|

|

|||

|

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Stanlee Miller has seen lots of hummingbirds--both around his backyard and inside little plastic bags in his freezer. (The former occurs because he's got feeders and plentiful nectar plants, the latter because--as Clemson University's Curator of Vertebrate Collections--he prepares study skins from specimens the public donates when hummers crash into picture windows and cars.) Stanlee gets the usual complement of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds lapping up sugar water at his feeders near the University, but attracted another hummer that first appeared on 2 November 2003 and was sighted fairly regularly thereafter. On 12 January Stanlee E-mailed to Hilton Pond Center a nice digital photo his 17-year-old son Nathan had taken of the bird, after which we quickly contacted the proud poppa to set up a banding excursion to Clemson (Pickens County SC) for the morning of 13 January.

Once again, we left York and stopped the night before at our in-laws in Greenville to shorten the morning drive, allowing us to be at the Miller house by 7 a.m. while still getting reasonable rest. Joining us for the trapping session were Clemson ornithology prof Dr. Sid Gauthreaux--a world authority on tracking migrant birds with radar--and another avid birder, his wife Carol Belser. We had brought along our newest high-tech hummingbird trap that uses a model car remote control radio device and servo motor to release the door. After placing Stanlee's feeder in the trap and hanging the contraption outside the window, everyone sat down in the study to await the winter vagrant hummingbird.

A couple of minutes later the door on the trap slid shut on its own without our touching the remote button, so we re-set the door, assuming a release pin had slipped out when the wind blew. Shortly thereafter the hummingbird zipped into and out of view without examining the trap, and repeated the now-you-see-me-now-you-don't behavior several times over the next 15 minutes. Everyone was pleased to see the hummer even if it didn't enter the trap, and keen-eyed Sid remarked that "The bird looks small." At that point the trapdoor mysteriously closed, requiring another re-set. Then the hummer came back and showed a little interest in the feeder. Then the trapdoor shut again by itself. Then we got befuddled and frustrated. Then the hummer came back while we were trying to re-set the trapdoor. Then we noticed the servo motor had taken on a life of its own, rotating back and forth with no input from our wireless transmitter--probably a sign that someone nearby was using an electrical device that caused interference and made the servo mechanism worthless. As a result, we regressed to our "old" low-tech way of trapping hummingbirds by attempting to attach a pullstring to the trapdoor. Now that we had a closer view of the bird in the trap, it first appeared it might be another immature female Rufous Hummingbird--certainly the most common western vagrant hummer in the Carolinas. Despite the bird's rather buffy sides, however, there didn't seem to be enough rust at the base of the tail (above left) to make it a Selasphorus hummingbird (i.e., a Rufous or the closely related Allen's).

Bearing out Sid's earlier observation from afar, the bird also felt a little small in the hand, but we didn't realize HOW small until we placed it on the electronic balance and weighed it at 2.5g--far below the 3.5g we would expect from a typical midwinter Rufous (see comparative photos below). Up close, Sid surmised that the bill seemed short--and it was, at 16mm. The tail was short, too--just 22mm--but its rounded shape was the final tip-off: we had just captured a Calliope Hummingbird.

Female Calliope Hummingbird (above) compared in size to

It is worth noting that the Clemson bird showed quite a bit of wear and tear on its wing (dorsal view below), and was bringing in several new secondary wing feathers. The complete absence of any iridescent lavender in the gorget--plus measurements and other characteristics--led us to conclude that the bird was a young, second-year female that hatched out sometime in 2003. Calliope Hummingbirds, Stellula calliope, are far scarcer in the region than our relatively abundant Rufous; in fact, fewer than ten Calliopes have ever been confirmed in South Carolina. One of these was a young male we banded on 21 Dec 2001 at Bethany--about ten air miles from Hilton Pond Center. (We also captured one three weeks later in Gastonia NC.) Greer SC seems to be the real hotbed for Calliopes; the state record bird was banded there in 2000 in a yard that has hosted at least three more since. Calliopes breed in the mountains of western North America and winter in central Mexico, so the Clemson bird is likely to be heading back in that direction sometime in the next month or two.

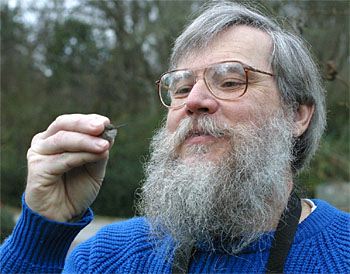

As we measured the bird and banded the right leg, it sloughed off a couple of loose tail covert feathers that almost certainly were due to be replaced in coming weeks. Fast as lightning, Stanlee grabbed them from mid-air and scooped them into one of those plastic bags he normally reserves for dead bird specimens. In this case, however, the Calliope Hummingbird was very much alive, and it was just a small sample of her plumage that would become part of Clemson's permanent collection of vertebrate artifacts. With the feathers securely bagged, we hand-fed the Calliope and photographed it for posterity, and Stanlee Miller (below)--the quintessential curator--sent it on its way.

Vital Statistics for All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

If you're interested in sharing your hummingbird observations and learning from other enthusiasts, you may wish to subscribe to Hummingbird Hobnob, our Yahoo!-based discussion group. Also be sure to visit our award-winning Web site for Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project; on it you'll find almost anything you want to know about hummingbirds, including more information about Hummingbird Banding.

For much more information about hummingbirds, visit: |

|

Make direct donations on-line through

Network for Good: |

|

|

LIKE TO SHOP ON-LINE?

Donate a portion of your purchase price from 500+ top on-line stores via iGive: |

|

|

Use your PayPal account

to make direct donations: |

|

|

Back to Vagrant & Winter Hummingbird Banding Back to This Week at Hilton Pond Back to What's New? Current Weather Conditions at Hilton Pond Center |

|

post questions for The Piedmont Naturalist |

Join the |

Search Engine for |

|

|

By this time, however, the hummingbird was practically sitting on our elbow as we tried to rig the string, so we decided to just hold the trapdoor open 'twixt thumb and forefinger and--sure enough--after another couple of minutes the hummingbird flew into the trap to feed. With some amazement, we released our grip on the door and it slid shut six inches from our nose, safely snaring the hummer at 7:55 a.m. So much for the reliability of our brand-new high tech trapping device. (NOTE TO ELECTRICAL GURUS: If anyone knows for sure what might cause interference with a 75.610MHz receiver, please let us know via

By this time, however, the hummingbird was practically sitting on our elbow as we tried to rig the string, so we decided to just hold the trapdoor open 'twixt thumb and forefinger and--sure enough--after another couple of minutes the hummingbird flew into the trap to feed. With some amazement, we released our grip on the door and it slid shut six inches from our nose, safely snaring the hummer at 7:55 a.m. So much for the reliability of our brand-new high tech trapping device. (NOTE TO ELECTRICAL GURUS: If anyone knows for sure what might cause interference with a 75.610MHz receiver, please let us know via

Students at GLOBE-certified schools may submit winter hummingbird observations as part of Operation RubyThroat and GLOBE. Students can also correlate hummingbird observations with data on abiotic factors, including atmosphere, climate, hydrology, soils, land cover, and phenology. See the

Students at GLOBE-certified schools may submit winter hummingbird observations as part of Operation RubyThroat and GLOBE. Students can also correlate hummingbird observations with data on abiotic factors, including atmosphere, climate, hydrology, soils, land cover, and phenology. See the