- Established 1982 -HOME: www.hiltonpond.org

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

| A TRIP TO SWEETWATER WETLANDS PARK (Gainesville, Florida) PREFACE: For several weeks in November 2019, Lauren (Buys Holena) Shuman--wife of lifelong friend Jim Shuman, After Laurie died it was only appropriate for me to travel to Florida to spend some quality time with Jim, --BILL HILTON JR.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The speedy 480-mile road trip from Hilton Pond Center to Ocala FL took right at eight hours, bypassing Columbia SC, Savannah GA, and Jacksonville FL. The "trip list" was almost uneventful, with only a Bald Eagle to complement hundreds and hundreds of Turkey Vultures and a few other common species seen along the way. Approaching Ocala we passed through vast fenced grasslands (above)--once home to herds of beef cattle and now the breeding grounds for thoroughbred horses. (Apparently it's not uncommon at Ocala International Airport to see wealthy sheiks boarding private aircraft with Florida stallions that have potential to outrace other steeds back on the Arabian Peninsula.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Jim and Laurie Shuman moved about two years ago to On Top Of The World, a retirement community developed on one of those old cattle farms near Ocala. Jim got involved in the Astronomy Club and the Birding Club, so he's becoming quite familiar with outdoor sites in north-central Florida. A prime natural history spot, he has learned, is 125-acre Sweetwater Wetlands Park (aerial above) south of Gainesville.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Even without countless birds it attracts, this facility is an eye-pleasing wonder, with beautifully constructed paths, bridges, and boardwalks (above) that meander through diverse habitats such as open-water lagoons (elevation ~61'), Water Hyacinth pools, cattail marshes, flooded scrub oaks, Palmetto/Eastern Red Cedar hammocks (elevation ~63', below), and Longleaf Pine/Baldcypress "uplands" (elevation ~66'). In Florida, elevation changes of just a few feet--as we estimated from Google Earth--can make a world of ecological difference!

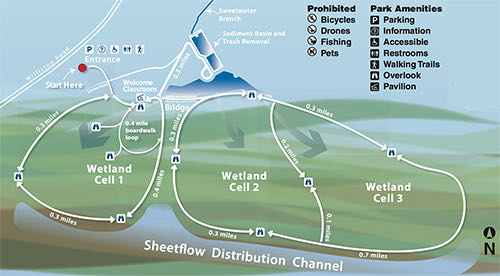

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Water that flows through Sweetwater leaves the Gainesville wastewater treatment plant in pretty good shape, with final holding ponds (just upstream from the wetlands) preventing intrusion by sediment and floating run-off litter. Aquatic and emergent vegetation within Sweetwater Park filters other organic and inorganic compounds before releasing nearly pure water into adjoining Paynes Prairie Reserve State Park, an enormous 21,000-acre wet savanna that is home to 300 bird species, wild horses, and even a small herd of American Bison. From there fresh water exits as sheetflow and eventually enters underground aquifers--all-important sources of drinking water for this part of Florida. The overall project includes filling in Sweetwater canal that once drained the wetland for grazing; such canals criss-cross Florida, creating environmental problems whose adverse impact land managers are finally beginning to comprehend and rectify. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center CLICK ON IMAGE ABOVE TO OPEN A LARGER MAP Sweetwater Wetlands Park itself is a new initiative that opened in May 2015. Although quite new, it is already a haven for birds and wildlife from endangered Snail Kites to American Alligators. With some new bird or plant appearing at nearly every turn in the path, it's virtually impossible for a birder/botanist/nature photographer to cover in one day the park's three-plus miles of trails (see map above). Nonetheless, we headed out on the Boardwalk Loop to see how far we could go and were delighted to tally a long-billed, spotted Limpkin (below) as our first wetland bird species of the day.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We have seen Limpkins (above) many times in Belize but seldom in the continental U.S., mostly because they are limited primarily to Florida. (Oddly, two REALLY out-of-range Limpkins were reported this year from Ohio; a few other individuals are spotted annually in other states.) This species was nearly extirpated from the Sunshine State in the early 20th century due to over-hunting and habitat loss but made a nice comeback after new conservation laws were passed and enforced.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although Limpkins can use their strong, slightly decurved bills to pry open bivalve mollusks, they seem to relish stabbing large apple snails--four species of which are found in Florida (one native, three exotic from Central and South America). The native Florida Apple Snail, Pomacea paludosa--with a blunt tip to its whorled univalve shell--apparently does not occur at Sweetwater. Instead, the wetlands now support an invasive population of Island Apple Snail, P. maculata (formerly P. insularum), above. We learned from Rex Rowan of Alachua Audubon that this snail "boomed in the flooding that followed Hurricane Irma in 2017, and they're entirely responsible for the large number of Limpkins."

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center An even greater beneficiary of the Island Apple Snail invasion has been the Snail Kite, a medium-sized raptor with 3.5-foot wingspan. Adult males are gray and black, while immatures and females are brown with dark ventral streaking. Because of its buffy superciliary patch and throat, we suspect the individual in our Sweetwater photo above was a young bird-of-the-year. Note the sharply hooked bill that allows the kite to pry open an apple snail's operculum to get at meat within. Also visible is a white rump patch that sometimes leads observers to misidentify Snail Kites as Northern Harriers (aka Marsh Hawks), which are slightly larger and tend to wobble in flight. Rex Rowan relates some astounding information: The local population of Snail Kites around Sweetwater "began with a single bird in February 2018 [post-Hurricane Irma], with the latest 2019 Christmas Bird Count tallying 99!"

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of the most distinctive birds at Sweetwater is the Anhinga, sometimes called Water Turkey, Darter, or Snakebird--the latter epithet coming from its habit of swimming along with body submerged and only its head, bill, and sinuous neck protruding. (Some etymologists claim the word "Anhinga" comes from the Portuguese, but we think this is an egocentric view; Tupi Guarani Indians of Brazil reportedly used a similar word for the species long before sailors from Portugal colonized that South American country.) Anhingas are in the same bird order as frigatebirds, gannets, boobies, and cormorants (Suliformes); because males have inflatable, more-or-less colorful throat pouches, all these were once classified in the Pelicaniformes, but DNA studies reveal their genetic differences are too great.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another apparent misunderstanding about Anhingas pertains to their habit of spreading wings after emerging from the water. It was long thought these birds lack a uropygial gland at the dorsal base of the tail that provides oil with which most birds apply waterproofing to their plumage; without such oil, they needed to spread their wings to dry out. However, the uropygium is clearly visible in our photo above of an Anhinga sunning on a bridge pier at Sweetwater. Some ornithologists therefore conclude the Anhinga's spread-wing display actually has a thermoregulatory function that warms them when wet and cools them when hot. (Birds such as vulture, which do not swim and are not related to Anhingas, exhibit a similar behavior--as do cormorants, the Anhinga's first cousins.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We saw Anhingas at Sweetwater spread their wings from just about any perch, from the bridge pier and tree snags to the open grass of an earthen dike (above). Female and young male Anhingas are brownish with indistinct wing markings, while males are black with silvery-white covert feathers. Thus, the bird in the photo above is apparently an immature male that hatched in 2019. (Jim Shuman referred to the Anhinga's wing markings as "piano keys"; of course, the colors are reversed, with sharps and flats being white instead of black.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Anhingas were common during our visit to Sweetwater, but also in evidence were numerous species of long-legged wading birds--many of which were white and stood out brilliantly against blue water and green vegetation. The largest of these was Great Egret (above), differentiated from other white members of the Ardeidae by its black legs and bright yellow-orange bill. This species is primarily a stalker that goes after its prey in slow-motion, often freezing in an odd posture before striking out with that rapacious bill.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center By comparison, the smaller Snowy Egret (above) has a black bill and black legs, with conspicuous yellow feet. It shakes its brightly colored toes in shallow water, startling potential prey from hiding places in the substrate. The plumes--aigrettes--of this species were widely sought by milliners--so much so that snowies nearly became extinct in the early 1900s. The National Audubon Society adopted Snowy Egret as its emblem and did much to turn public attitudes about bird conservation.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The orange-billed Cattle Egret is nearly a dwarf of the Great Egret, except its neck is much shorter and it often has rusty feathers on its crest and nape. Unlike all the other waders on this page, the Cattle Egret is a non-native that apparently made its way from Africa to the Western Hemisphere on its own during the middle of the last century. It now breeds throughout the southern U.S. and ranges as far as southern Canada during post-breeding dispersal. Curiously, it seems NOT to have displaced any native species, preferring to feed within grassy areas rather than in wetlands like other waders.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When it comes to white waders having heavy bills, the Wood Stork (above) takes the prize. Its stout mandibles are surprisingly sensitive; the stork uses them to feel for submerged items and snaps the bill shut when suitable prey is encountered. Like the Snowy Egret, Wood Storks also use their feet--this time with pink toes--to stir up aquatic creatures. This species' naked head is possibly an adaptation for probing around in muddy water filled with vegetation that might otherwise become entangled in its cranial feathers.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another white wader that probes around for prey is the White Ibis, whose slender decurved bill is just the tool for grasping squirmy crayfish (see photo above) from a pond bottom. This species is relatively common very close to the coast from Virginia to Central America; its densest populations are likely in Florida and the Caribbean.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Some ornithologists speculate that being white in a hot, sun-drenched habitat helps keep pale-colored waders from absorbing too much solar heat, but Sweetwater also had its share of long-legged birds that bore DARK plumage. At left above is a Little Blue Heron, with a Glossy Ibis at right. Note also the male and female Blue-winged Teal between the waders; this was the most common duck species we observed during our day trip to the wetlands.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Here's a closer view (above) of an adult Little Blue Heron, whose blue wings and body, purplish neck, and black-tipped blue bill are diagnostic. (Incidentally, immature little blues happen to be WHITE, but their bill pattern still gives them away!) This species is sometimes confused with Tricolored (Louisiana) Heron--of which we saw only a few at Sweetwater--but the latter has a white belly and throat and a redder neck.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One other dark wader we observed was Glossy Ibis, whose wing plumage was iridescent when the light was at the right angle (above); otherwise the species appears dark brown or almost black. Note the maroon neck and head and the slender, decurved bill. Thin white lines above and below the eye sometimes lead observers to misidentify this bird as a much-less-common White-faced Ibis, but in that species the white is more extensive and the legs are reddish. (In the U.S., White-faced Ibis is a more westerly species.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The largest of Sweetwater's wading birds was also dark: Great Blue Heron, standing 4.5' tall and with a wingspan of up to 6.5'. (Great Egrets are about 3.5' tall with 5.5' wingspans.) This species has a huge distribution, occurring virtually everywhere in the U.S. except Arizona deserts and high elevations in the Rockies; they even breed across southern Canada east of British Columbia. It's worth noting from the photo above that Great Blue Herons--like all their relatives among herons and egrets--fly with legs extended and necks pulled back in serpentine formation.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center This wading bird flight configuration is worth remembering because folks often refer to members of the heron/egret family (Ardeidae) as "cranes" (Gruidae), which they are not. Among other differences, cranes fly with legs AND necks outstretched in a "flying cross"; we looked hard for Sandhill Cranes wading in the wetlands at Sweetwater but only got the above glimpse of them passing overhead. However, we did hear Sandhill Cranes giving their loud trumpet-like call, to our ears one of the most primeval sounds in all of nature.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Even though we were in subtropical Florida, not much was flowering in mid-December at Sweetwater. One noticeable yellow bloom (above) was Peruvian Primrose-Willow, Ludwigia peruviana, a non-native that blooms year-round in Florida. Imported from South America, it grows to 12 feet in height and can form dense shoreline and floating mats that crowd out other vegetation and clog waterways.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We saw plenty of wading birds at Sweetwater Wetlands Park, the most abundant species undoubtedly being American Coot; these occurred in large numbers on nearly every expanse of open water. The photo above shows only about a quarter of the coots that were in this particular raft.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Coots, with rails, are in the Rallidae, whose members are often identifiable by an upper mandible that extends onto the bird's forehead. In American Coots, the chicken-like mandibles are bright white and are sometimes used to bulldoze through duckweed, as above.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Closely related to the all-black coot is the Common Gallinule (above), once called Moorhen or Marsh Hen. In this species the body is two-tone gray/black and the yellow-tipped bill is otherwise orange--including the shield-like extension on the forehead. Note also the white striping on its side.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The most colorful local member of the Rallidae is Purple Gallinule (above), whose iridescent rainbow hues are breathtaking in good light. (To quote the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology: "Purple Gallinules combine cherry red, sky blue, moss green, aquamarine, indigo, violet, and school-bus yellow--a color palette that blends surprisingly well with tropical and subtropical wetlands.") What doesn't show in our photos of coots and gallinules is extremely long toes with which they are able to walk on floating vegetation; they also use their elongated digits to flip over lily pads in search of prey. All three species are essentially omnivorous, eating plant matter, snails, insects, and other invertebrates small enough to swallow.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although Muskrats, North American River Otters, and various snakes and turtles occur at Sweetwater, the only non-avian vertebrates we observed during our outing to this splendid facility were American Alligators. We saw one giant bull gator that was probably in the 12-foot range--we didn't get close enough to measure!--but relative youngsters like the six-footer above were more common. Alligators are apex predators at Sweetwater; they eat whatever they want, including any ducks, wading birds, coots, and Anhingas they can grab with multiple teeth and trap-like jaws. Let the birdwatcher beware! Thanks to Jim Shuman for a great day in the field in Florida, and to the powers-that-be in Gainesville for a conservation vision that created Sweetwater Wetlands Park and protects the flora and fauna therein. It's not coincidental that when we take care of natural resources and wildlife, we're also taking care of people who likewise depend on sweet, potable water--the essence of life itself.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center ADDENDUM: When we went to visit with Jim Shuman in Florida, we were invited to participate in the Marion County Christmas Bird Count and were assigned the sector of On Top Of The World that included Jim's residence. Birds were surprisingly scarce, with Palm Warblers and crows outnumbering all other species. Our five-person group in two parties tallied 44 species, with our personal "Bird of the Day" being a very brightly colored Yellow-throated Warbler. We managed to get a photo of a Red-shouldered Hawk (RSHA, above) perched on a power pole at the community recycling facility. To our eyes, this bird seemed quite small and pale--especially by comparison to RSHA that are regulars at Hilton Pond Center.

Checks also can be sent to Hilton Pond Center at: All contributions are tax-deductible on your Don't forget to scroll down for Nature Notes & Photos, |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

|

suffered from debilitating effects of non-alcoholic liver disease, spending the last week of the month in hospice at home in Ocala FL. She passed away on 30 November with Jim and her three children at her bedside. I met Jim in 1964 when I was a South Carolina delegate and he a counselor at West Virginia's National Youth Science Camp, and our relationship has deepened immensely through the years. In May 1996 I was privileged to attend when Laurie and Jim were married in the high school auditorium at Gouverneur NY; Laurie was an elementary school principal at the time and her students participated in the ceremony! Susan B. Hilton and I came to know and love Laurie and shared visits with her and Jim at their home and ours.

suffered from debilitating effects of non-alcoholic liver disease, spending the last week of the month in hospice at home in Ocala FL. She passed away on 30 November with Jim and her three children at her bedside. I met Jim in 1964 when I was a South Carolina delegate and he a counselor at West Virginia's National Youth Science Camp, and our relationship has deepened immensely through the years. In May 1996 I was privileged to attend when Laurie and Jim were married in the high school auditorium at Gouverneur NY; Laurie was an elementary school principal at the time and her students participated in the ceremony! Susan B. Hilton and I came to know and love Laurie and shared visits with her and Jim at their home and ours. sharing sadness, reliving old times, and looking to the future. Jim, a naturalist and retired college education professor, was actually the person who got me into birding in the mid-1970s, so it isn't surprising he and I would be toting binoculars and going out to explore local habitats in and around Ocala. One morning during the eight-day visit we drove to the outskirts of nearby Gainesville, where visionaries have begun reclaiming wetlands to protect water resources for the metropolitan area. The following photo essay, lovingly dedicated to Laurie's memory, highlights some of the flora and fauna Jim and I saw on our 19 December 2019 day trip to Sweetwater Wetlands Park.

sharing sadness, reliving old times, and looking to the future. Jim, a naturalist and retired college education professor, was actually the person who got me into birding in the mid-1970s, so it isn't surprising he and I would be toting binoculars and going out to explore local habitats in and around Ocala. One morning during the eight-day visit we drove to the outskirts of nearby Gainesville, where visionaries have begun reclaiming wetlands to protect water resources for the metropolitan area. The following photo essay, lovingly dedicated to Laurie's memory, highlights some of the flora and fauna Jim and I saw on our 19 December 2019 day trip to Sweetwater Wetlands Park.

Oct 15 to Mar 15:

Oct 15 to Mar 15: