of Brazilian Long-nosed Bats, Rhynchonycteris naso (above), hanging head-down on a sign telling us we were at the edge of the Cuero Y Salado wildlife reserve. In the Neotropics we've most often seen this species--also known as the Proboscis Bat or River Bat--grouped on tree trunks hear a stream or pond. Only about 2.5" long, this bat occurs all the way from southern Mexico to south-central Brazil.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The first bird of the morning was the smallest member of the New World Cerylidae--an American Pygmy Kingfisher, Chloroceryle aenea (above). This tiny bird is only five inches long from bill tip to end of tail, barely one-third the length of the more-familiar Belted Kingfisher; it dives for minnows or tadpoles and even hawks for large insects. As is typical of kingfishers, the female is more colorful and has a blue necklace; thus, the bird in our photo is a male.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As we motored upriver we noticed spectacular eight-inch blossoms of a Provision Tree, Pachira aquatica, so-called because the pollinated flower produces a huge fruit with multiple nuts that supposedly could be used for food in times of hardship. Similar to peanuts in flavor, they can be cooked, eaten raw, and made into flour. Some locals even eat the leaves and flowers. Also called "Money Tree," the plant has been exported to Asia where gardeners braid the trunks of several trees as a good luck charm. We have seen Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in Costa Rica (Guanacaste Province) nectaring on this tree's close relative Pochote, Pachira quinata, so we're guessing the Provision Tree also gets visited by hummers.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Not far from the Provision tree was one of several wading birds we observed along the river, the one above being an adult Little Blue Heron, Egretta caerulea. Dark-tipped blue bill, green legs, and purplish head are excellent field marks for this species, although the immature's plumage is all white and superficially resembles several other heron/egret species.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A little further on we spotted a long-tailed, long-toed Common Basilisk, Basiliscus basiliscus (above), sunning on a snag overhanging the river. This big lizard was nearly three feet long, two-thirds of which was tail. Basilisks also go by a somewhat irreverent nickname lagarto de Jesus Cristo ("Jesus Christ Lizard") for their ability to actually run across water. Basilisks are omnivores, using their many saw-like teeth to dine on everything from flowers to fish and small reptiles to insects. Pursued by predators, basilisks do indeed skitter across the water for ten yards or more but also can dive and stay submerged for up to half an hour.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After riding the main river for 30 minutes or so our captain turned into a side channel, where he cut the motor and let us drift into a dark and eerie forest of mangrove trees. "Mangroves" include more than 110 tropical tree and shrub species worldwide--all with a peculiar growth habit: Sending down long extensions of trunks and limbs to make an inter-tangled network of roots that support the trees in wet conditions. The roots also help retain soil and provide myriad places for diverse creatures to hide and thrive.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Should one wonder whether the mangrove forest rises up in fresh or brackish water, one only need look at white structures (above) on some of the roots. These obviously were marine barnacles--crustaceans that occur only in waters with some degree of salinity. In these mangrove channels, fresh water rushes from the mountains to the sea, but at high tide a backflow brings saltwater back inland and raises the salinity. Mangroves are among the few plants well-adapted to this constant change from freshwater to salty. We contemplated all this while floating slowly through the side channel. It was an almost-primeval experience, the quiet of the mangroves punctuated only by bird calls and, once, by the plaintive but useless screams of a large frog being devoured alive by a White-faced Capuchin Monkey.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Amid the mangroves roots at the edge of the channel our sharp-eyed guide noticed a subtle movement and pointed his boat in that direction. There, in subdued light, we still could see bright colors and markings of a bird (above) avidly sought by birders coming to this part of the world: Agami Heron, Agami agami. Rarely seen, this species has rather short legs for a wader, an adaptation that allows it to navigate the tangle of mangrove roots as it searches for prey.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Agami Heron has greenish wings and back marked with chestnut, with a pale blue crown. Its most distinctive marks, however, are unusual thin blue feathers on its neck and breast. The species is sometimes called Chestnut-bellied Heron for the color of its undersides, but "agami"--an indigenous word for the bird--sounds much more exotic.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Agami Heron is a stalker that moves very slowly in shallow water in pursuit of small fish, amphibians, and reptiles, and an occasional snail. Our informative photo above shows the heron snatching a fish with just the tips of its pincer-like bill--which is relatively long for the size of the bird.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although we enjoyed watching the Agami Heron feed in this idyllic mangrove setting, the guide had more to show us and took his boat back into the main channel. There, on a large fallen log we saw yet another lizard basking in the tropical sun. This time it was a youngish male Green Iguana, Iguana iguana (above), already nearly three feet long. At maturity this individual will develop a bigger head, stouter body, longer spines, and a more pronounced dewlap--the fold of skin under the neck--all of which apparently signals a female he is worthy of fathering her offspring.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Near the iguana was a lavender-colored flower (above) of interest to anyone who like hummingbirds. Growing from a vine with compound leaves, we did not know its specific name but recognized it as a member of the Bignoniaceae. This plant family contains Trumpet Creeper, Campsis radicans--that tubular, nectar-laden, orange-red blossom that grows profusely back at Hilton Pond Center and the eastern U.S. and is a summertime magnet for our Ruby-throated Hummingbirds.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As a way to educate visitors to the importance of Honduras' coastal wetlands and mangrove stands, the government installed a short overland boardwalk across the river from the nature center. Our guide let us off there so we could walk through the forest without getting wet. As further indication of local salinity, we observed a colony of Fiddler Crabs burrowing in the soft mud. These invertebrates take their name from the oversized right or left claw of the males (above), which wave their pincers in the air apparently to mark territories and attract females. Having experienced the boardwalk we clambered aboard the boat to cross the river, where the old coconut train was waiting to take us back to the van that would--in turn--transport us back to Pico Bonito for the rest of the day. Car, train, boat, and on foot--all ways to get around Honduras to see the natural sights. DAY EIGHT--4 March 2013 During the daylight hours on 4 March, trip leader Hilton opted to stay back at the Lodge working on what became last week's installment about our first four days in Honduras--lest he fall so far behind on sorting photos and writing text that "This Week at Hilton Pond" would be 'way out-of-date. Intrepid Ernesto and Esdras decided on a challenging all-morning hike up some of Pico Bonito's steeper and more arduous trails, all in the hope of adding a few bird species to the ever-growing trip list. Among other things they sighted our third--and final--Ruby-throated Hummingbird for the ten-day trip to Honduras.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One can sit at a laptop computer for only so long when surrounded by sights and sounds of a tropical forest, so trip leader Hilton did get up and walk around a bit with camera at hand while 'Nesto and Esdras were out birding. One treat was watching and photographing a male Black-cheeked Woodpecker, Melanerpes pucherani (above), eating fruit from a bamboo feeder maintained by staff at the Lodge. (Females have a black crown.) This species resembles the "ladder-backed" Red-bellied Woodpecker we see on a daily basis back home at Hilton Pond Center and is, in fact, in the same genus.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center That evening under clear skies and a crescent moon (above), the Omega Group went out after dark with headlamps and camera flash to learn what sort of night creatures could be seen and maybe even photographed. Among other enhancements, Lodge personnel have constructed a concrete pool up the trail near the lookout tower--all in an effort to attract rare frogs and other amphibians. We made this frog pond our first stop and were not disappointed.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center It took us only a moment to find the acrobatic stars of the pond, none other than Red-eyed Tree Frogs, Agalychnis callidryas (above). Although this species occurs from southern Mexico through Central America to northern Colombia, trip leader Hilton had never encountered it in the wild as was understandably fascinated. It was important not to bump palm fronds among which the frogs were hiding; males of this species actually shake vegetation upon which they sit to deter prospective rivals from coming near.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Red-eyed Tree Frogs are appropriately named for their bulbous crimson eyeballs with vertical slit pupils. Their backs are pale green with a few distinctive white spots, while their undersides and toes are orange with bluish markings on the flanks.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center These particular frogs are true Tree Frogs, with large circular pads at the end of each toe. Pads are not sticky, per se, but have tiny grooves that adhere to and easily free from a substrate.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Red-eyed Tree Frogs are a threatened species throughout their current range, primarily because of commercial, residential, and agricultural development. Logging especially has decimated their sylvan habitats. The population at Pico Bonito seems to be doing well, if the copulating pair above is any indication. The male holds on tight for hours or days at a time in a posture known as "amplexus," thereby preventing other males from mounting when the female finally begins to lay her egg cluster in the pool below. Sperm are simply broadcast over the eggs and it's always been a wonder to us they get fertilized at all.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another amphibian attracted to the Lodge's pond was the Honduran Golden Toad, Cranopsis (Bufo) leucomyos (above). A resident of moist lowland forests, this animal is endemic to Honduras and is endangered--again by loss of habitat. We hadn't expected these flaxen-colored toads and were pleased to see several individuals in this artificial habitat.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Not wanting to disturb the frogs and toads much further with our lights, we made our way back to the tower where by day earlier in the week we had observed Lovely Cotingas across the gorge. We climbed the tower in darkness, hoping to rustle up a few owls or potoos. Ernesto brought his audiolure for just such purpose and played the growling call of the Northern Potoo. In matter of minutes we saw--and felt--a shadowy shape flutter by in the dim light of the crescent moon. The "ghost" settled in about 40 yards away on the top of a bamboo snag--just the right place for a potoo to hang out. When we shined our headlamps into darkness, what came back was the red eyeshine pictured above--a spooky sight to say the least.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Focusing a camera on a ghostlike bird in full darkness is no easy task, but we finally got our camera flash to illuminate the distant bird well enough (above) for identification. It was indeed a Northern Potoo, Nyctibius jamaicensis, a nocturnal bird with a small bill but an enormous gape. Potoos superficially resemble owls but aren't even distantly related. They sit on their perches by night and fly out to capture large beetles and insects they swallow whole. And they have red eyeshine. DAY NINE--5 March 2013

