|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

|

|

|

A SLOW BUT INTERESTING START As the ball dropped New Year's Eve and the sun came up on 2012, we began our 31st year of education, research, and conservation activities through Hilton Pond Center with a celebratory walk around the property and the banding of three Yellow-rumped Warblers. These "butterbutts" and a small cadre of House Finches are about the only birds in evidence so far this winter at the Center--a far cry from last year's invasion of Pine Siskins and other cold weather birds. EVERYTHING is down for us during what is traditionally our most productive banding period. We're hosting almost no White-throated Sparrows or Dark-eyed Juncos; Purple Finches and siskins are absent; and even resident species like Northern Cardinals and Eastern Towhees are scarce. (Carolina Chickadees and Eastern Tufted Titmice are present, but all are already banded.) At week's end we'd caught only 14 new birds from three species: Those three yellow-rumps, ten House Finches, and an elegantly attired Cedar Waxwing we hand-captured (below) after it was mildly stunned during a window strike. With such meager pickings among local birds, we were eager to accept an invitation to journey from York to Atlanta for a visit with Mary Kimberly and Gavin MacDonald, a couple of Operation RubyThroat "groupies" who had been with us on hummingbird expeditions to Guanacaste Province in Costa Rica and also to Belize and Guatemala.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We headed down I-85 on the afternoon of 6 January, having already planned an overnight stop two hours away in Greenville at the home of a relative. It wasn't that we couldn't make the four-hour drive to Atlanta at one sitting. No, we had an ulterior motive, and we also have a confession to make. Over the Christmas holidays we were at the same relative's house and got word of a possible Rufous Hummingbird nearby at the Anderson SC residence of Bonnie and Dick Arielly. Master Gardener Bonnie has been feeding summer hummers at Anderson since the late 1990's but never had a winter one before. She mentioned this bird to a neighbor, Mike Vandiver, a Methodist minister who had gone to Wofford College with our good friend and fellow naturalist Rudy Mancke, star of "NatureScene." Mike suggested Bonnie alert Rudy--who knew of our hummingbird work through Hilton Pond Center--and Rudy in turn suggested Bonnie contact us, which she did. We made arrangements with Bonnie about coming to see her winter hummer and awoke early on 26 December for a 45-minute jaunt to the Arielly home on Lake Hartwell. The hummingbird eventually did enter our trap but was so fast it got out before the door slid shut to snare it--not once but FOUR times! In more than 70 previous attempts to trap winter vagrant hummingbirds we'd struck out only once, and this was the first time we'd ever had a hummer slip away so many times. After several unsuccessful hours and humbled by this setback, we vowed to Bonnie and Dick we'd stop to try again during the first week in January on our way to Atlanta.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center By 5:40 a.m. on 6 January we were driving back down the now-familiar route to the Arielly's. It was still dark as we arrived just before 6:30 a.m. so we quickly set up our remotely triggered electronic trap with sliding door and placed the sugar water feeder inside. (We should mention we had made one change to the apparatus since our last visit: We added wire to reduce the door opening by about 30% to make it harder for any especially aerobatic hummers to escape.) In addition to hosts Bonnie and Dick, the gallery in attendance now included Mike Vandiver and wife Donna, neighbor Bill Gurley, and long-time supporter Susan Hilton. Following introductions all around, we sat back to see when--and IF--the elusive hummer would show. About an hour later as morning sunlight crept across the cove a hummingbird zipped by, looked at our trap, and quickly disappeared. The bird returned briefly several times over the next 20 minutes and even flew into the set-up (above), never staying long enough. Finally, at 7:50 a.m. the hummer warily entered the trap and sat on a perch to feed; it took us only a fraction of a second to flick the remote switch that safely captured the object of our attention. After carefully removing the hummer from the trap we gave it a quick look to be sure it was okay and took it indoors for banding.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We immediately saw that this bird was NOT a Ruby-throated Hummingbird. It had a few metallic orange-red feathers on its throat, and its flanks and the base of its tail were rusty-colored--a good sign this was one of the Selasphorus hummingbirds from western North America. Because the rectrices (tail feathers) were NOT extremely narrow, we knew it couldn't be an Allen's Hummingbird (S. sasin), so that meant it was a Rufous Hummingbird (S. rufus)--by far the most likely of several western vagrant hummers that wander eastward in winter.

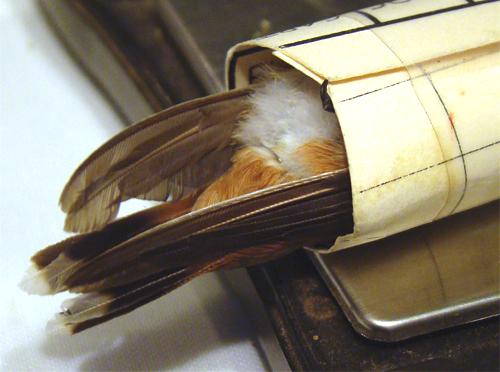

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We gently slid the hummer in a paper tube (above) and weighed it (3.41 grams--about 3/5ths the weight of a nickel) before taking other measurements to see if we could determine the bird's sex. Unlike Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in which only males have iridescent throat feathers, in Rufous Hummingbirds females also exhibit this trait.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We suspected the bird was a female, which we confirmed by the length of its wing chord and upper bill ridge (culmen). The former was 45.17mm--noticeably bigger than the range of 38-43mm for males--and the culmen was 18mm (at the upper limit for a male rufous and thus more likely for the larger female).

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We also looked at the hummer's face (above), which was rather plain and without distinct markings. This and the measurements led us to conclude the bird was indeed an immature female Rufous Hummingbird that Bonnie Arielly spontaneously and inexplicably nicknamed "Raphaella."

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Of special interest on Raphaella was the condition of her tail (above): The outer white-tipped rectrices were worn, and the inner two feather pairs were short and just coming in. Tail molt typically begins with the central feathers and proceeds toward outer pairs, so it appeared this Rufous Hummingbird had begun her tail molt--a good thing to do if a long-distance migration is to occur sometime in the next month or two. It's always good to have fresh tail feathers before embarking on an extended journey of 3,000 miles or so. Interestingly, Raphaella also was bringing in some new body plumage but there was no sign of molt in her all-important wing feathers.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center With measurements complete, we banded the hummer on its right leg with a tiny aluminum bracelet inscribed " Y14669" and removed Raphaella from the tube. Placing her bill in the open port of the hummingbird feeder we were pleased to see the bird drank freely of sugar water (above)-- All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Having achieved our banding goals at the Arielly house, we thanked Bonnie and Dick for their cooperation and generosity and re-boarded our van for the remainder of our voyage to the Atlanta home of Mary Kimberly and Gavin MacDonald (shown above wearing two very nice T-shirts after a long day in the field in Costa Rica). Again, this couple participated in three of our Neotropical hummingbird expeditions and had become good friends; we were happy to see them again for the first time since our get-together in Guatemala in February 2011. They showed us around their pleasant home and yard, complete with nest boxes and numerous bird feeders--one containing suet being consumed by Eastern Bluebirds, Ruby-crowed Kinglets, and Pine Warblers.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center As we scanned this birdy backyard scene in Atlanta we spotted a female Northern Flicker investigating a box that Mary said was occupied in previous years by a nesting pair of Eastern Screech-Owls. When we looked at the flicker through binoculars we immediately noticed something unusual: The bird's mandibles were severely crossed (above). We rarely have seen abnormally crossed bills in other species--including a House Finch at Hilton Pond Center--but it was startling this could occur in an adult woodpecker. After all, a woodpecker's long, straight bill is critical for removing prey items from wood and for excavating nest holes in old snags. It's a wonder a Northern Flicker could survive for any length of time with such a distorted bill--until we note that flickers spend a lot of time feeding on the ground where they consume ants and other terrestrial arthropods that might be grabbed even with crossed mandibles. (Flickers also eat winter berries and seeds.) That Mary and Gavin had erected a big hollow box also worked in the flicker's favor; the bird no longer had to concern herself with making her own nest cavity. We don't know what might have led to an aberrant bill in this woodpecker, but possible causes include disease, injury, developmental or genetic abnormality, and chemical pollutants. After contemplating this Northern Flicker with an unusual bill it was off to lunch at a local eatery--the barbecue ribs were amazing--and then to explore our main reason for being in Atlanta: Mary and Gavin had thought about us when they visited the High Museum of art for an exhibit by bird sculptor Grainger McKoy.

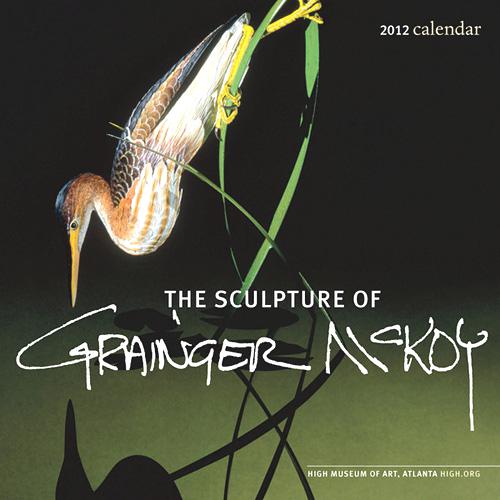

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our Atlanta buddies were so struck by Grainger McKoy's sculptures--magnificent wooden bird carvings painted in true colors and mounted in lifelike positions--that they sent us a exhibit calendar (above, with Least Bittern sculpture) and a note inviting us to the last weekend of the show. In a serendipitous situation, Mr. McKoy himself was on hand that day and we got to do a gallery crawl with him as he explained his sculptures and how he does what he does.

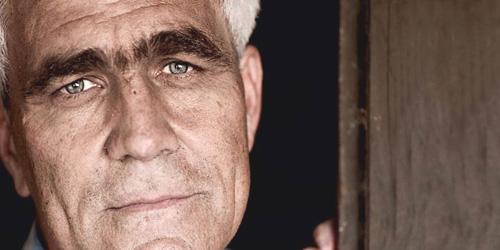

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Grainger McKoy (above) was born in 1947 in Wilmington NC and starting carving as a youngster when his parents moved the family to a log cabin near Sumter SC. He still has his first rendering--

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center What Maggioni and McKoy did was carve and paint birds that were scrupulously accurate (male American Kestrel, above)--down to having the right number of feathers--and that were rendered in natural poses quite unlike the flat-bottomed duck decoys that had dominated bird carving for centuries. These two Southern carvers had invented a technique that made birds look so natural they seemed alive.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Part of this liveliness was made possible when McKoy leaned on his early training in architecture and figured out how to use spring steel to join wooden birds together in lifelike groupings, as with a seven-foot-high flock of Sanderlings (above). Exhibit-goers--including the ones this week in Atlanta--are always stunned by the beauty of McKoy's carving and painting, but they're just as intrigued about how he's able to create a tableau in which gravity-defying birds truly look like they're flying. "In the old days I carved decoys to fool birds," McKoy told us. "These days I carve birds to fool people."

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center For the past 40 years Grainger McKoy has honed his talents to become the world's pre-eminent bird sculptor. He has exhibited in art museums from New York to Palm Beach, his works are sought after by private collectors and museums alike, and he supports his art in part through the sale of his line of bird jewelry. He works strictly on commission and carves a sculpture of a bird HE wants to depict, not necessarily one the patron wants. McKoy said he'd never do a loon because he doesn't "know" loons; he only carves species he knows--which is why Northern Bobwhite quail he hunts are often the subject of his work. He has made a few exceptions to his rule, however, as when he carved and painted a life-sized Ivory-billed Woodpecker (above). McKoy couldn't have personally observed this now-extinct bird, so he did the next-best thing by observing closely related Pileated Woodpeckers and spending days studying and sketching hundred-plus-year-old specimens of ivory-bills in The Charleston Museum.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center McKoy followed this same strategy with his 88-inch-tall group sculpture of the Carolina Parakeet (above)--another native Carolina bird that's been gone for nearly a century--by observing live Conure parrots as he created the sculpture above. How incredible that an artist could be so gifted as to be able to show us how two extinct bird species would look if they were still alive and flying about in today's landscape.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Despite our slow birding and banding start for 2012 at Hilton Pond Center we did get to catch that Rufous Hummingbird this week at the Arielly's house in Anderson SC and then go on to Atlanta to be with old friends Mary and Gavin. That was all very fine, but getting to see Grainger McKoy's incredible bird art AND talk with him personally (above) was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity we won't soon forget. We hope the rest of 2012--our 31st year at Hilton Pond--is even half as good. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center |

|---|

The Piedmont Naturalist, Volume 1 (1986)--long out-of-print--has been re-published by author Bill Hilton Jr. as an e-Book downloadable to read on your iPad, iPhone, Nook, Kindle, or desktop computer. Click on the image at left for information about ordering. All proceeds benefit education, research, and conservation work of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. The Piedmont Naturalist, Volume 1 (1986)--long out-of-print--has been re-published by author Bill Hilton Jr. as an e-Book downloadable to read on your iPad, iPhone, Nook, Kindle, or desktop computer. Click on the image at left for information about ordering. All proceeds benefit education, research, and conservation work of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. |

|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

If you Twitter, please refer

"This Week at Hilton Pond" to followers by clicking on this button: Tweet Follow us on Twitter: @hiltonpond |

Comments or questions about this week's installment? Send an E-mail to INFO. (Be sure to scroll down for a tally of birds banded/recaptured during the period, plus other nature notes.) |

Click on image at right for live Web cam of Hilton Pond,

plus daily weather summary

Transmission of weather data from Hilton Pond Center via WeatherSnoop for Mac.

|

--SEARCH OUR SITE-- For a free on-line subscription to "This Week at Hilton Pond," send us an |

|

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond." Please see Support if you'd like to make a gift of your own.

|

If you enjoy "This Week at Hilton Pond," please help support Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. It's painless, and YOU can make a difference! (Just CLICK on a logo below or send a check if you like; see Support for address.) |

|

Make credit card donations on-line via Network for Good: |

|

Use your PayPal account to make direct donations: |

|

If you like shopping on-line please become a member of iGive, through which 950+ on-line stores from Amazon to Lands' End and even iTunes donate a percentage of your purchase price to support Hilton Pond Center.  Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase through them earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause!Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase through them earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause!Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. |

|

a pretty good sign she wasn't under any kind of real stress. Then, after finishing our usual series of photos to document the hummer's appearance, we placed Raphaella in Bonnie Arielly's open palm. The bird was in no hurry to depart and allowed several more photos before we nudged her with a finger and she zipped off to a nearby tree. We pondered when this "wayward" hummer might be departing South Carolina for her breeding grounds in southern Alaska, western Canada or the northwestern U.S. and secured a promise from Ariellys they'd let us know the bird's departure date.

a pretty good sign she wasn't under any kind of real stress. Then, after finishing our usual series of photos to document the hummer's appearance, we placed Raphaella in Bonnie Arielly's open palm. The bird was in no hurry to depart and allowed several more photos before we nudged her with a finger and she zipped off to a nearby tree. We pondered when this "wayward" hummer might be departing South Carolina for her breeding grounds in southern Alaska, western Canada or the northwestern U.S. and secured a promise from Ariellys they'd let us know the bird's departure date.

a shorebird

a shorebird

Oct 15 to Mar 15:

Oct 15 to Mar 15: