- Established 1982 -HOME: www.hiltonpond.org

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

GNATCATCHERS, COWBIRDS, AND We know it's really spring at Hilton Pond Center when we spot our first Blue-gray Gnatcatcher (BGGN) of the year (photo below). Such was the case on 31 March when one of these hyperkinetic little birds appeared after spending the cold months along southern U.S. coastlines or somewhere in Mexico. Historically, BGGN nested in subtropical areas of North America but are advancing northward and now breed as far north as the Great Lakes. This is a fairly recent range expansion likely due to climate change and higher average temperatures.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Some folks have likened BGGN to miniature Northern Mockingbirds because of a gray body and long white outer tail feathers (above) they flick constantly while foraging for insects. Despite any similarities to mockers, Blue-gray Gnatcatchers are in the Polioptilidae (Gnatcatcher Family) not the Mimidae (Mimic Thrush Family) and are more closely related to wrens. Incidentally, adult male BGGN (above) have a black superciliary line lacking in females.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Each year gnatcatchers are preceded at the Center by a less welcome influx of Brown-headed Cowbirds (BHCO), usually in late March in groups of two or three males chasing a female. The species is named for the male (above) with its chestnut-colored head, shiny black body, and sharply pointed conical black bill. Female cowbirds (below) are among the most nondescript birds in North America, and many novice birders have trouble identifying them. The female's body is a mousy grayish-brown but the distinctive black mandibles still say Brown-headed Cowbird. (Repeat: Look for that stout black bill.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Like many ornithologists, we have mixed feelings about cowbirds because of their propensity for laying eggs in the nests of other species--maybe even Blue-Gray Gnatcatchers that typically fail to recognize a cowbird egg among their own clutch. As social parasites BHCO are known to take advantage of about 220 bird species, at least half of which have ended up raising cowbird foster chicks--often at the expense of their own. One hypothesis is that Brown-headed Cowbirds evolved in the Great Plains following herds of American Bison to forage on stirred-up insects, eventually losing nest-building genes and now depending entirely on sedentary host species to propagate. Another interpretation is that BHCO arose in the Neotropics, where their nest parasitism became a successful strategy they brought with them as they radiated north. In any case, cowbirds these days have a stable North American population, so there's no question their brood parasitization is an effective adaptation that some folks admire for its evolutionary success.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although we occasionally see BHCO (above) within massive winter flocks of Common Grackles, Red-winged Blackbirds, and European Starlings, come late March local cowbirds mostly just show up here in those small groups. They frequently enter our ground traps containing mixed seeds, but the best way to snare male cowbirds is to catch a female first and let her be bait. The species does not form pair bonds and both sexes copulate promiscuously, with males constantly chasing receptive females throughout the breeding season. A female Brown-headed Cowbird may lay a dozen or more eggs, take a break, and lay a dozen more. After females drop those eggs in other birds' nests all our Hilton Pond cowbirds literally disappear by mid-summer: In 42 years of banding at the Center we've banded 558 BHCO--but only SIX of them July through December! All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center BLACK VULTURE NEST IS NO MORE To summarize and expand upon our earlier reports: On 20 February at Hilton Pond Center we observed a Black Vulture strutting on the metal roof of an abandoned chicken coop about 30 yards from our old farmhouse. As we watched from our office window, the vulture dropped to the ground and disappeared behind the far end of the shed. Curious about where the big black bird had gone, we later entered the structure and spooked the vulture, which flew out through a big hole in the coop siding. Left behind in a nest scrape on the hard concrete floor were two three-inch mottled greenish eggs (below) the bird must have been incubating. To minimize disturbance, we retreated from this nest area and took a station some distance away. From there we saw the Black Vulture re-enter the chicken coop.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The situation presented what we thought could be an interesting opportunity to observe Black Vulture reproductive behavior. Folks elsewhere have set up remote cameras at nests of Bald Eagles and Peregrine Falcons, but not many have showcased Black Vultures with webcams. Thanks to a financial gift from a major supporter of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History, we immediately ordered a surveillance camera, laptop, Ethernet cables, and associated equipment and--within a week or so--had established a YouTube livestream depicting what was going on in the dim recesses of our ramshackle chicken coop, now elegantly dubbed "Chez Vautour Noir."

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One big glitch occurred as we were running Ethernet cable on the ground from our desktop computer to the camera in the chicken coop. Within hours it seems one of our local Eastern Cottontails perceived the 100-foot-long red cable as some sort of delicacy and completely bit through the wiring (above)--not once, but twice!--requiring we run new lines (at twenty bucks each). After the second severing we threaded the cable through a couple lengths of metal electrical conduit in the vegetated area where the rabbit had been doing its work. We also coated the wire with nasty-tasting Bitter Apple spray. Dang rabbits!

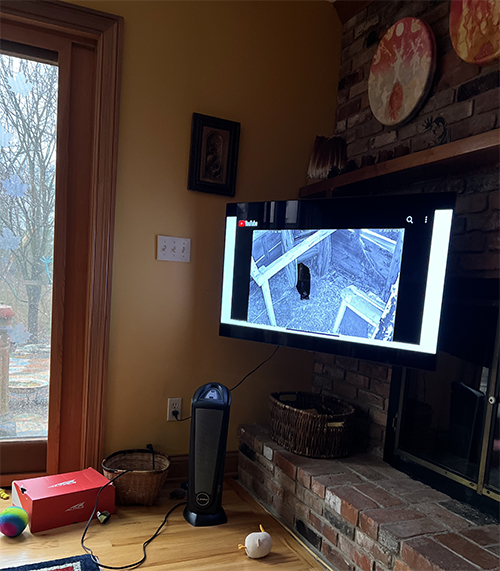

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Eventually the livestream from the vulture nest caught on and folks around the country began watching. One couple in Ohio told us they even projected the YouTube video on a big screen TV (above) so they could stay up-to-the-minute on what was happening in the ol' chicken coop. (And no commercials, they said!)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Most of the livestream was near-countless minutes of a Black Vulture simply sitting and incubating--punctuated by footage of the bird stretching (above), preening, and defecating. (The camera's infrared capability even showed what was happening during dark of night, and that was not much.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Roughly every 24 hours, a second vulture would enter the scene and the pair would go through a ritual of head- and bill-rubbing and neck preening (above) before the new bird took over egg-sitting duties. Any sort of movement at the nest put the camera in "record," sending video snippets to our desktop computer. We collected these and posted them sequentially to YouTube, complete with interpretive commentary. Still images from these snippets are included above and below.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The livestream continued day after day, night after night as parent vultures took turns incubating, with one bird to departing to stretch its wings and forage on some distant offal while the other tucked in its head and took a snooze (above). Considering the incubation period for Black Vultures is an estimated 30-38 days, we figured hatching was imminent by the last week in March and expected any moment to welcome baby vultures into the world. Alas, that was not to be.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Early afternoon on 23 March, as we were watching the livestream in real time, what seemed to be a third Black Vulture (with distended crop, above) entered the nest area in the chicken coop. The new bird went straight to the incubating vulture, which seemed quite nervous but attempted the usual head and bill rub greeting ritual. The new bird wanted none of this, pushing the incubator off the eggs and immediately tossing them roughly around the shed with its bill. We were stunned.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The incubating vulture made feeble, mostly unsuccessful attempts to cover the eggs but seemed helpless during the assault and egg-toss. Eventually both birds left the scene, so we decided to re-enter the shed and check on the two eggs (above). One seemed intact but the other was cracked. We gathered them and placed them together in the nest scrape, then retreated to see what might happen next.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Within a few minutes the incubating vulture returned to duty, followed in short order by the more aggressive bird. The scenario repeated, with the interloper pushing the incubator around and violently tossing eggs. After about eight minutes of disruption, both vultures departed and we entered the chicken coop to examine the eggs again. The cracked one was damaged even more (above) and we couldn't really discern its contents but the other seemed undamaged; once more we placed them together in the scrape and exited. (NOTE: We doubt our presence or our handling of eggs had any impact of the behavior of any of the adult Black Vultures. Our visits to examine the ransacked eggs was our first to the chicken coop since we set up the camera.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Following our departure, the incubating vulture hopped into the shed one more time and incubated both eggs, this time almost all night. About 5:25 a.m. on 24 March, however, the incubator suddenly dragged the badly broken egg away from the scrape and began eating the contents (above)--apparently a partially developed chick--leaving some behind before walking out of the field of view. All this was happening in the dark before dawn and was revealed by the infrared camera.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A vulture appeared soon after, finishing off what was left from the first egg and shifting attention to the second, rolling it around and eventually pecking at it and breaking through the shell (above). For the next 90 minutes this vulture sampled contents of Egg #2, preened and wandered about the coop, pushing sticks and other vegetation from one spot to another--perhaps waiting for daylight--and eventually departed. Over the next several daylight hours and again the next day (25 March) at least two different Black Vultures returned individually and/or together to inspect the nest area. A solitary bird showed up on the 26th (see photo below) but video recordings revealed no more vulture visits after that.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center So one might ask: "What the heck happened?" We don't have any definite answers, in part because Black Vultures all look pretty much alike--especially in low resolution video snippets. Were there two attentive parent vultures and then an interloper that attacked its competitors' eggs, which we suspect. Or did one parent bird decide the eggs were dead or perhaps just get tired of incubating? After all, both eggs were at least 35 days old, with typical incubation expected to take less than 40 days. (It's worth noting there were six cold, sub-freezing nights in mid-March when those eggs--despite being covered by a warm, incubating parent--were sitting on the shed's hard concrete floor. That's a situation that might chill an embryo enough to permanently stop development.) The above are possibilities about what led to nest failure, but maybe something else was going on about which we simply don't have a clue. There may be too many variables and insufficient information to draw a definitive conclusion, of course, so for now we'll let the matter rest as The Mystery of Chez Vautour Noir: An Unexplained Black Vulture Nest Failure. We invite you to examine the Black Vulture Nest Cam video snippets on YouTube and to suggest in a message to INFO any alternative explanations you might derive.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Mystery or not, on the plus side Hilton Pond Center now has a nice infrared surveillance camera, a dedicated MacBook laptop, several hundred feet of Ethernet cable, power injectors, switches, extension cords, and ancillary equipment (to say nothing of hours and hours of video footage). We're all set if the Black Vulture pair (above) returns to try again in 2024--or if some other natural phenomenon suitable for livestreaming should pop up.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Just in case, the surveillance camera is still running--the livestream is not--sending snippets to our desktop computer when anything occurs in the Black Vulture nest area. The species is known to re-nest after a failed clutch, but that had not occurred through the end of March. And who knows what else might go on in the dark recesses of Chez Vautour Noir--like maybe a visit from a night-wandering Didelphis virginiana (above). ========== POSTSCRIPT: The empty shell from Egg #1 still sits in the nest scrape. Seems like it would be a good source of calcium for some wandering rodent that might enter the shed. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center HILTON POND SUNSET (AND OCCASIOINAL MOONSETS) "Never trust a person too lazy to get up for sunrise

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Sunset over Hilton Pond, 24 March 2023 Under a clear sky the sunset was pretty straightforward on 24 March, so we waited a few hours for the Earth's Moon and sister

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Sunset over Hilton Pond, 27 March 2023 High above the clouds, passenger jets traced white contrails across blue sky, but lower down angry clouds could not decide whether to unleash another lightning storm or pock the pond with a little Don't forget to scroll down for lists of Hilton Pond supporters and of all birds banded and recaptured during the period. Photoshop image post-processing for this page employs |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Dr. Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

|

Please report your spring, summer &

Please report your spring, summer &