- Established 1982 -HOME: www.hiltonpond.org

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

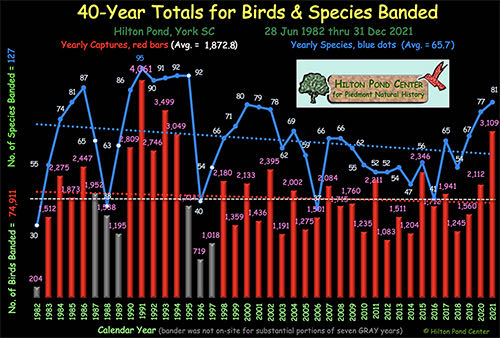

2021 BIRD BANDING SUMMARY: ••THUMBNAIL RESULTS•• At Hilton Pond Center we arbitrarily established 2,000 as a realistic round-number goal for how many birds we'd like to band each calendar year. We exceeded that goal for the 17th time in 2021 and finished with our third-most-productive year since 1982 with 3,109 bandings--well above our 40-year average of 1,873. (The all-time high was 4,061 in 1991.) We banded 81 species in 2021, our best tally since 1995 and tied for our 8th-highest-ever; the average number of species banded per year at the Center is 65.7. (The all-time high was 95, again in 1991.)

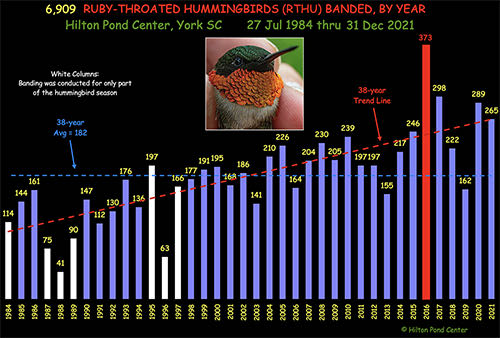

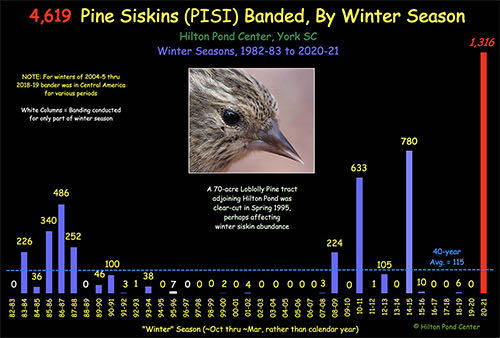

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our numbers were swelled this year by an unusually large and long irruption of Pine Siskins (above); we banded an unprecedented 988 of these Canadian breeders in early 2021 (with an amazing 1,316 during the entire winter of 2020-21). Other big numbers from the just-ended year came from six other species: 341 American Goldfinches and 320 Purple Finches—both migrants from up north (although a few goldfinches banded here in summer were apparent year-round residents); an unexpected 279 Yellow-rumped Warblers (all but seven of which appeared in late 2021); 265 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (somewhat fewer than last year's 289 but well ahead of our average of 182); 112 House Finches (likely non-migrants, with their second-worst year since the late 1990s); and 104 Northern Cardinals (whose local population has improved during the past few years). Just these seven species combined for 2,409 individuals, or 77% of the 2021 yearly total.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We added our 173rd new species to the Hilton Pond "Yard List" with a September capture of South Carolina's first state record Broad-tailed Hummingbird (her distinctive tail, above). This hummer was our 128th species banded at the Center since 1982. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center ••END-OF-YEAR THANKS•• Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project could not implement banding programs and other initiatives without the generosity of individuals who donate in support of our work in environmental education, conservation, and natural history research. We acknowledge these financial gifts individually throughout the year at the end of each installment of "This Week at Hilton Pond."

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In 2021 we were particularly grateful for contributions from these multiple-year "Top Tier Sustaining Donors": Marie Baumann, Ramona & Jim Edman, Lynn & Terral Jordan, Gail & Tom Walder, and Mary Kimberly & Gavin MacDonald (far right and far left in a 2019 photo above with Susan & Bill Hilton Jr.); all these are citizen science alumni of one or more Operation RubyThroat Neotropical hummingbird expeditions. Margaret & Robert Lloyd and John McCoy were also "Top Tier Donors" in 2021. Sincere thanks to them and to everyone else for such thoughtful generosity. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center ••BACKGROUND INFO & METHODS••

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We open our mist nets most days at Hilton Pond Center, but for bird welfare we don't deploy when it's too hot for us OR the birds (above 90 degrees or so) . . . or below 40 degrees . . or when it's windy . . or in the rain. Thus, weather limits our work, and climatic differences year-to-year at the Center have definite impact on banding results. Throughout most of 2021, rainfall and temperature were about average--although the last few months saw drought-like conditions that dropped the pond water level by nearly three feet by year's end. (The sunset photo below from early December shows the extent of exposed mud banks on the north end of the pond.)

