|

|

|||

|

|

|

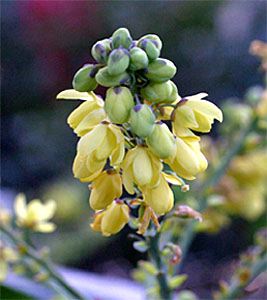

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Thanks to an E-mail from Ross Hawkins, president and founder of The Hummingbird Society, we learned on 13 January that a hummingbird was frequenting a yard in Charlotte NC (Mecklenburg County)--about 40 miles up the road from Hilton Pond Center. Carol Tomlinson, a former art teacher who lives in a nicely landscaped urban home near Queens College, was startled to see a hummer outside her window on 10 January--especially because it was bitterly cold and a mixture of snow and sleet was falling. The bird was hovering around and feeding from the quarter-inch yellow blossoms on Carol's Japanese Mahonia (Mahonia japonica), a frequently planted ornamental shrub with prickly, holly-like leaves that obviously blooms in the dead of winter (see photos below).

Flowers of "old-style" Japanese Mahonias are quite fragrant, so they must have some nectar that would provide carbohydrates for a wintering hummer, and the blossoms also attract tiny cold-tolerant insects that a hummingbird would consume as a source of much-needed fats and proteins. (NOTE: Some mahonia cultivars seem to lack both fragrance and nectar, so avoid them if you're planting to attract hummers. Oregon Grape, M. aquifolium, is a closely related native species from the Pacific Northwest that winter hummingbirds also like.)

Suspecting that tiny mahonia flowers might not provide enough sustenance for her hummingbird, Carol quickly brewed up some sugar water mix and put back up a feeder that she maintains all summer for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. Sure enough, the winter hummer quickly found the feeder and started making occasional visits as Carol searched the Internet for information and advice on what else she might do. Carol E-mailed Dr. Hawkins' who, in turn, forwarded us her note--after which we called and arranged to be at her place at dawn on 15 January.

We arrived in Charlotte at 7 a.m. and moved Carol's feeder into our portable hummingbird trap. Then we hung the whole apparatus on a shepherd's crook outside her study window and went inside with our wireless transmitter that, despite some recent quirks, we set up to trip the door on the trap.

It was quite apparent as we went outside to retrieve the bird that it had a green back and lots of rusty color at the base of its tail (above right), so we immediately suspected we had caught another female Rufous Hummingbird. In fact, when we carefully removed it from the trap, we saw a green forehead and a throat bearing a scattering of iridescent orange-red feathers--both characteristics of an adult female Rufous. There was always the possibility the bird could have been either a young male Rufous or even an Allen's Hummingbird--both of which are somewhat smaller than a female Rufous--but the bird's big wing measurement ruled out both these possibilities and clinched our original diagnosis. Carol Tomlinson's hummer had perfect, well-maintained plumage and weighed in at a very healthy 3.7g--a bit heavier than the typical female Rufous Hummingbird at mid-winter. Without doubt, this Charlotte bird was in top shape, so it must have been doing just fine on mahonia nectar, tiny bugs, and sugar water. After banding and photographing it, we released the bird and watched as it flew to a nearby treetop, undoubtedly to preen and eventually make a bee-line back to the feeder that Carol had so thoughtfully provided. At some point in the next couple of months, this bird is expected to head back to her breeding grounds in southern Alaska, western Canada, or the northwestern U.S., and maybe next year she'll decide to overwinter with most of the rest of her species in central Mexico. Thanks to Carol Tomlinson--and to Dr. Ross Hawkins--for providing an opportunity for us to return to Charlotte, where we banded a female Rufous Hummingbird 'way back in November 1991. That bird was the first of 51 winter hummers of four species we've banded in the Carolinas over the last 13 years and--who knows--just could have been the great-great-grandmother of the one we encountered at Carol Tomlinson's house in 2004.

Vital Statistics for

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

If you're interested in sharing your hummingbird observations and learning from other enthusiasts, you may wish to subscribe to Hummingbird Hobnob, our Yahoo!-based discussion group. Also be sure to visit our award-winning Web site for Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project; on it you'll find almost anything you want to know about hummingbirds, including more information about Hummingbird Banding.

For much more information about hummingbirds, visit: |

|

Make direct donations on-line through

Network for Good: |

|

|

LIKE TO SHOP ON-LINE?

Donate a portion of your purchase price from 500+ top on-line stores via iGive: |

|

|

Use your PayPal account

to make direct donations: |

|

|

Back to Vagrant & Winter Hummingbird Banding Back to This Week at Hilton Pond Back to What's New? Current Weather Conditions at Hilton Pond Center |

|

Join the |

|

post questions for The Piedmont Naturalist |

Join the |

Search Engine for |

|

|

. .

. .

Since Carol had seen her hummingbird only a few times over a five-day span, there was no guarantee the bird would even visit the feeder, so we pulled up a chair and settled in for what could be a long wait. Exuding confidence that the bird would appear, we gazed out the window and--quite amazingly--only had to wait about 45 minutes until it zipped into view, entered the trap without hesitation, perched on the feeder within, and started lapping up sugar water. We let the bird drink for about 15 seconds and then hit the release button that would close the sliding trapdoor behind the hummer. We're pleased to report that the remote device worked like a charm.

Since Carol had seen her hummingbird only a few times over a five-day span, there was no guarantee the bird would even visit the feeder, so we pulled up a chair and settled in for what could be a long wait. Exuding confidence that the bird would appear, we gazed out the window and--quite amazingly--only had to wait about 45 minutes until it zipped into view, entered the trap without hesitation, perched on the feeder within, and started lapping up sugar water. We let the bird drink for about 15 seconds and then hit the release button that would close the sliding trapdoor behind the hummer. We're pleased to report that the remote device worked like a charm.

Students at GLOBE-certified schools may submit winter hummingbird observations as part of Operation RubyThroat and GLOBE. Students can also correlate hummingbird observations with data on abiotic factors, including atmosphere, climate, hydrology, soils, land cover, and phenology. See the

Students at GLOBE-certified schools may submit winter hummingbird observations as part of Operation RubyThroat and GLOBE. Students can also correlate hummingbird observations with data on abiotic factors, including atmosphere, climate, hydrology, soils, land cover, and phenology. See the