- Established 1982 -HOME: www.hiltonpond.org

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

| WHAT? ANOTHER NEW LATE WINTER WILDFLOWER? Last week at Hilton Pond Center we were startled to find a late winter wildflower new to the property; it was especially astounding because it was growing just a few feet from our office window at the old farmhouse AND had produced a yellow bloom--something that can't happen until the plant is at least two years old (indicating it must have been present in at least one past year). The species in question was Trout Lily, Erythronium americanum, common across the Carolina Piedmont but not expected to appear seemingly "out of nowhere" at the Center.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Cheered by our discovery of the Trout Lily, this week we were taking advantage of balmy but misty weather on the first true day of spring (19 March), when what to our wondering eyes should appear but ANOTHER wildflower we had not yet documented locally. This one--white with lacy tripartite leaves (above)--was distinctive and easily recognized despite our surprise. It was Dutchman's Breeches, Dicentra cucullaria, a native species found in rich woods across North America east of the Rockies. (There is a disjunct population in the Pacific Northwest.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Dutchman's Breeches are named for their supposed resemblance to the traditional baggy pantaloons once worn by Nederlander men in the province of Voldendam (below right)-- Like many late winter/early spring ephemeral wildflowers, Dutchman's Breeches blooms before trees leaf out and block rays of all-important sunlight from reaching the forest floor. One other thing: The upside-down trousers on Dutchman's Breeches have a "yellow waistband" where the petals open. As with last week's Trout Lily, we're perplexed over how Dutchman's Breeches suddenly appeared at Hilton Pond Center, this time beside one of the water features we maintain to quench the thirst of birds and other wildlife. Perplexed, yes, but also pleased to be able to add another native wildflower to the Center's always-growing checklist of herbaceous plants. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center MORE LATE WINTER FLORA Since we were set up with camera, tripod, and macro lens to photograph that newly discovered Dutchman's Breeches, we decided to wander around our 11 acres to see what else might be blooming. We didn’t find any other new species, but did encounter several old floral friends, some native, some not. Below we include photos of a few of them, with a comment or two for each.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Perhaps the tiniest flower we found was Slender Speedwell, Veronica filiformis, a quarter-inch blossom of the pale blue shade known to Chinese artists as "the sky after rain." Also called Creeping Speedwell, this species often forms dense mats in late winter and early spring and then disappears. It was introduced from northern Turkey and is the bane of lawn enthusiasts who try to eradicate it with specialized herbicides. Our advice: Forget your environmentally disastrous grass lawn, let Slender Speedwell grow, and enjoy these delicate, eye-pleasing flowers while you can. In the Plantain Family (Plantaginaceae), speedwell is visited by native bees and Flower Flies but often self-fertilizes; it propagates most frequently by creeping stems.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another foreign plant that often invades lawns is Indian or Mock Strawberry, Duchesnea indica (aka Potentilla indica). As the species name suggests, it came from India and has become naturalized across much of the U.S., including at Hilton Pond Center. The leaves are similar to those of commercially grown strawberry (Fragaria spp.), but its edible red fruits are small and essentially tasteless. Native wild strawberries and commercial varieties have white flowers, while those of Indian Strawberry are yellow, as shown. The five petals and overall structure put all strawberries in the Rose Family (Roscaeae). You can see the similarity above to the general form of a simple, wild rose.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center On a gnarled old tree at the edge of a small meadow at the Center we found another five-petaled flower. This one was white, but it also was in the Rose Family. The tree? A Common Pear, Pyrus communis, undoubtedly planted at least 60 years ago when a former farmer tossed a half-eaten core while plowing his field. Pears--like apples (which are also in the Rose Family)--are non-native, having been brought over by early settlers from eastern Europe. We have several Common Pear trees on the property, and each year they produce small fruits too hard for our teeth but just the thing for White-tailed Deer and other mammals seeking a sweet snack. These pears don't appear to be spreading--unlike the non-native Bradford Pear, P. calleryana, a much-overused landscape plant that is fast becoming an invasive weed tree across much of the South.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Just into the woods on the other end of the meadow where we photographed Common Pear blossoms we found yet another five-petaled white blossom on a tall shrub. This flower was more delicate than that of the pear and had orange-tipped stamens and a green pistil that were much longer. Yes, it was yet another member of the Rose Family but this time a native--one of the wild plums, Prunus sp. Several kinds of native plums grow in the Carolinas, as does the domestic but imported P. persica--the Common Peach. Thus, identifying native Prunus to species can be a challenge--especially when we learn cherries are also in this genus! The task is somewhat easier if one can examine leaf, flower, fruit, and seed, but these never occur all at the same time. Nonetheless, using a hand lens and a well-worn copy of Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas by Radford, Ahles & Bell, we toiled through the identification key, meanwhile noting that our plum tree had rough exfoliating bark and formidable, two-inch-long, downward-pointing spines (ouch!). Based mainly on leaf characteristics, we eventually concluded our resident species is most likely P. americana, American (Wild) Plum. We'll be watching for fruit in a few weeks for further verification--assuming pollination occurs and we can keep the deer away.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One other white flower caught our eye and our camera lens this week--one that was a mere quarter-inch in diameter. We knew in general what it was--one of the Chickweeds, Stellaria--but since there are as many as 120 species worldwide (many with cosmopolitan distribution), identification could be a magnitude harder than for our relatively small assortment of Carolina plum species. Thankfully, many chickweeds don't even occur in North America; better yet, the aforementioned botany manual by Radford et al. lists only five Carolina chickweeds, so we gave it a shot.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center First, a word of caution. In the chickweed flower (enlarged above), if you count the number of sepals--the green pointed structures that once protected the developing flower bud--you should come up with "five." But if you count the petals you likely will arrive at "ten" . . . and that would be wrong. Chickweeds have only five petals, with each one split almost all the way to the base. (This is easily seen in the petal at lower right in the photo.) There aren't many flowers with ten petals. With that interesting factoid out of the way, we ruled out the Carolina chickweed species one-by-one because of habitat, size, or time of bloom, and finally concluded we had photographed S. media, Common Chickweed, native to Eurasia and found worldwide. It's in the Carnation Family (Caryophyllaceae) and can be eaten as a leafy vegetable; ground-feeding birds consume the seeds.

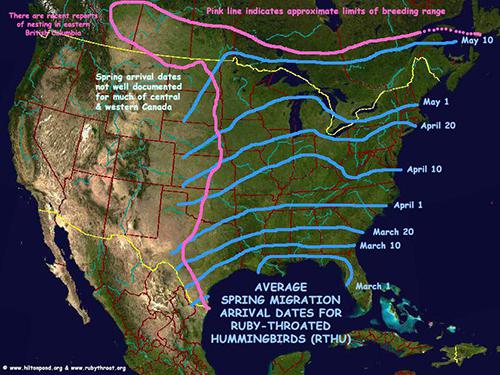

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our final late winter wildflower at Hilton Pond Center was one that should be known to all residents of South Carolina, where it is the state flower: Yellow Jessamine, Gelsemium sempervirens. One of our pet peeves is when folks call this plant "jasmine." Even plant nurseries do it, but jasmine is something else entirely--a group of Olive Family (Oleaceae) shrubs and vines from Eurasia and Oceania. Yellow Jessamine is a down-home native twining vine in the Gelsemiaceae (but was formerly in the Loganiaceae). Jessamine is a hardy, sun-loving vine whose canary-colored flowers brighten roadsides in March and April across the Carolina Piedmont and Coastal Plain. There, its trumpet-shaped blossoms attract native Bumblebees and butterflies. Alas, the native plant's nectar is toxic to non-native Honeybees, so beekeepers whack any vine they find within flying distance of their hives. Consumed in quantity, the foliage also can be fatal to livestock. (Note the pointed, purplish-green leaves that usually are not deciduous.) Call it Yellow Jessamine or Carolina Jessamine, just don't call it "jasmine." Why, that would be like calling South Carolina the Palm State instead of the Palmetto State! Late winter wildflowers are about done at Hilton Pond Center. Let the spring bloom begin! All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center RUBY-THROATS ARE COMING! Although Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project has an international presence, much of our hummer research occurs at Hilton Pond Center near York SC--smack in the middle of the Carolina Piedmont. The earliest spring migrant Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (RTHU) have occurred here on 26 March in several different years, so our standard suggestion for folks in this general region is to hang one feeder by 17 March--St. Patrick's Day. Don't fill the feeder all the way, and keep an eye out for your first hummer. Observers north of us will see their first RTHU later in the season, so we're providing our spring migration map (below) for your reference. Just have that feeder up about ten days before the expected arrival date, and Happy Hummingbird Watching! (Click on the map to enlarge it.) All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center CLICK ON IMAGE ABOVE TO OPEN A LARGER MAP IN A NEW WINDOW

Checks also can be sent to Hilton Pond Center at: All contributions are tax-deductible on your Don't forget to scroll down for Nature Notes & Photos, |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

|

even though those dapper gentlemen's pants were dark and never spotless white like our new wildflower. Dutchman's Breeches is called "Little Blue Staggers" by ranchers because cattle that graze on its toxic, narcotic-laden foliage may stagger around drunkenly. This isn't a surprise when we realize Dutchman's Breeches is in the Papaveraceae, the Poppy Family.

even though those dapper gentlemen's pants were dark and never spotless white like our new wildflower. Dutchman's Breeches is called "Little Blue Staggers" by ranchers because cattle that graze on its toxic, narcotic-laden foliage may stagger around drunkenly. This isn't a surprise when we realize Dutchman's Breeches is in the Papaveraceae, the Poppy Family.  At this time of year the species is an important nectar source for Bumblebees, but the flower--with its unusual configuration of two white outer petals and two yellowish inner petals--requires pollination by bees with long tongues. Like the Trout Lily we discovered last week at the

At this time of year the species is an important nectar source for Bumblebees, but the flower--with its unusual configuration of two white outer petals and two yellowish inner petals--requires pollination by bees with long tongues. Like the Trout Lily we discovered last week at the  Another closely-related species--Squirrel Corn,

Another closely-related species--Squirrel Corn,

Oct 15 to Mar 15:

Oct 15 to Mar 15: Please report your

Please report your