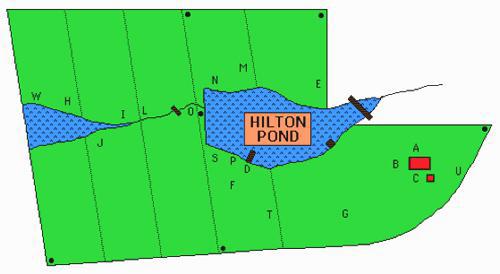

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Regardless of weather, we almost always run a few sunflower seed traps each day for songbirds (locations A, B & C around the old farmhouse on the Center's plat, above); late March through mid-October we also concentrate on trying to capture Ruby-throated Hummingbirds coming to sugar water traps dawn to dusk at those three locations.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We do not tally net- or trap-hours at Hilton Pond Center. (The photo above shows several styles of traps; a mist net in the background is still furled.) We find this accounting too complicated because of the way we have to operate--e.g., closing nets and traps periodically during the day to run errands, etc.--so we can't really compare actual "banding effort" from one year to the next. However, despite any annual variations in bander activity we believe things "average out" over time, and even without knowing actual hourly investment our long-term banding studies still provide broader understanding of nature trends here in the Carolina Piedmont. Year-to-year differences in actual work-hours DO affect our banding results, but of greater significance is how the Center's overall landscape has changed during 40 years we've studied and resided here.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Under our laissez-fair land management philosophy, vegetational succession ensued and local habitats passed through stages, first from old field to shrubland (mostly invasives such as Chinese Privet and Russian Olive) and then to a dense stand of Eastern Red Cedar by about the 12th year. By Year 20 or so, many cedars were shaded out and killed by fast-growing deciduous trees such as Sweetgums, leading the transition to our current young forest of pine and sundry hardwoods with minimal shrubs or herbaceous ground cover. (We continue our never-ending effort to whack back invasives such as privet and toxic Nandina.) An aerial photo of Hilton Pond Center from March 2012 (above) shows how thoroughly the land had become covered by woody vegetation--mostly Loblolly Pines on the north edge, and hardwoods between the two ponds and on the southern half and eastern end of the property.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Deciduous trees these days at the Center are quite diverse with lots of Winged Elm and Sweetgum; scattered throughout are Black Cherry, Green Ash, Hackberry, Flowering Dogwood, Red Maple, Box Elder, and various oaks and hickories. Several Baldcypresses have become well-established along the pond margin and are producing progeny. Just as vegetation has changed (current winter photo, above, with the pond barely visible), so has local bird life; with regard to banding, many species that hung out in vegetation close to the ground where our mist nets could snare them now fly uncaptured in treetops high above.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center It did not help our local bird life that in 1995 an adjoining farmer to the north of the Center clear-cut about 45 acres of mature Loblolly Pines and converted his land to pasture for beef cattle (see archival aerial image above). This apparently caused a nearly instantaneous drop in numbers of species that frequent pine lands, with populations declining drastically among numerous breeding species such as Blue Jays, Pine Warblers, and Brown-headed Nuthatches. Wintering species such as finches undoubtedly were affected by the loss of extensive cold-weather cover.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Speaking of vegetational change, Google Earth posted an aerial image (above) from January 2021 that shows the Center's old farmhouse and two massive fallen trees that were 125-150 years old. A giant White Oak (now a pale skeleton on the pond margin, at left in photo) snapped near its base in October 2014; an even taller Southern Red Oak (closer to the house and still covered by dark bark in the photo) tipped over violently on Easter weekend 2020. We feel quite certain the demise of these two towering canopy trees has had negative impact on Center avifauna, especially since all that missing leaf surface no longer hosts caterpillars that fueled the activities of migratory and resident birds. Two positive aspects: 1) Departure of the two big oaks created new "holes in the sky" that provide a better view of sunsets AND of birds flying over; and, 2) We got lots of "free firewood" to feed the farmhouse woodstove. (On the personal side, losing these two venerable citizens of Hilton Pond Center was heart-wrenching--but that's the way nature works.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Supplementing nature, on a year-round basis we offer local birds a LOT of food, primarily black oil sunflower seeds (above, with American Goldfinch, Carolina Chickadee, and Tufted Titmouse), plus white millet, cracked corn, shell corn, safflower, thistle (Nyger), dried mealworms, bark butter, shelled and unshelled peanuts, and various suet blocks. Our experiments with orange slices and grape jelly have failed to attract anything, including sought-after orioles. Spring through fall we hang at least two dozen feeders with sugar water for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds; in anticipation of western vagrant hummer species, we also maintain a couple of these even during winter. (NOTE: We've captured and banded two fall Rufous Hummingbirds locally.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Of equal or sometimes even greater importance than feeders, Hilton Pond itself and several much smaller artificial pools near the old farmhouse provide places for birds and other wildlife to drink and bathe. Accessible clean water often brings in more birds than does food--especially in winter when many drinking sources are frozen solid. This is why we place a cold-weather heater in at least one of our water features (bird bath, above, with three Eastern Bluebirds, a House Finch, two Northern Cardinals, and an American Goldfinch). Incidentally, it's a good idea to place bathing containers close to the ground and near vegetational cover--shrubs, vines, or small trees--that provide an escape route from predators when a bird's feathers are wet and less able to support flight.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One unusual aspect of the 2021 banding year actually began in late 2020 with that unprecedented influx of Pine Siskins. As might be expected when hundreds of birds flock and feed together at feeding stations, chances of disease transmission greatly increase--and that's just what happened at many spots across eastern North America: Bird enthusiasts reported sick and dead finches at their feeders. Most affected were Pine Siskins (above, with probable salmonellosis) and House Finches (below, with mycoplasmal conjunctivitis), although a few other species were also reported as victims.