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center On Day Nine we resigned ourselves to computer work and general birding around the Lodge, knowing this would be our final full day at Pico Bonito. We couldn't resist making a purchase at the on-site gift shop: One of those amazing pottery pieces (12" vase, above) created from multiple kinds of clay by Lenca Indians.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In the afternoon we went back down to El Pino to visit one last time with Esdras Lopez and to pick up some more artwork by Saul Cordoza and Yanela Romero. We had purchased Saul's painting of Lovely Cotingas several days earlier and commissioned him to paint a Honduran Emerald as a memento of our trip to his country. Saul obliged and produced the nicely rendered canvas above.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We also had asked Yanela to apply her skills to making and signing a few custom-made keychains (above) to take back as souvenirs, two depicting Lovely Cotingas and one with a head of a female Lineated Woodpecker. This artwork was shamefully inexpensive--Saul's two paintings were only $10 each and the keychains $2.50 apiece--but our payment and tip still provided neighborhood artisans with important income.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We got an unexpected bonus while we re-visited the artisans and guides co-op on our last day. Panthera, an international conservation dedicated to protecting wild cats of the world, had sent to El Pino a team of researchers and educators (above) to spread word about Jaguars, Panthera onca, in the area around Pico Bonito. Their visit was sparked by unfortunate news that a local lawbreaker had intentionally shot an protected Jaguar and accidentally allowed its carcass to wash downstream where it was found by angry citizens who understand the importance of protecting this increasingly rare species. Jaguars--third largest cats in the world--are listed as "near threatened" across their entire range from the southeastern U.S. to almost the southern tip of South America. Regretfully, they have been extirpated from many locations with that range.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center On our final night at the Lodge at Pico Bonito we asked the staff to turn on an electric lamp hanging over a white sheet they sometimes put out to attract moths for folks to observe and photograph. Since we also had to pack our luggage we only spent a few minutes observing but still managed to get images of four moths (above and below) that were attracted to this "light trap." We haven't identified any of these night-flyers--including the gold-spattered Moth #1 above; if you know what any of them might be, please send an e-mail to INFO.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Moth #2 (above), whose markings may mimic bird droppings.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Moth #3 (above), with marks somewhat reminiscent of a big bee or hornet.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Moth #4 (above), with white wings and black edging. DAY TEN--6 March 2013

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Omega Group had to rise bright and early on Day Ten, postponing breakfast until we completed the 2.5-hour drive from Pico Bonito to the airport at San Pedro Sula. Driver Lima got us there just at dawn (above), three hours ahead of our scheduled one-hour flight to Belize City via a TropicAir ten-seater. We thanked Lima for his safe driving during the week, had a sumptuous Honduran airport breakfast of baleadas (wheat flour tortillas, folded over and filled with mashed fried beans and bacon), checked in, cleared customs and immigration, and got ready to depart for our upcoming Operation RubyThroat expedition to Crooked Tree--the subject of next week's installment of "This Week at Hilton Pond." Serendipitously, in the airport waiting area we ran into Julio Valladares, an associate of Holbrook Travel and the Road Scholars program who had just learned about some Aloe Vera plantations in western Nicaragua that might be a good place to expand our mid-winter Ruby-throated Hummingbird studies. Long-time followers of our Operation RubyThroat exploits in Central America may remember this whole Neotropical extension of our hummer research began 'way back in 2004 in Costa Rica--among Aloe Vera fields that now have been plowed under! With that new knowledge buzzing in our brains, the Omega Team boarded the plane in Honduras for a flight to meet our next citizen science group in Belize. The adventure continues!

POSTSCRIPT #1: We once again express out deepest appreciation to James Adams and the staff at the Lodge at Pico Bonito for generous hospitality during our stay in Honduras. Our guide, Esdras Lopez, was especially helpful and informative. We very much wanted to use the Lodge as a base for future Operation RubyThroat hummingbird research expeditions, but Ruby-throated Hummingbirds are far too scare in the area. Instead, we enthusiastically recommend the Lodge as an excellent place to visit for birders, naturalists, families, and photographers seeking a wide diversity of Neotropical flora and fauna. (Did we mention Ernesto tallied 247 bird species while in Honduras, including several lifers? That's a very impressive total.) That said, we WILL be planning an ORT trip to Honduras, but it likely will be in to the highlands around Copan where RTHU are more plentiful. (Stay tuned for info about this trip, tentatively scheduled for late February 2015.) POSTSCRIPT #2: When we returned to Hilton Pond Center in March 2014 after our time in Honduras and Belize, we took delivery of several large boxes. We mentioned to the delivery men we'd just returned from Central America and were stunned to learn the driver was from El Pino, the little town just downhill from Pico Bonito and where our guide Esdras lived. El Pino has a population of only 3,000, so odds were pretty small our packages would be delivered in the U.S. by a guy from the Honduran town where we visited the artisan & guide co-op a few weeks previous. Small world, indeed!

All contributions are tax-deductible on your |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Dr. Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History.

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

Comments or questions about this week's installment? Send an E-mail to INFO. (Be sure to scroll down for a tally of birds banded/recaptured during the period, plus other nature notes.) |

Birding guides on James' staff said there were at least a few RTHU in the vicinity of the Lodge and at another nearby facility at Rio Santiago, so Hilton and Carman (the "Omega Group") investigated the area in anticipation of mounting an

Birding guides on James' staff said there were at least a few RTHU in the vicinity of the Lodge and at another nearby facility at Rio Santiago, so Hilton and Carman (the "Omega Group") investigated the area in anticipation of mounting an

Oct 15 to Mar 15:

Oct 15 to Mar 15: