- Established 1982 -HOME: www.hiltonpond.org

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

FIRST SOUTH CAROLINA RECORD FOR As home since 1984 to Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project, Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History in York SC focuses in part on studying Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, Archilochus colubris (RTHU, immature male, below). Using mist nets and humane live-traps baited with sugar water, through 21 September 2021 we have captured, banded, measured, and released 6,889 RTHU at the Center; many of these have returned during one to seven subsequent summers.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our discoveries about ruby-throat sex ratios, longevity, survivorship, site fidelity, foraging behavior, and population dynamics have added significantly to a scientific understanding of RTHU that is useful in conservation efforts. After 38 years ours is one of the world's longest-running hummingbird projects, but we're always learning something new--as happened this week when we captured a different hummingbird species never reported from South Carolina! Sound exciting? Here's the story: On the morning of 20 September we arose shortly after dawn and deployed several mist nets as part of our general bird banding program. Traps containing hummingbird feeders mostly catch hummingbirds, but nets are non-selective; thus, they're just as likely to catch fall migrant warblers or resident Carolina Wrens as our target species of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. In other words, we never know what we might encounter on our regular net checks.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center During the 9 a.m. check on the 20th we noticed a hummingbird in the top shelf of a net near several sugar water feeders directly behind the Center's old farmhouse. When we extracted the hummer we saw it was slightly larger than a typical female RTHU; in addition we immediately noticed the wing (above) was rather long and that the #10 (outermost) primary feather was straight and with a thin vane on the lead edge. This was quite different from the configuration of a ruby-throated female's wider, slightly curved #10.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Still thinking this was a female hummingbird of some sort we looked at the gorget and were surprised to see three metallic feathers--one red, one green, and one red-and-green. In RTHU, only males have iridescent red feathers, so our suspicion was growing.

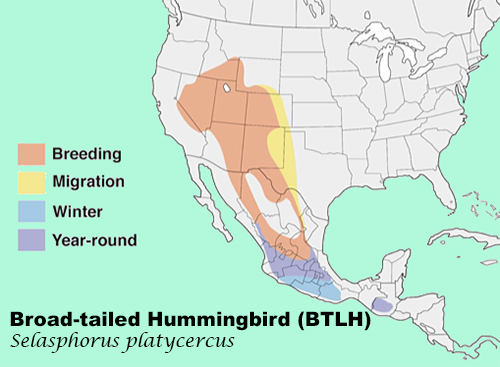

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our attention then went to the bird's tail feathers (aka rectrices), which had rufous bases. This absolutely ruled out Ruby-throated Hummingbird and led us to suspect one of the western vagrant Selasphorus hummingbirds that--with increasing regularity over the past three decades or so--have been showing up in winter in the eastern U.S. These include Rufous Hummingbird (S. rufus, which now occurs every year somewhere in the Carolinas); Allen's Hummingbird (S. sasin, which strongly resembles S. rufus but is much less common); Calliope Hummingbird (S. calliope, a smaller species that appears rarely in the East); and Broad-tailed Hummingbird (S. platycercus). We banded two vagrant Rufous Hummingbirds at Hilton Pond Center in November 2001 and September 2002, but the new capture’s long wings, narrow outer primary feathers, and fully rounded rectrices suggested a different Selasphorus species. When encountering a Selasphorus hummingbird one definitive way to determine species is through measurements. We took some in short order, using criteria described in Peter Pyle's Identification Guide to North American Birds. The bird's weight was 3.50g--about the same as a female RTHU--so this measure was not diagnostic. However, compared to all four Selasphorus species, our hummer's measurements of a 51.1mm wing chord, 31.0mm tail length, and 20.1mm culmen (exposed bill length) all indicated the bird in hand must be a Broad-tailed Hummingbird (BTLH), a species that breeds out west in the Rocky Mountains but has NEVER been reported from South Carolina! Pretty exciting, no?

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Now that we knew the species, to verify the bird's gender we needed to age the bird, which we accomplished using a hand lens to examine its upper mandible (above). In young hummingbirds, the bill shows many tiny corrugations or etchings that fill in and smooth out as the bird ages. Our hummer had a smooth bill with very few corrugations near the base, indicating it was an adult that had to have hatched out before the current calendar year. So if this was an adult bird, it had to be a female--despite its metallic gorget feathers--because adult male Broad-tailed Hummingbirds (below) look a lot like adult male Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, complete with full red gorgets.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Despite its superficial similarity to an adult male RTHU, however, the adult male Broad-tailed Hummingbird (above) has a gorget that's a bit rosier than ruby, has those long wings, is a tad larger, and has rufous in the rectrices. In addition, an adult male ruby-throat has a forked tail, while the broad-tailed's name says a lot about its tail configuration. (NOTE: The outermost #10 primary in an adult male BTLH has a flipped-up tip, an in-hand characteristic that would also differentiate it from an adult male ruby-throat.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In dorsal view (above) our adult female Broad-tailed Hummingbird looked very much like an adult female ruby-throat, except the long wings again stood out. Notice there is no brown edging to the back feathers; these would be another sign of an immature hatch-year bird.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Ventrally (above) our bird looked even less RTHU-like, with rusty flanks, rufous in the tail, and those metallic gorget feathers. We should point out that just like female and immature ruby-throats, female and immature male Broad-tailed Hummingbirds have white tips on the outer three rectrices. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our final image (above) is a lateral view of the just-banded adult female Broad-tailed Hummingbird on 20 September. After taking the requisite photos needed to document a new state species, we inserted her bill into one of our sugar water feeders and watched as she drank her fill. Upon release she flew straight up through the trees and out of sight across Hilton Pond. We have not seen her since, either at the feeders or in a mist net. This early in the season we suspect this western visitor will move on to some other locale.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We can only speculate what conditions or stimuli brought this western vagrant to South Carolina and Hilton Pond Center from its historical non-breeding area in Central Mexico (see map above). Perhaps recent hurricane activity in the Gulf of Mexico steered her in this direction, or maybe she's a pioneer that could expand the species' "normal" range. There is one photographic account for BTLH from North Carolina (December 2001) and several records from neighboring Georgia; eBird shows the species has been encountered numerous times along the central Gulf Coast after breeding season. We're just glad we were running mist nets "This Week at Hilton Pond" when a Selasphorus wanderer came to visit and become the first documented evidence for a Broad-tailed Hummingbird in South Carolina. Can you tell we're still excited? OTHER VAGRANT HUMMINGBIRD BANDINGS

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Operation RubyThroat is also credited with the first South Carolina record of a Buff-bellied Hummingbird (above) we banded on 1 December 2001 near Lexington, and with the first banding (second state record) of a Broad-billed Hummingbird (below) on 6 January 2008 near Rockville SC.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Other vagrant hummingbird species banded in South Carolina by Operation RubyThroat: Rufous Hummingbird (including two at Hilton Pond Center), Calliope Hummiongbird, and Black-chinned Hummingbird. One Rufous Hummingbird from the Center was encountered a year later in Ohio! NOTE: If you're east of the Mississippi and see a non-Ruby-throated Hummingbird at your feeders at any time, or if you observe a hummer of ANY species from 15 October to 15 March, please try to get a clear photo and contact us at RESEARCH. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center SEPTEMBER FUNDRAISER It is only through generosity of the public-at-large that we are able to continue Hilton Pond Center's non-profit initiatives in environmental education, conservation, and natural history research--including documenting South Carolina's first-ever Broad-tailed Hummingbird described above. A September fundraiser on behalf of the Center is still underway on Facebook and is getting close to its goal, so please contribute if you can before the month ends by clicking on: Bill Hilton Jr.'s 75th Birthday Fundraiser You can also donate at any time via PayPal and Network for Good (see links at the end of this page) or by sending a check to: Hilton Pond Center A RARE CAPTURE AND ANOTHER MILESTONE The 19th of September was a big day for banding at Hilton Pond Center. Among other things we caught a blackbird we seldom encounter. Now, this wasn’t just any blackbird and—in fact—it wasn’t even black. Granted, its wings were kind of blackish (with whitish wing bars), but its overall body color was yellow-orange. A blackbird that is orange, you ask? Yes, it might not be black, but it’s in the Blackbird Family (Icteridae), and happened to be a Baltimore Oriole (BAOR, below)--temporarily called “Northern Oriole” a few years ago until common sense took hold of avian taxonomists and they returned to its time-honored name.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center So why was this non-black blackbird so special? First, BAOR is a species that breeds uncommonly in northwestern South Carolina, so we see it only during migration—and then very rarely—probably because it's a tree-top dweller not likely to be captured in our mist nets at ground-level. (That said, notice the pokeberry stain at the base of the oriole's bill--a sure sign it came down from the canopy for a migration snack.) Today’s blackbird was also special because it was only our EIGHTH Baltimore Oriole banded at the Center in 40 years! Its plumage told us it was an immature bird, but since young BAOR of both sexes look pretty much alike it wasn’t until we measured a relatively short wing chord that we knew this bird was an immature female.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although it was nice to encounter a species we've handled so seldom, this Baltimore Oriole was also of interest because she was our 2,396th banded bird of 2021 at Hilton Pond; that means so far this year we’ve banded more birds than in any year since ‘way back in 1994. That’s quite a milestone and it’s only mid-September! (The next easily reached benchmark will be 2,447 birds banded, but we doubt we’ll get to our all-time high of 4,061 set in 1991.) This year’s numbers have been helped considerably by 988 Pine Siskins, 320 Purple Finches, and 319 American Goldfinches that combined for an unprecedented “winter finch irruption.” We've also handled 245 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds to date in what is right now our fifth-best year for that species at Hilton Pond. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center BIG BEETLE When The Goddess walked down to our office at Hilton Pond Center on the evening of 17 September and said “There was a big beetle flying around in the living room but it landed on the floor so I put a jar over it,” The Piedmont Naturalist knew for the millionth time he had married the right woman. Big living room beetles are a fairly common occurrence in our old farmhouse because the fireplace and chimney are open to the out-of-doors. Some spouses undoubtedly would want the smokestack capped and the fireplace boarded up—and certainly wouldn’t corral a large flying insect for the partner's perusal—but Susan Ballard Hilton has been strongly supportive of all our research, education, and conservation activities at the Center for all 40 years together here.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The subject of her latest encounter was indeed a stout black beetle (above) about an inch-and-a-half long with rows of rivet-like indentations on the hard elytra (forewings) and three-pronged projections on its anterior end. The latter give the insect its common appellation—Triceratops Beetle (scientific name: Phileurus truncatus). This one made a squeaky noise when we picked it up. These are among our most massive beetles, exceeded in size only by Hercules Beetles and Rhinoceros Beetles with which they share a subfamily (Dynastinae). At various times through the years these larger species have also come down the Center’s chimney and been welcomed just as warmly by The Goddess.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Unlike many insects that complete life cycles in 12 months or less, Triceratops Beetles may live several years as larvae and adults, often sequestered out of sight in old hardwood logs or stumps. The grub (above)--twice the size of an adult--chews and swallows decomposing wood fibers that are broken down into usable nutrients by cellulose-digesting microorganisms living in its gut; adults are predatory—mainly on larvae of big beetle cousins that occupy similar habitats. Since Triceratops Beetles are long-lived and easy to care for they are sometimes kept as pets. In fact, they and related species are so popular in Japan there are entire stores devoted to raising and selling these large harmless insects. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center BIRD BANDING SNAPSHOTS Here are a few photos of avian species banded during the third week in September 2021 at Hilton Pond Center:

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Most members of the North American Wood Warbler Family (Parulidae) are quite colorful, often with some amount of bright yellow in their plumage. Four notable exceptions, however, are mostly brown, including the two Waterthrushes (Northern and Louisiana) and the two birds shown here. We've banded all four this fall at Hilton Pond Center. The top bird, with four striking black head stripes and prominent bill, is Worm-eating Warbler (WEWA, above), one of those bird names that is misleading since it doesn’t often eat "worms." Like most warblers WEWA glean caterpillars and other invertebrates from shrub and tree foliage, occasionally taking prey items from leaf litter on the ground. The Center is right on the southeastern edge of this species' primary nesting range; even so, breeding has been confirmed for the South Carolina Coastal Plain. Worm-eating Warblers are quite uncommon locally, with only 53 banded since 1982.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Ovenbird (OVEN, above), so-named because it builds a covered ground nest in the style of old-fashioned brick ovens, has just two black head stripes with a rusty patch between. It, too, has a brown dorsum but the undersides are white with heavy dark streaking on the breast. (The species is sometimes confused with various spot-breasted thrushes, but none of them have such distinctive head markings.) Again, Hilton Pond Center sits at the southern edge of this warbler's main breeding range but in this case scarce nests have been found statewide. Unlike the leaf-gleaning Worm-eating Warbler, Ovenbirds are primarily ground feeders, plucking caterpillars, flies, and beetles and their larvae from the forest floor. They are among the few warblers that consume ants when they encounter a big colony. Much more common in migration than the Worm-eating Warbler, we've banded 236 Ovenbirds in 40 years at the Center.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although Summer Tanagers have produced young at Hilton Pond Center, Scarlet Tanagers (SCTA, immature female above) are yet another species that typically nests just to the north and west of us. (That said, there ARE scattered SCTA breeding records for South Carolina's northern Piedmont.) Both tanager species are sexually dimorphic as adults, with SUTA males being bright crimson and females yellow-green; young males resemble females but usually have bright yellow or orange undertail coverts. Scarlet Tanager males are, well, scarlet--but with black wings; females of any age are greenish-yellow with gray-green wings, as above. (Young male SCTA resemble females early on but by the time we see them here in fall migration they usually have one or more black feathers in their wings.) As expected, at the Center Summer Tanagers (211 banded since 1984) are about twice as common as Scarlet Tanagers (139); for both species 81% have been captured during fall migration.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although the locally uncommon Baltimore Oriole we banded this was a real treat (described in detail above), we were also pleased to capture an immature female Hairy Woodpecker (HAWA, photo just above). This black-and-white species--of which we've banded just 30 individuals since 1982 at Hilton Pond Center--looks like the smaller Downy Woodpecker (DOWO) on steroids. (DOWO are half the size of HAWO are are much more common locally with 266 banded.) In both these species adult males have a red patch on the nape, a field mark lacked by females. When the two species are at a feeder together they are easily distinguished; apart, look for a much longer bill on the hairy--more that half the length of the head, as above (the bill's less than half that in DOWO)--and for black spots on outer white tail feathers of the downy (these are typically unmarked in HAWO, as below). In our experience Downy Woodpeckers are much more aggressive than their larger relatives, often pecking our hands mercilessly when we try to hold them for photos. This week's Hairy Woodpecker was quite docile and posed without drawing blood.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Don't forget to scroll down for lists of all birds banded and recaptured during the week. HILTON POND SUNSETS "Never trust a person too lazy to get up for sunrise

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Sunset over Hilton Pond (above), 18 September 2021 Photoshop image post-processing for this page employs |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Dr. Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

|

Please report your spring, summer &

Please report your spring, summer &