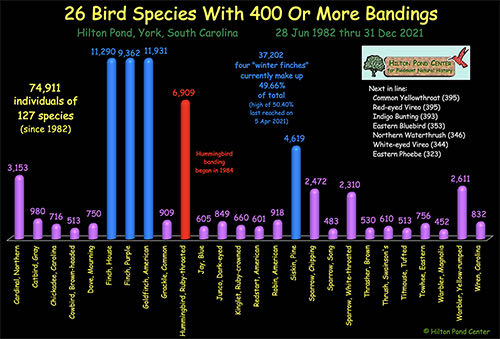

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The dual epidemics were so serious state non-game biologists in the Carolinas and elsewhere advised removal of feeders until the diseases had run their course. We kept the Center's feeders scrupulously clean and encountered only a half-dozen sick birds among 231 House Finches and 1,316 siskins (see chart below) banded all winter. In Autumn 2021 we did not see as many House Finches or American Goldfinches as typically occur at Hilton Pond Center when cold weather begins to arrive. We suspect this was due, in part, to the previous winter die-off from salmonella and conjunctivitis within those species. NOTE: Clicking on the siskin chart below--and all others that follow--will open a larger, more legible version for you to evaluate more easily. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center ••2021 BANDING DETAILS•• As shown on the chart below, the 2021 banding period was quite different from our norm at Hilton Pond Center. The year started very fast, largely because of the winter finch influx. In January alone we banded 83 Pine Siskins (PISI) and 82 Purple Finches (PUFI), but that was almost piddling compared to February's 600 PISI, 89 PUFI, and 101 American Goldfinches (AMGO)! Although things finally slowed down a little in March, by the end of that month we already had banded 1,703 birds (22 species) in 2021--pretty amazing when in 19 of our 40 years at the Center we had a lower banding tally than that for the entire year. (NOTE: As anticipated, after their unprecedented high numbers in the winter of 2020-21, not one siskin appeared at Hilton Pond in Fall 2021--typical for a season following a big irruption.) All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The 2021 banding season ended with 3,109 birds banded from 81 species for Hilton Pond Center. These numbers were well above the 40-year average of 1,872.8 individuals (dotted white line on chart) and the species average of 65.7. (The chart's dotted red and blue statistical regression lines show an on-going moderate decline in both these categories.) This year's total was slightly more than three-quarters of what we caught in our most productive year of 1991 (4,061 individuals); diversity in 2021 was quite good but somewhat less than the record 95 species we caught, also in 1991. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The chart above shows 40-year cumulative totals for the 26 species banded most often at Hilton Pond Center. American Goldfinches continue to lead the way with 11,931 bandings since 1982; they are ahead of House Finches (11,290) and Purple Finches (9,362) by relatively small margins. These three species plus Pine Siskins (4,619) are what we call the four "Winter Finches" (although HOFI and AMGO do occur here year-round, the latter in small numbers); the four totaled 37,202 bandings by the end of 2021, i.e., nearly half (49.66%) all birds captured. We always find it interesting the target species for our most intensive long-term study--Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--is the fourth-most-commonly banded species at the Center with 6,909 captured (since 1984). (Our sugar water feeders and plentiful nectar flowers undoubtedly play a role in local hummingbird abundance.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As shown in RED on comprehensive Table 2 at the end of this narrative, six species banded in 2021 at the Center exceeded or tied previous annual highs--including the state-record Broad-tailed Hummingbird mentioned above. Then there were those multitudinous Pine Siskins whose 988 bandings greatly exceeded the previous record of 770 set back in 2015. Tying records were Downy Woodpeckers with 18 (first reached in 1994) and Blue Grosbeaks (adult male, above) with six (matching 1986, 1992, 1993, and 1994), while Bay-breasted Warblers came in with 12 bandings, notably exceeding five from 2017.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Two species tied records with one each: Orange-crowned Warbler (immature of unknown sex, above) and Blackburnian Warbler (immature female, below). These warblers are among the rarest captures at Hilton Pond Center, with just five of the former and three of the latter banded locally in 40 years.

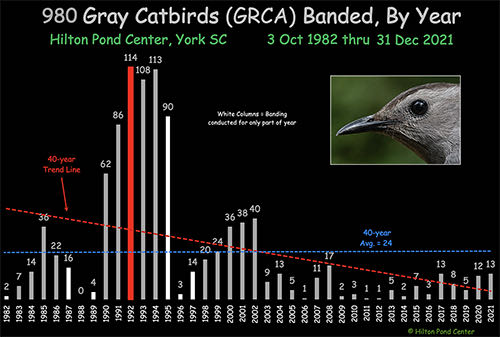

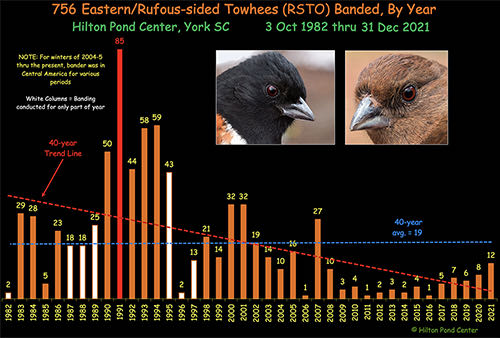

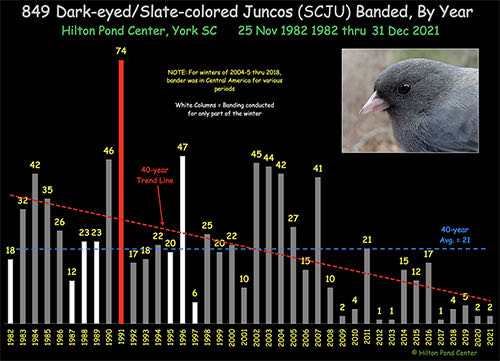

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Of perhaps greater significance than these new/tied records were the 55 species whose numbers TIED OR EXCEEDED 40-year AVERAGES--some by a considerable margin. Of particular note were those 988 Pine Siskins (almost a magnitude more than their average 115); 320 Purple Finches (42% above of an average 234); and 279 Yellow-rumped Warblers (nearly five times the average of 65). Northern Cardinals showed a continuing rebound for a species whose numbers dropped precipitously in the early 2000s; 104 bandings this year came in above the average of 79. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center It's likewise worth mentioning some of our BELOW-AVERAGE species--especially a few that we've banded at much higher levels in past seasons (Gray Catbirds, for example; see chart above). In 2021 we banded 13--under the 40-year average of 25 and barely a tenth the all-time catbird high of 114 from 1992. And consider our Eastern Towhees (see chart below), whose 12 bandings this year were the best since 2007 but still far under the 85 we handled in 1991. Incidentally, a third species that breeds locally but showed lower numbers than usual were Brown Thrashers; we banded six when expecting 13 (the average) and coming nowhere near the 1993 record of 59. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center And then there are Dark-eyed Juncos (see chart below), which until about 15 years ago were among the most common winter residents beneath feeders at Hilton Pond Center. Most years we'd band about two to four dozen, but their numbers have plummeted and this year we caught just two "snowbirds"--a far cry from 74 in 1991. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Might catbirds, towhees, thrashers, and juncos have something in common that led to precipitous banding declines? Well, all are birds of shrubby or weedy areas and in the past 40 years such habitats have gradually disappeared around the Center, so that's a possible explanation. There's also evidence the first three of these species were hit especially hard in the 1990s by West Nile Virus, while it may be juncos simply aren’t coming this far south these days because of warmer winters on breeding grounds up north. But who knows for sure? Cause and effect are always difficult to connect in nature, so all this is just speculation on our part--even though we remain ever hopeful our continuing long-term studies eventually might provide even better hypotheses. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Also of interest was a Common Grackle fledgling (below right) banded in June 2021--the first COGR captured at the Center since 2018. Folks often ask: "What's the most unusual bird you banded this year at Hilton Pond Center?" We're never quite sure how to answer except to look at numbers and respond with the name(s) of species we seldom band.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Using that criterion, that state record female Broad-tailed Hummingbird (above) on 20 September 2021 would be a given, but the Blackburnian Warbler captured seven days later would likely come in next as just the third of its species in 40 years. Our third "most unusual" capture was a hatch-year Baltimore Oriole (below)--just our eighth banded since 1982.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In addition to the three especially rare species just mentioned, several others encountered in 2021 have been banded fewer than 60 times during four decades at the Center. Their portraits and tallies are below.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Red-winged Blackbird (above), adult male in winter plumage; surprisingly uncommon locally, with just 29 banded in 40 years. (Once or twice each winter we see a flock of several hundred or more.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Sharp-shinned Hawk (above), immature female mist-netted in February; our 41st. Most (76%) have been banded October through December.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of three Great Crested Flycatchers (above) captured in 2021; total of 59 banded since 1982. This species has nested in one of our Wood Duck boxes.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of three Brown-headed Nuthatches (above) netted or trapped in 2021; total of 56 banded since 1982. Somewhat more common in previous years before that neighboring Loblolly Pine forest was harvested.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center White-breasted Nuthatch female (above); our 33rd. An uncommon year-round resident. (Males typically have a blacker crown.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Orchard Oriole female (above); our 57th. Likely breeds locally but we've not found a nest.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Yellow-bellied Sapsucker (above), our 55th; a regular winter visiting species that attacks one of the Center's Pecan trees. (One this fall has also been attacking a bathroom window in our old farmhouse.) Females lack the red chin of the male.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Fox Sparrow (above); our 47th. An uncommon winter visitor that often shows up beneath Hilton Pond feeders when it snows.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of two Blue-headed Vireos (above) captured in 2021; total of 20 banded--all but one in autumn migration..

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of two Black-throated Green Warblers (above) banded in 2021, with 26 since 1982--all but one captured in fall. Apparently increasing locally during migration, with seven banded in the past three years.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of two Canada Warblers banded this year, spring male above--our 34th. Migrant at the Center, with 90% of bandings during fall.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Kentucky Warbler (above), our 21st. Possible local breeder, but no nests found.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Prairie Warbler (above), our 40th. Likely a local breeder when the Center's property was more open; now quite scarce, with our most recent previous banding in 2007.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Worm-eating Warbler (above); our 53rd. Possible local breeder, but no nests found.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Louisiana Waterthrush (above); our 59th. Breeds locally, based on captures of several fledglings and of females with active brood patches.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Hairy Woodpecker (immature female, above). Seldom observed locally, among bandings since 1982 the species is greatly outnumbered by Downy Woodpeckers 271 to 30. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center ••2021 FOREIGN ENCOUNTERS•• Northern Cardinals, Carolina Chickadees, Tufted Titmice, Carolina Wrens, and Mourning Doves, among others, are year-round residents at Hilton Pond Center. We recapture many of them over and over again after banding. Other species are non-residents that migrate away after the banding season, never to be seen again. A few return in one or more later seasons as excellent examples of precise site fidelity. Others show up far away and are encountered by banders or other citizens who report them to the U.S. federal Bird Banding Laboratory clearinghouse in Laurel MD.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our furthest known flier to date was a brown Purple Finch (file photo above) of unknown age banded at the Center in Feb 2004 and encountered two months later at Monastery, Nova Scotia--where it had been killed by a cat. This was a sad way to end a northbound migration route that covered at least 1,275 straight-line air miles. Despite banding 74,911 birds during four decades at Hilton Pond Center, only 68 individuals (14 species) have been encountered outside our home county of York SC, while an additional 46 (13 species) were reported from within the county. (Click on links to review either list in a new browser window.) We speculate such low foreign encounter rates are due in part to a relative scarcity of banders in the southeastern U.S. and because of the mostly rural nature of the Carolinas; fewer banders, fewer people, and large swaths of undeveloped land mean banded birds are less likely to be encountered. Although many years the the Bird Banding Lab sends the Center no reports of foreign encounters of our banded birds, the just-completed 12 months turned out to be relatively productive, as follows:

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

Six additional Hilton Pond bandings were found dead within York County in 2021 and reported to the Bird Banding Lab by the finders--some within just a few miles of the Center. These included: Three Pine Siskins (banded 2020 or 2021), Northern Cardinal (banded 2019), House Finch (banded 2018), and Carolina Chickadee (banded 2019).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Reports of birds banded here at the Center and encountered elsewhere are indeed rare, but even more uncommon are individuals banded by someone else and recaptured at Hilton Pond. This has happened just ten times in 40 years, the latest a banded Pine Siskin (above) we re-trapped in February 2021.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Upon reporting this siskin to the Bird Banding Lab we learned it had been banded and released as a hatch-year female three months prior in November 2020 at Foreman's Branch Bird Observatory near Kingstown MD (see map above), 412 miles to the northeast! (In an amazing coincidence, two American Goldfinches banded at Hilton Pond were recaptured and released at Foreman's Branch in 2010 and 2011!) All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center ••2021 RETURNS & RECAPTURES••

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As noted, during our 40 years of research we've had thousands of local recaptures of birds banded at Hilton Pond Center in previous seasons. Many year-round residents (Tufted Titmice, above, and chickadees, for example) are "trap junkies" we catch over and over again, while others are seldom-seen migrants that return after a breeding season at some far-flung locale. Some notable returns and recaptures are described below.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center ••2021 RUBY-THROATED HUMMINGBIRDS••

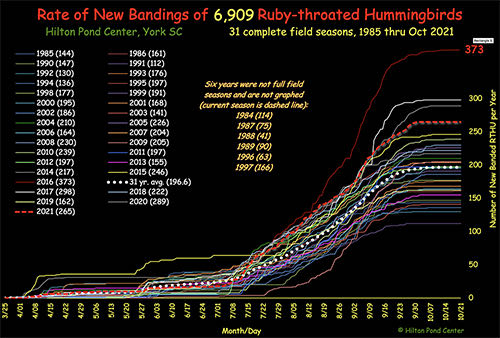

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (RTHU, immature male with partial gorget, above) again rebounded nicely in 2021 at Hilton Pond Center after an unexplained downturn in banding results two years ago (see chart below). For the 13th time we exceeded 200 annual bandings and had our fourth-most-productive season with 265--finishing well above our 38-year average of 182. (NOTE: Because of special federal permit requirements, RTHU research did not commence until July 1984--two years after other local banding activities began. Thus, 2020 was our 38th study season for hummers, compared to 40 for other species.) All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our first Ruby-throated Hummingbird of 2021 was a banded male that arrived on 29 March, three days later than our earliest ever. (Early arrivals are always males, and in nine of 38 years they have appeared between 26 and 30 March.) The first unbanded male RTHU was captured on 5 April, with the first new female on 15 April. (Our earliest-ever unbanded female came on 8 April 2002.) The moral of this story is we begin stocking multiple sugar water feeders by St. Patrick's Day (17 March) each year--although we do maintain a couple of feeders all winter in hopeful anticipation of western vagrant hummingbirds that rarely appear.

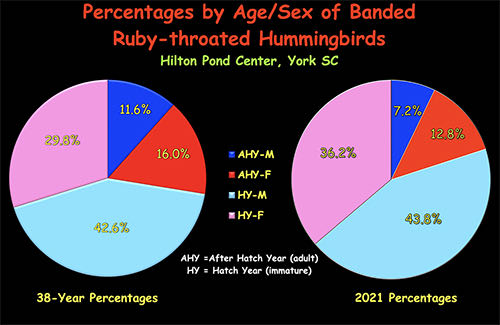

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center NOTE: To justify our policy of providing year-round sugar water feeders, we'll mention we've captured two vagrant Rufous Hummingbirds at Hilton Pond Center: An early hatch-year male on 23 September 2002 and a hatch-year female on 20 November 2001. The latter (above) was re-trapped and released in Columbus OH on 29 November the following year! All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center But back to Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. The 2021 season started rather slowly--its progress is marked by the red dashed line on the chart above--with only nine RTHU banded by the end of April. This was a typical number for that date, although by then in 2014 and 2015 we had banded 31 and 36, respectively. May was unusually slow with only six bandings for the entire month, and June was worse with just three; we were beginning to think 2021 could be a really poor year for hummers. Things finally began to pick up with capture of the first fledgling ruby-throat of the year--a young male on 5 July. After that we were off and running with 70 bandings in July and 79 more in August--giving us one of our most productive summers (see red dashed line on chart). As usual, the first two weeks of September were our boom time before things slowed to a crawl. Surprisingly, October was nearly a bust with just one banding on the first day, but with 265 RTHU banded as the season ended we still finished with our fourth-best total in 38 years of study. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center By the end of any given breeding season at Hilton Pond Center we logically expect many more hatch-year RTHU among our banded birds. During 38 years (left pie chart, above), 72.4% of all ruby-throats banded have been recent fledglings (males in pale blue, females in pink); in 2021 (right pie chart) they made up significantly more at 80.0%. Our 116 hatch year males comprised nearly half (43.8%) of all bandings in 2021--above the 38-year average of 42.6%; by comparison, 99 young females resulted in a significantly higher percentage (36.2%) than average (29.8%). Percentages for 19 adult males (7.2%; dark blue on pie charts) were noticeably lower in 2021 than the 37-year average of 11.6%. Such was also the case for 34 females (12.8%; in red), below the average 16.0%. In short, adult birds were considerably fewer than expected, which could have had an effect on overall breeding success in 2021.

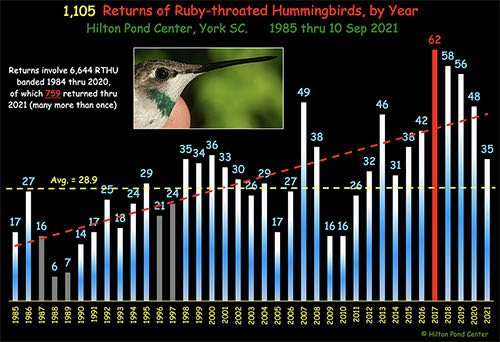

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of the most fulfilling things about working with Ruby-throated Hummingbirds is putting bands on their legs and seeing them come right back to Hilton Pond in later years, having traveled perhaps 2,000 miles to Central America--and back. Even after nearly four decades, we are amazed how a creature that weighs half as much as a nickel can be successful at such long-distance migration. That's why we were a bit disappointed when we had only 35 RTHU returns in 2021 (see chart above)--our fewest since 2015 and barely half our record of 62 set in 2017. With 6,644 hummers banded at the Center through last year, this season's returnees brought our 38-year total to 1,105; that number actually involves 759 individuals, since many ruby-throats returned more than once. A quick calculation shows 759 of 6,644 is a return rate of 11%, which at first blush seems quite low. However, when one considers an estimated 60-80% of each year's young hummers fail to make it through their first winter, 11% survival and eventual return to Hilton Pond Center is pretty substantial--plus it's likely some RTHU return here and are not recaptured. Ruby-throated Hummingbirds do indeed have a high die-off, what with the dangers of migration, predators, window strikes, disease, bad weather, genetic deficiencies, and other factors, so we're very pleased with our overall 11% return rate. (NOTE: The dotted red trend line on the chart above shows RTHU returns are generally increasing at the Center--to be expected because our numbers of new bandings are also on the rise. We can't determine whether actual survivability is improving.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Of the Center's 35 RTHU returns in 2021 (see Table 1just below), 17 were banded last year (2020), 10 in 2019, two in 2018, three in 2017, two in 2016, and one in 2015. TABLE 1: #81279--08/08/15--after 7th year female (16,17,18,19,20,21) All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our oldest returning Ruby-throated Hummingbird this year was a female banded as an adult in 2015 and recaptured every year since. She is now an after-seventh-year bird in at least her eighth year and could be even older. (The Bird Banding Lab's record for oldest free-flying Ruby-throated Hummingbird is nine-plus years.) Another female RTHU returning in 2021 (in GREEN on the chart above) was banded in August 2016 and not encountered again at the Center until last year; now an after-6th-year bird, she likely was in the vicinity during the summers of 2017, 2018, and 2019 but we just didn't catch her.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Perhaps the most striking aspect of the list above: Among 35 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds returning in 2021 only five were males (highlighted in BLUE)--and only one of those had been banded as a red-gorgetted adult (above). This is difficult to explain, but we have considered three possibilities below, the second of which we believe is most likely. (We're happy to entertain other hypotheses. If you have one, please click here to send an e-mail to us at INFO.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One final note about the Center's Ruby-throated Hummingbird returns in 2021: Only two had been banded in September and none in October during previous years--a phenomenon that happens regularly at the Hilton Pond. We suspect this is because the vast majority of late-summer bandings are young birds that very well may be pass-through migrants from points further north. If these individuals--including the color-marked hatch-year male pictured above with partial red gorget--survive their first southbound migration, they may return to some distant natal range rather than to Hilton Pond. It's also possible many September/October bandings are late-fledging, late-departing youngsters that aren't as strong and well-developed as RTHU that had been around all summer; as a result, they simply don't make it through their first migration south. (Again, we welcome alternate hypotheses on this situation at INFO.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Please note that all Ruby-throated Hummingbirds captured--or recaptured--at Hilton Pond Center are banded and then marked with temporary, non-toxic green dye on lower throat (see adult female above). This helps us avoid recapturing "trap junkie" hummers that re-enter our pull-string and electronic traps over and over and over again. Come spring it also means folks north of us can be alert for color-marked RTHU from the Center; in autumn observers to our south can be on the lookout. If you see ANY color-marked hummingbird, please report it to us immediately via e-mail at RESEARCH; a photo would be most helpful.

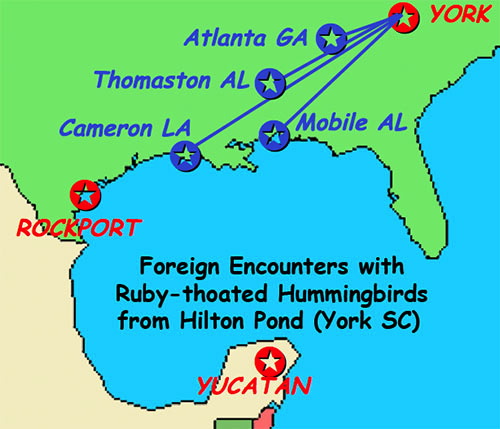

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Alas, only six of our Hilton Pond hummers have been seen elsewhere, and most were reported because they were color-marked. Four RTHU were encountered during fall migration (see map above) in Atlanta, Louisiana, and Alabama (two individuals). Two spring migrants were reported from Massachusetts and Clover SC (the latter about ten miles north of the Center). All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center ••2021 "YARD LIST" & NESTING SPECIES•• Our inventory of birds observed through the years on, over, or from Hilton Pond Center rose by one to 173 in 2021, when we mist-netted that state record Broad-tailed Hummingbird in September. We saw or heard a total of 111 bird species at the Center--tying our record set last year. This year's tally represented more than half (64%) the species observed locally since 1982.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We find it interesting that of 38 North American Wood Warblers LIKELY to be seen at Hilton Pond Center, we have observed and banded 35 of them (including the male Black-throated Blue Warbler, above). The missing species are Cerulean Warbler and Mourning Warbler--both of which typically migrate further inland west of the Center--plus the endangered Kirtland's Warbler. (The other 14 extant North American parulids are western species not likely to occur in South Carolina's Piedmont Province. Bachman's Warbler--now "officially" extinct from the Carolina Lowcountry and elsewhere--can no longer be seen except in museums.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Among all species encountered at the Center since 1982 we've found nests for 25, including other birds that often lay their eggs in a box intended for Eastern Bluebirds (winter male and female above). A male Prothonotary Warbler even tried building a nest in a box with 1.5" hole before a dominant bluebird pair drove him away. All our boxes have been fairly effective and have been used by Tufted Titmice, House Wrens, and Carolina Chickadees. We've also installed several boxes with 1" diameter holes that exclude bluebirds but allow Brown-headed Nuthatches to enter. Boxes stay up year-round and sometimes serve as roost sites during cold weather; they occasionally are occupied by Southern Flying Squirrels and once by a Golden Mouse.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We have six much-larger nest boxes mounted on poles in the water around Hilton Pond itself. Complete with predator baffles, these structures are designed for Wood Ducks (hen and young, above) and have produced more than 850 ducklings since 1982. NOTE: If you're not keeping a "Yard List" for your own property we encourage you to do so, and to report your sightings via eBird. The eBird Web site provides a great way for you to keep track of what you see and when, and it allows you to make valuable contributions to our body of knowledge about birds. You, too, can be an ornithological "citizen scientist." All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center ••2021 CUMULATIVE BANDING RESULTS•• A complete list of 3,109 birds of 77 species banded at Hilton Pond Center in 2021 is in the table below. Also shown are our 40-year maximums and averages, plus grand totals for each species. We invite you to examine and dissect our data table below and narrative above for trends or to see whether we captured your favorite species. For a running account of banding and recapture results for the just-completed year, please refer to lists at the end of each installment of "This Week at Hilton Pond," beginning with 1-31 January 2021. There really is much to be said for long-term banding projects like ours that provide solid baseline data leading to better understanding of avian ecology. We're proud to report we've been at it since 1982 at Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History--still the most active year-round bird banding station in the Carolinas. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

Checks also can be sent to Hilton Pond Center at: All contributions are tax-deductible on your TABLE 2: The list shows all 128 bird species banded locally since 1982;

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Don't forget to scroll down for lists of all birds banded and recaptured during the week. HILTON POND SUNSETS "Never trust a person too lazy to get up for sunrise

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Sunset over Hilton Pond (above), 24 December 2021

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Sunset over Hilton Pond (above), 27 December 2021 Photoshop image post-processing for this page employs |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Dr. Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

|

When we purchased our 11-acre plot in 1982 it was almost all open (pond is at left in photo at right), the result of a century of agriculture that apparently involved cattle grazing and planting row crops such as cotton, corn, tobacco, and soybeans.

When we purchased our 11-acre plot in 1982 it was almost all open (pond is at left in photo at right), the result of a century of agriculture that apparently involved cattle grazing and planting row crops such as cotton, corn, tobacco, and soybeans.

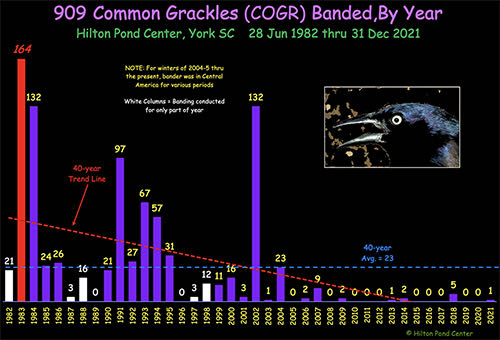

This is a seemingly odd phenomenon because grackles are so widespread in the Carolina Piedmont and appear especially abundant in winter flocks numbering in the thousands. However, field studies indicate grackle populations declined by 50% during the past four decades, likely from loss of habitat and overuse of agricultural and homeowner pesticides that destroy insect prey. Our local results reflect this decline

This is a seemingly odd phenomenon because grackles are so widespread in the Carolina Piedmont and appear especially abundant in winter flocks numbering in the thousands. However, field studies indicate grackle populations declined by 50% during the past four decades, likely from loss of habitat and overuse of agricultural and homeowner pesticides that destroy insect prey. Our local results reflect this decline