- Established 1982 -HOME: www.hiltonpond.org

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

A STRIKING BUTTERFLY, Although 11-acre Hilton Pond Center is almost completely vegetated, growth consists mainly of young trees and shrubs--and not many flowering herbs or forbs. Woody plants are also flowering plants, of course, but many make blossoms that seem less attractive to nectar-seeking butterflies, hence the Center's somewhat sparse assemblage of butterfly species. When we DO spot one of these scaly-winged creatures flitting about we run for the camera in hopes of capturing a few images and adding something new to the yard list. Such was the case on 18 September when a small but very colorful butterfly rested a bit on one of the mist nets we use to catch birds for banding.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Up close we realized this little individual--about an inch and a quarter long--was a species already on our Hilton Pond Lepidoptera Inventory. It was a Great Purple Hairstreak, Atlides halesus, so-named for purplish underwings and thin hair-like projections on its hindwings. (Look closely at our photo above for the little "tails," which are more visible in the image below.) This species is also called Great BLUE Hairstreak because the dorsal side of its wings is iridescent sky blue. (We couldn't get the butterfly to spread-wing for a top view, but the underside was still spectacular enough to share herein.) None of our macro photos of the hairstreak on the net were usable—the wind was blowing things around a good bit—so we were pleased when the butterfly fluttered over and settled down for a “knuckle perch.” There it unrolled its proboscis and gently probed our skin. Butterflies normally get dissolved minerals from “puddling” on moist soil, but human perspiration seemed to have salt enough to meet that need. (Female butterflies do puddle in some species, but most "puddlers" are males that pass sodium to their mates via the sperm-containing spermatophore. Sodium, in turn, appears to enhance egg viability.) "On-the-hand" our hairstreak constantly slid its hindwings up and down, alternately exposing and then hiding a brilliant metallic blue spot on the underside of each forewing (see photo above). As if this weren't enough color, the butterfly also showed / covered / showed a yellow-orange abdomen (below) that was quite plump. Note also those red splotches at the wing-bases, plus white spots on the butterfly’s thorax--all of which make the butterfly's body look more like some sort of wasp.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Great Purple Hairstreak is a southern butterfly, found from North Carolina south and west all the way to California. Some authors refer to it as a Neotropical species since it occurs in appropriate habitats throughout Mexico and Central America as well as in “subtropical” parts of the U.S. Interestingly, here at Hilton Pond hairstreak larvae dine exclusively on the thick, tough leaves of Eastern Mistletoe, Phoradendron leucarpum--colonies of which grow on the big Shagbark Hickory tree behind the Center’s old farmhouse. This probably explains why we’ve never actually seen a hairstreak caterpillar: Mistletoe is “hemiparasitic” on the highest hickory limbs at least 60 feet in the air! Hemiparasitism, however, is a topic for another time. For now, let’s just enjoy these photos of the Great Purple Hairstreak!

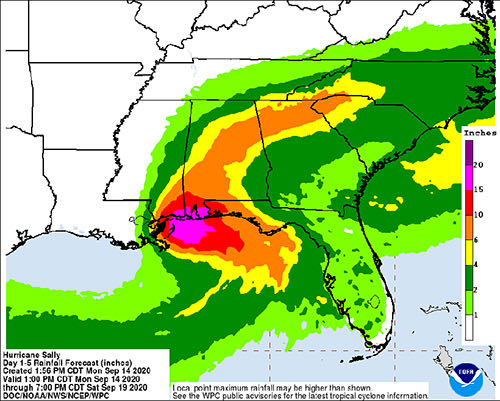

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center LATE SEPTEMBER'S BIRDS Days with little wind, mild temperatures, and overcast skies are best for deploying mist nets to capture birds for banding. Such was the case on 18 September at Hilton Pond Center, with temps in the low 70s, occasional slight breezes, and high cloud cover, all supplemented with haze caused by drifting smoke from California fires. It helps when there have been rainy events previously--bad weather causes migratory birds to "stack up" as they wait for more favorable flying conditions--and we did have an 1.88" gully washer related to Hurricane Sally on the 17th through the wee hours on the 18th. (The map above shows anticipated rainfall from Sally; we were unable to find a map showing actual final precipitation, but it was very similar to predictions. )

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As anticipated, the 18th turned out to be the first day for a "real" fall migration at the Center, with 20 individuals of 10 species crossing the banding table:

Of these the AMGO, HOFI, and BRTH were more than likely summer residents--as may have been the RTHU--but the rest almost certainly were pass-throughs from up north. It was unusual for us to get three Northern Parulas in one day--we've just banded 86 of them in 39 years at the Center--but historically it hasn’t been uncommon in autumn to capture several Swainson's Thrushes (SWTH) here within a few hours of each other.

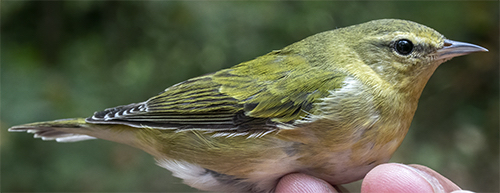

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center All four SWTH (above) were immatures that fledged somewhere far from Hilton Pond; these are true long-distance migrants that breed across almost all of Canada and in New England and around the Great Lakes. After leaving us with a band on its leg, each successful SWTH migrant will end up in southern Mexico or as far away as northwestern South America. Our photo above of the Swainson's Thrush shows its important field marks: Buffy face and breast, complete eye ring, prominent ventral streaking, and a uniformly olive-brown dorsum from head to tail.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Throughout September's latter half, migration banding continued at a steady pace, with most days yielding about 15 individuals--as shown below. After 20 birds captured on the 18th (see list in discussion above), the 19th yielded another 20. The biggest day was the 27th with 40 bandings--in part because of the sudden appearance of 13 American Goldfinches in our nets. Ruby-throated Hummingbird (RTHU, hatch-year male, above) numbers--in parentheses on the list below--were pretty consistent until near month's end. (For a complete tally by species of birds banded 16-30 September, scroll down to the bottom of this page.)

Below is an annotated portfolio of just some of the 32 species caught, banded, and released during the period at Hilton Pond Center.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center All four of the expected resident or early fall migrant "spot-breasted thrushes" hit our nets in late September: Swainson's Thrush (photo above, ten banded), and one each of Gray-cheeked Thrush (GCTH, below), Veery, and Wood Thrush. The latter is the only species that breeds at Hilton Pond Center, with the rest occurring just during migration. Missing from our spot-breasted tally were Hermit Thrushes, but we never expect them until about mid-October. (NOTE: A smaller version of the gray-cheeked known as Bicknell's Thrush is now recognized as a sixth species; it is relatively rare and has never been detected during migration at the Center.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center All six spot-breasted thrushes are superficially similar, but Gray-cheeked Thrushes (above) lack the facial buffiness of a Swainson's, are uniformly grayish-brown on the dorsum from head to tail, and have an indistinct eye ring. Based on measurements, our localy banded GCTH tend to be a tad larger than all spot-breasteds except Wood Thrush. A total of 131 Gray-cheeked Thrushes banded since 1982 make them much less common than Swainson's Thrushes with 563.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Other than our Ruby-throated Hummingbird target species--for which we banded 46 individuals--the most common birds in our nets during the latter half of September 2020 were American Redstarts with a surprising 24 captured. Only three of this fall's AMRE were black-and-orange adult males; the rest were comparatively drab females or immature males like the one in our photo above. Note the yellow wing spot and prominent yellow at the tail feather bases that make this a hard warbler to MIS-identify. With 550 individuals banded since 1982, American Restarts are one of three warbler species in Hilton Pond's "400 Bandings Club"; the others are Yellow-rumped Warbler (a whopping 2,332) and Magnolia Warbler (433).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Fall migration typically brings a variety of Wood Warblers to Hilton Pond, but from year to year we never know which species to expect. (Of the 38 likely "eastern warblers," through the years we've banded 35, missing only Kirtland's, Cerulean, and Mourning.) Although--as noted above--American Redstarts were the most abundant parulid in late September, we were a bit surprised the next most common were Cape May Warblers (CMWA) with 15 banded. CMWA are not abundant at the Center--we've banded 137 in 39 years--although we did capture a record-setting 45 in the autumn of 1991. (Our Cape May Warbler average is just four per year, with 88% of bandings occurring in fall migration.) CMWA are one of those warblers with a yellow-rump (see above), although this mark is not as prominent as in the eponymous Yellow-rumped (Myrtle) Warbler. Rather nondescript immature Cape May Warblers like the one in our photo are most easily identified in fall by the yellow "ear."

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As noted above, our third most common parulid at Hilton Pond Center has been Magnolia Warbler (MAWA), but this year we only handled three during the last half of September. (We expect more to pass through in early October.) Ask most birders to explain how they identify immature MAWA in autumn and they'll likely say they look for tail spots that form a wide band of white halfway down the tail. But for us, the definitive field mark for young Magnolia Warblers is a gray necklace (see above) between the yellow of the throat and chest. On most individuals the necklace is quite noticeable even from a distance. Incidentally, 87% of our MAWA have been captured during fall migration, meaning in spring we seldom get to see adult males in full breeding plumage.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Tennessee Warblers (TEWA, immature above) also started showing up at the Center in late September, for a total of 12 bandings for the month. We often hear from folks they have trouble identifying nondescript greenish TEWA in autumn, but for us they're one of the easiest warblers to distinguish. (It's probably helpful we band more TEWA on our Central America study sites than any other bird--including our sought-after Ruby-throated Hummingbirds!) The key for us in recognizing Tennessee Warblers--which breed in northern Canada nowhere near Tennessee--is to observe bill shape; the species has a very finely pointed bill unlike that of other Wood Warblers. In fall, also look for a thin dark line through the eye and a LACK of other typical warbler field marks: No wing bars, no tail spots, no other noticeable characters. (This is almost like saying rule out every other warbler, and you've got a TEWA!)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Most yellowish birds that pass through Hilton Pond Center during late September migration are Wood Warblers, but a few are not. Although the one in the photo above resembles a warbler, a close look at its bill tells you otherwise. The mandibles are heavy, the top one is decurved, and right at the tip is a little notch-and-hook that helps this species make short work of caterpillars and adult insects that comprise most of its diet. It's a Yellow-throated Vireo (YTVI), a member of a family (Vireonidae) once thought to be related to warblers but actually is closer to corvids (crows and jays) and shrikes. Nearly all vireos are monomorphic, with both sexes appearing similar. Yellow-throated Vireos are quite scarce at the Center; this week's bird was the first since 2007 and our 40th in 39 years.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center With 32 banded species to choose from during the last of September it's hard to choose which others to highlight, but we'll close out this installment with three we found worthy of particular mention. Although the first is a bird we see often away from Hilton Pond Center--and almost daily along the roadside in front of the property--we capture and band it with relative infrequency. We speak here of Northern Mockingbird (NOMO, dark-eyed immature, above), of which we've banded 181 in 39 years. NOMO almost certainly breed somewhere on our 11 acres, but it may just be things aren't shrubby enough for the species to be abundant. (Although we've never found a mockingbird nest here, we've caught recent fledglings and females with active brood patches.) We see many more Northern Mockingbirds in winter, perhaps because they're less territorial then or because some come south to warmer climes when cold weather hits up north. (By the way, if you've ever wondered why our local species is called Northern Mockingbird, it's because there is a very similar Tropical Mockingbird whose Central and South American range does not overlap.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The biggest bird we caught in late September was also one of the most distinctive: Yellow-billed Cuckoo (YBCU, above), with its slouchy posture, rusty wings, long tail, fleshy yellow eye ring, and habit of eating fuzzy caterpillars that many bird species ignore. Since 1982 we've banded a mere 56 YBCU, but even they outnumber the far less-common Black-billed Cuckoo of which we've caught just two. Both cuckoos--identifiable, of course, by lower mandibles of differing colors--are becoming increasingly rare as they fall victim to habitat loss on the North American breeding grounds and in Neotropical forests in which they spend colder months of the year. Since they are primarily insectivores, cuckoos are also hit by abuse and overuse of insecticides on both ends of their migratory path. (In winter, cuckoos may alter their diet a bit, also dining on fruit and seeds.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our last bird of note for late September 2020 looks pretty much the same in full color (above) as in its gray-scale image (below); after all, a female Hairy Woodpecker (HAWO) is basically just that: Black and white. A male Hairy Woodpecker would have a dash of red color on its nape, while young males bear a red crown that eventually disappears. In addition, adult HAWO of either sex have an iris that is deep plum red, so the female isn’t fully devoid of coloration. HAWO are genuinely scarce at the Center; the one banded this week was only our 29th during almost four decades. Compare this to the Hairy Woodpecker's smaller black-and-white cousin--Downy Woodpecker--of which we’ve banded 251. Generally, HAWO prefer dense forests with tall hardwoods, while DOWO are more likely in smaller woodlots with younger trees like those around Hilton Pond.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center All in all, our 32 species and 183 individuals banded during the latter fortnight of September made it an active period filled with bird diversity. We can’t wait to see what comes during migration in the historically productive first half of October at Hilton Pond Center. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Image post-processing via DeNoise AI, Sharpen AI, and other Topaz Lab tools

Checks also can be sent to Hilton Pond Center at: All contributions are tax-deductible on your Don't forget to scroll down for Nature Notes & Photos, |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Dr. Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

|

Please report your

Please report your