|

|

|||

We've long had deep interest in West Virginia natural history, having been a delegate to that state's National Youth Science Camp long ago and working on staff thereafter for many summers. Through the years during science camp sessions in Pocahontas County we banded quite a few species--including more than a hundred Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--and we still subscribe to the WV-BIRD listserv to keep abreast of avian activities in the Mountain State.

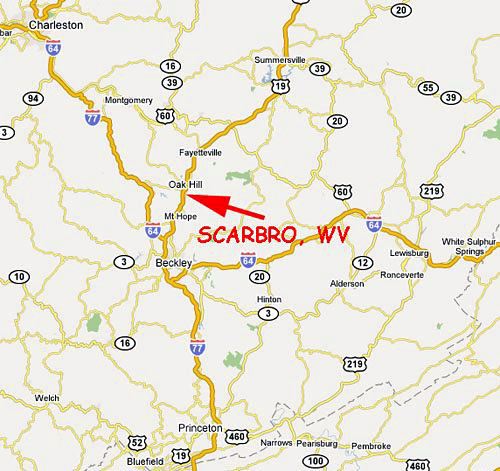

We left Hilton Pond Center mid-afternoon on 14 December and arrived about four hours later in Oak Hill WV, 250 miles to the north up I-77 and U.S. 19. There, Dave and Lynn Pollard--also old friends and two of the New River Festival organizers--offered us lodging. After some great conversation, we all retired to our bedrooms in anticipation of the next day's events. Needless to say, 5:30 a.m. came early, but we roused up and headed back down U.S. 19 toward a gas station where we rendezvoused with Mindy and Allen Waldron and Alma Lowry, who came from nearby Beckley. The roads into the Scarbro were narrow, winding, and unfamiliar, so we were glad to have another car lead us to the little coal mining village in pre-dawn darkness. As planned, we got to the Soward residence at about 6:15 a.m. on 15 December, met Bud and Sue (below right)--plus avid birder Wendell Argabrite who had driven over from Huntington--and checked out Bud's feeding operation. We removed the heat lamp and transferred Bud's feeder into our portable hummingbird trap, which we then hung back up on the Soward's side porch. By 6:25 a.m. the small crowd of hummingbird enthusiasts went into the kitchen to wait for first light and the anticipated arrival of a vagrant hummer . . . or two . . . or more. As the clocked ticked onward the sky brightened somewhat, but Bud--who had been keeping careful notes on hummingbird feeder visits--said he didn't expect any business until 7:28 a.m. After almost an hour of conversation, 7:25 a.m. approached, so we started teasing Bud about his prediction. At 7:26 a.m. we heard the arrival of another car--out of which stepped Lynn Pollard, just in time and with binoculars at the ready. Lucky for her, at 7:27 a.m. a hummingbird appeared, spent about minute or so investigating the trap, and at 7:28 a.m. flew on in. We quickly flipped the switch that remotely released a sliding door on the trap and we had ourselves a VERY punctual winter hummingbird.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center As we carefully removed the hummer from the trap it was immediately obvious this was NOT the individual Allen had photographed and Mindy had reported the previous week at the Sowards. The bird in Allen's photo (top of page) was quite rusty on its back and head, while the one we had just caught was uniformly green-backed (below).

Based on all the rusty color at the base of its tail, this new capture was obviously a Selasphorus hummingbird--either a Rufous or an Allen's. It seemed a tad small, so we suspected it, too, was a young male--especially since its metallic gorget feathers were scattered on the throat rather than in a cohesive spot that typically is found in female Rufous and Allen's.

To verify the species and sex of Bud's hummingbird we took a series of measurements, including wing chord, culmen, and tail, (see chart below). Allen's Hummingbirds are somewhat smaller than Rufous, and in female and juvenile male Allen's the outer tail feather (rectrix) is extremely narrow. In both Rufous and Allen's females are as much as 25% larger than males of any age.

We could easily rule out Allen's Hummingbird--the Soward's bird had a wide outer rectrix--but conclusively determining its sex was a little tougher because all its measurements were at the upper limit for young males and even encroached on the range for females. However, since the tail feathers did not have noticeably nippled (tapered) tips (below left), We banded the Scarbro hummer on its left leg (as we do with all males) and checked it for stored fat in the wishbone or furcular region (there was only a trace). We also spread the bird's wing to look for molt (below). What we found was that the outermost primary flight feathers (numbers 7-10) were somewhat faded and "old"--i.e., they were what the bird hatched out with--but that primaries number 1-6 were fresh and somewhat darker, indicating they were newly replaced. The darkest feathers in the photo below are recently molted primary coverts that cover and streamline the bases of the primaries. Having derived as much information from this bird as we reasonably could we took it outside for a series of documentary photographs in early morning light. Eventually we placed the winter vagrant Rufous Hummingbird on Bud's palm--where the newly banded #Y14574 sat several seconds before exploding skyward toward a nearby tall tree. No other hummingbirds showed up while we were Scarbro that day.

Before departing, we thanked Bud and Sue Soward for allowing us to visit early on a Saturday morning, acknowledged Mindy and Allen Waldron for alerting us to the vagrant hummingbird, and expressed appreciation to Lynn Pollard for the previous night's lodging. After a series of goodbye hugs, we were off for a breakfast meeting at the highly popular Cathedral Cafe in downtown Fayetteville, and then it was back southward on I-77 toward Hilton Pond Center. Vital Statistics for POSTSCRIPT #1: Mindy Waldron tells us Bud Soward reports he did not see the banded hummingbird the rest of the day on 15 December, but that it did return to feed the following morning and at least once more that day. We wonder whether Bud will get any more winter hummingbirds this year or next, and we're curious (as always) how a vagrant Rufous Hummingbird--which breeds in southern Alaska, western Canada, and the northwestern U.S.--happens to be in central West Virginia in December when nearly all its conspecifics are spending the winter in balmy central Mexico. POSTSCRIPT #2: We encourage all West Virginia birders to keep up at least one hummingbird feeder past the traditional take-down date of Labor Day. If you get a winter hummer, please report it to WV-BIRD and/or Hilton Pond Center via E-mail at RESEARCH. West Virginia now has four hummingbird species confirmed for the state list: Ruby-throated (which breeds there every year and departs each autumn), plus Rufous, Black-chinned (first record in Nov 2006), and a far-out-of-range Green Violet-ear. Visit Hilton Pond Center's Web site for info on Winter Hummingbird Feeding Hints & Research. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

If you're interested in sharing your hummingbird observations and learning from other enthusiasts, you may wish to subscribe to Hummingbird Hobnob, our Yahoo!-based discussion group. Also be sure to visit our award-winning Web site for Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project; on it you'll find almost anything you want to know about hummingbirds, including more information about Hummingbird Banding. You may also wish to read more about Winter Hummingbirds that are showing up in the eastern U.S.

For much more information about hummingbirds, visit: |

|

Make direct donations on-line through

Network for Good: |

|

|

LIKE TO SHOP ON-LINE?

Donate a portion of your purchase price from 500+ top on-line stores via iGive: |

|

|

Use your PayPal account

to make direct donations: |

|

|

Back to Vagrant & Winter Hummingbird Banding Back to This Week at Hilton Pond Back to What's New? Current Weather Conditions at Hilton Pond Center |

|

post questions for The Piedmont Naturalist |

Join the |

Search Engine for |

|

|

Understandably, we were very interested when old friends Mindy and Allen Waldron posted a note on 9 December 2006 that at least one and possibly several winter hummingbirds were coming to a feeder in Scarbro in Fayette County WV. (This area is home of New River Gorge and the

Understandably, we were very interested when old friends Mindy and Allen Waldron posted a note on 9 December 2006 that at least one and possibly several winter hummingbirds were coming to a feeder in Scarbro in Fayette County WV. (This area is home of New River Gorge and the

He had one feeder with a heat lamp attached to the base to keep it from freezing; this was the one used most often by his winter hummingbird(s). Bud mentioned he had been using a standard 1:4 sugar water mix, but when he tried to substitute with store-bought mixes the hummingbird(s) actually disappeared--to which we replied that he shouldn't mess with success. Bud also said he thought he could have had as many as five different hummers this winter, based on apparent variations in coloration and behavior.

He had one feeder with a heat lamp attached to the base to keep it from freezing; this was the one used most often by his winter hummingbird(s). Bud mentioned he had been using a standard 1:4 sugar water mix, but when he tried to substitute with store-bought mixes the hummingbird(s) actually disappeared--to which we replied that he shouldn't mess with success. Bud also said he thought he could have had as many as five different hummers this winter, based on apparent variations in coloration and behavior.

and because of the scattering of gorget feathers, we concluded Bud's bird was a "hatch year" male born sometime in 2006--although there is a distinct possibility the bird is a female. (Sometimes banders simply have to say they can't be 100% positive on the sex of a "borderline" bird.) The presence of etchings or corrugations along 50% of the bird's upper bill reinforced it was a "young" bird; in older hummers the upper bills are almost completely smooth.

and because of the scattering of gorget feathers, we concluded Bud's bird was a "hatch year" male born sometime in 2006--although there is a distinct possibility the bird is a female. (Sometimes banders simply have to say they can't be 100% positive on the sex of a "borderline" bird.) The presence of etchings or corrugations along 50% of the bird's upper bill reinforced it was a "young" bird; in older hummers the upper bills are almost completely smooth.

Students at GLOBE-certified schools may submit winter hummingbird observations as part of Operation RubyThroat and GLOBE. Students can also correlate hummingbird observations with data on abiotic factors, including atmosphere, climate, hydrology, soils, land cover, and phenology. See the

Students at GLOBE-certified schools may submit winter hummingbird observations as part of Operation RubyThroat and GLOBE. Students can also correlate hummingbird observations with data on abiotic factors, including atmosphere, climate, hydrology, soils, land cover, and phenology. See the