- Established 1982 -HOME: www.hiltonpond.org

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

Join Us for the |

|

| AUDUBON'S "CHIPPING SQUIRREL"

We've written about Eastern Chipmunks in previous installments of "This Week at Hilton Pond," but when one of these beady-eyed little "chipping squirrels" recently climbed a Flowering Dogwood just outside our office window and posed for several minutes, it only seemed appropriate to take its picture (below) and write about the species once again.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center To the best of our knowledge, Eastern Chipmunks were not present at Hilton Pond when we purchased the old farmhouse and 11-acre tract in 1982. We never observed them on the property prior to the mid-1980s when--thanks to a donation from one of our biology students at Northwestern High School--we released a half dozen specimens his parents had live-trapped at their home in Rock Hill SC. Seems the little rodents were digging up the mother's flower bulbs but she didn't have the heart to terminate them. The Center's immigrant chipmunks have done pretty well since then, yielding a now-thriving population that entertains us humans and feeds our local snakes and raptors.

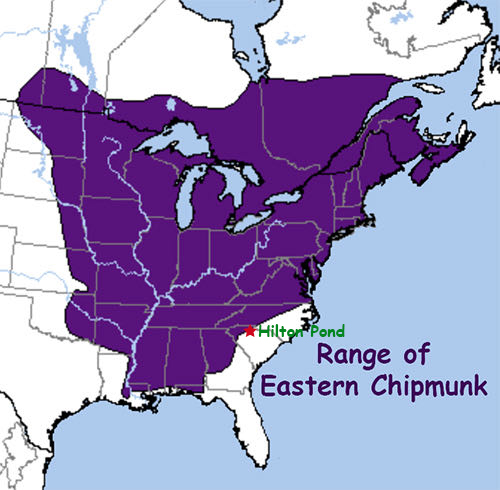

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As shown by the map above, Eastern Chipmunks have a wide North American distribution east of the Great Plans from southern Canada almost to the "fall line" in the Carolinas and Georgia. (The "fall line" is so-named because when the Atlantic Ocean came inland as far as Raleigh NC, Columbia SC, and Macon GA, waterfalls cascaded into the sea along the ancient shoreline. These days, soil from fall line to shoreline is too sandy to support chipmunk burrowing habits--hence the species' absence along the southeastern coast and in almost all of Florida.) In Upstate South Carolina, the demarcation line runs right through our home county of York, although chipmunks are occasionally reported as far south as Columbia. In his text that accompanies John James Audubon's paintings of the "Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America," the Rev. John Bachman (preacher-naturalist and founder of Newberry College) described chipmunk distribution almost exactly as above--and that was nearly 175 years ago. That the species has not appreciably extended its range since then suggests soil structure is indeed a limiting factor, as is extremely cold weather. (It will be interesting to see if Eastern Chipmunks move further north in Canada as climate change continues.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center There are 23 other chipmunk species in North America, ALL of which occur from the Great Plains westward! Although their taxonomy seems under constant review, most modern mammalogists place all ±24 chipmunk species in genus Tamias, with the Eastern Chipmunk being T. striatus. Rebellious researchers claim the western species should all be Eutamias, as with the longer-tailed Least Chipmunk (E. minimus, above, with its more heavily striped face). Incidentally, Tamias is from the Latin for "steward" or "treasurer"--from the chipmunk's hoarding behavior--while striatus pertains to its longitudinal dorsal stripes (see below).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Various rodent authorities recognize 9-11 subspecies of Eastern Chipmunk--three in the Appalachian Region. Northern individuals tend to be lighter in color, while those in the Carolinas have brighter rusty flanks as adults (above). The "type specimen" for Eastern Chipmunk was first named and cataloged by Linnaeus in 1758 from a specimen collected along the Upper Savannah River of South Carolina.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Bachman and Audubon (see his painting above) referred to Eastern Chipmunks as "Chipping Squirrels," a reference to the animals' repetitive, monotonic chuk-chuk-chuk call--usually given from some prominent ground perch within the chipmunk's territory. (Bachman also references the name "hackee," supposedly a rough imitation of the animal's chittering cry when alarmed; some linguists claim the actual word "chipmunk" is Native American in origin.) A chipmunk will indeed defend a territory vocally--sometimes violently--when interlopers intrude on its half-acre domicile. Territories often overlap, however, making for near-constant altercations among neighbors on all sides.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As noted, Eastern Chipmunks are rodents, confirmed above by a frontal view (above) of a skull showing four opposing incisors--two upper and two lower--with a long toothless diastema where additional incisors and canine teeth would be (see lateral image). Each jaw quadrant has one premolar and three molars. The incisors, of course, are adapted for gnawing, making short work of everything from hard nutshells and beetles to softer fare such as berries and earthworms; the molars then grind whatever needs to be pulverized before swallowing. Eastern Chipmunks are pretty much omnivorous and will forage, dig, and even climb for food. A particularly tasty morsel is a warm egg or half-grown chick in a nest--even an occasional adult bird if the chipmunk stalks well. (One researcher discovered ground-nesting warblers such as Veeries and Ovenbirds apparently avoid building nests in areas where they detect chipmunks vocalizing.) Two other noteworthy aspects of the skull above: The eye socket is quite large--indicating good vision--and the auditory bulla at the rear of the skull suggests sharp hearing.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center This week on one of Hilton Pond Center's trails we came across a mushroom (above) sprouting up through moist soil and noted it has been bitten into by some toothy rodent--very likely an Eastern Chipmunk. The lower wound on the mushroom reveals developing gills that give rise to spores, which are the poisonous part. Although chipmunks gorge on fungi when available, they appear to be unaffected by toxic spores.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Chipmunks--like distantly related hamsters--are well known for stuffing large quantities of food into their expansive cheek pouches (see photo of an overstuffed adult, above). At Hilton Pond, sunflower seeds spilled by birds at hanging feeders seldom stay on the ground for very long, and it's not unusual to see a half-dozen chipmunks so busy gathering seeds they have no time for intra-specific spats. The pouches truly can hold a lot of food; one enterprising observer managed to get an Eastern Chipmunk to empty its chubby cheeks of 70 sunflower seeds, while another found a chipmunk could hold 32 beechnuts! Animal rehabbers have determined an adult chipmunk needs 28 grams of food per day--about an ounce--to stay healthy. Our Eastern Chipmunks--active spring through fall--are especially industrious in early November just before cold weather sets in. After loading its cheek pouches, each chipmunk heads for its respective burrow to disgorge its treasures, typically caching in one of several side chambers; not storing the bounty in just once cache minimizes piracy by competitors that might try to raid a neighbor's larder.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center An Eastern Chipmunk's burrow is a wonder unto itself. A recently weaned youngster will often start digging not far from its mother's burrow, excavating all day long except when gathering foodstuffs. The burrow may be expanded throughout the chipmunk's life such that the final project may go down more than three feet into the earth and have several chambers and escape routes over as much as a quarter-acre. (Note the two-inch diameter entry hole at lower right in the photo above. Abundant hickory nuts and acorns indicate a richness of resources available to Hilton Pond chipmunks.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Whether Eastern Chipmunks (light-flanked autumn subadult, above) truly hibernate in their burrows is a matter of semantics. They certainly don't sleep all winter--we've seen them out and about on a warm, sunny day in January with snow cover on the ground--but they may sleep for days at a time when they lower body temperature from 100°F to 45°F. They don't put on winter fat, and after two weeks at the most they must awaken, defecate, and eat from their well-stocked caches. To us this doesn't really sound like hibernation.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We have little doubt the Eastern Chipmunk colony at Hilton Pond Center is quite fecund, The species breeds twice per year with a first litter in early spring and second in midsummer. Sexes are polygamous and promiscuous, with no long-term pair bond. After a 35-day gestation period, litters will have an average of five pups that weigh three grams each at birth--same as an adult male Ruby-throated Hummingbird. Pups (above) are are weaned at 40 days and become independent at two months, often when their mother blocks them from their natal burrow. Young chipmunks typically breed after their first winter and then live a maximum of eight years in the wild; the vast majority do not make it past a second year.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center For sure, the world is a hazardous place for chipmunks young and old, as they become lunch to a wide variety of predators. We've seen Red-shouldered Hawks at the Center swoop down and grab an unsuspecting chipmunk, and once we came across a slow-moving six-foot-long Black Ratsnake with five chipmunk-sized bumps in its sinuous body (example above). Eastern Chipmunks are also taken as food by weasels, foxes, Bobcats, and Coyotes (among other predators), while countless numbers are killed but not eaten by ever-dangerous free-roaming House Cats.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center It is not an exaggeration to say in some ecosystems prolific chipmunks are a critical part of the food chain. Even though they were absent around Hilton Pond four decades ago, these days they play multiple roles as seed scavengers, mushroom eaters, and tasty menu items for the Center's hungry hawks and serpents. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

Checks also can be sent to Hilton Pond Center at: All contributions are tax-deductible on your Don't forget to scroll down for Nature Notes & Photos, |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

|