|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

Come be part of a real |

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center ROBINS OF AUTUMN October is a time of big change at Hilton Pond Center, especially with the departure of all those Ruby-throated Hummingbirds that hung out locally or passed through the property. We banded our last one on 12 October--our third-ever latest. Now we'll stow most of our hummingbird feeders and traps--leaving a few, of course, in the hope of getting one of those winter vagrant hummers from out west. (We've hosted two Rufous hummingbirds through the years.) Except for chasing hummingbirds in Costa Rica in November 2016 and Belize next March, we'll just sit back and wait for ruby-throats to come back in early April. Returning hummingbirds will indicate winter's end for most folks, with those tiny birds and American Robins being true harbingers of spring. At Hilton Pond, however, robins are more likely birds of AUTUMN, with dozens of these appropriately attired orange-and-black thrushes flocking in just before Halloween each year.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We do see American Robins (AMRO) across the Carolina Piedmont each spring, but most will have been hanging out here all winter in big assemblages. Around these parts robin groups start out "smaller" in October--a bunch of three dozen or so showed up at the Center just before this month's end (see top photo)--but may swell to a nomadic crowd of several thousand. (We always look for that big flock of wandering AMRO for the York/Rock Hill Christmas Bird Count in the hope of swelling our final tally.) As usual, this week's robins appeared at all three water features just outside the Center's old farmhouse, drinking and splashing about (above). Bird baths are excellent attractants for American Robins; in fact, a trap baited only with dripping water is a time-honored way to catch them for banding.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The American Robin, Turdus migratorius, was named by early settlers familiar with the European Robin, Erithacus rubecula (above). Both species have bright reddish-orange breasts, but there the similarity stops. American Robins are in the Thrush Family (Turdidae), while European Robins are actually Old World Flycatchers (Muscicapidae). Bird taxonomy is in flux, however, so tune in next week to see whether DNA studies have figured out the "real" relationship between thrushes, flycatchers, kinglets, and Old World Warblers. Although American Robins don't catch flies they are essentially omnivorous, eating all sorts of invertebrates (beetles, grubs, caterpillars, grasshoppers, earthworms, etc.), with a penchant for berries and other fruit--especially during cold weather when animal prey may be harder to find. Despite the species' reputation as a champion worm-hunter, about 60% of a robin's diet comes from plants. AMRO also fit the natural--and unnatural--food chains as prey items themselves, serving as dinner for accipiter hawks and far too many feral and free-roaming House Cats that find easy pickings on suburban lawns providing little protective shelter. Robin eggs and chicks are taken by arboreal snakes, squirrels, and songbirds such as jays, grackles, and crows. It's also worth repeating this note we got from outdoorsman friend Jim Casada:

All text, maps, charts & photo s© Hilton Pond Center American Robins are almost but not quite sexually monomorphic. Although the two sexes do look very much alike, adult males (above and below) typically have brighter breasts and a very black head contrasting sharply with a dark gray back. That means, of course, females have paler breasts, backs, and heads. There is a slight size difference, with males generally larger. There is also variation in size among what taxonomists claim are five AMRO subspecies that together cover the entire continental U.S. and Canada's southern provinces.

All text, maps, charts & photo s© Hilton Pond Center American Robin is the official bird of three states: Connecticut, Michigan, and Wisconsin, third in popularity to Northern Cardinal (seven states) and Northern Mockingbird (five states). Connecticut first considered the Ruby-crowned Kinglet but in 1943 finally went with AMRO.

All text, maps, charts & photo s© Hilton Pond Center At first glance American Robins appear to have much larger eyes than similarly sized birds, but this is likely because of contrast with a large irregularly shaped white eye ring (above). Equally visible in the close-up photo is the robin's bright yellow gape--the soft area at the corner of upper and lower mandible. Yellow gapes are typical of younger birds of many species (a photo below of nestlings shows this), but AMRO retain this characteristic in adults. Robins also have prominent rictal bristles--stiff modified feathers that don't seem to function like touch-sensitive cat whiskers; instead the bristles probably protect a robin's eye as it tries to swallow squirmy worms and boisterous beetles.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center And speaking of the American Robin's oral cavity (above), closer examination shows even more adaptations for consuming food. The long arrowhead-shaped tongue--which is not associated with singing--is attached to the floor of the mouth, but each side of the base is free and pointed toward the rear. This, in conjunction with small rear-facing spines (shown near the tongue base above), all help keep live prey from crawling back out prior to swallowing. (Barbs in the roof of the upper mandible assist in the same way.) Finally, the tip of the robin's bill is notched, making it "raptorial"--all the better to hold onto mobile inverts that might otherwise get away.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Among American Robins, the female constructs a nest (above) essentially by herself. After settling on an appropriate spot--anything from a porch column to a sturdy branch--she builds a foundation and main cup out of mud reinforced by long grasses, flexible twigs, and other plant matter. It's not uncommon to find string, yarn, paper, and other human-made artifacts in a robin nest, so these birds do us humans a favor by picking up litter. (NOTE: Long strings may be hazardous to both adult birds and nestlings that can become entangled. If you put strings out as nesting material for robins and other birds, cut them into short lengths of about 4".) We've found nests for AMRO several times at Hilton Pond Center through the years, usually on large horizontal tree limbs.

When the female assumes incubation duties her task is facilitated by development of a prominent "incubation patch" (also called "brood patch"; see photo at right). This structure forms as the female's breast and belly feathers are lost, assuring direct contact between eggs and her body without insulating plumage getting in the way. The patch's efficiency is enhanced when her belly becomes vascularized with blood vessels that bring more body heat, and when her skin becomes edematous--i.e., filled with fluid that essentially makes the brood patch a highly efficient hot water bottle. (NOTE: Although the male robin is known to sit on the nest during short breaks by the female, he does not develop a brood patch. He is likely insulating rather than incubating, not adding heat but protecting eggs against heat loss.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After chicks hatch the male joins his mate in gathering food for their ravenous brood. One source speculates a pair of adult American Robins feeds each nestling up to 14 feet (168 inches) of earthworms per day. A typical earthworm is 3" long, meaning 56 worms per chick. Assuming one earthworm per visit, that's a minimum of 168 visits per day for a nest with three chicks that take 12-14 days to fledge. When we consider that American Robins typically double- or even triple-brood in a given season, that's a heckuva lot of worms and visits. Whew!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We like to refer to the Turdidae as the "Spot-breasted Thrushes because its members have that characteristic--at least in juvenal plumage. These North American thrushes include, among others, Swainson's Thrush and Veery (which are spotted as adults) and the three bluebirds (like the young robin, above, spotted only as nestlings and recent fledglings).

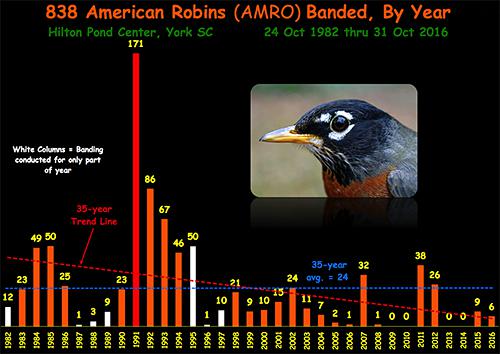

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center American Robins were more common at Hilton Pond Center from 1982 through the mid-1990s (see chart above) when our 11-acre property was much more open and still in early stages of vegetational succession. Back then, more grassy areas meant more foraging sites for the robins. By the late 1990s shrubs and small trees had taken over AND--to make matters worse--West Nile Virus was detected in North America. AMRO were plentiful and amply sized avian targets for mosquitoes carrying the disease. We suspect there was significant robin die-off during those early years of the epidemic, but now this species has reportedly become more WNV-tolerant than many of our native songbirds.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Of our 838 banded American Robins (check out the size 2 band on the bird just above), a few have returned to Hilton Pond Center in later years but just two have been encountered elsewhere. One, an adult of undetermined sex banded 7 Feb 1992, was found dead almost exactly two months later in Pittsford NY, about 600 miles northeast of Hilton Pond. This bird undoubtedly overwintered in our area and was still heading north or already on its breeding grounds when found. A second AMRO fared somewhat better. Banded here as a recent fledgling of unknown sex on 9 August 1995, this individual was found dead nearly six years later on 29 May 2000 in Charlotte NC. According to the U.S. federal Bird Banding Laboratory the longevity record for a wild American Robin was 13 years 11 months (in California), so our venerable Hilton Pond/Charlotte bird was still well short of this mark. Since Charlotte is only 30 miles away, we suspect this robin merely dispersed from its natal grounds and took up residence just over the border in North Carolina. This kind of banding info is always interesting and quite valuable in helping ornithologists understand the behavior and ecology of native birds. Thus, we're quite pleased there are plenty of American Robins flocking to Hilton Pond right now. Whether we catch them for banding or not, they're still one of our favorite and most obvious avian indicators that autumn has finally arrived here in the Carolina Piedmont. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

Checks can be sent to Hilton Pond Center at: All contributions are tax-deductible on your |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

Comments or questions about this week's installment? Send an E-mail to INFO. (Be sure to scroll down for a tally of birds banded/recaptured during the period, plus other nature notes.) |

WHEN IT'S DREARY & COLD

WHEN IT'S DREARY & COLD

A clutch typically contains 3-5 oval and unmarked blue eggs that take about 14 days to hatch. Incubation does not begin until the full clutch is laid, assuring that all chicks hatch synchronously, i.e., at about the same time.

A clutch typically contains 3-5 oval and unmarked blue eggs that take about 14 days to hatch. Incubation does not begin until the full clutch is laid, assuring that all chicks hatch synchronously, i.e., at about the same time.

Please report your spring, summer &

Please report your spring, summer & Oct 15 to Mar 15:

Oct 15 to Mar 15: