|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

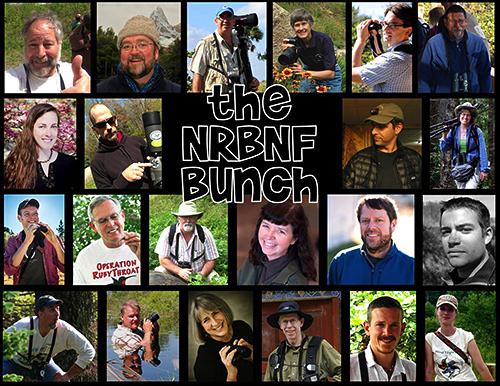

FROM WEST VIRGINIA'S MOUNTAINS TO THE CAROLINA PIEDMONT For the past 13 years, May has been a dichotomous month for us, with the first week or so spent in the highlands of southern West Virginia and the remainder back at Hilton Pond Center in South Carolina's Piedmont Physiographic Province. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The 20-plus guides and lecturers truly are at the top of their profession. Among others this year's staff included (from top left in the image above) Geoff Heeter, Mark Garland, Bill Thompson III, Connie Toops, Jim Rapp, Dave Pollard, Katie Fallon, Paul Shaw, Ben Lizdas, Julie Zickefoose, Scott Whittle, Bill Hilton Jr., Scott Shalaway, Louise Zemaitis, Michael O'Brien, Kyle Carlsen, Keith Richardson, Jim McCormac, Dawn Hewitt, Tom Stephenson, Ernesto Carman, and Rachel Davis.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In 2013 Ernesto (above, with local guide Alma Lowry and guide Connie Toops of North Carolina) came up from his family's organic, shade-grown coffee farm at Paraíso, Costa Rica, bringing an international component to the festival. Ironically, 'Nesto easily recognizes many birds observed in West Virginia because he sees them back home on their wintering grounds or migration routes. Two big differences: Up there he gets to watch those same species in full breeding plumage AND hear them sing their mating songs on territory.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Many participants in the festival spend time at the New River Birding & Nature Center at Wolf Creek Park between Fayetteville and Oak Hill. This locale--whose claim to fame is a Wetlands Boardwalk (above) that winds throughout one of the rarest habitats in West Virginia--is a favorite spot for observing species of water-loving songbirds without getting one's feet wet. It's also the site for Day Two of an annual Hawk Gawk & Warbler Walk, a fall festival that splits time between watching raptors at Hanging Rock Observatory in Monroe County WV and identifying "confusing fall warblers" as they assemble in trees along the boardwalk.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Wolf Creek wetlands were created perhaps 50 years ago by industrious American Beavers that found a relatively level expanse of land covered by hardwood forest. They chopped down oaks and maples with their super-sharp incisors, built damns like the one in foreground above, and backed up water that flooded about 15 acres. Even in the rain the wetlands--and its roofed gazebo--provide a splendid place to relax and take in the glory of nature.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As noted, we've been banding birds at the New River Birding and Nature Festival since its inception and in 13 years have caught quite a few species--including Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. Two of our most confusing (i.e., harder-to-identify) birds a few years back were seldom-seen Lincoln's Sparrows that pass through southern West Virginia on their way to breeding grounds across Canada. This year we mist netted a brightly plumaged male Yellow-breasted Chat (above), the first ever banded at Opossum Creek Retreat. This individual was highly vocal in-hand and was no exception to our belief that chats can curse more loudly and with more extensive vocabulary than any North American bird--except, perhaps, Gray Catbirds. Incidentally, chats also bite.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although bird banding is our prime responsibility during the festival, this year we helped lead several field trips and lectured twice for the group: First about our ground-breaking hummingbird research in Central America, and later on how to identify raptors in the field. In our limited spare time we had the pleasure of wandering the West Virginia woods with camera, studying and photographing the diverse flora that abound in this stretch of the Central Appalachians. Early May is too late for many of the spring ephemeral wildflowers, but there's still plenty of vegetative activity to observe--including a lush growth of mosses on the Eastern Hemlock stump (above). The presence of such greenery indicated this stretch of woodland was both shaded and moist.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Not far from the hemlock stump was a small grassy area dappled with enough sun to support a nice patch of flowering Wild Strawberries, Fragaria vesca (above). This native species occurs across temperate North America and Europe, where it propagates prolifically via above-ground runners or seeds from its scarlet-red fruit. The three-part foliage is a favorite of grazing White-tailed Deer, while the berry is sought after by all sorts of birds and mammals big and small. Humans like it, too, and there is even archaeological evidence from prehistoric stool samples that European Neanderthals knew the delight that comes from tasting Wild Strawberries. Pollination is by a wide variety of native bees, flies, and small butterflies, while larvae of Grizzled Skippers and several moths are known to dine on leaves and flower petals.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Not sure what it is about Wild Geranium, Geranium maculatum (above), that pleases us so much, but it is without doubt one of our favorite wildflowers. This herbaceous perennial is native to most of eastern North America's woodlands where it blooms in mid-spring to the benefit of larger native bees, flies, and beetles that take its pollen and nectar. Note the dark lines on each pale violet petal; these are "bee guides" that direct insects toward nectaries at the bases of the stamens. Interestingly, like some other wildflowers that make blossoms when cool spring weather diminishes insect activity, Wild Geranium is also capable of self-fertilization.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center With nearly 600 species of Buttercups (Ranunculus), it could have been hard to know which one (above) we found blooming in near-monoculture along a rural roadside this spring in the West Virginia mountains. Identification may not get any simpler if botanists follow through on splitting the Buttercups into as many as eight different genera. Some of the Buttercups are very different--Water Crowfoots and Spearworts, for example--and grow in aquatic or damp habitats. That said, all Buttercups are more or less moisture-loving, hence the origin of the genus name Ranunculus, meaning "little frog." If we had to hazard an educated guess based on foliage and flower shape, we'd say the flower above is R. bulbosus, also known as St. Anthony's Turnip or Bulbous Buttercup--so called due to its swollen underground corm. If our ID is correct, we must divulge this eye-pleasing blossom is a non-native that originated in Europe. We also should mention all buttercups contain a toxic glycoside that causes mouth blisters when fresh foliage is eaten; fortunately, toxicity disappears when the leaves are dry--a benefit to livestock. Pollinators include bees, flies, butterflies, and small beetles.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of the most easily recognized West Virginia wildflowers is Mayapple, Podophyllum peltatum--identifiable not by its 6- to 9-petalled blossom (above) but because of two distinctive umbrella-like leaves (below) on fertile individuals. The nodding white flower forms at the leaf axil and when self-fertilized or pollinated by Bumblebees and other long-tongued bees gives rise to a juicy "apple." This green fruit is toxic but can be eaten in lesser amounts by White-tailed Deer and small mammals when yellow-ripe. Native Americans were aware of the plant's toxicity and used chopped roots as a cathartic; curiously, podophyllotoxin also can be used in a tea to remove warts.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Mayapple is a herbaceous perennial native to deciduous forests of eastern North America, where it will not survive unless certain mycorrhizal fungi cohabit the soil around its roots. These fungi penetrate the plant's root cells and transfer water and soil nutrients to the host, which--in turn--provides photosynthetic sugars to the fungus. Such obligate symbiotic relationships occur with numerous wild plants, one reason why transplanting them from natural habitats to backyard gardens often fails miserably. (HINT: Don't try to dig and transplant any wild flora unless they are in danger. If you want wildflowers in your yard, grow them from seed or order cultivated plants from a reputable native plant nursery.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center And speaking of symbiotic relationships, down a mountain trail we found an example of commensalism, in which two plants were growing together with no particular influence or advantage on one another. In this case an unidentified white violet, Viola sp., had taken root in a bark crevice of an old hardwood tree about a foot above the substrate. The crack undoubtedly contained organic material--decaying bark, dead mosses, old leaves, etc.--all of which provided nutrients for the violet. Although normally found growing on soil, this particular individual was essentially an epiphyte--just like bromeliads and orchids in the tropics that only use their "host" tree for physical support. (NOTE: If you can identify the white violet in our photo, please e-mail the I.D. to INFO.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Not far from the tree-dwelling white violet was one much easier to identify (above). First, it was yellow, and we know of only four violets of this hue in West Virginia. And, second, it bore unusual spear-shaped leaves. (Most violets have rounded, heart-shaped foliage.) This plant was Halberd-leafed Violet, Viola hastata, a native perennial that flowers from early to mid-spring. (A halberd is a combined spear and battle-ax used by Medieval soldiers.) This species also has erect blossoms, while most violets bear inflorescence close to the the ground on shorter stalks. Having tall flowers may allow this species to get its bloom above whatever snow cover remains as winter turns to spring; if nothing else, the flower rises above leaf litter in the hardwood forest. Foliage color among Halberd-leafed Violets seems to be highly variable, with some individuals sporting variegated leaves in two or more shades of green. We suspect Halberd-leafed Violets are pollinated by small, metallic green Mason Bees. Note that this yellow-flowered violet--like the white one preceding--also has "bee guides," but just on the lower petal.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The was no question a small unidentified native bee was pollinating our final West Virginia wildflower (above)--a Daisy Fleabane, Erigeron anuus. This native species is almost ubiquitous in North America, occurring in 43 of the 48 contiguous states plus southern Canada. As the species suggests, it is usually an annual but also occurs as a biennial, making a basal rosette one year and flowering the next. This is a member of the Sunflower or Aster Family (Asteraceae) in which the inflorescence is actually comprised of two kinds of flowers: 1) Outer showy "ray flowers" that are sterile and serve to attract insects; and, 2) central yellow flowers "disk flowers" that produce seeds. Three-quarter-inch-flowered Daisy Fleabane resembles the much-larger Oxeye Daisy but has many more ray flowers. These are usually white but do occur in a pale pink or lavender as in our photo above. (NOTE: If you happen to know the name of the bee in the photo, please send an e-mail to INFO.) With Ernesto riding shotgun on 7 May, we steered our passenger van from West Virginia's New River Birding and Nature Festival in time to return to South Carolina for Mother's Day--such holidays being important. Then it was down to business deploying mist nets and sunflower seed traps so we could band birds at Hilton Pond Center, a task that's always easier when two people are involved.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As usual, we missed the peak of Piedmont Carolina's spring migration by being in the Mountain State, but there were still birds to be caught at the Center. Among them was a brightly colored male Blue Grosbeak (above), with deep blue head and body, bi-colored bill, and rusty shoulder patches--the latter being absent from the similarly colored but much smaller male Indigo Bunting we also captured during May's second week. In the net with the male grosbeak was a female, whose mousy gray-brown colors make her a species new birders often have trouble identifying. We weren't surprised to catch both grosbeak sexes in the same net at the same time; the species nests at Hilton Pond in May so the two were probably involved in a courtship chase.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The second week in June we netted another species at Hilton Pond Center in which the female is much drabber than the male, in this case the American Redstart. Males are "Halloween birds," with orange tail spots and shoulders and jet black feathers in place of the gray-green ones shown by the female above. This species also breeds locally; for two consecutive years what must have been the same banded pair nested in a Common Persimmon tree down by the pond.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One species Ernesto helped band at the Center definitely does not breed in the Carolina Piedmont and must have been passing through on its way to a nesting site somewhere from West Virginia north to Alaska and across most of Canada. This was a Northern Waterthrush (NOWA above). We catch a good number of these birds on our Operation RubyThroat study sites in the Neotropics and even have some returns in Costa Rica where NOWA overwinter. Although waterthrushes with their brown backs and streaked breasts scarcely resemble their bright yellow relatives in the Wood Warbler Family (Parulidae), that's where they and the equally brown Ovenbird are classified. (Note the buffy eye line and streaked throat in the bird in the photo above. We'll explain why those are important field marks later on in this photo essay.) The Northern Waterthrushes departed Hilton Pond Center on or about 13 May, which was also the day we took Ernesto to the Charlotte airport. We always feel a little sad when our Costa Rican guide and colleague leaves us, but this time we were pleased he was heading for St. Louis rather than his home in Paraíso. Seems he was invited to give several presentations to Missouri birding groups about his ground-breaking work with Cerulean Warblers migrating through Costa Rica. That comment segues into an interesting sighting of a species seldom encountered at Hilton Pond: Mississippi Kite. Our first local experience with this Neotropical migrant was in August 1984 when biology student Russ Rogers spotted a juvenile perched in a tree near the edge of the pond. Our next encounter was May 2015--32 years later--when 'Nesto was visiting and pointed out a pair hovering in the distance as we stood on the road in front of the Center. This year an adult in unmistakable two-tone gray plumage was circling directly overhead our office the day after Ernesto departed--14 May, which appropriately enough also happened to be to be International Migratory Bird Day. We suspect this species is nesting close by, an apparent extension of its historical breeding range that included the South Carolina Lowcountry.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center On 16 May we took the floating dock (aka U.S.S. Hilton) out on the pond to check our four Wood Duck boxes for any remaining activity. Two showed no sign of being used since 2015. One box known to be active earlier this year contained a lot of duck down and egg fragments, so those young all must have hatched and fledged. A fourth contained down, five un-hatched but cold eggs, and a mummified recent hatchling that somehow perished; we suspect this box did produce at least a few viable offspring. Since 1982 these four boxes on Hilton Pond (and two others on an adjoining pond) have yielded more than 700 Wood Ducklings. Each box also contained at least one active nest of Paper Wasps (above); opening a nest box access door led to one of the irritated insects stinging the resident bird bander on the forearm. This is never good news for one who is hypersensitive to insect stings, so yours truly paddled back to shore as fast as possible and went for the Epipen, which worked as usual. (NOTE: As a naturalist, Bill Hilton Jr. has no desire to succumb to anaphylactic shock caused by an inch-long female wasp he had no intention of harming.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We doubt our banded House Finch (HOFI) numbers at the Center likely will again reach the stratospheric numbers of the early 1990s when we banded 1,973 in a three-year period--compared to a mere 255 in 2004-05. Many birds in the 80s and 90s were apparently migrants from northeastern states, but those northerly populations appear to have settled down and become much more sedentary. At the same time, the number of breeding pairs of House Finches in the Carolina Piedmont has dramatically increased, and now it's not uncommon for us to band a dozen or more recently fledged finches in one day at Hilton Pond Center. Such was the case in May this year when 81 HOFI crossed the banding table, indicating this is by far the most prolific nesting species at and around the Center. By the third week of the month some fledgling House Finches bore evidence they were gorging on something other than sunflower seeds from our multiple feeders. Indeed, these hungry youngsters had red stains on their bills and facial feathers (above)--a telltale sign they had been taking advantage of the local mulberry crop. (Note also the prominent yellow-orange "gape" on the finch in the photo; this is typical of young birds.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Several species of mulberry trees are producing abundant fruit at Hilton Pond Center and around the neighborhood; some are imported cultivars, but the native Red Mulberry, Morus rubra (above), is among the most prolific. This year all our female mulberry trees are laden more than usual--male trees do not bear fruit--and we've been battling House Finches, Eastern Bluebirds, and Eastern Gray Squirrels to get our fair share of the tasty achenes.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although we did trap lots of House Finches in May, we didn't have many opportunities to run mist nets during the last half of the month. Thus we were pleased to end the period on a high note on 31 May. The tally was nicely diverse for this time of year--three kinds of flycatchers, for example--and some of the 13 species (23 individuals) were birds we seldom handle. Two captures were Downy Woodpeckers, and even though this species isn't particularly unusual at the Center we include the image above to illustrate something interesting about the bird's plumage. Whereas an adult male downy has red on his nape, a nestling or fledgling male--as the photo reveals--typically has red on the crown. We speculate this helps parent Downy Woodpeckers see their male chicks better in the dim light of a cavity. Since male nestlings are often more aggressive than their sisters, the male youngster's red spot may help adults assure they identify and pay appropriate attention to the needs of female offspring. That's just a hypothesis, of course; it could use a little field testing with a nest cam!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center If asked to select the "Banded Bird of the Day" for 31 May we would be hard-pressed to choose between Great Crested Flycatcher and Louisiana Waterthrush (LOWA, above)--the former because that species was the first identified by wife Susan Hilton when she started birding (and is still her favorite), and the latter because LOWA are seldom reported in this part of the Carolina Piedmont during the breeding season. In past years we have captured recently fledged Louisiana Waterthrushes and females with brood patches, so we're certain they are breeding locally--even though we've not found a nest. As mentioned earlier in this photo essay, the closely related Northern Waterthrush (NOWA) migrates through Hilton Pond Center in spring and fall but does not breed here, so we wouldn't expect them in late May. And while NOWA have a buffy line above the eye and (almost always) a streaked throat, our local LOWA have a white superciliary line and clear throat. Louisiana Waterthrushes are also chunkier and, in our judgment, have heavier bills. Too bad we've never found their nest. So that's it for May 2016, from West Virginia's mountains to Hilton Pond and the rolling hills of the Carolina Piedmont. Despite their obvious differences in topography, the two provinces share many species--especially resourceful birds (and Ernesto M. Carman) who wing their way to and from Fayette County WV and York SC during migrations north and south. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

Checks can be sent to Hilton Pond Center at: All contributions are tax-deductible on your |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

Comments or questions about this week's installment? Send an E-mail to INFO. (Be sure to scroll down for a tally of birds banded/recaptured during the period, plus other nature notes.) |

WHEN IT'S DREARY AND COLD

WHEN IT'S DREARY AND COLD Up in the mountains each spring we've been part of the

Up in the mountains each spring we've been part of the

It's always extremely satisfying to watch a talented protégé spread his or her wings in this way and soar to new heights.

It's always extremely satisfying to watch a talented protégé spread his or her wings in this way and soar to new heights.

Please report your spring, summer &

Please report your spring, summer &