|

|

|||

|

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND |

|

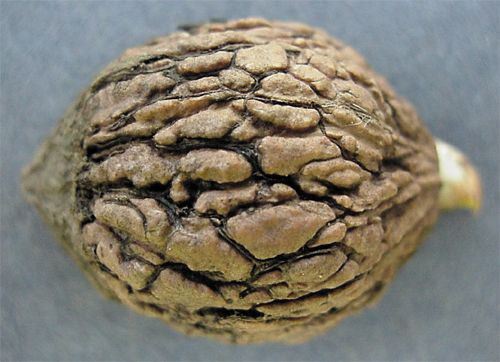

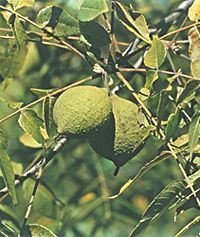

In front of the old farmhouse at Hilton Pond Center is a flagstone sidewalk that yielded an unexpected nature lesson this week. Stimulated by warm weather and recent spring rains, several tree seedlings had emerged between the stones, and--lest they eventually block the walkway--we removed them while they were still small enough to pull. The sprouts had compound leaves and we were pretty sure of their species--but we hardly anticipated having our identification confirmed in an interesting way.  As we tugged on one seedling that was about a foot tall, it slid from the earth and brought with it what at first looked like a large chunk of soil (below left). Black Walnuts, Juglans nigra, are truly tough nuts to crack. Their shells--far thicker than those of the English Walnuts used in cookies and other baked goods-- practically require a large mallet or small explosive to open, and the nutmeat is so small it's almost not worth the effort. Nonetheless, Gray Squirrels and other rodents--even Beavers--use their sharp incisors to get inside the nut, and Red-bellied Woodpeckers hammer away incessantly until the nutmeat is revealed. Even Wild Turkeys reportedly make use of the walnut, since their powerful, grit-filled gizzards can eventually grind down the hard shell. Knowing how hard it is for animals to open a Black Walnut, we've always been intrigued that a tree could ever grow out of one, By late summer, the Black Walnut tree produces large green fruits that ripen and fall to the ground (right). These are covered by of an oily husk that can discolor the skin on your hands and that was once used to make dyes and walnut stain for wood finishing. Squirrels gather the fallen fruits and nibble away the husk, revealing the nut within. A hungry squirrel may eat the nut on the spot, but more often it follows its instincts and buries the walnut in some special location--including spaces between flagstones at the Center. If a squirrel forgets its cache, the walnut lies dormant all winter, barely metabolizing and waiting its chance.

Two seed halves and paired cotyledons (below) make Black Walnut a member of the Dicotyledoneae--"dicot" for short--one of the two major subgroups of the Angiospermae (flowering plants). Dicots include all the hardwood trees and shrubs and many familiar wildflowers and ornamentals, both native and exotic; their flower parts are typically in fours or fives or multiples of these numbers.   Monocots--the other angiosperm subgroup--have only one cotyledon and are represented by, among others, yuccas, palms, sedges, and grasses (including bamboo and many important food plants such as corn and wheat). Monocots typically have flower parts in threes or multiples thereof and include, for example, the trilliums, lilies, and terrestrial orchids. (Coniferous trees and shrubs--pines, cedars, and cypresses--are in the Gymnospermae and have reproductive cones and seeds that are very different from the flowers found in angiosperms.) Black Walnuts occur in moderate numbers nearly everywhere in the U.S. east of the Great Plains, except for New England and south Florida. They grow to 90 feet in height with long, straight trunks up to a yard in diameter; Black Walnut is one of the most prized--and most expensive--woods in North America, so much so that roving bands of walnut rustlers have been known to cut down and steal mature walnut trees from public land; Here at Hilton Pond Center we're fortunate to have several walnut trees of seed-bearing size, and--since we carefully transplanted the vigorous seedling that we uprooted from between the flagstones--someday we'll have at least one more of these giant dicots to cast shade, make walnuts, and feed our ever-hungry Gray Squirrels.

If you enjoy "This Week at Hilton Pond," please help Support Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. It's painless, and YOU can make a difference! You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. |

Only when we hit the clod against our boot did we realize it was actually part of the plant. We had guessed the tiny tree growing in the wrong place was a Black Walnut; the lump attached to the root was the walnut itself, which nicely verified our guess.

Only when we hit the clod against our boot did we realize it was actually part of the plant. We had guessed the tiny tree growing in the wrong place was a Black Walnut; the lump attached to the root was the walnut itself, which nicely verified our guess. but the seedling we pulled up at Hilton Pond Center revealed how the process works.

but the seedling we pulled up at Hilton Pond Center revealed how the process works. When spring rains come and temperatures rise, the walnut absorbs moisture and the tiny embryo inside the shell begins to grow; this combination of internal hydraulic pressure and cell division yields a very powerful force--one so strong that it cracks open the walnut. At the same time, the energy stored in the nutmeat is tapped and a tiny root (hypocotyl) emerges and grows downward. Shortly thereafter, the walnut's two seed leaves (cotyledons) give rise to a stem that bears true leaves. Even though it was a week old and already a foot tall, the walnut seedling we uprooted at the Center had barely begun to consume the nutrient-rich nutmeat, and the seedling's new ability to use its leaves for photosynthesis probably meant the surplus would never be used completely.

When spring rains come and temperatures rise, the walnut absorbs moisture and the tiny embryo inside the shell begins to grow; this combination of internal hydraulic pressure and cell division yields a very powerful force--one so strong that it cracks open the walnut. At the same time, the energy stored in the nutmeat is tapped and a tiny root (hypocotyl) emerges and grows downward. Shortly thereafter, the walnut's two seed leaves (cotyledons) give rise to a stem that bears true leaves. Even though it was a week old and already a foot tall, the walnut seedling we uprooted at the Center had barely begun to consume the nutrient-rich nutmeat, and the seedling's new ability to use its leaves for photosynthesis probably meant the surplus would never be used completely. the black or dark gray bark is deeply marked with furrows and ridges that take on a blocky appearance in mature trees. Each compound leaf--up to 18" in length--is composed of 11-23 finely serrated, yellowish-green, aromatic leaflets that are smooth on top and very slightly fuzzy beneath. (The photo at right is of an immature leaf from a young seedling.) Black Walnut trees often stand alone in the forest--with no understory trees or shrubs beneath them--possibly because their roots and dead leaves produce juglone, a toxic chemical that can kill other vegetation.

the black or dark gray bark is deeply marked with furrows and ridges that take on a blocky appearance in mature trees. Each compound leaf--up to 18" in length--is composed of 11-23 finely serrated, yellowish-green, aromatic leaflets that are smooth on top and very slightly fuzzy beneath. (The photo at right is of an immature leaf from a young seedling.) Black Walnut trees often stand alone in the forest--with no understory trees or shrubs beneath them--possibly because their roots and dead leaves produce juglone, a toxic chemical that can kill other vegetation. some thieves go so far as to use large helicopters to airlift their loot after dark. Walnut logs are sold to sawmills, and the hard, finely grained wood is turned into furniture, gunstocks, veneer, bowls, carvings, and other objets d'art.

some thieves go so far as to use large helicopters to airlift their loot after dark. Walnut logs are sold to sawmills, and the hard, finely grained wood is turned into furniture, gunstocks, veneer, bowls, carvings, and other objets d'art.