|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

|

|

|

BAT IN THE BATHROOM, Here at Hilton Pond Center we heat the old farmhouse and office with wood in part by salvaging a surprising amount of deadfall from a young mixed woodland that now covers much of our 11 acres. More important, each year favorite brother Stan Hilton (below) brings us several trailer loads of firewood that HE salvages from a golf course near his home.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Splitting Stan's gift wood and feeding our woodstove three or four times per day are hard work, but significant funds we save annually on heating costs can then be directed toward the Center's initiatives in education, research, and conservation. (In keeping with the latter, a catalytic combuster and properly adjusted damper on a modern woodstove make us confident our wood burning is not excessively fouling the atmosphere.) Although wood heat is a money-saver and quite comfy, it makes our indoor air bone-dry--a situation we remedy by placing open pots of water atop the woodstove to maintain humidity. We get THAT water by saving into a plastic watering can what we run each morning as we wait for the tap to get hot enough for face-washing. We keep the watering can (below) beside the bathroom tub for easy access. Imagine our surprise one day this week when wife Susan presented us with the half-full watering can and, pointing inside, calmly asked "What is THIS?" Floating therein was a dark furry brown object we quickly recognized, so our equally calm response was "Hmmm. It seems to be a dead bat." Susan, supportive nature lover that she is, was neither alarmed nor frightened; in fact, to her credit she said she felt sorry for the bat while asking us to be rid of it. Immediately.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center As we toted the watering can and contents onto the back deck, Susan's follow-up question was "Where'd this bat came from in the first place?" She suggested the animal rode indoors on firewood, but we didn't think that possible because we handle every stick of wood as we place it in our log carrier and bring it in to load the stove. More likely it had been hibernating in one of the farmhouse's several unused chimneys and--perhaps awakened by unusually warm January weather--dropped down, emerged through an open fireplace, and flew about the house undetected until entering the bathroom. Undoubtedly thirsty, the bat probably sensed moisture in the watering can, entered to drink, and was unable to climb back out because of the can's smooth plastic sides.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Bats are part of our regular nighttime fauna at Hilton Pond Center. Most evenings spring through autumn--and even on really warm winter days--we see several smallish bats swooping over the pond itself, performing their much-appreciated task of eating mosquitoes and other flying insects. However, we seldom see bats by day, much less in winter . . . in the house . . . floating in a watering can. Being aware bats sometimes do carry rabies, we carefully poured the floating carcass from the can, sterilized the latter with hot soapy water, let the bat dry out for a few hours in crisp winter air, put on a pair of surgical gloves as a reasonable precaution, and brought the dead but otherwise perfect specimen (above) back inside for photos and to see what we could learn from this surprise winged visitor. We must admit taking pictures of a dead bat is far easier than photographing a live one--especially when trying for close-ups.

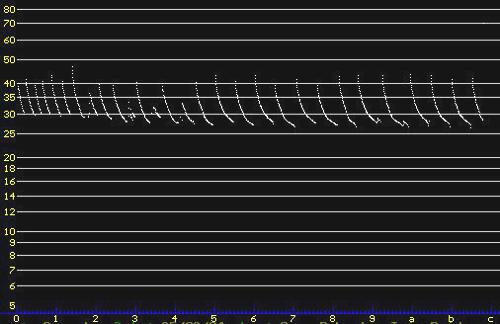

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Being nocturnal, bats are not fully understood nor sufficiently studied no matter where they occur. Information about them in the Southeast is especially sketchy. Menzel et al. (2003) compiled South Carolina information on bats identified through museum specimens, field surveys, and reports to SC Department of Natural Resources and determined there were 14 kinds of bats in the Palmetto State (see Table 1 above). Six occur statewide, while just eight species are "common" within the Piedmont Region where Hilton Pond Center is situated. (We speculate the Piedmont's relatively low bat diversity is due in part to the absence of natural caves like those found in the Blue Ridge Mountains; in fact, many Piedmont bat populations may depend on old buildings as communal roosting states, those buildings acting as artificial caverns. Big, hollow trees likely serve as "caves" in Lowcountry swamps and across vast undeveloped areas of the Sandhills. Province.) Within South Carolina, swamp-dwelling Rafinesque's Big-eared Bat is state-endangered and four other species are threatened or of special concern. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Even up-close some bats are hard to identify, so the best way to know what you've got may be via a "bat detector" that records and analyzes species-specific clicks and calls as bats fly overhead. (The sonogram above is a visual representation of the call of a Big Brown Bat. CLICK on the image to hear the call as rendered by the bat detector that reduces high frequencies to human-hearable levels.) To date we've been confident in listing three species on the Center's bat inventory--all from live in-hand specimens: The unmistakable Red Bat, Lasiurus borealis; Tri-colored Bat, Perimyotis subflavus (formerly called Eastern Pipistrelle, Pipistrellus subflavus); and Big Brown Bat, Eptesicus fuscus. We suspected our watering can bat was the latter but wanted to take some measurements and examine it more closely with a "Field Key to Bats" on our desktop.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Bats--with dense, soft fur (above) covering most of their bodies--are, of course, mammals; their wings and ears are naked but faces and tails are more or less furred, depending on species. As mammals, female bats give live birth and nurse their young.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Bats comprise their own mammalian order, Chiroptera, which means "winged hand." Much of a bat's wing is skin stretched between extremely elongated finger bones--quite unlike birds in which the wing is made of feathers attached to bones of arm and hand. In the photo above, our bat's pinkie finger extends down and to the right--note the large knuckle--with ring, middle, and fore fingers above the pinkie. The thumb is barely visible out to the left; it shows better in the image just below.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Folks are often surprised to learn the flying surface of a bat isn't limited to skin of arm and hand. In fact, the skin flap of the wing is continuous along the bat's flank all the way to the uropatagium (above)--a membrane that in most bats stretches between the rear appendages and includes the tail. In flight bats occasionally grab insects with their mouths, but for the most part they use the uropatagium to scoop up prey. The bat then bends down while still flapping, gobbles insects from the scoop, and continues on its way in pursuit of the next prey item.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Even though they're classified as chiropterans, many folks mistakenly think the bat is a high-flying rodent; on the contrary, bats don't have big front incisors and aren't in Rodentia at all. A head-on view (above) reveals not flattened incisors but sharp little canine teeth. Adapted for stabbing into insect bodies, the molars are also pointed--another indication bats can't be rodents. (This entire taxonomic problem is further complicated by the German language in which the term for bat is fledermaus, literally "flutter mouse.")

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center All North American bats are nocturnal (or crespuscular) microchiropterans--literally translated as "little hand wings." The phrase "blind as a bat" is quite misleading because microchiropterans DO have eyes (above); these are small but still functional. In contrast, the macrochiropterans--Old World Fruit Bats and "Flying Foxes" that sometimes are diurnal--have very large eyeballs and presumably sharper vision than their beady-eyed cousins.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center After looking at all the external attributes of our bathroom bat, we concluded the specimen was what we had first suspected: Big Brown Bat. Our decision was based on the bat's overall appearance--relatively short and wide ears and fur color, for example--but primarily because of its large forearm measurement of 48mm. Big Brown Bats look small in the hand--body size is about that of a domesticated white mouse--but several other South Carolina bats are much smaller; Tri-colored Bat, for example, has a forearm only 33-36mm long. In further support of our identification we looked closely for a keel (rounded flap of skin) on the calcar (AKA calcaneus), a needle-like cartilaginous spur that points from the ankle; in the photo above, the calcar is barely visible through the skin as a pinkish-yellow vertical structure. We also examined the shape of the bat's tragus--that flap in front of the ear that deflects sound and helps the bat ecolocate. All these characters plus the forearm measurement confirmed our specimen's ID as Big Brown Bat. This was not a new bat for the Center, but it was good to know the species is still present. (Incidentally, this bat's name is why we insist common names of flora and fauna are proper nouns that always should be capitalized for clarification. There's a lot of difference between a Big Brown Bat, Eptesicus fuscus, and a generic "big brown bat" that could be any of many species.)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Big Brown Bats are probably doing as well as might be expected considering habitat loss, insecticide use, and other problems we humans throw at them, but some of North America's cave-dwelling colonial bats are in big trouble due to a recently discovered menace known as White Nose Syndrome. This devastating malady--caused by a fungus that grows on hibernating bats' muzzles (as on the Little Brown Bats above)--leads to a variety of metabolic, physiological, and behavioral changes that almost always result in death. More than a million U.S. and Canadian bats of several species have died since 2007, with mortality rates exceeding 90% in some caverns. Mammalogists are concerned those populations will never recover, so scientists are working feverishly to find a way to halt the epidemic. Curiously, the fungus that causes White Nose Syndrome occurs naturally in Europe and seems to cause no harm to bats there; it may be this European strain somehow was introduced to North America where our native bats have not yet acquired immunity. No one is positive about how a European fungus got here, but as humans began traveling and transporting goods worldwide with ease, similar problems have occurred time and time again--as in Chestnut Blight, Dutch Elm Disease, Hemlock Woolly Adelgid, and Japanese Beetle, to name just a very few. (NOTE: We doubt the Big Brown Bat we encountered at the Center this week was a White Nose victim, although we can't know for sure. The delicate fungus would have washed off in the watering can, removing external evidence of any infection. Besides, some experts believe this particular bat species is less susceptible to the disease.)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We regret the loss of any bat whether from White Nose Syndrome or drowning in a watering can. Thus, this spring we'll make small amends by constructing and erecting a couple of new homes for bats at Hilton Pond Center. We encourage our readers to follow suit. Bat boxes are fairly simple to make and you can find instructions for a variety of configurations on-line. We doubt we'll be installing one of those massive Florida-style free-standing bat condominiums, but in between our firewood-splitting sessions we WILL find time to make and mount one or two small bat homes near attic louvers on the old farmhouse at Hilton Pond Center. We'll also see if we can't restrict fireplace access a little so no more bats come down a chimney and end up floating in our bathroom watering can. POSTSCRIPT: After posting the above account we got an interesting e-mail from Paul R. Moosman Jr., assistant biology professor at Virginia Military Institute. Dr. Moosman is a bat specialist intrigued by the scattering of little round marks in our photo of the Big Brown Bat's wing (close-up below right). All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center |

|---|

The Piedmont Naturalist, Volume 1 (1986)--long out-of-print--has been re-published by author Bill Hilton Jr. as an e-Book downloadable to read on your iPad, iPhone, Nook, Kindle, or desktop computer. Click on the image at left for information about ordering. All proceeds benefit education, research, and conservation work of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. The Piedmont Naturalist, Volume 1 (1986)--long out-of-print--has been re-published by author Bill Hilton Jr. as an e-Book downloadable to read on your iPad, iPhone, Nook, Kindle, or desktop computer. Click on the image at left for information about ordering. All proceeds benefit education, research, and conservation work of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. |

|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

If you Twitter, please refer

"This Week at Hilton Pond" to followers by clicking on this button: Tweet Follow us on Twitter: @hiltonpond |

Comments or questions about this week's installment? Send an E-mail to INFO. (Be sure to scroll down for a tally of birds banded/recaptured during the period, plus other nature notes.) |

Click on image at right for live Web cam of Hilton Pond,

plus daily weather summary

Transmission of weather data from Hilton Pond Center via WeatherSnoop for Mac.

|

--SEARCH OUR SITE-- For a free on-line subscription to "This Week at Hilton Pond," send us an |

|

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond." Please see Support if you'd like to make a gift of your own.

|

If you enjoy "This Week at Hilton Pond," please help support Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. It's painless, and YOU can make a difference! (Just CLICK on a logo below or send a check if you like; see Support for address.) |

|

Make credit card donations on-line via Network for Good: |

|

Use your PayPal account to make direct donations: |

|

If you like shopping on-line please become a member of iGive, through which 950+ on-line stores from Amazon to Lands' End and even iTunes donate a percentage of your purchase price to support Hilton Pond Center.  Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase through them earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause!Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase through them earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause!Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. |

|

Most consist of rough-surface plywood sheets hung vertically

Most consist of rough-surface plywood sheets hung vertically  His comment: " . . . it certainly looks like this particular bat has had White Nose Syndrome (WNS) in the past. If you look on the wing photos you took you can see tiny round scars. I would wager that if you backlit the wing you would notice even more areas lacking pigment. These most likely were caused by the fungus associated with WNS." Dr. Moosman further suggested we send the photo to a specialist working with White Nose Syndrome, which we shall do. Better yet, our bat carcass is frozen solid in the freezer and available for necropsy if we find someone interested in sampling it for WNS. Since our bathroom bat was found floating in the watering can, it seems likely it died from drowning, but that it had old scars on its wing is evidence of what we've read about Big Brown Bats not being as likely to die from White Nose Syndrome. We're not sure how well-documented the fungal disease is among South Carolina bats, but we hope to find out soon.

His comment: " . . . it certainly looks like this particular bat has had White Nose Syndrome (WNS) in the past. If you look on the wing photos you took you can see tiny round scars. I would wager that if you backlit the wing you would notice even more areas lacking pigment. These most likely were caused by the fungus associated with WNS." Dr. Moosman further suggested we send the photo to a specialist working with White Nose Syndrome, which we shall do. Better yet, our bat carcass is frozen solid in the freezer and available for necropsy if we find someone interested in sampling it for WNS. Since our bathroom bat was found floating in the watering can, it seems likely it died from drowning, but that it had old scars on its wing is evidence of what we've read about Big Brown Bats not being as likely to die from White Nose Syndrome. We're not sure how well-documented the fungal disease is among South Carolina bats, but we hope to find out soon.

Oct 15 to Mar 15:

Oct 15 to Mar 15: