- Established 1982 -HOME: www.hiltonpond.org

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center BULL THISTLE: If you've ever walked bare-legged through an old field infested with thistle (above), you probably came out with multiple scratches on calves and thighs and a genuine dislike for these prolific weedy plants with sharply spined leaves. ("Thistle" comes from the Dutch word distel, meaning "something sharp." It's an appropriate description for a plant with a leaf, below, that looks like some sort of Medieval torture device.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center And if you happen to be a farmer, you REALLY don't like spiny thistle that can out-compete crops like hay and corn and cut the mouths and udders of grazing cattle. Despite these minuses, thistles play an important ecological role as food sources for wide variety of native animals from bees to birds and mice to butterflies.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Let an old field around Hilton Pond Center lie fallow for a year or two and windblown thistle seeds--technically, achenes--are likely to arrive and sprout. Thistles can be annual or biennial. Annual varieties complete their life cycle within the same year, while in biennials a seed germinates in summer or early autumn before forming a ground-hugging rosette of leaves (above) that lasts the winter. Come spring the biennial thistle sends up a stalk bearing much spikier leaves followed by those familiar purple or pink flower heads. A few native thistles occur in the Carolina Piedmont--including a yellow one--but most commonly encountered here is non-native Bull Thistle, Cirsium vulgare (aka Spear Thistle), that typically grows along roadsides and in waste areas. Here at Hilton Pond Center we have a scattering of Bull Thistles that grow only in small open areas we cut and maintain as "false meadows," or along the road frontage where seeds likely get concentrated by highway department mowers and other equipment. Sun-loving plants, thistles don't fare well along the Center's tree-shaded trails. It's a surprise to many folks that thistles are in the Composite Family (Asteraceae, aka Compositae), actually making them one of the "sunflowers." As is true for several members of this family, the long tap root of Bull Thistle is edible to humans either boiled, baked, or fried. In nature it's eaten raw by burrowing rodents such as voles.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center This year our tallest and most prolific Bull Thistle is growing on the east-facing road shoulder in front of the Center's old farmhouse, fully exposed to direct sunlight for much of the day. Reaching a height of nearly six feet, it started flowering around the first of July and through month's end produced at least 50 colorful flower heads (above).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As with disk-shaped sunflowers, the two-inch-diameter flower head of Bull Thistle is comprised of many florets (above), each with its own complement of pistil and stamens. Upon fertilization, the floret makes a tiny seed to which is attached a gossamer plume; this enables the seed to float on the wind, providing for dissemination away from its mother plant.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center With all those individual florets pumping out nectar, one might expect lots of insect nectarivores to visit Bull Thistle, and this is certainly the case. In particular, the plant is attractive to Long-tongued Bees (including Bumblebees), Cuckoo-bees, and Leaf-cutting Bees, plus several butterfly species--especially swallowtails and skippers. Long probosces of all these, including the somewhat tattered Silver-spotted Skipper, Epargyreus clarus (above), allow them to probe deeply into thistle florets. And lest we forget, we have indeed observed Ruby-throated Hummingbirds lapping up Bull Thistle nectar in early summer.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Halictid Bees such as Bi-colored Sweat Bee, Agapostemon virescens (above), frequent Bull Thistle for edible pollen; however, they lack hairy bodies or pollen baskets and don't serve as pollinators like the nectar-probers. (FACTOID: The Bi-colored Sweat Bee is the Official Bee of Toronto, Canada. Who knew?) And even though Bull Thistle is an exotic species, native Painted Lady butterflies lay eggs on the plant and their caterpillars munch on its foliage.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Among the more interesting insect assemblages we discovered on Bull Thistles at Hilton Pond Center were entire "families" of Eastern Leaf-footed Bugs, Leptoglossus phyllopus (adults and first instar nymphs, above). This insect gets its name because of a large, flattened "leafy" tibia on the adult's hind leg.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In early July we found only adult bugs on thistle, but by mid-month some thistle heads were practically covered by little orange-and-black nymphs (above); by month's end those immature bugs had gone through several molts and had doubled or tripled in size (below).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Amazingly, it takes only 25-30 days for Eastern Leaf-footed Bug nymphs to complete five instar stages (first and third instars above), with the nymph molting its entire exoskeleton between each instar. By the fifth instar (below), wing buds are becoming prominent. Adults are long-lived and survive all winter in temperate areas; they are strong fliers and may cover considerable distances to find host plants.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As True Bugs (Hemiptera), both nymphs and adults have impressively long, needle-like mouth-parts adapted for piercing and sucking plant juices (see photo below). Although the species we found occurs frequently on thistles, it is apparently a generalist that feeds on many kinds of plant. It is considered an agricultural pest because of primarily cosmetic damage to diverse crops including but not limited to peaches, tomatoes, cotton, beans, pecans, corn, and ornamentals.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Unfortunately, few biological controls are known for Eastern Leaf-footed Bugs--a specific gall fly is one--and they're avoided by birds and mammalian predators because they emit a foul stinkbug-like odor. Without natural help, farmers are often forced to use insecticides during major crop infestations. The best control for these bugs is probably to remove any thistles growing in agricultural settings, thereby relieving two problems at once.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We were amazed at the variety of insects frequenting Bull Thistle while we observed and photographed the flowers at Hilton Pond. With so many creatures seeking nectar and/or pollen, it's not surprising a predator like the female Goldenrod Crab Spider, Misumena vatia (above) might be lurking. This species--which varies in color from white to yellow to pink--hangs out on large flowers, waiting for some unsuspecting bee or butterfly to flutter by. Then, in a flash, the spider grabs the prey with its front legs, pulls it toward its mouth, and injects toxin with its formidable fangs. The hapless insect is almost instantly paralyzed or killed, after which the spider can dine in leisurely fashion. (NOTE: Male crab spiders are much smaller than females, and neither sex builds a web--opting instead to lie in ambush for the next meal.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Again, that big Bull Thistle on the Hilton Pond Center roadside formed 50-plus flower heads--each capable of producing 250 seeds--meaning just that individual plant is theoretically capable of disseminating 12,000 seeds! It's no wonder this species might take over a pasture in a few short years.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center By the end of July this year, leaves on the Center's Bull Thistles had begun to wilt and turn yellow; flowering was essentially finished and insect visits had diminished greatly, with only a few nymphal leaf-footed bug still waiting to mature. The compact pink flower heads were replaced by big clusters of seeds with fuzzy white plumes (above and below) that needed only a gust of August wind to send them floating away to a good spot. If a seed lands in a suitable crack in the soil, it's just a matter of time until autumn rainfall moistens the seed coat and stimulates germination. After that a new winter rosette will grow and rest until next summer when--as days lengthen--the Bull Thistle stem shoots skyward. The cycle begins anew . . . irritating farmers and scratching our legs with spiny leaves . . . but feeding hungry insects with pollen and nectar from multiple flowers . . . and attracting birds and small rodents that feast on those plentiful, nutritious thistle seeds.

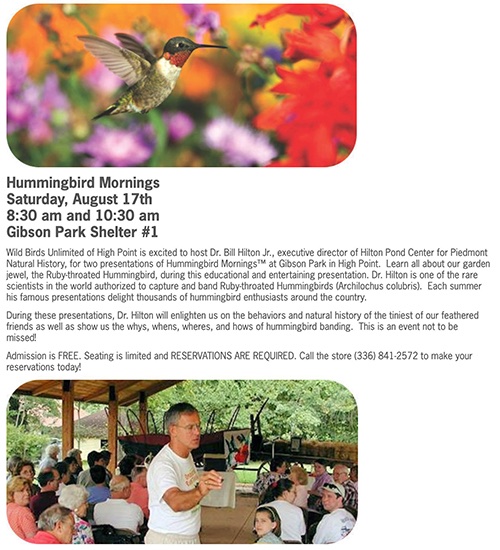

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center And so, all this deep background about a nearly ubiquitous exotic roadside weed leads us once again to pose the question: "Bull Thistles: 'Good' or 'Bad?'" For nature lovers in the Carolina Piedmont, the answer should be obvious--even if (like us) you're a native plant enthusiast. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center HUMMINGBIRD MORNINGS™ 2019 Click on the image below to open a more readable version All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

Checks also can be sent to Hilton Pond Center at: All contributions are tax-deductible on your Don't forget to scroll down for Nature Notes & Photos, |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

|

This species undoubtedly came to what is now the U.S. from Europe, its seeds hidden in agricultural products transported by early settlers. Also native to Western Asia and northwestern Africa, it is now well-established throughout North America and in parts of Africa and Australia. Bull Thistle is typically biennial but sometimes breaks the rules by flowering its first year, or even in the third or fourth summer. This is the national flower of Scotland and has appeared on various money from the British Commonwealth

This species undoubtedly came to what is now the U.S. from Europe, its seeds hidden in agricultural products transported by early settlers. Also native to Western Asia and northwestern Africa, it is now well-established throughout North America and in parts of Africa and Australia. Bull Thistle is typically biennial but sometimes breaks the rules by flowering its first year, or even in the third or fourth summer. This is the national flower of Scotland and has appeared on various money from the British Commonwealth

Although non-native, in most habitats it seems unlikely Bull Thistle will crowd out native plant species--particularly in the Carolina Piedmont. Likewise, we doubt its big showy floral display distracts pollinators from native plants that might be offering nectar and needing pollination at the same time. If you have a few thistle plants you want to get rid of, dig them up in rosette stage before they flower and make seed; the succulent and nutritious tap root

Although non-native, in most habitats it seems unlikely Bull Thistle will crowd out native plant species--particularly in the Carolina Piedmont. Likewise, we doubt its big showy floral display distracts pollinators from native plants that might be offering nectar and needing pollination at the same time. If you have a few thistle plants you want to get rid of, dig them up in rosette stage before they flower and make seed; the succulent and nutritious tap root

Not all seeds survive, of course, with many granivorous animals taking advantage of thistle's highly nutritious, protein-rich bounty. The most familiar seed-eater might be the American Goldfinch

Not all seeds survive, of course, with many granivorous animals taking advantage of thistle's highly nutritious, protein-rich bounty. The most familiar seed-eater might be the American Goldfinch

Please report your

Please report your