|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

11-19 Nov 2017 & 20-28-Jan 2018 Come be part of a real |

BIRD EGGS (Part 1): No one is quite sure when rabbits and eggs became associated with the Easter season, but it likely has something to do with being re-born in spring. That, in itself, seems a little odd because rabbits are viviparous mammals, birthing their young alive rather than laying eggs. Despite mammalian viviparity lots of other vertebrates do lay eggs, of course, and have external development of their young; these include fish and amphibians that deposit gelatinous eggs in water, reptiles that lay leathery eggs on land, and birds that frequently place hard-shelled eggs into nests in diverse terrestrial habitats. Satisfying and entertaining as the rabbit/egg myth may be, egg production in birds is in reality a fascinating process--as we were reminded this week at Hilton Pond Center.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center During warm weather months at the Center we deploy mist nets to capture wild birds for banding; especially in winter we also operate traps baited with cracked corn, millet, sunflower seeds, and other bird attractants. Because neither nets nor traps are selective we never know what we might capture. This week, for example, we netted a passel of (i.e., 18) migrant White-throated Sparrows while trapping a slew of (224) American Goldfinches and a skosh of (six) Brown-headed Cowbirds (female above). It was one of the cowbirds that got us to thinking again about bird eggs and how they are formed.

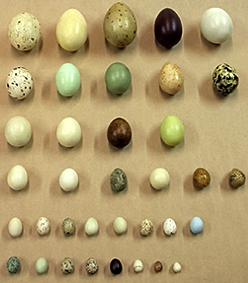

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Cowbirds are like other birds in that a male provides sperm when he copulates with a female; shortly thereafter fertilization occurs internally in the female's oviduct and eventually she lays the fertile egg in her nest. Cowbirds, however, are different from most of their avian relatives because they are brood parasites. Rather than building a nest herself the female cowbird places her fertilized egg in another bird's domicile, leaving the chosen set of foster parents to raise her young. (A single Red-eyed Vireo egg in a hanging nest, above, is somewhat dwarfed by TWO Brown-headed Cowbird eggs, probably from different cowbirds.) Cowbirds have maximized this adaptation, with some reports stating an individual female lays up to 12 eggs to start. After taking a short break she can then recharge her reproductive tract and lay 12 more AND do this yet again for a phenomenal total of 36 eggs. That's 36 commandeered foster nests in just one breeding season. Even if only a documented 3% of these eggs result in adults, it's not surprising Brown-headed Cowbirds have had significant negative impact on breeding success of many species they parasitize--especially since host-family chicks often die when they are out-competed by more aggressive faux-sibling cowbirds.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Most songbirds are much less prolific than cowbirds in the first place. Through the years, a typical Eastern Bluebird female at Hilton Pond Center has laid 5 eggs (rarely six, above) before starting to incubate; if their first clutch is successful an established bluebird pair may try again with 3-4 eggs--or even a third time with 2-3. And one other note: To our knowledge all songbirds are "altricial," meaning their chicks are born blind, essentially naked (unable to thermoregulate), and totally dependent on one or both parents for warmth, protection, and food. Many non-passerines--including waterfowl--have "precocial" young that hatch covered by down and ready to run or swim. Fledgling Wood Ducklings (above left) don't require much care from their mother after she calls them from the nest and leads them to water; they get no attention from the drake.

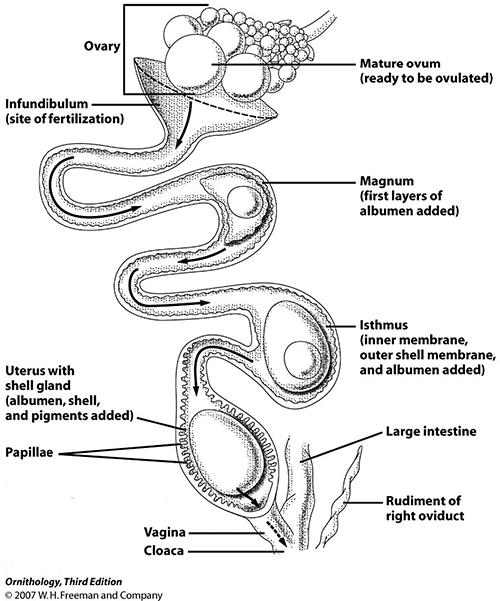

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center All the above is interesting, but if the bunny doesn't bring bird eggs just where DO they really come from? In explanation we refer you to the drawing above, representative of a female bird's reproductive tract. But first, a caveat: Many female birds can produce eggs without a male; if a female's hormones reach the right level, she may begin laying without stimulation from a partner. Those eggs would be infertile, of course, as happens in the hen house when no rooster is present.

Newly liberated sperm swim all the way up the oviduct to the ovary, where ripening ova (unfertilized eggs; singular is "ovum") receive yellow, fat- and protein-rich yolk material. Actual ovulation and subsequent fertilization occur in the infundibulum, a funnel-like structure that catches the fertile egg and directs it into the oviduct itself. The egg then passes through the magnum, where first layers of albumen (liquid egg white) form around the yolk. Albumen is about 90% water--which helps prevent desiccation--the remainder being essential vitamins, minerals, glucose, fats, and protein. Further down the oviduct a structure called the isthmus produces more albumen, plus an inner membrane and the outer shell membrane. Actual development of a bird embryo does not begin until heat is applied, i.e., when incubation starts. Songbirds don't typically incubate until the full clutch is laid, guaranteeing a more or less synchronous hatch and even-aged nestlings. Other species--some raptors, for example--begin incubating when the first egg is laid, meaning a second hatchling would be younger than its sibling. (In a raptor that lays an egg and skips a day before laying another, a five-day-younger third chick might eventually be known as "lunch.") And one final note of interest: Careful review of the drawing above shows a "rudimentary" right oviduct. That's because in most female birds only the LEFT side of the bilateral reproductive system is developed and active. This is an obvious adaptation for flight; no sense having both ovaries functioning and adding weight when one will do just fine. (Amazingly, there are accounts of a bird's vestigial right oviduct springing into action after the left one had been damaged!)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We've always been fascinated by bird eggs and how they are produced, but what--you might ask--does all this have to do with the Brown-headed Cowbird we caught this week at Hilton Pond Center? Well, here's what actually happened. One morning we spotted this female cowbird in one of our automatic traps and went out to remove her for banding. As we reached in to gently grasp the bird, her excitement must have gotten the best of her because she laid an egg in the trap (above). This egg apparently was just beginning to develop its calcified shell and was still quite flexible, sort of like a water balloon. It likely would have taken several more hours before the shell was completely hardened, but for the moment we could see a yolk though the outer membrane and albumen. It was a ghostly, almost mystical egg, and somewhere inside was an ill-fated embryo waiting for foster parents that wouldn't have to raise this baby cowbird. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Don't forget to scroll down for Nature Notes & Photos,

Checks can be sent to Hilton Pond Center at: All contributions are tax-deductible on your |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

Comments or questions about this week's installment? Send an E-mail to INFO. (Be sure to scroll down for a tally of birds banded/recaptured during the period, plus other nature notes.) |

JUST ANNOUNCED!

JUST ANNOUNCED!

Our Carolina Chickadees typically have 6-7 eggs

Our Carolina Chickadees typically have 6-7 eggs

Assuming there IS a male bird, he and the female copulate, albeit briefly. When the male mounts the female she turns her tail to the side and twists her cloaca upward

Assuming there IS a male bird, he and the female copulate, albeit briefly. When the male mounts the female she turns her tail to the side and twists her cloaca upward  The last stop is the uterus, where still more albumen is made and a shell gland lays down calcium that may or may not be pigmented.

The last stop is the uterus, where still more albumen is made and a shell gland lays down calcium that may or may not be pigmented.

Please report your

Please report your