- Established 1982 -HOME: www.hiltonpond.org

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

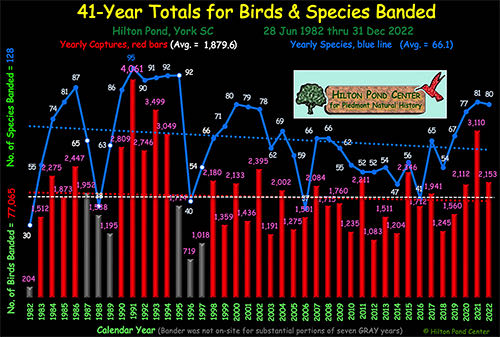

2022 BIRD BANDING SUMMARY: •• THUMBNAIL RESULTS •• At Hilton Pond Center we arbitrarily established 2,000 as a realistic round-number goal for how many birds we'd like to band each calendar year. We exceeded that goal for the 18th time in 2022 and finished with our 13th-most-productive year since 1982 with 2,153 bandings--above our 41-year average of 1,879.6. (The all-time high was 4,061 in 1991.) Even so, we finished with nearly a thousand fewer bandings than last year, primarily because there was no massive irruption of Pine Siskins as in the winter of 2020-21. We banded a total of 80 species in 2022, our 10th-highest-ever; the average number of species banded per year at the Center is 66.1. (The all-time high was 95 species, again in 1991.)

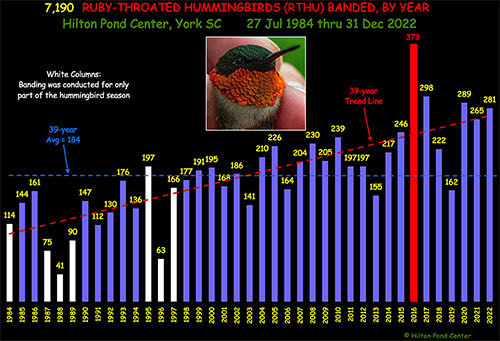

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Despite the near absence of Pine Siskins--we banded just one in 2022 (compared to 988 last year)--we did have significant numbers of wintering Purple Finches (253, adult male above) and American Goldfinches (398), the latter being our most commonly banded species for the year. Our 382 House Finches were close behind, but nearly all these were likely local breeders rather than seasonal migrants. The only other species with more than 100 bandings were Northern Cardinals (103) and Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, whose 281 total was our fourth-best for RTHU since we began studying them in 1984. The four top species just mentioned combined for 1,136 bandings, or 53% of the 2022 yearly total.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We added no new species to the Center's all-time banding list in 2022, although we did set new records for three species: 25 Downy Woodpeckers (up from 18, and a new record for the second straight year), 22 Northern Parulas (up from 20), and three Blackburnian Warblers (up from one). We also tied records for Yellow-throated Warblers (3, above) and Orange-crowned Warblers (2, below). We were surprised that despite a relatively low overall banding total, we banded 51 other species at or above their average annual number.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A chart showing all bandings by species for 2022--plus our 41-year highs, averages, and totals for Hilton Pond Center--are included in Table 2 at the end of this write-up. We welcome questions and comments via INFO. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center •• END-OF-YEAR THANKS •• Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project could not implement banding programs and other initiatives without the generosity of individuals who donate in support of our work in environmental education, conservation, and natural history research. We acknowledge these financial gifts individually throughout the year at the end of each installment of "This Week at Hilton Pond."

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In 2022 we were particularly grateful for contributions from several multiple-year "Top Tier Sustaining Donors" who were also citizen science alumni of one or more Operation RubyThroat Neotropical hummingbird expedition: All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center •• BACKGROUND INFO & METHODS •• We open our mist nets most days at Hilton Pond Center, but for bird welfare we don't deploy when it's too hot for us OR the birds (above 90 degrees or so) . . . or below 40 degrees . . or when it's windy . . or in the rain. Thus, weather limits our work, and climatic differences year-to-year at the Center have definite impact on banding results. Throughout most of 2022, temperature ranges were about average--although drought-like conditions during the summer and fall dropped the pond water level by nearly four feet by year's end. Heavy rains in December quickly alleviated the problem and the pond returned closer to full. December also brought brutally cold weather, with lows in the single digits on two nights when the pond skimmed over with ice.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Regardless of weather, we almost always run a few sunflower seed traps each day for songbirds (locations A, B & C around the old farmhouse on the Center's plat, above); late March through mid-October we also concentrate on trying to capture Ruby-throated Hummingbirds coming to sugar water traps dawn to dusk at those three locations.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We do not tally net- or trap-hours at Hilton Pond Center. (The photo above shows several styles of traps; a mist net in the background is still furled.) We find such accounting too complicated because of the way we have to operate--e.g., closing nets and traps periodically during the day to run errands, lead field trips, etc.--so we can't really compare actual "banding effort" from one year to the next. However, despite any annual variations in bander activity we believe things "average out" over time, and even without knowing actual hourly investment per annum our long-term banding studies still provide broader understanding of nature trends here in the Carolina Piedmont. Year-to-year differences in actual work-hours DO affect our banding results somewhat, but of greater significance is how the Center's overall landscape has changed during 41 years we've studied and resided here.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Under our laissez-fair land management philosophy, vegetational succession ensued and local habitats passed through stages, first from old field to shrub land (mostly invasives such as Chinese Privet and Russian Olive) and then to a dense stand of Eastern Red Cedar by about the 12th year. By Year 20 or so, many cedars were shaded out and killed by fast-growing deciduous trees, leading the transition to our current young forest of pine and sundry hardwoods with minimal shrubs or herbaceous ground cover. (We continue our never-ending effort to whack back invasives such as privet and toxic Nandina.) An aerial photo of Hilton Pond Center from March 2012 (above) shows how thoroughly the land had become covered by woody vegetation--mostly Loblolly Pines on the north edge, and hardwoods between the two ponds and on the southern half and eastern end of the property.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Deciduous trees these days at the Center are quite diverse with lots of Winged Elm and Sweetgum; scattered throughout are Black Cherry, Green Ash, Sugarberry, Flowering Dogwood, Red Maple, Box Elder, and various oaks and hickories. Several Baldcypresses have become well-established along the pond margin and are producing progeny. Just as vegetation has changed (current winter photo, above, with the pond barely visible), so has local bird life; with regard to banding, many species that hung out in vegetation close to the ground where our mist nets could snare them now fly uncaptured in treetops high above.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center It did not help our local bird life that in 1995 an adjoining farmer to the north of the Center clear-cut about 45 acres of mature Loblolly Pines and converted his land to pasture for beef cattle (see archival aerial image above). This apparently caused a nearly instantaneous drop in species that frequent pine lands, with populations declining drastically among numerous breeding species such as Blue Jays, Pine Warblers, and Brown-headed Nuthatches. Wintering species such as finches undoubtedly were affected by the loss of extensive cold-weather cover.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Speaking of vegetational change, Google Earth posted an aerial image (above) from January 2021 that shows the Center's old farmhouse and two massive fallen trees that were 125-150 years old. A giant White Oak (now a pale skeleton on the pond margin, at left in photo) snapped near its base in October 2014; an even taller Southern Red Oak (closer to the house and still covered by dark bark in the photo) tipped over violently on Easter weekend 2020 (photo below).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We're quite certain the demise of these two towering canopy trees has had negative impact on Center avifauna, especially since all that missing leaf surface no longer hosts caterpillars that fueled the activities of migratory and resident birds. Two positive aspects: 1) Departure of the two big oaks created new "holes in the sky" that provide a better view of sunsets AND of birds flying over; and, 2) We got lots of "free firewood" to feed the farmhouse woodstove. (On the personal side, losing these two venerable citizens of Hilton Pond Center was heart-wrenching--but that's the way nature works.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our banding activities and the landscape were disrupted for several days in late March 2022 when when we had a septic tank replaced and a new drain field dug. The septic lines were placed where there would be minimal disturbance to vegetation--that being the mostly open area beneath where the big Southern Red Oak had once grown.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The job was complicated because a 40-foot length of that giant oak--more than four feet in diameter--was still on the ground and in the way. The log had to be cut into still-massive eight-foot lengths that were muscled out of the way by a front-end loader. These remnants--too large to be reduced to firewood by equipment at hand at the Center--will eventually add to decomposing biomass.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Supplementing nature, on a year-round basis we offer local birds a LOT of food, primarily black oil sunflower seeds (above, with American Goldfinch, Carolina Chickadee, and Tufted Titmouse), plus white millet, cracked corn, shell corn, safflower, thistle (Nyger), dried mealworms, bark butter, shelled and unshelled peanuts, and various suet blocks. Our experiments with orange slices and grape jelly have failed to attract anything, including sought-after orioles. Spring through fall we hang at least two dozen feeders with sugar water for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds; in anticipation of western vagrant hummer species, we also maintain a couple of these even during winter. (NOTE: We've banded two fall Rufous Hummingbirds locally, both captured in traps. In September 2021 we also mist netted South Carolina's first record of a vagrant Broad-tailed Hummingbird.)

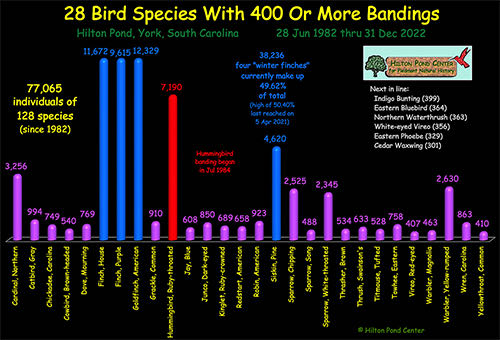

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Of equal or sometimes even greater importance than feeders, Hilton Pond itself and several much smaller artificial pools near the old farmhouse provide places for birds and other wildlife to drink and bathe. Accessible clean water often brings in more birds than does food--especially in winter when many drinking sources may be frozen solid. This is why we place a cold-weather heater in at least one of our water features (bird bath, above, with three Eastern Bluebirds, a House Finch, two Northern Cardinals, and an American Goldfinch). Incidentally, it's a good idea to place bathing containers close to the ground and near vegetational cover--shrubs, vines, or small trees--that provide an escape route from predators when a bird's feathers are wet and less able to support flight. Above all, keep the bird bath clean and filled with fresh water. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center •• 2022 BANDING DETAILS •• As shown an the chart below, the 2022 banding season ended with 2,153 birds banded from 80 species for Hilton Pond Center. These numbers were more than the 41-year average of 1,879.6 individuals (dotted white line on chart) and well above the species average of 66.1. (The chart's dotted red and blue statistical regression lines show an on-going moderate decline in both these categories.) This year's total was slightly more than half what we caught in our most productive year of 1991 (4,061 individuals). Diversity in 2022 was quite good but less than the record 95 species we caught, also in 1991. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The chart above shows an interesting increase in species diversity over the past four years, with 80 in 2022 tied for the tenth highest total since 1982. Most of that diversity came during spring and fall migration when we banded quite a few species we don't often capture. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The chart above shows 41-year cumulative totals for the 28 species banded most often at Hilton Pond Center. (Red-eyed Vireos and Common Yellowthroats joined the "400 Club" in 2022; Indigo Buntings probably will join in 2023.) American Goldfinches continue to lead the way with 12,239 bandings since 1982; they are ahead of House Finches (11,672) and Purple Finches (9,615) by relatively small margins. These three species plus Pine Siskins (4,620) are what we call the four "Winter Finches" (although HOFI and AMGO do occur here year-round, the latter in small numbers); these four totaled 38,326 bandings by the end of 2022, i.e., nearly half (49.62%) all birds captured. We always find it interesting the target species for our most intensive long-term study--Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--is the fourth-most-commonly banded species at the Center with 7,190 captured (since 1984). Our numerous sugar water feeders and plentiful nectar flowers undoubtedly play a role in local hummingbird abundance.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As shown in RED on comprehensive Table 2 at the end of this narrative, five species banded in this year at the Center exceeded or tied previous annual highs. Of particular interest were the 25 Downy Woodpeckers in 2022 that eclipsed the 2021 total of 18--which itself tied record a record set in 1994. (One of this year's DOWO was a very young male, above, banded on 1 September--quite late for a recent fledgling--and a bird that made us wonder if, despite the literature, downies ever double-brood. More likely it was the product of a second nesting attempt after a first nest had failed.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Northern Parulas (above) set a new record in 2022 at the Center with 22, up from 20 banded in in 2020. Prior to that we had never banded more than seven annually, so an average of 15 NOPA over the past three years shows a marked local increase--mostly during summer and in fall migration.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Three Yellow-throated Warblers and two Orange-crowned Warblers tied previous highs, so the only other other record-breaking tally was for three Blackburnian Warblers (above), up from one banded in each of three previous years. All these parulids are quite scare at Hilton Pond Center.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Of 80 species banded this year at the Center, 51 tied or exceeded their 41-year average. Of particular note were American Redstarts (spring female above), whose 57 bandings in 2022 missed last year's all-time-high by just one; AMRE are our second-most common Wood Warbler, with an average of 16 per year and a total of 658 since 1982. (By comparison, Yellow-rumped Warblers are our most abundant parulid with a total of 2,630, although this species has trended much lower annual numbers since its heyday in the 1990s--just 19 banded in 2022, compared to a record 425 in 1991.)

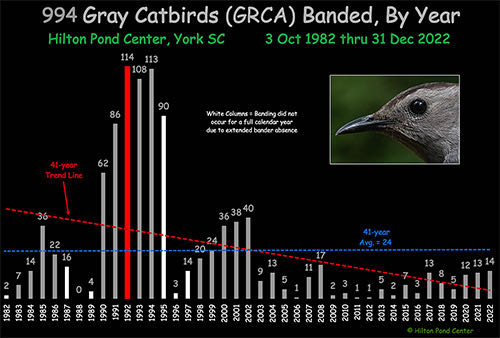

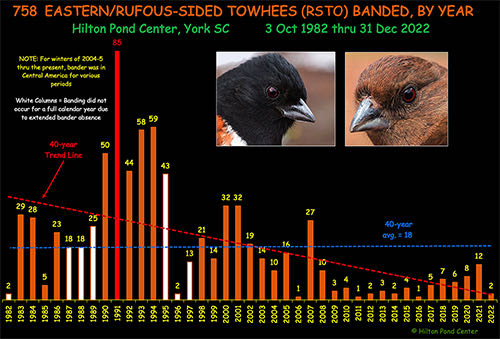

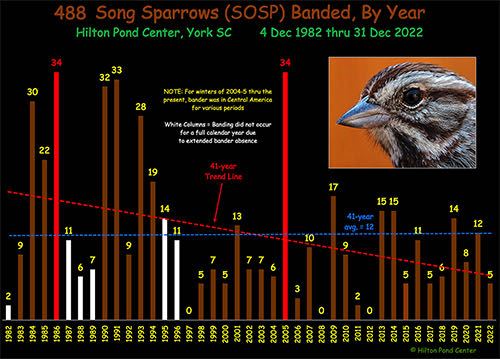

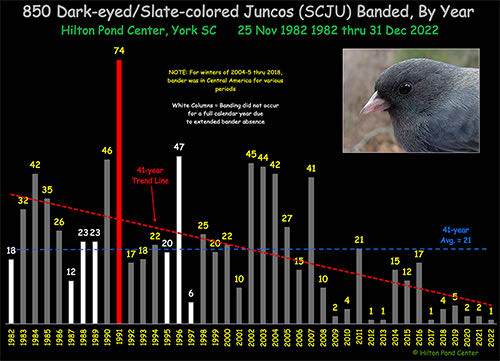

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Also of note in 2022 were 20 Cape May Warblers, surpassing the Center's 41-year average of 5. This species has shown a marked increase over the past four years with running tallies of 10, 24, 29, and 20; most years we band only one or two, although we had an inexplicable all-time high of 45 in 1991. The vast majority (91%) of CMWA are fall migrants, and most are not nearly as brightly plumaged as the hatch-year male above. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center It's likewise worth mentioning some of our BELOW-AVERAGE species--especially a few that we've banded at much higher levels in past seasons--Gray Catbirds, for example (see chart above). In 2022 we banded 14 GRCA--under the 41-year average of 24 and barely a tenth the all-time catbird high of 114 from 1992. And consider our Eastern Towhees (see chart below), whose two bandings this year were almost an all-time low and well below the 85 we handled in 1991. Incidentally, a third species that breeds locally but showed lower numbers than usual were Brown Thrashers; we banded four when expecting 13 (the average) and coming nowhere near the 1993 record of 59. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Song Sparrows (see chart below) show similar decline, with significantly more being banded in the 1980s and 90s than over the past decade. Interestingly, however, this very common sparrow is present at Hilton Pond only fall through spring--even though we lie right on the southernmost edge of the species' primary breeding range and have no summer records for SOSP. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center And then there are Dark-eyed Juncos (see chart below), which until about 15 years ago were among the most common winter residents beneath feeders at Hilton Pond Center. Most years we'd band two to four dozen, but their numbers have plummeted and this year we caught just one "snowbird"--a far cry from 74 in 1991. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Might catbirds, towhees, thrashers, sparrows, and juncos have something in common that led to precipitous banding declines? Well, all are birds of shrubby or weedy areas and in the past 41 years such habitats have nearly disappeared around the Center, so that's a possible explanation. There's also evidence catbirds, towhees, and thrashers were hit especially hard in the 1990s by West Nile Virus, while it may be juncos simply aren’t coming this far south these days because of warmer winters on breeding grounds up north. (Song Sparrows are even more of an enigma.) But who knows for sure? Cause and effect are always difficult to connect in nature, so all this is just speculation on our part--even though we remain ever hopeful our continuing long-term studies at Hilton Pond might provide even better hypotheses. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center •• 2022 "UNUSUAL" BANDINGS •• Folks often ask: "What's the most unusual bird you banded this year at Hilton Pond Center?" We're never quite sure how to answer except to look at numbers and respond with the name(s) of species we seldom band.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Using that criterion, and aside from the scarce warblers mentioned above (Blackburnian, Orange-crowned, and Yellow-throated), one of our least common birds banded in 2022 was--oddly enough--a solitary hatch-year European Starling (above). This nearly ubiquitous, non-native invasive species can be seen most days not far from Hilton Pond, but we seldom encounter it on or over the property. We've captured only nine EUST in 41 years, a low number for which we are ever grateful! Four other warblers we banded in 2022 are also among species that qualify as "uncommon" at Hilton Pond Center. These include the following:

Of the 27 Black-throated Green Warblers banded locally, 26 have been captured during fall migration. In 2022 we caught just one (immature of unknown sex above), although we've banded as many as five in one year. Most years we get none.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In 2022 we caught just one Canada Warbler (adult male above), bringing our 41-year total to 35. The record is five in one year.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Migrant Kentucky Warblers come through Hilton Pond Center in nearly equal numbers in spring (11 bandings) and fall (13). We captured two autumn immatures in 2022.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Nashville Warbler is another of those species for which we've banded just nine individuals since 1982--eight in fall migration (including one this year). Below are some snapshots of several other "uncommon" species banded at Hilton Pond Center in 2022.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center This year we banded one adult male Baltimore Oriole (above), just our ninth-ever for this colorful blackbird species. BAOR breed more commonly just north of York County and are increasingly spending the winter in the South Carolina Midlands.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A third-year Sharp-shinned Hawk (above) banded in February 2022 was our 42nd since 1982. Most (74%) have been immatures banded October through December. Although Cooper's Hawks are present year-round at Hilton Pond, sharpies are primarily winter residents; they rarely breed in South Carolina.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We banded three Brown-headed Nuthatches this year, bringing the species total to 59. This species was more common locally before a neighboring farmer harvested 45 acres of mature Loblolly Pines.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Even less common at the Center are year-round resident White-breasted Nuthatches (female above). One banded this year brought the species total to 34. (We had hoped for visits by elusive Red-breasted Nuthatch migrants from up north in 2022 but none appeared.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We seldom actually see Winter Wrens at Hilton Pond Center, so we'd likely not know they are here without running mist nets on warm winter days. We caught one WIWR in mid-October 2022, bringing our 41-year total to 18. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center •• 2022 FOREIGN ENCOUNTERS •• Northern Cardinals, Carolina Chickadees, Tufted Titmice, Carolina Wrens, and Mourning Doves, among others, are year-round residents at Hilton Pond Center. We recapture many of them over and over again after banding--"trap junkies," if you will. Other species are non-residents that migrate away after the banding season, never to be seen again, while a few return in one or more later seasons as excellent examples of precise site fidelity. Others show up far away and are encountered by banders or other citizens who report them to the U.S. federal Bird Banding Laboratory clearinghouse in Laurel MD.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our furthest known flier to date was a brown Purple Finch (PUFI file photo above) of unknown age banded at the Center in Feb 2004 and encountered two months later at Monastery, Nova Scotia--where it had been killed by a cat. This was a sad way to end a northbound migration route that covered at least 1,275 straight-line air miles. Despite banding 77,065 birds during 41 years at Hilton Pond Center, only 70 individuals (14 species) have been encountered outside our home county of York SC, while an additional 46 (13 species) were reported from within the county. (Click on either link to review each list in a new browser window.) We speculate such low foreign encounter rates are due in part to a relative scarcity of banders in the southeastern U.S. and because of the mostly rural nature of the Carolinas; fewer banders, fewer people, and large swaths of undeveloped land mean banded birds are less likely to be encountered. Reports of birds banded here at the Center and encountered elsewhere are indeed rare, but even more uncommon are individuals banded by someone else and recaptured at Hilton Pond. This has happened just ten times in 41 years.

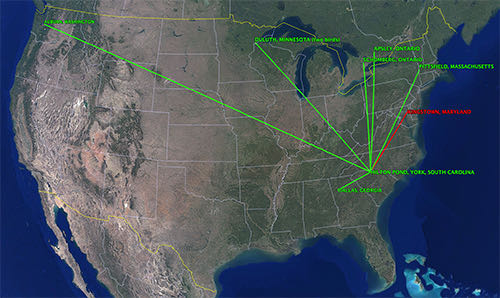

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Of particular note among long-distance migrants are several Pine Siskins (above) that showed up elsewhere after being banded at the Center. Green lines on the map below show the theoretical straight-line paths of PISI that were encountered north and west of the Center, and one "oddball" that wandered off to Georgia. (The red line from Kingstown MD is a PISI banded there that we recaptured at Hilton Pond.) All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The adventuresome siskin in Auburn WA was banded in March 2021 at Hilton Pond and found dead in December that year; up to that time it was our furthest foreign encounter at 2,263 straight-line miles away from its South Carolina banding site! All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We were enthralled already by this long-distance traveler but in June 2022 got word a second siskin had been recovered close to the site of the first one. This newest PISI (banded March 2021) was found at Anacortes WA (see map above)--about 2,297 straight-line air miles from the Center and 34 miles further away than the previous PISI at Auburn. This about as far west in the contiguous U.S. a land bird can fly. Amazing stuff! Our second "Report to Bander" from the Bird Banding Lab this year was for a House Finch (adult male below)--the species for which we've had more foreign encounters than any other. But first, some deep background:

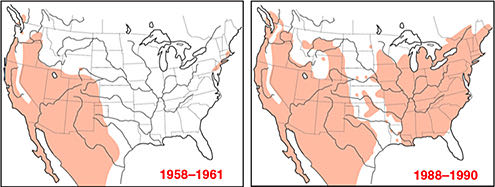

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Here in the Carolinas, House Finches are among the most abundant feeder birds--and not just in winter. However, this has NOT always been the case in the eastern United States; i.e., HOFI were common out west but are not historically native east of the Great Plains. That all changed in the early 1940s when pet shop owners on Long Island NY released a few dozen pairs of illegally marketed "Hollywood Finches." (The map at left below shows the historical range of House Finches; at right is the current distribution through 1990; the gap in the Midwest is much narrower now.)

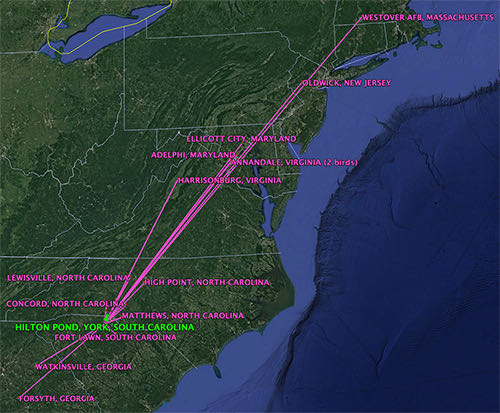

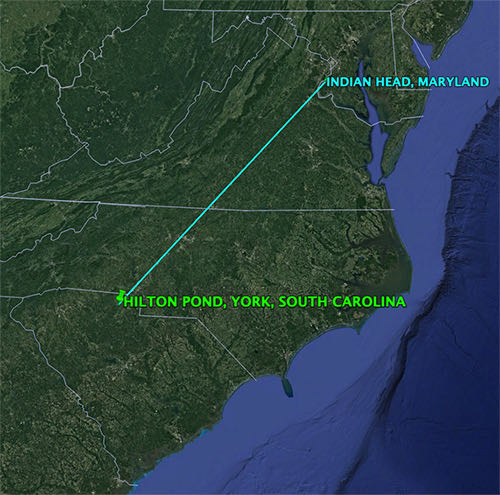

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center These HOFI became the nucleus for a population that in less than fifty years spread north, south, and west to become the common backyard bird we see across the eastern half of the continental U.S. In the early 1980s we had Hilton Pond House Finches just in winter, but these days if you hang a flower basket here or many other places in the East you're likely to get nesting HOFI. They have conquered the continental U.S. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In those early years, we had numerous winter-banded House Finches show up later at foreign locales, and nearly all those were north of Hilton Pond (see map above). After 1990, however, none of our banded HOFI were reported elsewhere. Since we were now banding House Finches in about equal numbers during all four seasons, we hypothesized northern-breeding HOFI were no longer migrating south in winter and that all HOFI at Hilton Pond were locally produced year-round residents. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We had to throw out that 30-year-old hypothesis this summer when we learned a male House Finch we banded as an after-hatch-year adult at Hilton Pond Center in February 2019 was found dead August 2022 at Indian Head MD (see map above). This particular bird, of course, is just one data point, but it does document one more adult male House Finch we caught in South Carolina in mid-winter was found found three years later during the breeding season--336 miles to the north. This sure looks like it could still be seasonal migration and--if it's not just a bird wandering about--it does invalidate our hypothesis that all HOFI at Hilton Pond these days are year-round residents AND that none of them migrate any more.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center So, was this House Finch behavior a fluke, or are there other migrant HOFI at winter feeders in the Carolinas? One way to get answers is for folks to keep on banding House Finches and tracking and reporting them across their eastern range--something we fully intend to help with through our long-term year-round bird banding program at Hilton Pond Center. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center •• 2022 RETURNS & RECAPTURES •• As noted, each year at Hilton Pond Center we recapture hundreds of birds we banded here previously. Some year-round resident birds like Carolina Chickadees are re-trapped on almost a daily basis--a good sign they are not "traumatized" by the banding experience. Other birds such as migrant finches may get banded one year and not be encountered again until they return years later. In 2022 we had several returns/recaptures worth mentioning. (Returns of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds are discussed in a later section.) All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

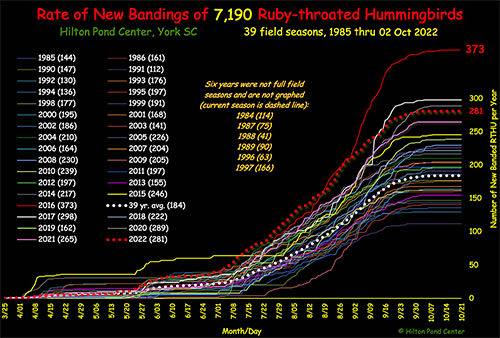

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center •• 2022 RUBY-THROATED HUMMINGBIRDS•• All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Ruby-throated Hummingbirds appeared in good numbers in 2022 at Hilton Pond Center (see chart above). For the 24th time we exceeded 200 annual bandings and had our fourth-most-productive season with 281--finishing well above our 39-year average of 184. This gave us a total of 7,190 RTHU bandings, about 9.3% of all birds banded at the Center. (NOTE: Because of special federal permit requirements, our RTHU research did not commence until July 1984--two years after other local banding activities began. Thus, 2022 was our 39th study season for hummers, versus 41 for other species.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our first Ruby-throated Hummingbird of 2022 appeared on 30 March--an adult male (above) arriving a few days later than our earliest date ever (27 March, in four different years). This year's earliest returning hummer was a banded adult female male on 31 March, although we did not catch any unbanded females until a rather late date of 2 May. The first young ruby-throat on 4 June was the Center's earliest-ever fledgling by five days; an immature female was banded the next day. The moral of this story is we begin stocking multiple sugar water feeders by St. Patrick's Day (17 March) for early migrants--although we do maintain a few feeders all winter in hopeful anticipation of western vagrant hummingbirds that rarely appear.

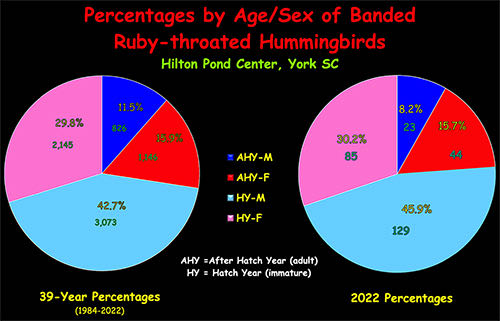

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center NOTE: To justify our policy of providing year-round sugar water feeders, we'll mention we've captured two vagrant Rufous Hummingbirds at Hilton Pond Center: An early hatch-year male on 23 September 2002 and a hatch-year female on 20 November 2001. The latter (above) was re-trapped and released in Columbus OH on 29 November the following year! All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center But back to Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. The 2022 season started rather slowly--its progress is marked by the red dashed line on the chart above--with only five RTHU banded by the end of April. This was a typical number for late April, although by then in 2014 and 2015 we had banded 31 and 36, respectively. This year things began to pick up in mid-May and bandings were well above average by date through all of June, after which banding really took off. For the next six weeks we were well ahead of any previous banding rate, and through the first week in September the parade of new Ruby-throats continued at a near-record pace. Alas, banding petered out by mid-September and we got no final rush of RTHU later that month. The last RTHU banding was a young male on 2 October. Despite the early fall slowdown, we did end up with our fourth-best tally of 281 RTHU bandings in 2022. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center By the end of any given breeding season at Hilton Pond Center we typically expect many more hatch-year RTHU among our banded birds. During 39 years (left pie chart, above), 72.5% of all ruby-throats banded have been recent fledglings (males in pale blue, females in pink); in 2022 (right pie chart) they made up significantly more at 76.1%. Our 129 hatch year males comprised nearly half (45.9%) of all bandings in 2022--above the 39-year average of 42.7%; by comparison, 85 young females resulted in only a slightly higher percentage (30.2%) than average (29.8%). Percentages for 23 adult males in 2022 (8.2%; dark blue on pie charts) were noticeably lower in 2021 than the 39-year average of 11.5%, while 44 females (15.7%; in red) were very close to the average of 15.9%. In short, adult males were considerably fewer than expected--our all-time high for them was 60 in 2015.

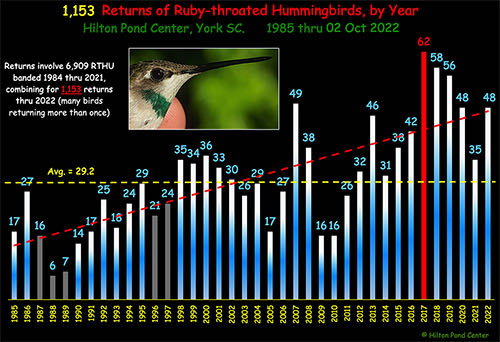

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of the most fulfilling things about working with Ruby-throated Hummingbirds is putting bands on their legs and seeing them come right back to Hilton Pond in later years, having traveled perhaps 1,500 miles one way to Central America--and then back. Even after nearly four decades, we are amazed how a creature that weighs half as much as a nickel can be successful at such long-distance migration. That's why we were pleased with 48 RTHU returns in 2022 (see chart above)--tied for our fifth best total and a nice rebound from last year. With 6,909 hummers banded at the Center through 2021, this season's returnees brought our 39-year total to 1,153. That number actually involves 793 individuals, since many ruby-throats like the adult female below returned in more than one later year. (NOTE: The dotted red trend line on the chart above shows RTHU returns are generally increasing at the Center--to be expected because our numbers of new bandings are also on the rise. We can't determine whether actual survivability is improving.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A quick calculation shows 793 of 6,090 is a return rate of 11.48%, which at first blush seems quite low. However, when one considers an estimated 60-80% of each year's young hummers fail to make it through their first winter, 11% survival and eventual return to Hilton Pond Center is pretty substantial--plus it's likely some RTHU return here and are not recaptured. Ruby-throated Hummingbirds do indeed have a high die-off, what with the dangers of migration, predators (natural and otherwise), window strikes, disease, bad weather, genetic deficiencies, and other factors, so we're very pleased with our overall 11% return rate.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Of the Center's 48 RTHU returns in 2022 (see Table 1 just below), 30 were banded last year (2021), seven in 2020, four in 2019, two in 2018, two in 2017, and two in 2016. Of those, 18 were males, 30 females. TABLE 1: #42890--08/14/16--7th year female (16,17,18,19,20,21,22)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Perhaps the most striking aspect of the list above: Among 35 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds returning to Hilton Pond Center in 2022 only 18 were males (adult above)--and 15 of those were banded just last year. The oldest male (#08923) is in only this third year. This dearth of returning males is difficult to explain, but we have considered three possibilities below, the second of which we believe is most likely. (We're happy to entertain other hypotheses. If you have one, please click here to send an e-mail to us at INFO.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One final note about the Center's Ruby-throated Hummingbird returns in 2022: Only two had been banded in September and none in October during previous years--a phenomenon that happens regularly at the Hilton Pond. We suspect this is because the vast majority of late-summer bandings are young birds that very well may be pass-through migrants from points further north. If these pass-through individuals--including the hatch-year male pictured above with partial red gorget--survive their first southbound migration, they may return to some distant natal range rather than to Hilton Pond. It's also possible many September/October bandings are late-fledging, late-departing youngsters that aren't as strong and well-developed as RTHU that had been around all summer; as a result, they simply don't make it through their first migration south. (Again, we welcome alternate hypotheses on this situation at INFO.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Please note that all Ruby-throated Hummingbirds captured--or recaptured--at Hilton Pond Center are banded and then marked with temporary, non-toxic green dye on lower throat (see adult female above). This helps us avoid recapturing "trap junkie" hummers that re-enter our pull-string and electronic traps over and over and over again. Come spring it also means folks north of us can be alert for color-marked RTHU from the Center; in autumn observers to our south can be on the lookout. If you see ANY color-marked hummingbird, please report it to us immediately via e-mail at RESEARCH; a photo would be most helpful.

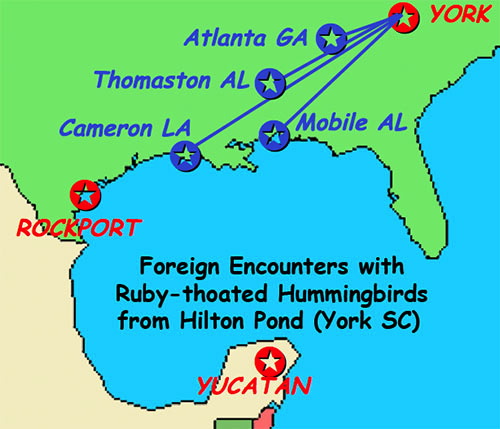

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Alas, only six of our Hilton Pond hummers have been seen elsewhere, and most were reported because they were color-marked. Four RTHU were encountered during fall migration (see map above) in Atlanta, Louisiana, and Alabama (two individuals). Two spring migrants were reported from Massachusetts and Clover SC (the latter about ten miles north of the Center). All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center •• 2022 "YARD LIST" & NESTING SPECIES •• Our inventory of birds observed through the years on, over, or from Hilton Pond Center rose by one to 173 last year, when we unexpectedly mist-netted that state record Broad-tailed Hummingbird. We had no new yard species in 2022 but did see or hear a total of 108 bird species at the Center--slightly below our record of 111 reached in 2020 and 2021. This year's tally represented more than half (62%) the species observed locally since 1982.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We find it interesting that of 38 North American Wood Warblers LIKELY to be seen at Hilton Pond Center, we have observed and banded 35 of them (including the male Black-throated Blue Warbler, above). The three missing species are Cerulean Warbler and Mourning Warbler--both of which typically migrate further inland west of the Center--plus the endangered Kirtland's Warbler. (The other 14 extant North American parulids are western species not likely to occur in South Carolina's Piedmont Province. Bachman's Warbler--now "officially" extinct from the Carolina Lowcountry and elsewhere--can no longer be seen except in museums.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Among all species encountered at the Center since 1982 we've found nests for 25, including other birds that often lay their eggs in a box intended for Eastern Bluebirds (winter male and female above). A male Prothonotary Warbler even tried building a nest in a box with 1.5" hole before a dominant bluebird pair drove him away. All our boxes have been fairly effective and have been used by Tufted Titmice, House Wrens, and Carolina Chickadees. We've also installed several boxes with 1" diameter holes that exclude bluebirds but allow Brown-headed Nuthatches to enter. Boxes stay up year-round and sometimes serve as roost sites during cold weather; they occasionally are occupied by Southern Flying Squirrels and once by a Golden Mouse.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We have six much-larger nest boxes mounted on posts in the water around Hilton Pond itself. Complete with predator baffles, these structures are designed for Wood Ducks (hen and young, above) and have produced more than 900 ducklings since 1982. Eight plastic gourds atop a tall pole beside the pier on Hilton Pond have been hanging for 30 years without a known visit from any coveted Purple Martins. The gourds have been occupied rarely by nesting pairs of Eastern Bluebirds and European Starlings. Also by lots and lots of paper wasps. NOTE: If you're not keeping a "Yard List" for your own property we encourage you to do so, and to report your sightings via eBird. The eBird Web site provides a great way for you to keep track of what you see and when, and it allows you to make valuable contributions to our body of knowledge about birds. You, too, can be an ornithological "citizen scientist." All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center •• 2022 CUMULATIVE BANDING RESULTS •• A complete list of 2,153 birds of 80 species banded at Hilton Pond Center in 2022 is in the table below. Also shown are our 41-year maximums and averages, plus grand totals for each species. We invite you to examine and dissect our data table below and narrative above for trends or to see whether we captured your favorite species. For a running account of banding and recapture results for the just-completed year, please refer to lists at the end of each installment of "This Week at Hilton Pond," beginning with 1-15 January 2022. There really is much to be said for long-term banding projects like ours that provide solid baseline data leading to better understanding of avian ecology. We're proud to report we've been at it since 1982 at Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History--still the most active year-round bird banding station in the Carolinas. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

PAYPAL & VENMO (funding@hiltonpond.org): Checks also can be sent to Hilton Pond Center at:1432 DeVinney Road York SC 29745 All contributions are tax-deductible on your TABLE 2: The list shows all 128 bird species banded locally since 1982;

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Don't forget to scroll down for lists of Hilton Pond supporters and of all birds banded and recaptured during the period. Photoshop image post-processing for this page employs |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Dr. Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

|

Marie Baumann, Ramona & Jim Edman, Gail & Tom Walder,

Marie Baumann, Ramona & Jim Edman, Gail & Tom Walder,

When we purchased our 11-acre plot in 1982 it was almost all open (pond is at left in photo at right), the result of a century of agriculture that apparently involved cattle grazing and planting row crops such as cotton, corn, tobacco, and soybeans. We're not farmers, and decided early on we would NOT spend our days--or waste time, energy, or resources--cutting 11 acres of grass. (Down With Lawns!) Thus, we allowed the land to "go fallow," mowing only a couple of small "meadows" and three-foot-wide, easily navigable nature trails that meander for nearly two-and-a-half miles around the property.

When we purchased our 11-acre plot in 1982 it was almost all open (pond is at left in photo at right), the result of a century of agriculture that apparently involved cattle grazing and planting row crops such as cotton, corn, tobacco, and soybeans. We're not farmers, and decided early on we would NOT spend our days--or waste time, energy, or resources--cutting 11 acres of grass. (Down With Lawns!) Thus, we allowed the land to "go fallow," mowing only a couple of small "meadows" and three-foot-wide, easily navigable nature trails that meander for nearly two-and-a-half miles around the property.

Oct 15 to Mar 15:

Oct 15 to Mar 15: