- Established 1982 -HOME: www.hiltonpond.org

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center BIRDS OF A FEATHER: The lead question this week at Hilton Pond Center: What do birds, mammals, and reptiles have in common? Well, let's see. Birds fly--including hummingbirds like the adult male above--but reptiles don't, and among mammals the only true fliers are chiropterans such as the Eastern Red Bat (below). Other mammals and some reptiles are aerobatic, but they glide rather than fly; thus, among the three groups flight is not a common characteristic.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Well, then, many mammals and reptiles are quadrupeds, but birds are strictly bipedal and snakes and some lizards have no legs at all. And with the exception of monotreme mammals--four Echidnas and the Duck-billed Platypus--egg-laying applies only to reptiles and birds, and even some snakes and lizards give live birth. So do all three groups feed their own young? Nope, that works for birds and mammals, but not in the reptile world.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center All these differences among the three taxonomic classes--Mammalia, Reptilia, and Aves--suggest there may be just a few very basic commonalities, as follows (although you may think of others): All birds, mammals, and reptiles (male Carolina Anole displaying, above) are bony-bodied vertebrates, all are bilaterally symmetric, and all have eyes (bats included), but that's about it. Oh, and one other: All three groups have skin appendages made of the fibrous protein "keratin," even though those appendages look very different and serve diverse functions. To wit: Reptiles have bodies almost entirely covered by keratinous scales, most mammals have copious keratinous hair (except for us "naked apes"), and birds have keratinous feathers.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Scales, hair, and feathers are homologous (with skin appendages having protection as their function) but are obviously not identical, even though all arise from locations on embryonic skin called "placodes." Each placode tells skin cells at that spot to stack up and harden to form the structure unique to each of the three groups of organisms. Placodes also determine the density and patterns of skin appendages; this results in different textures of hair/fur on different body regions of any given mammal, and yields various kinds of plumage on different parts of a bird's anatomy (e.g., the Barn Owl wing feather above is very different from the owl's down feathers).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In all three classes of organisms, skin appendages are replaced--compensating for wear and tear--sometimes on a very precise timeline. Lizards and snakes (Rough Green Snake, above) shed their entire scaly covering whenever needed, allowing for growth; most mammals lose and replace hair/fur on a fairly constant basis (at least until, in humans, male-pattern baldness sets in!); and, birds gradually lose and replace ALL their feathers sequentially at least once per year--which brings us to the real subject of the current photo essay: "Hummingbird Molt."

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our interest in molt sequencing by Ruby-throated Hummingbirds is long-standing--we've been banding and seriously observing hummers for 38 years (including 30 Operation RubyThroat trips to Central America)--but that interest was piqued this week when we captured an adult male (above) going through some serious feather replacement. He had lost nearly all his flank feathers on both sides while bringing in new ones AND was molting some of his crown feathers.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Just above is a closer view of that male. It shows a bony horizontal ridge (the keel bone or sternum), covered by a thin layer of skin in which blood vessels are visible. Above and below the keel are dark masses; these are the relatively enormous pectoral muscles that enable incredibly fast wingbeats of a hummingbird. In mammals, keratin is laid down inside the follicle at the hair base, causing the hair shaft to elongate more or less continuously--as with head and facial hair in humans. (Some human hairs grow to a more or less determinate length, fall out of the follicle, and are replaced regularly by an entirely new hair shaft.) By comparison in birds, the feather shaft is enclosed in a semi-transparent keratin sheath that fragments as the feather grows and elongates from within the follicle. As the sheath breaks away--producing "feather dander" that aggravates allergies in some folks--the feather slowly unfurls, eventually revealing its typical structure. In our photo above of the male hummer the flank feathers at left are "in quill" (i.e., fully sheathed), while those on the right are in various stages of being exposed. (NOTE: If you've ever seen or felt "pinfeathers" while preparing a Thanksgiving turkey, those are body feathers--probably down--that are still ensheathed.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When capturing birds during molt--note plentiful quills above on the forehead of an adult female ruby-throat captured in late summer--a bander must be careful not to bend an ensheathed feather for a couple of main reasons. For one, the feather itself is non-living keratin protein, but the feather follicle is filled with blood vessels that nurture the growing feather; if the base of the sheath is damaged the follicle will bleed. In addition, bending a feather still in quill can cause it to be malformed as it unfurls.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When a hummingbird hatches from its egg, it is blind, helpless, and essentially naked; in the photo above, there are just a few plumes on the nestling's back. (NOTE: Among all the 340-plus hummingbird species in the Americas, nearly all have a two-egg clutch. The second egg in the nest above may be late to hatch, or it might be infertile.) Those first few days post-hatch are a critical time because a naked chick cannot yet thermoregulate, so if the female is off the nest too long or if weather is particularly wet or cold the nestling(s) can perish from hypothermia.

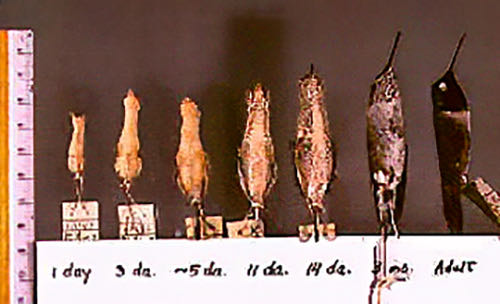

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The photo just above is a series of study skins from the Bell Museum of Natural History at University of Minnesota (where bander Hilton did his graduate research on Blue Jays). You'll notice the inch-long chick on hatch day is indeed featherless; it doubles its mass by Day Three but is still essentially naked when mass doubles again at Day 5. By Day 11 more feathers appear, growing in "tracts" along the nestling's flanks; these are more obvious at the two-week mark. (NOTE: There are similar tracts down a bird's back and along the "drumstick"--i.e., the muscular part of the upper leg.) People are often surprised to learn that--except for penguins--feather follicles do not occur on every square millimeter of a bird's body. Instead, when feathers in the tracts break out of quill and lengthen, they overlap and provide protection to bare skin beneath--as in the three-month-old immature male and full adult male above right.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We handle quite a few Ruby-throated Hummingbirds here at Hilton Pond Center--120 so far in 2021 and 6,765 since 1984--so we've had ample opportunity to examine RTHU molt condition within their North American breeding range. When adult males (above) arrive here in spring (as early as the last week in March) their plumage is absolutely pristine--which makes sense; since they were last here they've acquired a whole new set of feathers that show very little wear, and they're ready to attract females with their spiffy new wardrobes. The iridescent springtime gorget appears solid red--sometimes with a hint of bronze as in the bird above.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A week to ten days after the first males show up here at Hilton Pond, adult females (above) start arriving. They, too, have sparking new plumage: Metallic green on crown and back, with white belly and throat--although the gorget may have faint to moderate gray streaking. (NOTE: Older females often have more and darker streaking; the one above was a rather elderly, streak-throated, 6th-year bird at the time of her recapture this spring.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After female RTHU arrive in spring migration they quickly get down to the business of building nests, mating, laying eggs, and incubating (above). At Hilton Pond Center first chicks likely hatch the first week in May and fledge by month's end; our earliest banding of a fledgling was on 4 June, although more typical dates for free-flying youngsters are a month later than that.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Fledgling females look pretty much like their mothers, with more or less gray streaking on otherwise white throats, while young males (both photos above) show a wide diversity of gorgets. Some male fledglings closely resemble females, but most have a degree of darker streaking on their gorgets--we call it a "five o'clock shadow." As the season progresses young males often acquire one or more metallic red throat feathers (above left), and a few will have gorgets that are much fuller (above right) by the time they migrate south in late summer or early fall.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We should point out that in rear view (above) young males are essentially indistinguishable from females of any age. Their backs are metallic green AND the tips of the outer tail feathers are white, as shown. In the close view above you can also see back feathers of young RTHU have buffy edges that wear off over time. In adults these back feathers are uniformly green.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Note that individual tail feathers of females and young males are more or less broad and about the same length, causing the tail to be rounded. This configuration is quite different in the adult male (above) whose tail feathers are pointed with outer ones longer--making the tail forked. There's also no female/young male white on the outer tail tips of adult males. To summarize our narrative: On the breeding grounds in North America, adult male Ruby-throated Hummingbirds are distinctive with full red gorgets and forked tails with pointed feathers that bear no white. Females of any age have more or less white throats (sometimes with light streaking) and tails that are rounded and with wide, rounded feathers, the outer ones showing white tips. Young males resemble females and have similar tails, but their throats usually have dark streaks and one to numerous red metallic feathers. All RTHU age and sex classes may commence body molt before fall migration, replacing some head, body, and throat feathers to varying degrees, but wing and tail feathers are not molted by southbound migrants unless lost incidentally.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As shown during Operation RubyThroat's extensive studies of our study species in Central America--including 1,540 RTHU banded in four countries there--autumn arrivals in the Neotropics continue body molt and sooner or later begin the more critical task of bringing in new wing and tail feathers. Young males (above, in Costa Rica in early February) often look a bit ragged as their white, gray-streaked juvenal throat feathers blend with new quills that eventually open to produce an adult's red gorget.

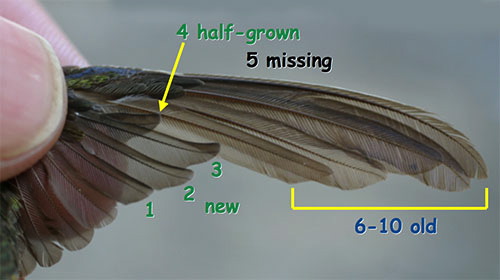

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center And then there's wing molt. Like all hummers, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds have ten primaries (above)--the outermost feathers on the wing that are most responsible for flight. These primaries are numbered one through ten, from the inside to the lead edge, as shown in the photo above. On RTHU non-breeding grounds in the Neotropics, primaries are molted sequentially--not all at one time, lest the hummer be grounded--starting with #1 and moving outward. In this Costa Rica photo from January, #1, #2, and #3 are freshly molted, #4 is half-in-quill, #5 is missing (its tiny quill not yet visible), and #6 through #10 are all old, faded, and somewhat worn. Incidentally, wing molt in hummers is usually symmetrical; for example, the #3 feathers on both wings are lost and replaced at the same time.

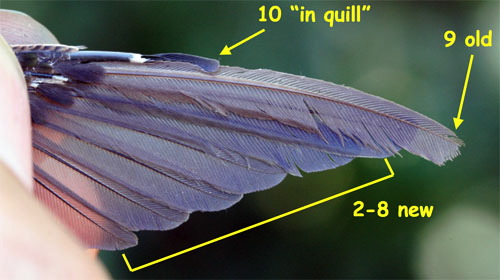

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center There is one little caveat to this primary molt sequencing, as we discovered on our very first Operation RubyThroat expedition to Costa Rica in 2004: RTHU wing molt does indeed start with #1 and move outward, but as shown above the hummers skip #9, bring in #10, and then come back and replace #9 last. We have thought long and hard about this apparent anomaly, finally hypothesizing that since #9 is the biggest and broadest feather on the wing it might be the one a hummer would want to have freshest before departing on the long migration north. We're certainly open to other hypotheses you might have; contact us at INFO. (Again, wing molt does not occur on the breeding grounds among migrating Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, although those relatively few RTHU that now overwinter in southeastern U.S. coastal areas undoubtedly show similar molt patterns.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center And, finally, the tail. Tail molt in ruby-throats is also sequential in the Neotropics. Hummers have five pairs of tail feathers and molt one pair at a time, beginning inside and moving out--pair #1, then pair #2, etc. (Again, losing all the feathers at one would make flight difficult.) Tail molt among Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in the Neotropics usually starts in January. (Tail molt is complete in the female tail above.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In the photo just above, a young, second-year male ruby-throat in Costa Rica was undergoing an unusual asymmetrical molt in which some heavily worn white-tipped juvenal tail feathers have been replaced by pointed black adult feathers.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center To our knowledge, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds do not leave the Neotropics until molt is complete--including body, throat, and flight feathers. (To depart during wing/tail molt would undoubtedly lead to catastrophe, especially for northbound individuals attempting a non-stop trip across the Gulf of Mexico.) Some individuals we have examined in Costa Rica have finished their molt by early February and may be among the first migrants to move north. However, In Belize in early March some male RTHU like the one above were still going through gorget AND wing/tail molt and likely would depart weeks later. It may be that ruby-throats observed as late as the first week of May in Costa Rica are younger birds that got a slow start on pre-migration molt; these will probably show up as late arrivals in North America come spring.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center It's apparent that feather molt in Ruby-throated Hummingbirds is no simple phenomenon. It is metabolically demanding and requires a steady flow of nutrients as old feathers (like the male gorget feather above) drop out and new ones come in during a process that can take a month or more. Malformed feathers may lead to a bird's inability to fly and forage, while poorly colored plumage may hinder finding a mate. Likewise, molting flight feathers at the wrong time could lead to disaster during long-distance migration. For us it is a wonderment that the hummingbird's intricate feather-making mechanism consistently makes near-perfect products we see while banding ruby-throats at Hilton Pond Center. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center HILTON POND SUNSETS "Never trust a person too lazy to get up for sunrise

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Sunset over Hilton Pond (above), 01 August 2021

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Sunset over Hilton Pond (above), 09 August 2021 Photoshop image post-processing for this page employs

Checks also can be sent to Hilton Pond Center at: All contributions are tax-deductible on your Don't forget to scroll down for Nature Notes & Photos, |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Dr. Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

|

|

--SEARCH OUR SITE-- For your very own on-line subscription to "This Week at Hilton Pond," |

|

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us, among other things, to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond" with students, teachers, and the general public. Please see Support or scroll below if you'd like to make a gift of your own. We're pleased folks are thinking about the work of the Center and making donations. Those listed below made contributions received during the period. Please join them if you can in coming weeks. Gifts can be made via PayPal (funding@hiltonpond.org); credit card via Network for Good (see link below); or personal check (c/o Hilton Pond Center, 1432 DeVinney Road, York SC 29745). You can also donate through our Facebook fundraising page. The following made contributions to Hilton Pond Center during the period 1-10 August 2021:

|

If you enjoy "This Week at Hilton Pond," please help support Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. It's painless, and YOU can make a difference! (Just CLICK on a logo below or send a check if you like; see Support for address.) |

|

Make credit card donations on-line via Network for Good: |

|

Use your PayPal account to make direct donations: |

|

If you like shopping on-line please become a member of iGive, through which 1,800+ on-line stores from Amazon to Lands' End and even iTunes donate a percentage of your purchase price to support Hilton Pond Center.  Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase through them earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause! Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase through them earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause! Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. |

|

BIRDS BANDED THIS WEEK at |

|

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS PERIOD: * = new banded species for 2021 PERIOD BANDING TOTAL: 2021 BANDING TOTAL: 40-YEAR BANDING GRAND TOTAL: (Banding began 28 June 1982; since then 173 species have been observed on or over the property.) 127 species banded 73,987 individuals banded 6,764 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds banded since 1984 NOTABLE RECAPTURES THIS WEEK: Downy Woodpecker (1) * New longevity record for species |

OTHER NATURE NOTES: --Through 10 Aug we banded 120 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, the second fasted we've reached that seasonal total in 38 years of hummer research at the Center. (We banded 128 RTHU by that date in 2016--the year we set our all time record of 373 for the species.) The majority of our RTHU bandings come during the second half of August and first two weeks in September, so we seem poised for a very good year. (CAVEAT: Of course, anything could happen this fall, with the bottom dropping out of the local hummer population at any given moment.) -As of 10 Aug, the Hilton Pond 2021 Yard List stood at 80--about 46% of 172 avian species encountered locally since 1982. (Incidentally, 78 of those species so far this year have been observed from the windows or porches of our old farmhouse! Best year so far was 111 species in 2020. If you're not keeping a --Our immediate past installment of "This Week at Hilton Pond" was about ratsnake taxonomy and monochromatic warblers. It's archived and always available on our Web site as Installment #747. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center |

|

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) Back to "This Week at Hilton Pond" Main Current Weather Conditions at Hilton Pond Center |

|

|

Also within the skin are feather follicles that are homologous to mammalian hair/fur follicles.

Also within the skin are feather follicles that are homologous to mammalian hair/fur follicles.

Please report your spring, summer &

Please report your spring, summer &