|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

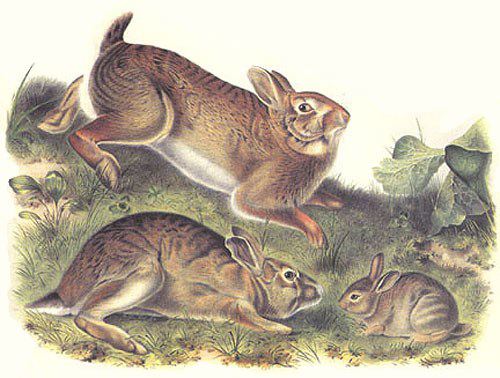

WASCALLY WABBIT Near the end of March we spotted a just-hatched brood of Wood Ducklings on Hilton Pond, and in further keeping with the spring holiday season it seems appropriate that this week we encountered a couple of what cartoon character Elmer Fudd refers to as "wascally wabbits"--those being, in our case, Eastern Cottontails. This native rabbit species is one that not only survived the coming of Europeans with their firearms, plows, and cross-cut saws, but seems to have flourished in close proximity to humans and serves as a reminder of Easter festivities.  All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We see Eastern Cottontails only occasionally around Hilton Pond, but more frequently now than when we first moved to the Center in 1982. In those days, the land was almost completely open, with scarcely a hiding spot for rabbits; now there are enough "brier patches" to support at least a few families on our 11 acres. For a time several years ago the observable rabbit population dropped to zero, likely because feral cats roamed the property and penetrated thickets in which our cottontails sought shelter and had litters. A recently established pair of Great Horned Owls seems to have exterminated the cats, but these nocturnal predators apparently haven't decimated the rabbits because the large-winged birds can't fly into brushpiles. The Eastern Cottontail takes its name, of course, from the bright white underside of its caudal appendage. Since the species tends to be rather solitary, we suspect this white flag is a distraction to potential predators rather than a signaling device for fellow bunnies. The Eastern Cottontail, Sylvilagus floridanus, is found in every county in North and South Carolina and occurs commonly across the U.S. east of the Rockies; it barely ranges into southern Manitoba and Quebec. In the Carolina Low County and southward Eastern Cottontails compete with the darker, smaller Marsh Rabbit, S. palustris, whose undertail is blue-gray undertail rather than white. The much less common New England Cottontail, S. transitionalis, bears a black spot between its shorter black-edged ears; it hides out in laurel thickets of the North Carolina mountains and northward along the Appalachians. For its body size, the Eastern Cottontail has exceptionally large eyes that protrude from the sides of its head (above left)--making it very hard to sneak up on from behind. (Despite their wariness, cottontails are successfully hunted in fall and winter throughout their range to provide meat for the larder.) The cottontail's long ears funnel sound and--with their rich network of blood vessels--radiate body heat during hot weather. This blood is also a magnet for ticks, and at Hilton Pond Center it's not unusual by midsummer to see an Eastern Cottontail with a whole colony of external parasites attached to one or both ears.  .. .. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although rabbits appear to have two big front incisors (above left), they are NOT rodents; Rodentia and Lagomorpha are separate orders. Rabbits actually have FOUR upper incisors, but two of them are peg-like and positioned behind the more obvious flat ones (above right). Our photo of a rabbit skull (below) depicts a side view of this unique dentition, as well as the animal's large eye sockets. It also shows fenestrations--literally "windows" in the bones of the snout--a delicate latticework that reduces the overall weight of the skull. This is a significant adaptation for an animal that spends much of its life bounding, leaping, and hopping.  All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Like most rabbits, Eastern Cottontails browse on low vegetation including grasses and forbs of many species; their teeth make a 45-degree cut that provides conclusive evidence against them when they raid your garden. The Hilton Pond cottontail illustrated on this page appears to have a preference for freshly opened leaves of Virginia Creeper and Quuen Anne's Lace (below right); the latter seems appropriate because it's also called "Wild Carrot." As green leafy matter diminishes with the onset of cold weather, a cottontail's diet shifts to bark, twigs, and terminal buds of shrubs and small trees. Despite its copious year-round consumption of vegetation, to consider the Eastern Cottontail an herbivore is a bit misleading. Since plant material is mostly cellulose, the rabbit has a problem; animals in general--including humans who use salads and cereals as "roughage"--are unable to digest this complex carbohydrate. In fact, a close look at dried "rabbit raisins"--the cottontail's spherical droppings (below left)--will reveal each is a compact mass of undigested plant fibers. Fortunately, the rabbit has several million very close friends--microbes that live within a caecal pouch of its intestine--and these unicellular organisms CAN digest some of the cellulose and turn it into simple sugars. Eastern Cottontails are primarily crepuscular (dusk- and dawn-active) or nocturnal, spending most of their daylight hours in brushpiles or beneath fallen logs; some individuals may dig burrows or occupy dens of other animals. There they nap, groom, and let microbes do their work, occasionally venturing out during the day in locations where predators are scarce. In the natural scheme adult rabbits are taken by Bobcats, Gray and Red Foxes, avian raptors, and weasels, while young are often eaten in the nest by Black Ratsnakes, Copperheads, and other large serpents. Huge numbers of cottontails are also killed by unnatural predators such as free-roaming cats and dogs and automobile tires. In the Carolinas, male Eastern Cottontails (bucks) are ready to breed by late winter and remain sexually active through the summer. Does come into heat at about the same time, depending on factors such as temperature, photoperiod, and the all-important emergence of green vegetation. When the buck spots a fertile female, he gives chase until the doe finally turns, faces him, and punches out with her forepaws. Then the prospective mates crouch until one suddenly leaps a few feet into the air, followed by a similar jump by the other. After repeating their leaps several times--perhaps as indicators of how healthy each rabbit is--copulation occurs.  Contrary to John James Audubon's idyllic rendering above, after mating the buck has nothing to do with female--or their offspring. Near the end of a month-long gestation period the doe builds a ground nest lined with fur and soft grasses. Her naked, blind babies weigh about an ounce at birth, but mother's milk helps them grow so rapidly they are furred and able to leave the nest after about two weeks. Weaning occurs at 21 days, and the siblings disperse at seven weeks. A healthy adult doe will produce 3-5 litters per year--more in the Deep South where the species may breed year-round--and since sexual maturity occurs at 2-3 months even young of the year have time to reproduce before the onset of winter. Eastern Cottontails are native meadow and woodland-edge mammals that have adapted to suburban--even urban--locales. Despite loss of natural habitats, their sharp vision, keen hearing, and natural camouflage help them survive and propagate in spite of human development. Last week at Hilton Pond Center a young student asked how a couple of our Eastern Cottontails could practically fade from view as she observed them moving toward the woods. We pondered the question and started to reply scientifically that cryptic coloration allows these "wascally wabbits" to blend with their backgrounds, but keeping in mind that spring holidays were upon us responded instead that "Everybody knows they disappear into thin air because they're Ether Bunnies." Happy Ether!

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

Comments or questions about this week's installment?

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond." (Please see Support if you'd like to make a gift of your own. You can also contribute by ordering an Operation RubyThroat T-shirt.)

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written & photographed You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use our on-line Hilton Pond Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to |

|

Make direct donations on-line via

Network for Good: |

|

|

Use your PayPal account

to make direct donations: |

|

|

If you like to shop on-line, you please become a member of iGive, through which more than 750 on-line stores from Barnes & Noble to Lands' End will donate a percentage of your purchase price in support of Hilton Pond Center and Operation RubyThroat. For every new member who signs up and makes an on-line purchase iGive will donate an ADDITIONAL $5 to the Center. Please sign up by going to the iGive Web site; more than 200 members have signed up to help. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. |

|

|

Participate in the |

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS WEEK * = New species for 2003 WEEKLY BANDING TOTAL 7 species 14 individuals YEARLY BANDING TOTAL (2003) 19 species 452 individuals BANDING GRAND TOTAL (since 28 June 1982) 123 species 42,566 individuals NOTABLE RECAPTURES THIS WEEK (with original banding date, sex, and current age) Carolina Chickadee (1) 03/29/02--after 2nd year male Northern Cardinal (1) 07/20/02--second year male Carolina Wren (1) 05/27/02--after 2nd year female White-throated Sparrow (1) 01/02/99--after 5th year unknown |

OTHER SIGHTINGS OF INTEREST  --On 12 Apr an Osprey literally dropped into Hilton Pond, grabbed a panfish, and took it to our big White Oak tree for a quick bite. We were able to squeeze off one exposure (above) with a fully extended 100-400mm telephoto zoom lens before the raptor flew off with its prey, perhaps taking advantage of the first non-rainy day of the week to head northward. |

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) Up to Top of Page Back to This Week at Hilton Pond Center Current Weather Conditions at Hilton Pond Center |

You can also post questions for The Piedmont Naturalist |

Join the |

Search Engine for |

|

|