|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

|

|

|

WINTER HUMMINGBIRDS IN THE U.S. In the Carolinas since 1991 we've banded 73 so-called "vagrant" hummers--i.e., NOT Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. The vast majority of these bandings have been Rufous Hummingbirds--a species that breeds in southern Alaska, western Canada, and the northwestern U.S. and historically wintered primarily in central Mexico. We've also captured four other vagrant Carolina species, including three Calliope Hummingbirds, one Black-chinned Hummingbird, and the only Broad-billed and Buff-bellied Hummingbirds ever banded in the Palmetto State. Even though we've banded all these "winter vagrant" hummers, we'd never handled a Ruby-throated Hummingbird after 18 October or before 27 March--except, of course, for those we encounter during our annual mid-winter Operation RubyThroat expeditions to such Central American locales as Aloe Vera fields in Costa Rica (immature male RTHU, below left).

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Ruby-throated Hummingbirds have been documented since about 1970 as wintering in Gulf Coast states, perhaps before that in southern areas of Florida and Texas. More recently a smattering of hardy RTHU have even appeared--and in some cases have been banded by other investigators--during winter months all along the Carolinas Coastal Plain from Kiawah Island north to Myrtle Beach and on to the Virginia border. Thus, we weren't surprised back in December when a fellow science educator and environmentalist reported she was hosting a half-dozen or more Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in coastal Buxton NC and would be happy to host us if we'd come out to band them. We'd never been to Hatteras Island on the Outer Banks (see satellite image above) and jumped at the chance to handle some wintering maritime ruby-throats in advance of our upcoming excursion to Costa Rica.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center We (bander Bill Hilton Jr. and wife Susan) headed for the coast mid-afternoon on Friday the 13th, grateful we could stop in Durham NC to spend the night at the home of our favorite Aunt Carmen. (Driving the whole 475 miles from York to Buxton after such a late departure would have been too exhausting.) Following a nice visit with Carmen and cousins Scott and Mark in Durham we resumed our travels on 14 January, knowing we were still nearly five hours from our destination. We found the trip through the North Carolina Sandhills quite a bit different from driving across the Carolina Piedmont. Instead of rolling hills and curvy roads everything is very flat, very straight, and very isolated. We passed occasional small towns and many huge farms that grow everything from sod to soybeans, and as we got closer to the coast entered Alligator National Refuge--an expanse of Lowcountry swamps and pinelands that are stomping grounds for a small population of endangered Red Wolves. Signs that warned "Do Not Feed Bears Along the Road" were a bit of a surprise, but understandable considering the wilderness that surrounded eastbound U.S. 64.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center We crossed over the Alligator River--wider than the mighty Mississippi--onto Roanoke Island of Virginia Dare fame and came to the town of Manteo before turning south onto N.C. 12. At last we were on a barrier island that is part of the Outer Banks--an ever-shifting sliver of land that at several points is only a few hundred yards wide (sometimes less after hurricanes). Then it was past Pea Island to the tri-cities of Rodanthe, Waves, and Salvo until we came to Cape Hatteras National Seashore, breeding grounds for federally protected species such as Piping Plovers, Seabeach Amaranth, and Loggerhead Sea Turtles. About 30 minutes further south we finally could see the famous 1870s Cape Hatteras Lighthouse (above right)--a 208-foot-tall black and white brick tower that in 1999 had been moved a half-mile inland to protect it from toppling into the encroaching ocean. With this famous structure in view we knew we were approaching the little fishing town of Buxton, home of our educator friend and her husband and their thriving winter population of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our van hit the 475-mile mark as we rolled into our friend's driveway at about 1:30 p.m. on 14 January. She and her hubby live back in the woods about halfway between the Atlantic Ocean and Pamlico Sound within a sparsely settled subdivision outside refuge boundaries. The house has a small open lawn surrounded by dense scrub and trees, plus quite a few hummingbird nectar plants not blooming at this time of year. Interestingly, the homeowners maintain five-foot-tall nectar-bearing hibiscus plants in large pots they roll out for use by hummers on mild winter days. There also was a collection of hummingbird feeders hanging from limbs or shepherd crooks or stuck to windows with suction cups, but the yard's most noticeable attribute was several contraptions from which emanated black or bright orange extension cords that ran to electrical outlets. Each device was a custom-made "hummingbird spa" (above) consisting of a plastic planter under which a heat lamp shined continuously on a Perky-Pet feeder with perches. Even during an Outer Banks snowstorm last winter, the lamps reportedly kept sugar water from freezing and allowed hungry hummers to feed at will.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our host is an accomplished photographer--she and her husband are also meticulous wildlife observers--and for several weeks she had been sending me annotated photos of her winter hummers, which she believed were all Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, Archilochus colubris. With a long lens she was able to get images that showed distinctive differences among the birds, individuals so recognizable they earned nicknames based in part on which feeders each defended. One hummer--"Office Female"--dominated the study window, "Hill Bird" patrolled a low sand dune in front of the house, and a couple of similarly named males hung out elsewhere. Although most of the hummingbirds appeared to be very territorial, occasionally two would feed together (above).

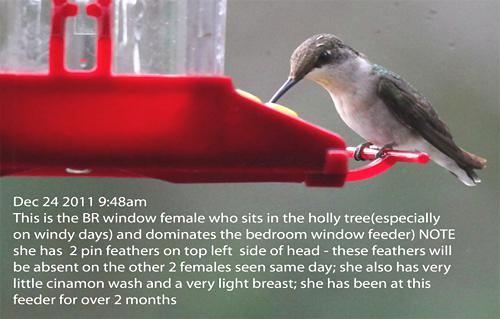

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center All the apparent females were white-throated but had varying amounts of buff on their flanks and one--"Bedroom Bird" (above) even had a couple of long-lasting pinfeathers that made her easy to identify. There had been a couple of adult males around earlier in the winter but they had disappeared, leaving only immatures with incomplete gorgets. These were easy to pick out and went by "Triple Spot" (below left), "Little Spot," and "Dotted Line," nicknames derived from the number and position of their iridescent red throat markings. During a quick lunch we spotted the first fast-flying visitor to this Buxton backyard oasis--an apparent female Ruby-throated Hummingbird--so after unloading luggage and equipment we quickly set up our portable hummer trap in place of one of the "spas." The first bird--or perhaps a different one We say "appeared to be" a ruby-throat because there is greater probability a winter hummer in the Carolinas will be one of those OTHER vagrant species, such as Rufous Hummingbirds or even female Black-chinned Hummingbirds, Archilochus alexandrii, that look almost exactly like female Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, A. colubris. (This shouldn't be a surprise because black-chins and ruby-throats are so closely related they're in the same genus.) Black-chinned Hummingbirds, however, tend to have somewhat longer, slightly decurved bills and flick their tails a lot when they feed--characteristics our host hadn't mentioned and that we hadn't seen thus far.

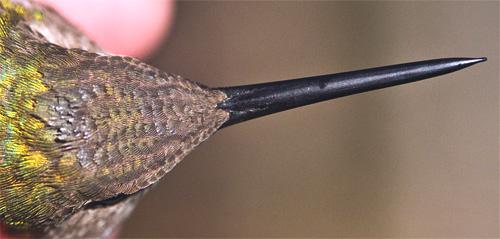

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center As we carefully removed the just-caught hummer from our trap we looked for and didn't see a rusty base to the tail that would have indicated Rufous or Allen's Hummingbird--two species in which females only superficially resemble ruby-throats. The bird was too big for a Calliope and too small for a Buff-bellied, and there were no other field marks that indicated it wasn't an Archilochus. Thus, we had to decide between Black-chinned Hummingbird and Ruby-throated Hummingbird, a task made easier by examining the bird's outer (#10) primary. In black-chins this feather is club-shaped (above left) with more webbing along the lead edge, while in ruby-throats the tip is straighter and more pointed (above right). The latter was true of our bird-in-hand, so we were confident this was indeed a Ruby-throated Hummingbird. We then confirmed it was a female because it lacked streaking or red feathers on its throat (see photo just below) and, more conclusively, because the tip of its #6 primary was rounded and untapered (not shown). In RTHU males of any age this #6 feather is heavily tapered to a dagger-like point.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center After concluding our first capture was a female Ruby-throated Hummingbird (AKA "Office Bird"), we took our standard measurements--weight, wing chord, tail, and culmen (top ridge of the upper mandible)--and applied a band inscribed #Y14670. Typical midsummer females at Hilton Pond Center tip the scales at about 3.5-4.0 grams, so at 4.09g this Buxton bird was surely getting her fill of sugar water and acquiring requisite fat and protein from small insects such as mosquitoes, gnats, and aphids. Even in the dead of winter on the Outer Banks such tiny arthropods are around in sufficient numbers to satisfy the needs of hungry hummers.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center We were especially interested to learn the status of wing and tail molt in this newly banded hummer. When ruby-throats depart Canada and the U.S. in autumn, they almost never show signs of bringing in new flight feathers. After all, if you're planning a long-distance migration of up to 2,000 miles to the Neotropics, the last thing you want is an incomplete wing or tail. Instead, RTHU acquire a whole new set of flight feathers on the wintering grounds--a process we've paid close attention to when we band this species in Central America. By late January, nearly all ruby-throats down there have begun acquiring new flight feathers, and by mid-February most have completely new wings and tails--just in time to begin a return trip north. As we expected, our first capture was still bearing an old tail with worn tips, and her wing feathers had central shafts (above) that were all brown and faded--not black. These definitely were not newly formed and would be replaced in coming weeks or months.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center As we finished processing the first hummer our host alerted us at 2:50 p.m. a second bird had entered the trap and settled down on a perch to drink. Again we flicked the electronic switch, and again we'd caught another winter Ruby-throated Hummingbird. As soon as we had this individual in-hand we knew who it was: The "Bedroom Window" female with two pinfeathers in her crown (above). Individual hummingbird feathers usually mature in a week or less, so these two feathers still in sheath may have been an example of "arrested development" in which the molt process starts but stops because of external factors--perhaps cold temperatures. It will be interesting to hear from the homeowner if the sheaths disappear before spring. At 3.41g this second bird was a bit lighter than her predecessor but certainly within range for a healthy female hummingbird. She received band #Y14689 and was on her way as soon as we completed our typical procedure of hand-feeding her a little bonus sugar water.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Shortly before 3:30 p.m. yet another ruby-throat investigated our trap and was snared in short order. This bird had a clear white throat and a rounded #6 primary--assuring she was a female--but her most noticeable attribute was a very brown head (above). Although we suspect based on our studies in Central America that a non-green crown and forehead on a mid-winter female Ruby-throated Hummingbird would indicate she's an immature, we've not been able to conclusively prove this to be true. On the other hand, summer females can be aged by looking at tiny bill etchings--young birds have more of these--but we've found this characteristic to be less reliable as early as four months or so after the hummer fledges. As the shadows grew long over Hatteras Island, we decided to allow the local "swarm" of coastal ruby-throats a chance to feed before darkness fell, so we shut down our trapping operation by 4:30 p.m.--fully aware there were at least a couple other hummers we had observed but not captured. Among those were two immature males with incomplete gorgets that would have to wait until the morrow to receive one of our little aluminum bands. Satisfied with our half-day of banding mid-winter ruby-throats, we sat down for an enjoyable supper of homemade pizza and calzones and an invigorating, far-ranging conversation about birds and science education that went well into the wee hours.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center We can't say we awoke at dawn on 15 January, but we did get up early enough to not feel guilty about our late-night discussion. After a quick breakfast we again erected our portable trap and sat back in indoor comfort to see what was happening this day with cold-weather hummingbirds on the Outer Banks. In a matter of minutes (8:20 a.m.) another ruby-throat flew inside our apparatus and we knew almost instantly by his two central red gorget feathers (above) this was "Little Spot." He was our first male Ruby-throated Hummingbird captured at Buxton and was noticeably smaller than those three females caught the previous day, with shorter culmen and wing chord measures and a weight of 3.11g. (Male ruby-throats meaurements are typically about 20-25% less than those in females.) He received band #Y14657 and--giving ample evidence he suffered no stress or trauma from being captured, measured, banded, or otherwise handled--he re-entered the trap at least four times during the day. Thus, he became one of those birds we refer to as "trap junkies."

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center We'd barely finished processing the immature male when at 8:30 a.m. we had our fifth capture (above)--one more female Ruby-throated Hummingbird. This bird (banded as #Y14618) was another of those individuals with a metallic green back but a brown forehead that may be indicative of immaturity. We also noted heavy wear in the white tips of her outer rectrices (tail feathers)--a common occurrence in long-distance migrants because white plumage lacks melanin pigment that helps provide structural strength. This bird weighed 3.06g.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Shortly before noon we caught our sixth winter ruby-throat at Buxton, a female that weighed 3.18g. She became #Y14619. At first glance it seemed this bird had faint markings high on her otherwise clear throat. In-hand we checked this out through our macro lens that initially made it look as if she had some sort of iridescence. However, a really up-close view (above) indicated not any pigment or structural color but a small deposit of yellow pollen grains. There's nothing remarkable about seeing a Ruby-throated Hummingbird bearing pollen, of course, except when one remembers we caught this bird in the dead of winter when flowering plants are exceedingly scarce. With a microscope we might have been able to determine the pollen's source, but without such optics we could only speculate. Perhaps the sticky pollen was left over from a few days previous when the homeowner had rolled out her collection of flowering hibiscus. By late morning things had really slowed down at our friend's cold weather hummingbird oasis, but we had another option for continuing our weekend work on the Outer Banks. In the midst of banding these out-of-season ruby-throats we got word that two other Buxton homes about a mile away also had hummingbirds at feeders, so we loaded the portable trap and banding equipment into our van and took a short drive. Sure enough, as we arrived and climbed the stairs to a second-floor balcony overlooking a freshwater swampy area, we saw a hummingbird flit toward a saucer-style feeder loaded with artificial nectar. We quickly set up our automatic trap--a task made a bit easier because the feeder wasn't heated--and went inside where a small crowd of people had assembled to watch the operation. We weren't about to disappoint the group and by 1:55 p.m. captured one more midwinter female Ruby-throated Hummingbird. At this point we went into teaching mode, concentrating on the newly captured hummer and how we age, sex, measure, and band these miniscule birds. Thus, we took no photos, leaving it to our host to lean over and snap exposures as we taught. This first bird at the alternate site weighed 3.58g and received band #Y14620.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center At 2:35 p.m. another female RTHU entered the trap and even while we carefully removed her we realized we had a bird with interesting flight feathers. As we examined the hummer with the group our host snapped away with her digital camera and one of her images (above) revealed what was curious about the bird's wing: She was in the middle of molting her primary flight feathers. Primaries #6-10 were old and faded, #5 was missing, #4 was about one-third grown, and #1-3 were dark and new. We've encountered this molt status many times on Ruby-throated Hummingbirds we band in the Neotropics January through early March but it was something we had not yet seen among mid-winter ruby-throats on the Outer Banks. We're not sure whether other investigators who banded Ruby-throated Hummingbirds at or near Buxton saw molt in progress, but we don't think anyone has ever recaptured any banded hummers over a long enough time to determine how long it would actually take a RTHU wintering on Hatteras to complete its primary molt. It would be a fascinating topic to study--and to compare with how long it takes on our Central America study sites within the species' "traditional" wintering range. In addition to making detailed notes about molt in this female ruby-throat at our alternate site in Buxton, we banded her (#H81301) and took the usual measurements. For reasons we shall explain below it was important to know she weighed a healthy 3.39g.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center By now it was late afternoon at the alternate site and even though it appeared there might be a third ruby-throat present we decided to pack our gear and return to the primary location where we had banded six hummers at the home of our friend. We chose to do so because at about 4 p.m. the day before we had our only sighting of a young male RTHU with several ruby-red throat spots and thought he might return at the same hour. We erected the trap outside the office window by 3:55 p.m. and--just like clockwork--the distinctively marked immature male ruby-throat soon came into view and entered the trap. In-hand we could see this bird had moderate throat streaking and five iridescent red gorget feathers. The scale indicated he weighed 3.22g. With dusk approaching and no other unbanded hummers in sight, we pulled the trap and shut down operations for the day, more than a little pleased that at our friend's home in Buxton we had banded a total of seven winter Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (five females, two immature males), plus two more females at the alternate site. With that we again retired to the comfort of our friend's home for an evening of good food and great conversation. After a restful night we arose early for that long, nine-hour drive back to Hilton Pond Center where we began compiling this photo essay about our weekend of banding at Buxton.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center If you've stuck with us this far you know a little more about eastern North Carolina and about how we trapped and banded nine Ruby-throated Hummingbirds during midwinter on the Outer Banks. What we haven't mentioned so far is what we think is going on with this winter population of a species that historically departed temperate North America to spend cold months in sunny, tropical Central America. In the first place, that warmth-loving ruby-throats can survive at all during winter on the Outer Banks undoubtedly is in large part due to the nearness of the Gulf Stream. This current of warm water comes up from South America and flows past the Outer Banks less than ten miles offshore, moderating temperatures enough to make Hatteras Island a suitable mid-winter hangout. Of course, even though the Gulf Stream has been this close for millennia there were NO reports of winter ruby-throats in North Carolina before about 1995 or so. The Gulf Stream obviously helps, but these days we think tiny hummingbirds on Hatteras are benefiting from a small but significant increase in annual winter temperatures. We hesitate to call this phenomenon "global warming" because the phrase elicits such knee-jerk reactions in some folks, so maybe we should just refer to it as "global climate change."

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Mountaintop glaciers melting . . . polar ice fields shrinking . . droughts worsening . . . severe storms increasing . . ocean levels rising (and even affecting dunes and beaches at Cape Hatteras National Seashore) . . . and now "cold weather wimp" Ruby-throated Hummingbirds wintering where they never have before; these ALL appear to be indicators the Earth's atmosphere is warming. It may take only a few degrees difference to affect all these systems marginally or, worse yet, to produce devastating effects. We won't point fingers and say human activity is the cause of global climate change--although it well may be a significant factor--but based on what we've heard from a plethora of scientists in widely diverse disciplines we see no honest way to deny "global warming" is occurring. Maybe it's just part of a natural cycle and perhaps we can't do anything to stop it, but it's happening, and wouldn't it be really neat if--because of their recently acquired ability to survive WITHOUT migrating to the Neotropics--Ruby-throated Hummingbirds are THE species that finally drives home the point that global warming is for real?

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center POSTSCRIPT (Defusing a potential counter-argument): As noted in our narrative above, all seven Ruby-throated Hummingbirds we banded at the home of our friend on the Outer Banks at Buxton appeared to be in fine shape. None showed any sign of weather-related stress or illness, and all were within--or even a little above--the expected weight range for a healthy ruby-throat. Climate change naysayers might at this point interject the argument that these hummers were surviving because the homeowner had altered the system with an assortment of heated feeders that warmed the sugar water mix and even the hummers themselves. Initially this might seem to be a valid argument, but the situation on Hatteras Island is sort of a controlled experiment--with the control being two houses a mile away where ruby-throats were visiting feeders that were NOT heated. We banded two female RTHU at one of these houses and both those birds also were in good health and had optimal weights. And don't forget that one of those alternate-site birds was halfway through her primary wing feather molt, a pretty good indicator the hummer was healthy AND getting plenty of proteins and fats from tiny insects that themselves may be able to survive because annual winter temperatures are a few degrees warmer. The REAL question may be whether feeders in general, heated or not, are enabling Ruby-throated Hummingbirds to survive current winters on Hatteras Island, and that's a harder hypothesis to test. All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center |

|---|

The Piedmont Naturalist, Volume 1 (1986)--long out-of-print--has been re-published by author Bill Hilton Jr. as an e-Book downloadable to read on your iPad, iPhone, Nook, Kindle, or desktop computer. Click on the image at left for information about ordering. All proceeds benefit education, research, and conservation work of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. The Piedmont Naturalist, Volume 1 (1986)--long out-of-print--has been re-published by author Bill Hilton Jr. as an e-Book downloadable to read on your iPad, iPhone, Nook, Kindle, or desktop computer. Click on the image at left for information about ordering. All proceeds benefit education, research, and conservation work of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. |

|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

If you Twitter, please refer

"This Week at Hilton Pond" to followers by clicking on this button: Tweet Follow us on Twitter: @hiltonpond |

Comments or questions about this week's installment? Send an E-mail to INFO. (Be sure to scroll down for a tally of birds banded/recaptured during the period, plus other nature notes.) |

Click on image at right for live Web cam of Hilton Pond,

plus daily weather summary

Transmission of weather data from Hilton Pond Center via WeatherSnoop for Mac.

|

--SEARCH OUR SITE-- For a free on-line subscription to "This Week at Hilton Pond," send us an |

|

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond." Please see Support if you'd like to make a gift of your own.

|

If you enjoy "This Week at Hilton Pond," please help support Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. It's painless, and YOU can make a difference! (Just CLICK on a logo below or send a check if you like; see Support for address.) |

|

Make credit card donations on-line via Network for Good: |

|

Use your PayPal account to make direct donations: |

|

If you like shopping on-line please become a member of iGive, through which 950+ on-line stores from Amazon to Lands' End and even iTunes donate a percentage of your purchase price to support Hilton Pond Center.  Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase through them earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause!Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase through them earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause!Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. |

|

BIRDS BANDED THIS WEEK at HILTON POND CENTER 8-16 January 2012 |

|

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS WEEK: * = New species for 2011 WEEKLY BANDING TOTAL 3 species 8 individuals 2012 BANDING TOTAL 5 species 22 individuals 31-YEAR BANDING GRAND TOTAL (since 28 June 1982, during which time 170 species have been observed on or over the property) 125 species (31-yr avg = 65.7) 57,110 individuals (31-yr avg = 1,842) NOTABLE RECAPTURES THIS WEEK Carolina Chickadee (1) Northern Cardinal (3) White-throated Sparrow (1) House Finch (1) This Week at Hilton Pond

|

OTHER NATURE NOTES: --For a complete list of the 74 non-Ruby-throated Hummingbirds we've banded since 1991 (see photo essay above)--including two Rufous Hummingbirds at Hilton Pond Center--visit our page on Vagrant & Winter Hummingbird Banding. Included are hints about caring for winter hummers and speculation about what might be causing their apparent increase in the eastern U.S. --A White-throated Sparrow mist netted on 10 Jan had been banded at the Hilton Pond in Nov 2006 as a bird of unknown age and sex. According to Bird Banding Lab protocol, this individual is now and after-sixth-year bird and the oldest of its species for the Center. The sparrow's aluminum band--worn very thin--was indicative of its age. --The near-absence of winter songbirds continues around Hilton Pond, with Mourning Doves and House Finches the only species with counts of more than a half-dozen or so. (Turkey Vultures and Black Vultures seem especially common overhead--which we hope is not some sort of indicator.) Rather than filling our giant sunflower tube feeders thrice every week like last winter, seeds are going so slowly that once-per-ten-days is the current rate. Normally January and February are our most productive banding months, but through the first of the year we've handled only 22 birds of five species. Woe is us! All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center |

We've caught rufous as early as 6 August at nearby Sharon SC

We've caught rufous as early as 6 August at nearby Sharon SC  Ruby-throats, which occur commonly during the breeding season in the eastern U.S. and across southern Canada, are mostly what we call "cold-weather wimps" whose autumn departure for the Neotropics typically precedes our first frost and subsequent reduction in flowering plants and flying insects. In fact, in

Ruby-throats, which occur commonly during the breeding season in the eastern U.S. and across southern Canada, are mostly what we call "cold-weather wimps" whose autumn departure for the Neotropics typically precedes our first frost and subsequent reduction in flowering plants and flying insects. In fact, in

The road wound near Bodie Island Lighthouse and across the amazing Bonner Bridge over Oregon Inlet

The road wound near Bodie Island Lighthouse and across the amazing Bonner Bridge over Oregon Inlet

since we could see two or three zipping about--investigated the trap and entered to feed at exactly 2 p.m., at which time we flicked an electronic trigger that caused a trapdoor to slide shut. The trap now held what appeared to be the first Ruby-throated Hummingbird we'd ever caught in North America during winter.

since we could see two or three zipping about--investigated the trap and entered to feed at exactly 2 p.m., at which time we flicked an electronic trigger that caused a trapdoor to slide shut. The trap now held what appeared to be the first Ruby-throated Hummingbird we'd ever caught in North America during winter.

Oct 15 to Mar 15:

Oct 15 to Mar 15: