HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

|

- GENERAL ARTICLES - |

|

Hilton Jr., B. 1990. Telling nature's secrets . . . The interpretive naturalist at work. South Carolina Wildlife 37(5):12-15. (Note: The draft below was submitted to South Carolina Wildlife magazine; the article that actually appeared in print may have been edited.) |

When the phone rings at my house at Hilton Pond near York, I always hurry to answer it. More often than not, the person on the other end has news of unusual birds at a feeder, a thoughtful question about an unfamiliar wildflower, or interesting comments about other natural phenomena.

I've encouraged readers to write or phone me at home, and based upon hundreds of letters, cards, and calls I've received the past four years, I'd say lots of people these days are intensely interested in natural history. Not too long ago, it seemed such interest lagged, but suddenly folks have a renewed desire to understand what's happening in the world outside their windows. They yearn for knowledge, and often turn to interpretive naturalists to unravel nature's secrets.

From its earliest days as a British colony, South Carolina has either produced or attracted famous naturalists. Mark Catesby (immortalized in the species name of the American Bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana, as he painted it, below left), was one of the first trained field observers to travel the Palmetto State.  In 1722, he began at Charleston what has been called the original comprehensive natural history of the Southern colonies. Fifty years later, John Bartram--in some of the best-written prose of his day--described floral and faunal wonders of the Southeast for an incredulous and insatiable audience back in England. In 1722, he began at Charleston what has been called the original comprehensive natural history of the Southern colonies. Fifty years later, John Bartram--in some of the best-written prose of his day--described floral and faunal wonders of the Southeast for an incredulous and insatiable audience back in England.

In 1787, French botanist Andre' Michaux came to the Carolina backcountry and in Charleston established a nursery of native plants; the most exotic of these he sent back to France for horticultural and scientific purposes and to amaze his countrymen with the New World's botanical diversity. By 1831, John Audubon also visited Charleston to observe and collect several dozen of the birds he painted for his famous "Elephant Folio." In the port city, Audubon met Rev. John Bachman (below right), a Lutheran minister and founder of Newberry College. Bachman, whose sister-in-law painted backgrounds for Audubon's birds, was himself a first-rate amateur naturalist who was honored by having a warbler and sparrow named for him. Botanists William Bull and Thomas Walter, ornithologists Alexander Wilson and Arthur Wayne, herpetologist John Holbrook . . . the list of naturalists with Carolina connections goes on and on, and with good reason. After all, South Carolina's Coastal Plain, Sandhills, Piedmont, and Mountain regions and moist, temperate climate support one of the most diverse assemblages of plants and animals in North America. The state is haven to more than 4,500 species of vascular plants, 38 snake species, 19 turtles, 12 lizards, 32 salamanders, 30 frogs and toads, one crocodilian, more than 70 mammals, 380-plus birds, an estimated 500 spiders, several hundred thousand invertebrates from beetles to roundworms to jellyfish, and who knows how many species of previously unknown organisms just waiting to be discovered by curious and observant individuals. Where there's this much to study there will most certainly be naturalists--both professionals and laypeople who are interested in learning nature's secrets.

In the early days, South Carolina's economy was mostly agricultural. Nearly everyone spent at least part of his life on a farm, clearing the land and replacing native plants and animals with food crops and livestock. People then, it's been said, had more intimate relationships with nature. In need of different woods for heating and for furniture, farmers could identify dozens of tree species. They knew the ways of the white-tailed deer and cottontail rabbit that supplemented their winter larders, and they were greeted at dawn by many a bird whose song and plumage they recognized. Like Native Americans who occupied the land before them, settlers from Europe were in tune with their environment and understood--almost instinctively--the natural balance of which they were part. With the advent of urbanization and mechanized farming, many South Carolinians began losing touch with nature. In the first half of this century especially, people became tied to long hours inside offices and factories. Minimal leisure hours left them with little opportunity to investigate the out-of-doors. Children with time to spare still explored stream and wood, and there were formal natural history studies in universities, but the average layperson practically ceased observing nature's marvels. Then, in about 1960--perhaps fueled by Rachel Carson's exposure of pending environmental disasters in Silent Spring--there was a sudden rebirth of interest in natural history, an interest that hit its stride on Earth Day in 1970 and intensified in the 1980's. People became acutely aware they shared the earth with other organisms, and a new sense of responsibility began to develop. Such responsibility demanded that citizens acquire information to facilitate sound judgments about the environment, and people often turned to professional naturalists already immersed in studying the secrets of nature. There are several indicators of rapidly-increasing public curiosity in natural history. Nowadays, virtually every bookstore has a major section devoted to nature writings. Authors and publishers have made small fortunes on field guides to everything from birds to seashore life. State and national organizations publish magazines that describe in breathtaking prose and photograph the intricate web of life that unfolds for whomever chooses to look. And every day there are dozens of television programs about natural wonders--even cable channels that specialize almost entirely in telecasts about the environment. Indeed, more Americans are reading and viewing to learn about nature than at any time in history, but this doesn't seem to be quite enough to satisfy their quest for knowledge. What every "nature freak" really wants is to have his own naturalist, one who can "tell nature's secrets" in a detailed and personal way. There is a need for people who interpret nature's ways and pass on their findings, and South Carolina's modern-day naturalists are doing a great job meeting that need.

The Palmetto State's most famous contemporary naturalist is probably home-grown Rudy Mancke--Spartanburg native, Wofford College graduate, and former high school biology teacher who became curator of natural history at the South Carolina State Museum in Columbia.  Through the museum, Mancke (below left) spent countless days in the field amassing knowledge about South Carolina plants and animals, and he expended equally long hours sharing that knowledge with teachers, schoolkids, and the general public. In the mid-1970's, Mancke helped found the South Carolina Association of Naturalists (SCAN), an organization of professionals and laypeople who still criss-cross the state one weekend each month to learn something new about natural history locales. Through the museum, Mancke (below left) spent countless days in the field amassing knowledge about South Carolina plants and animals, and he expended equally long hours sharing that knowledge with teachers, schoolkids, and the general public. In the mid-1970's, Mancke helped found the South Carolina Association of Naturalists (SCAN), an organization of professionals and laypeople who still criss-cross the state one weekend each month to learn something new about natural history locales.

Mancke's effectiveness as a field trip leader is based upon two things--his knowledge and his enthusiasm. People who come to him with a natural history specimen usually receive accurate answers to their questions of "what is it" and "where'd it come from," but they often get a good dose of the philosophical if they dare ask "what good is it." Having spent considerable time afield with Rudy Mancke, I can confirm he has been an infectious agent in the epidemic of interest in natural history, especially by sharing his expertise statewide and nationally through South Carolina ETV's broadcasts of "NatureScene." That tens of thousands of people will sit still on Saturday evening for 30 minutes of low-key footage of a man taking a field trip is witness that there is indeed widespread fascination for the natural world. Two of Mancke's common themes are "little things in nature are important" and "you don't have to go far to see powerful stuff right here in South Carolina." Although his "NatureScene" shows have included footage from across the U.S., Mancke brags about the wonders of his home state and says he's pleased so many fellow Carolinians are developing "pride in place" and "love of local country and its natural heritage." "Curiosity is innate and was always tied to survival," claims Mancke. "Today we shield ourselves from our surroundings, and our survival skills aren't as necessary as they were in our evolutionary history. When three meals a day are guaranteed, we can spend more time looking at nature and writing poetry about it. I'm lucky because I've been able to help so many people look and understand."

Steve Bennett, whose new book South Carolina: The Natural Heritage (Univ. of S.C. Press, 1989) contains impressive color photos of the state's wonders, is with the Nongame and Heritage Trust Program in Columbia. As a sub-unit of S.C. Wildlife and Marine Resources, the Heritage Trust inventories and oversees rare or endangered habitats and organisms in the state and works toward their preservation. Although Heritage Trust has no formal nature education program, Bennett and his co-workers are frequently called upon to interpret specific aspects of our natural world. "Most people who have an outdoors experience," Bennett says, "fall into one of two categories. They are either struck by some piece of natural beauty--a colorful butterfly, for example--and go no further than just looking, or they are frightened or threatened by something they encounter and don't understand--such as a snake or a bear. In both cases, these people simply aren't inquiring beyond the surface information of a given event, and that's where interpretive naturalists come in. It's our job to explain both form and function within nature, to talk about the butterfly as pollinator, the snake as natural predator." Like other naturalists, Bennett is asked often for ultimate explanations for natural happenings. "Although we try to explain things as best we can, we also need to let people know naturalists don't have all the answers. We don't understand all the functions an organism might have in the natural scheme, and that's the best reason I can think of for everyone trying to interpret their surroundings. If we don't comprehend today the role an organism plays in the ecosystem, we'll never have an opportunity tomorrow to discover that role when the organism or the habitat has been destroyed. It's very important that people go beyond the superficial to learn some details of how everything fits together, and the naturalist can help a lot with that."

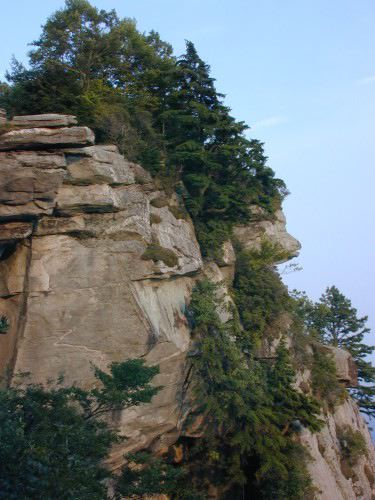

In 1984, Caesars Head (below right) became the first South Carolina state park with a full-time naturalist. Today, 17 state-owned parks have full-time interpreters or interpretive naturalists on staff, and there are ten additional "park interpreters" during summer months.  Nine of the permanent positions were created in the past two years--an indication of the state's increasing emphasis on having park staff who can help the public discover and understand a park's natural aspects. Nine of the permanent positions were created in the past two years--an indication of the state's increasing emphasis on having park staff who can help the public discover and understand a park's natural aspects.

Joe Watson, head naturalist for South Carolina's Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism, says his staff's role is to "give the public an appreciation for nature, for all sorts of outdoor activities, and for our state's impressive parks. Our philosophy is that, if we can get people out to look at things in nature, they will begin to learn even more on their own. To that end, our naturalists try to develop a broad-brush approach to interpretation, not weighing the public down with details of indentification and classification, but talking about ecosystems, about why things grow where they do, about the relationships between plants and animals." After attending state park meetings around the U.S., Watson is convinced South Carolina's park system is "among the best in the nation. From all I've seen, our renewed commitment to nature interpretation is what our citizens want and need. Even as our state park system began in the 1930's, we had programs in nature education. The parks hired schoolteachers during the summer to do nature interpretation, and this tradition continued until halted by World War II. Not much happened in the 1950's, but in the late sixties public interest began to grow. Today we've had a new beginning with visions of naturalists in all the state parks. We have a relatively small staff, but it does a very good job helping visitors appreciate what South Carolina has to offer in the realm of natural history." Naturalists usually start in as beginners who have had their curiosity aroused about nature. Some start very young; others not until late in life. Age does not matter in a naturalist; it is the spirit that counts.--Vinson Brown (in The Amateur Naturalist's Handbook) I spent four years in Minnesota studying behavioral ecology of Blue Jays (below left), and even though my graduate work was with birds, I resist being labelled an ornithologist.  I'd much rather be thought of as a "naturalist" who examines natural occurrences in diverse fields of study. I share that philosophy with an increasing number of scientists, an outlook I believe is important if we are to understand the big environmental picture as well as the details of particular scientific fields. I'd much rather be thought of as a "naturalist" who examines natural occurrences in diverse fields of study. I share that philosophy with an increasing number of scientists, an outlook I believe is important if we are to understand the big environmental picture as well as the details of particular scientific fields.

There are two other things I know I have in common with Rudy Mancke, Steve Bennett, Joe Watson, and many others who call themselves "naturalists." For one, I take almost giddy delight in learning every new natural history fact I stumble on. For the other, I get even greater joy from sharing that knowledge with other people. I don't think I've ever met a naturalist who doesn't feel that way, who doesn't lead field trips and give lectures and answer the "same old questions" with constant zeal. It's our calling that we spread the word to students, teachers, and the general public, that we stress the importance of trying to comprehend all parts of the natural scheme. Yes, we naturalists are an excitable bunch, and we never tire of folks writing or calling with comments that help us all in "telling nature's secrets." We're just grateful so many people are taking an interest in the natural world we love. Bill Hilton Jr. is a science education consultant, writer, naturalist, and Macintosh computer enthusiast who lives in York, South Carolina. |

Since 1986, I've written a newspaper column entitled "The Piedmont Naturalist," a weekly account of some occurrence in nature that piqued my interest, be it the beauty of broomsedge in winter, a migrant bird I've just banded, or why it's important NOT to cut down dead trees that could serve as woodpecker condominiums.

Since 1986, I've written a newspaper column entitled "The Piedmont Naturalist," a weekly account of some occurrence in nature that piqued my interest, be it the beauty of broomsedge in winter, a migrant bird I've just banded, or why it's important NOT to cut down dead trees that could serve as woodpecker condominiums. That Bachman wrote the text for Audubon's "other" folio on North America's quadruped mammals further reveals his broad grasp of natural history

That Bachman wrote the text for Audubon's "other" folio on North America's quadruped mammals further reveals his broad grasp of natural history