|

|

|||

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND

22-30 November 2006

Installment #338---Visitor #

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week)

|

Only a few places remain for our upcoming |

|

Join Us for the |

|

|

GOCHISOSAMA, YAMAGATA:

A JAPANESE TRAVELOGUE

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center AN INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION Back in July 2006 we serendipitously came across a listserv announcement that Yamagata University in Japan was holding an international competition for proposals involving Nature and Human Symbiosis. Curious about this opportunity, we browsed the University's Web site and learned the school is north of Tokyo in Yamagata Prefecture.

Yamagata sounded like "our kind of place," so we investigated further. The University described its competition like this:

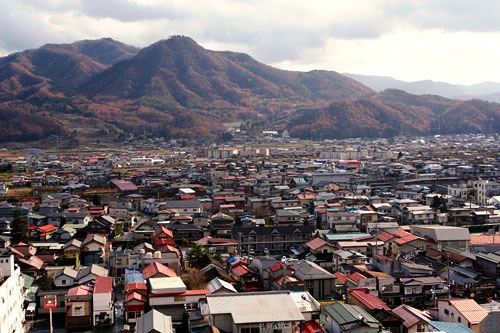

As long as it dealt with "Nature and Human Symbiosis," a proposed project could be in the realm of Education (including "university students, extracurricular activities, lifelong education, social education, cooperative education between high schools and universities, etc."), This all sounded like a nice opportunity to extend Hilton Pond Center's outreach all the way across the Pacific Ocean to Japan, so in mid-July we submitted a project in the competition. We proposed to work--from afar via the Internet--with students and teachers at the junior high school attached to Yamagata University, guiding them in how to make observations of the natural world. We wanted to outfit these students with digital cameras with which they could document plants, animals, and habitats in Yamagata, After sending off the proposal (in English) via E-mail in July, we got back an acknowledgement with a promise winners would be announced in late October, so we placed thoughts of Japan on the back burner and continued our summer hummingbird banding at Hilton Pond. As October came and went without news from Yamagata, we assumed decisions had been made and our proposal was not a winner, but on the morning of 5 November we noticed an E-mail from a Japanese address had entered our inbox. The message--in English--came from Dr. Joe Yamaguchi, a professor in Yamagata University's department of international studies, who informed us our proposal had indeed been awarded a Prize of Excellence in the "Nature and Human Symbiosis" competition! Dr. Yamaguchi further explained there had been 83 entries--71 from Japan and 11 from abroad--and the judges had decided to award a Grand Prize, two Prizes of Excellence, two Honorable Mentions, and a Special Recognition. The proposal winning the Grand Prize was to be implemented fully, but all six winners would receive transportation to Japan and lodging for an awards ceremony 29 November in Yamagata. We were so pleased by this honor that we scarcely hesitated in responding to Dr. Yamaguchi's invitation and immediately went on-line to find the best connections for the 8,000-mile trip to Japan. GOING TO JAPAN After a few more E-mails to and from Dr. Yamaguchi concerning various logistics, we finally decided on a flight beginning from Charlotte NC with a short layover in Atlanta; from there it would be 14 hours to Narita airport on the outskirts of Tokyo. Flying to Asia isn't as grueling as it once was, but 14 hours in a plane still isn't easy. One previous overseas flight took us on Quantas Air from San Francisco to Sydney, Australia--at 18 hours the longest non-stop commercial flight anywhere--so we figured a "mere 14 hours" to Japan would be a piece of cake. Arising at 4 a.m. on 29 November, we got to the Charlotte airport by 5:30 a.m. and breezed through security, departing at 7 a.m. and arriving 80 minutes later in Atlanta. Aside from losing ten hours and a full calendar day--the sun never set on our travels until after well after we got to Japan--the flight was actually pretty good: Window seat with no one beside us; nearly unlimited access to in-flight movies; personal iPod loaded with great jazz, big bands, and western swing; water and soft drinks ad libitum; plus two full meals and a snack en route. Best of all: No smoking on Delta flights to anywhere. Despite the inconvenience of having to climb over people during potty breaks, we always select a window seat to get an eagle's eye view of the terrain below. The perspective from 32,000 feet--where temperatures can be 90 degrees below zero--provided eye candy and food for thought as we cruised at more than 500 mph over one landmark or city after another. We had fond memories of some of these, having visited them on the ground: Nashville . . . Land Between the Lakes . . . St. Louis . . . and then Minot and Moose Jaw, where we'd never been. THE ARRIVAL Narita is a huge airport, but nicely laid-out. We got our baggage quickly and passed through immigration without a hitch before strolling into an open area where a four-foot banner inscribed "Bill Hilton Jr." told us we were in exactly the right place. Having completed the customary bows--and handshakes, since we had come from America--the welcoming crew grabbed all our bags and whisked us away to the president's car, mentioning our journey was not yet over. It seems Yamagata University was still about five hours away by road, and we needed to get moving so we could get to the hotel before too late in the evening . . . or morning . . . or whatever time our jet lag told us the time might be. After navigating the slow-moving Narita airport traffic, we finally started a long, gradual upgrade that took us toward the mountainous region around Yamagata Prefecture. It got pretty dark pretty fast, since winter days are pretty short at Yamagata City's 38th parallel--roughly as far north as Washington DC. In the darkness we could see little of the Japanese countryside, but near-continuous questions and answers between us and the Yamaguchis made the drive go faster. About an hour short of Yamagata hunger got the best of us, so we stopped for our first experience with how to slurp noodles dipped in broth--a perfectly acceptable Japanese mannerism that American mothers would scold us for. At 9 p.m. (Japan time) we finally arrived at Yamagata City and the Onuma Hotel, selected because it was only a block from the University. Thanks to the bilingual abilities of Joe and Yoshie, check-in went smoothly, and we bid good evening to our traveling companions as we boarded the elevator for a ride to the fifth floor. Our lodging was similar to a typical Western hotel: Twin beds, shower, standard toilet, TV (with nine local channels, plus pay movies), and a small refrigerator (with free bottled water). The big differences were the rooms were narrow, there was a short kimono robe and belt in a drawer, the toilet had a built-in bidet, and all the TV channels were in Japanese. (The only program we came close to understanding was a local equivalent of "Sesame Street"; we have trouble following "Desperate Housewives" in English, much less overdubbed in Japanese.) Surprisingly, even though Japan is even more techno-laden than the U.S. there was no Internet access, but there was one unexpected nice touch to our accommodations: The central portion of the mirror over the bathroom sink didn't fog up when we showered the next morning, so we could see to shave. Fatigued from our two flights and long drive from the airport, we crawled into bed at 10 p.m. Japan time, but our body knew full well it was really 8 a.m. in South Carolina and wasn't about to go to sleep--even though we'd been up for 28 hours. WEDNESDAY MORNING IN YAMAGATA Since we weren't sleeping anyway, we rose "early" at 7 a.m. for our first full day in Japan, discovered the fog-free mirror, dressed, and went down for breakfast alone in the hotel. We had no idea what the ethnic items on the Japanese-language menu might be, so we elected for an American-style meal of orange juice, scrambled eggs, ham, rolls, fruit, hot tea, and--surprisingly--a crisp garden salad. Our Japanese escorts weren't due to pick us up for a couple of hours, so we decided to grab our camera and take a short walk on the streets around the hotel. It was a gray morning with a little drizzle. Yoshie said Yamagata really has SIX seasons--the usual spring-summer-fall-winter, plus short rainy seasons between spring and summer, and again as fall turns to winter. Aside from an occasional bicyclist and a few road workers and trash collectors, the streets were deserted--Yamagata businesses don't seem to crank up until about 10 a.m.--so we simply strolled and drank in as much of our surroundings as we could. This was our first daylight view of Yamagata City, population 255,000, and we knew immediately we were in the midst of a culture very different from that of York, the Carolina Piedmont, or the USA.

As we walked, perhaps the first thing that struck us was Yamagata's architecture. Buildings were very close together, of course--most cities are very crowded in Japan--and the majority were only one or two stories tall. But the really remarkable thing was that these structures were functional AND beautiful, especially the roofs. Whereas in America we are careful to have very straight roof lines with flat hum-drum shingles, the tops of many Yamagata structures--especially the older ones--were definitely of East Asian design (above): Covered with three-dimensional ceramic or lead tiles, the topmost horizontal roof line had arcs at either end, and even the downslope of the roof was a gentle, pleasing curve. We also noticed buildings weren't the only functional things in Yamagata to be beautiful as well. Even stormwater ditches (left) were attractive to look at. In the U.S. roadside drains are typically fabricated from drab, gray concrete; those in Yamagata were lined with large, rounded stones, carefully placed. As water advanced down the culvert, it looked for all the world like a natural mountain brook--even more so because there were mosses, liverworts, and even ferns growing in the cracks between the rocks. We wouldn't be surprised to learn that salamaders and crayfish make a living in these imitation streams.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The next noticeable aspect of Yamagata City was all the vegetation. Almost everywhere we looked were perfectly pruned trees and shrubs (above). There were no vast expanses of green, but nearly every residence or business had at least a few square feet of garden. Even homes with no available earth had clay pots or concrete planters on the sidewalks out front. We recognized some of Yamagata's Asian plants because the same species are used as ornamentals across North America, especially Nandina, Burford Holly, Camellias, and Japanese Maple. There was also an assortment of pines shaped like bonsai trees, but full-sized. Outside numerous homes we saw containers with red peppers and various herbs, all undoubtedly destined for the cooking pot.

One of the strangest things about Yamagata gardens was that almost every evergreen tree had a stiff bamboo or wooden pole paralleling its main trunk. And even more strangely, each pole had varying lengths of rope descending from the pole top and tied to horizontal limbs on the tree beneath (above). This created a cone-shaped structure that puzzled us for a while. Many Japanese are Christians, so was this some sort of Yamagata version of a Christmas tree? It wasn't until later in the day when we aroused partly from our jet lag fog and realized what was going.

Quite a few Yamagata residences with large enough yards had a large Japanese Persimmon, Diospyros kaki--leafless and weighted down with spherical fruit (above). We recognized this tree because the dark orange 'simmons looked just like those on our Common Persimmon, D. virginiana, at Hilton Pond Center, only the ones in Yamagata were enormous--up to three inches in diameter compared to one inch for our native species.

We weren't the only observer who noticed pendulous persimmons around Yamagata. In fact, while we were preparing to take the persimmon photo above, a bird swooped in, landed on a branch, picked a big fat fruit, and flew with it to a neighboring roof. Needless to say, it would take a rather stout bird to make off with one of these steroidal 'simmons, and a sizeable bird it was: A Japanese Crow, AKA the Big-billed Crow, Corvus macrorhynchos (above). This species is noticeably larger than our American Crow, C. brachyrhynchos, and its bulging upper mandible makes it look more like a Common Raven, C. corax. The call of the Yamagata crows sounded to us like a deep but familiar "caw caw"; the Japanese hear it as an onomatopoeic karasu that is their name for the bird. Although crows do eat persimmons in Yamagata, they have to battle for the bounty with local residents who collect the fruits in late fall, thread a rope through them, and hang the strand from eaves of the house or some other handy spot (above right). This is a good thing to do with unripened persimmons because they're loaded with astringent compounds, and eating them too soon can pucker one's mouth almost inside-out. Ageing 'simmons diminishes the potency of bitter tannins and makes them more palatable. Incidentally, horticulturists have developed non-astringent varieties of the Japanese Persimmon, which is what one should seek when buying the tree for planting in the U.S. KAMINOYAMA CASTLE After watching the crow eat persimmons for a while, we eventually walked back to the hotel, arriving just before 10 a.m. for the rendezvous with our hosts. Joe had to teach and couldn't join us, but we had mentioned to him that we were interested in learning more about Samurai, the Japanese warrior class. (The Chinese character for Samurai is below left. Japanese people first adopted Chinese characters--each of which represents a complete word or concept--before they had their own written language;

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The existing castle (above), recreated from old architectural drawings, was built in 1982 to remind Kaminoyama residents about an important part of their history. (Today there are 47 refurbished or re-built castles throughout Japan, far less than the 3,000 or so that existed prior to about 1615.) The Kaminoyama Castle now houses collections of artifacts-- Kaminoyama Castle has a top-floor wrap-around balcony with a terrific view of the city and the closest mountain range (see photo at top of page). Exhibits at are rotated on a regular basis to encourage repeat visits by local residents, and the castle is home to many kinds of community celebrations during the year--including one that commemorates scarecrows and the tireless service they perform for farmers.

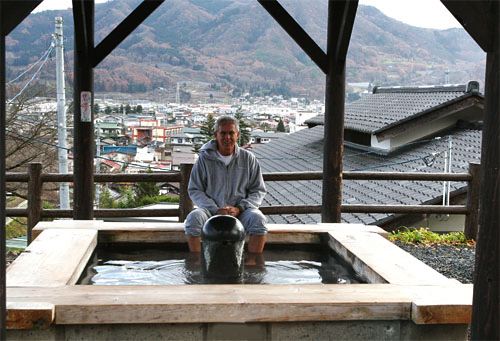

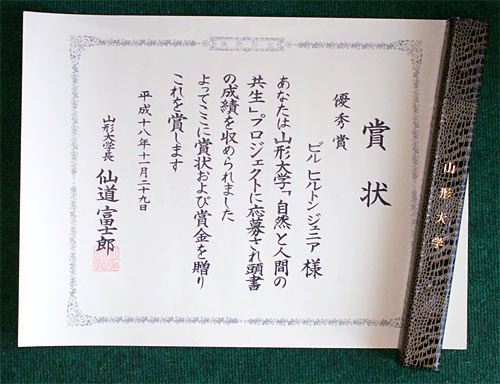

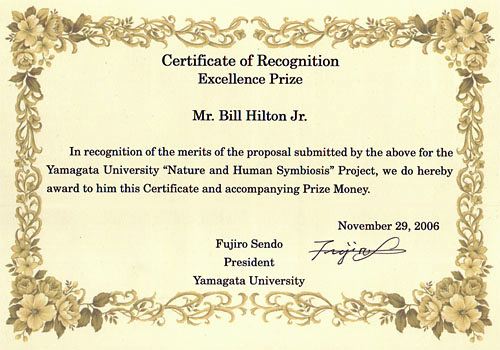

The city of Kaminoyama, at the foot of the mountains, is densely settled today after a long history of agriculture. The area is also famous for its volcanic hot springs, as we learned when Yoshie and Mr. Suzuki led us to a small roofed structure on the Kaminoyama Castle property. There we found our driver, wearing his usual sweater and necktie but with pantlegs rolled up to his knees; he was seated on a bench that allowed him to place his feet into a steaming pool of water, an ashiyu, or "footbath." Here hot springs are piped to the surface, and local folks and tourists often stop by for a therapeutic foot-dip in the mineral-laden waters. Yoshie explained that in winter, Japanese combat the cold by taking footbaths; as blood in their feet and lower legs is warmed, the heart pumps it elsewhere. We learned first-hand (above) this is a mighty effective process that didn't take long to bring us to a full-body sweat. According to Yoshie, this particular footbath was a "mild" temperature of 45 degrees Celsius (113 Fahrenheit), but it seemed far hotter to us. Since the water is high in mineral salts, crystals form around the edge of the pool--reputedly a sign the footbath has certain healing qualities. BUCKWHEAT NOODLES AND GOCHISOSAMA After working up a sweat at the footbath, it was back toward Yamagata for lunch. Yoshie and Mr. Suzuki has selected the finest noodle house in town for our dining pleasure, and it was there we had a real epiphany about Japanese culture. However, it wasn't the delicious buckwheat noodles served steaming . . . or the misu (soup) we dipped them in . . . or the tasty shrimp and eggplant tempura that struck us so deeply. "At the end of the meal," Yoshie explained, "we say gochisosama to thank the host, but we are also thanking those who prepared the meal. Furthermore, we are giving thanks to the farmer who grew the eggplant and the buckwheat from which the noodles were made, to the fishermen who caught the shrimp, even to the truck drivers who delivered everything to the restaurant. What a magnificent concept--one that immediately sunk deep into our psyche. For a lifetime we have been learning and teaching about ecology and nature's intricate interrelationships, often imploring our students to remember that "Everything is connected to everything else." Yoshie's gochisosama had that same ring of interconnectedness to it, and although we were fully aware that it takes the farmer (ivory carving at right) and the fisherman to feed us humans, we had never quite considered how even a simple meal of noodles and shrimp is an integral part of the whole. It's hard to explain exactly how or why this Japanese concept of gochisosama was so meaningful to us, but it already has caused us to look at every plate of food in a new and different way. MEETING THE PRESIDENT After lunch at the noodle house, we drove back to the hotel to change clothes; the sweatsuit we had on that morning simply wouldn't do for our first encounter with Dr. Fujiro Sendo, president of Yamagata University, who had requested a one-on-one meeting before the afternoon awards ceremony. AWARDS CEREMONY The Awards Ceremony for Yamagata University's "Nature and Human Symbiosis" international competition began sharply at 3 p.m. on 29 November in the ballroom of the Onuma Hotel. After a detailed explanation of how the competition started--it was the brainchild of Dr. Sendo--and how the proposals were judged, the University president called each recipient to the front to receive his or her prize money and an official 16" x 22" certificate beautifully rendered in Chinese characters (below). The other recipients were all Japanese citizens; as the only international winner we got a smaller certificate in English so we'd know what the larger one said. Dr. Sendo also presented us with an envelope containing ten crisp and clean 10,000 yen bills.

The Grand Prize winner was Dr. Mychio Dobashi, a Yamagata University professor whose project involves the somokoto of Yamagata Prefecture. As he explained during a PowerPoint presentation (below left), the somokoto are monuments, usually of native rock, placed in an area where nature has been disturbed to create a farm or other project. On each monument is inscribed a plea--usually in Chinese characters--for everyone to remember forever all the plants and animals displaced from the site or that gave their lives to the benefit humans. After Dr. Dobashi finished his talk, President Sendo asked us, as the only international winner, to address the audience. We learned through Yoshie's interpreting that Dr. Sendo and the rest of the university representatives were very pleased we had made the long trip from the U.S. to receive our award, THE RECEPTION (AND INVASIVE PLANTS) The reception following the ceremony was splendid, with a very impressive buffet of shrimp, sushi, and other Japanese finger food. We barely got to sample it, however, because several attendees wanted to ask us questions about everything from Native Americans' views on nature to the U.S. public education system to what it was like to hold a hummingbird. As soon as President Sendo finished his welcome (below), we were more than happy to reply to one-on-one queries, with Yoshie standing by to interpret when needed.

The woman in the dark suit near the center of the photo above is Ryoetsu Fujita, a clerk at Yamagata University who was the other winner of a 100,000 yen Prize of Excellence in the "Nature and Human Symbiosis" competition. Her proposal was to encourage University faculty and students to conduct studies on Mt. Gassan's virgin beech forests and unique complement of other plants and animals. The gentleman at right foreground is Shigeo Yamanaka, who received an Honorable Mention for his proposal to develop a seven-year high school and college program to foster environmental awareness. When we learned Shigeo was a high school horticulture teacher, we commented appreciatively about the nice plantings we had seen all over Yamagata City. We noted that many plants around town are also used as ornamentals in America, and this led to a discussion of our problems at Hilton Pond and elsewhere in the U.S. with invasive plants from Asia. Thanks to Yoshie, we were able to tell Shigeo about the scourge of Kudzu, which he called by its Japanese name, kuzu. At this point Shigeo coyly mentioned Japan has a problem with invasive plants, too, some of which come from America. When we asked for an example, he said the worst was Tall Goldenrod, Solidago canadensis--at which we nearly went into fits of despair, goldenrods being among our most favorite native North American wildflowers. After everyone had left the reception we went downstairs for supper in the hotel restaurant, where we tried to figure out the English-language menu that offered something like "packets of maritime organisms." (Turns out this was a sort of seafood gumbo.) A few hours we later crawled into bed--still jet-lagged and with sobering thoughts of "invasive" Tall Goldenrod mixed in with pleasant memories of a truly eventful day. TOURING YAMAGATA UNIVERSITY Our second full day in Japan started like the first: Rise early, eat an American-style breakfast in the hotel, then take a walkabout on nearby streets of Yamagata City. We dressed semi-formally again, and Yoshie and Mr. Suzuki picked us up at 10 a.m. for another visit to the University president's office. This time we met one-on-one with several of his vice presidents who had been at the previous day's awards ceremony. We were pleased and surprised to hear that even though our proposal for "An Eye on Nature in Yamagata" was not the Grand Prize winner and thus not selected for funding, there was sincere interest among University personnel in seeing our proposal implemented in some way. We said we were open to any ideas they had along those lines, up to and including a return trip to Japan at a later date. (We'll keep our fingers crossed.) One thing we noticed quickly on campus was the absence of cars; students at the University are not permitted to have automobiles, which explained the huge numbers of parked bicycles (left). But what do bicyclists do in bad weather, you might ask? Well, it rained on and off the whole time we were in Japan, and that didn't stop any riders. All bikes have fenders to prevent road spray, so the cyclist just grabs an umbrella and pedals onward. (We should mention their umbrellas are deeper than average--almost hemispherical--and transparent, so cyclists ride along dry as can be in a little plastic half-bubble.) On our campus tour we visited the International Student Center; there are no U.S. students today at Yamagata University, but through an arrangement with State University of New York the school will admit its first American next year. We also dropped by the campus store (where Mr. Suzuki graciously insisted on paying for a few small souvenirs for us to take back home) and toured a nicely curated small museum associated with the University library. Beautiful specimens of invertebrates, minerals, birds, ethnic artifacts, and other natural and cultural history objects were easily viewed in some of the cleanest, most orderly exhibit cases we've seen. MAPLE GARDEN & TEA HOUSE As we finished up at the University, Mr. Suzuki and Yoshie suggested we go to one of Yamagata's city-owned gardens--of which there are an unbelievable 207--all beautifully maintained by municipal gardeners.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Selected for our perusal was the 380-year-old Maple Garden (above)--named for its profusion of Japanese Maples; the site includes a tea house built on the site of an old Buddhist shrine. This small formal garden--only about acre in size--seemed much larger due to strategic placement of plantings that include a plethora of trees: a hundred species and 3,800 individuals. In one corner of the Maple Garden were three prize specimens of its signature plants: Japanese Maples, Acer palmatum (below). These particular trees were the largest of their species we've ever seen, since most we've encountered in the U.S. have been short, spindly ornamentals planted within the past 25 years or so. This is a slow-growing maple species, so we're not surprised a garden brochure says the trio is 320 years old; the brown metal sign to their right says they are to be protected in perpetuity.

As splendid as these old maples were, we were nearly as pleased by what was beneath them: A monoculture of soft, green moss (above) that carpeted the ground and even crept partway up the maple trunks. This is about as lush a growth of moss as one could hope for, and it makes us wonder why so many American homeowners complain about moss in their lawns. After admiring maples and mosses, we entered the tea house adjoining the garden. The manager asked if we'd like a personal tour and to participate in a formal tea ceremony. Having seen highlights of such events on TV and in the movies, we were eager to witness the entire ritual. THE SUSHI BAR After the tea ceremony, it was time to enjoy even more of Yamagata. Yoshie and Mr. Suzuki seemed pretty intent on showcasing aspects of Japanese life in which we had expressed interest. Since we mentioned in passing we wondered what REAL Japanese sushi tasted like, it was inevitable they would seek out a Yamagata sushi bar for our next lunch stop. We know lots of Americans who blanch at the thought of eating raw fish, but what sushi we've had in the U.S. has been pretty good. We'd always heard, however, that it can't compare to the "real thing" in Japan, absolutely fresh and prepared by real sushi chefs; after dining at the Yamagata establishment, we'll have to agree. YAMADERA TEMPLE With our bellies full of delicious sushi, it was time to travel again, so Yoshie and Mr. Suzuki asked the driver to head toward Yamadera ("mountain-temple"), a Yamagata suburb. We understood we were going to visit a temple, but the locale turned out to be far more than that. Yamadera, founded 860 A.D., includes a monastery and a whole complex of shrines; it is one of the holiest sites in northern Japan. Yamadera's popularity and importance were shown by the hundreds of people that walked through in the hour or so we were there--and by large bus and car lots that are filled many days during the year.

As we entered the grounds, the first shrine we came to was the main Buddhist temple (above). At foreground was a large cauldron in which incense burned to purify the area. At the top of the steps behind the pot was a six-foot-tall wooden carving of the happy Buddha, worn smooth by ten thousand hands rubbing its belly for good luck, and beyond the Buddha was a large gathering room with tatami mats. We removed our shoes and entered with permission of the monk seated nearby. Yoshie explained that beyond a translucent wall was a large lantern in which resided a flame brought originally from Kyoto and tended ever since by local monks--for nearly 1,200 years! Near the main Buddhist temple was a smaller Shinto shrine, which Yoshie said hailed back to days when Buddhism and Shintoism were closely intertwined.

Climbing all Yamadera's very steep steps turned out to be more of a challenge than one might think, and we all were winded and perspiring when we finally got to the shrine at the top. (Yoshie was very glad when we stopped to take photos, since it gave us opportunity to catch our breath.) Curiously, this topmost building (above) was primarily devoted to weddings; it's hard to imagine an entire wedding party ascending those thousand-plus steps for a ceremony of betrothal.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The whole mountainside at Yamadera was infused with history, spirituality, and natural beauty, and provided inspirational views of the surrounding countryside (above). There were countless stone markers embossed with the names of men and women who should not be forgotten, while magnificent tall old pine trees and native shrubs lining the path were living monuments to themselves and to nature as a whole.

As the sun set and the moon rose over this important religious complex (left), the rush of people that had ascended with us departed the mountain, and peaceful silence fell over the area. We quietly walked back down the 1,015 steps--a much easier task than going up--and were the last "tourists" to leave Yamadera. As we walked out the gate, a monk rapped hard on a deep-toned temple bell, signalling the shrine had closed for the day. A GENUINE JAPANESE RESTAURANT After leaving the temples of Yamadera, we returned to Yamagata and Mr. Suzuki and the driver went home. Yoshie had asked us what Japanese restaurants in the U.S. were like, and we could only remark that ones we had visited were steak houses in which a dozen diners sit around a cooking surface while the "chef" makes a theatrical show of preparing and serving their food. Lest we think this was the norm in Japan, she offered to take us to a "real" Japanese restaurant for supper, and we're glad she did. There we had a ten-course meal, most courses consisting of a plate with small portions of several kinds of Japanese delicacies: Roasted Chinese Chestnuts, eggplant, broiled tuna, Yamagata beef, fermented egg yolk (disguised to look like a persimmon), mushrooms, and the like--along with misu soup, hot tea, and a heavenly dessert plate with white coffee pudding and chrysanthemum sherbet. This was a far cry from what we had said many Americans think of as a Japanese restaurant. When we had completed this sumptuous meal we went to pick up Joe at the train station in Yamagata City, where he had just arrived via the bullet train from meetings in Tokyo. COMING HOME; ALMOST NOT Our last day in Japan was Friday, 1 December, but because of a need to depart early for the long drive to the airport we had time only for breakfast; no stroll around Yamagata on this day. Joe Yamaguchi came to the hotel at 8 a.m. along with Mr. Suzuki and the driver, and we all headed off toward Narita. (Yoshie had to teach.)

We had a nearly non-stop conversation with Joe for the next five hours, he eager to hear about life in the United States, and we wanting to understand more about how things work in Japan. Shortly after we left Yamagata, however, we wondered for a moment whether we'd even get to the airport, for as we climbed out of the valley in which the city lies it began to snow heavily on the first mountain ridge. Joe laughed when we told him even a flake or two of white stuff would cause an immediate panic back home in South Carolina, with folks running out to strip grocery store shelves of bread and milk. Our driver assured us through Joe that it would take a lot more precipitation than this to keep him from his appointed task of getting us to the airport, and was kind enough to stop along the highway so we could get a snow photo (above) as another remembrance of Yamagata Prefecture. As we crested the white-shrouded mountain and started the downhill run toward Narita, the weather broke and temperatures rose gradually. By the time we were halfway to the airport we had a partly sunny, balmy day.

We arrived at the Narita two hours ahead of flight departure time, and knowing our three traveling companions still had five hours by car to get back to Yamagata, we bid farewell at the airport, bought a few souvenirs, navigated customs, and boarded Delta's big Boeing 777 for our trip to Atlanta. The return flight was a little faster--12.5 hours instead of 14--and since most of it was in the dark, we actually slept some. After the plane change in Atlanta, it was an hour or so to Charlotte and the welcoming arms of wife Susan. Needless to say, on the car ride home we had lots to tell her about our trip to Japan and all we had seen and experienced in the realms of natural and cultural history. EPILOGUE: GOCHISOSAMA Now that we're back at Hilton Pond Center and into our daily routine, we think often about our trip to Japan--despite our continuing jet lag. We're ever grateful to Dr. Fujiro Sendo and Yamagata University for inviting us to the awards ceremony; our monetary prize was meaningful, but the chance to visit Japan was priceless. We also thank Mr. Suzuki (our escort) and Mr. Kikuchi (the driver) for guiding us safely and treating us like royalty, and especially thank Joe and Yoshie Yamaguchi for all their questions and answers--in English! During our short time in Japan, the Yamaguchis became real friends; we suspect we'll see them again someday. It's impossible for us to express our full gratitude for this wonderful honor and opportunity afforded us by Yamagata University, but we'll try by saying gochisosama--"thanks for the feast"--and thereby thanking everyone who played a role in our life-changing visit to Yamagata Prefecture.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

Comments or questions about this week's installment?

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond." (See Support if you'd like to make a gift of your own.)

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written & photographed You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use our on-line Hilton Pond Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to |

or General (involving "regional culture, cultural activities, or cooperation between universities and society, science, and technology"). In a typically polite gesture, the University added: "Of course, we also welcome original ideas in areas other than those listed above." Yamagata University requested projects that would take no more than 10 million Japanese yen to implement.

or General (involving "regional culture, cultural activities, or cooperation between universities and society, science, and technology"). In a typically polite gesture, the University added: "Of course, we also welcome original ideas in areas other than those listed above." Yamagata University requested projects that would take no more than 10 million Japanese yen to implement. and offered to instruct them on how to write about what they had seen and photographed--all with the goal of making them better science students with greater environmental awareness. We further proposed to have them publish their work to the Web as "An Eye on Nature in Yamagata" (left)--sort of a Japanese version of "This Week at Hilton Pond." Inherent in the plan was cooperation from Yamagata University, which would provide in-house support for student efforts and supply an interpreter when needed so we all could communicate freely. The proposal was pretty straightforward, and we hoped it had enough merit to attract the attention of competition judges. Our suggested budget was modest, about 500,000 yen (including matching in-kind support from Hilton Pond Center).

and offered to instruct them on how to write about what they had seen and photographed--all with the goal of making them better science students with greater environmental awareness. We further proposed to have them publish their work to the Web as "An Eye on Nature in Yamagata" (left)--sort of a Japanese version of "This Week at Hilton Pond." Inherent in the plan was cooperation from Yamagata University, which would provide in-house support for student efforts and supply an interpreter when needed so we all could communicate freely. The proposal was pretty straightforward, and we hoped it had enough merit to attract the attention of competition judges. Our suggested budget was modest, about 500,000 yen (including matching in-kind support from Hilton Pond Center). There we boarded Delta's big Boeing 777 (right)--the first jetliner to be 100% digitally designed using three-dimensional computer graphics instead of full-sized mock-ups--along with nearly 300 other passengers and crew.

There we boarded Delta's big Boeing 777 (right)--the first jetliner to be 100% digitally designed using three-dimensional computer graphics instead of full-sized mock-ups--along with nearly 300 other passengers and crew.  By the time we reached Edmonton, a blanket of white made it quite apparent winter had hit western Canada, and shortly thereafter we crossed over the most breathtaking and inspirational views of the outbound flight: The rugged, snow-covered peaks of the Canadian Rockies (left). It was our first-ever look at this spectacular terrain, and we kept our nose plastered against the cabin window for a very long time. (Who could sleep at a time like this?) Eventually the plane turned a bit, following the Coastal Mountains of Alaska between Juneau and Whitehorse, over Anchorage, and then out to the Bering Sea. We saw nothing but clouds and ocean and in-flight movies for the next eight hours or so until--not far from our destination--we crossed the International Date Line, passed through Russian air space, and then approached Iwaki and the Japanese islands before touching down at Narita Airport at 12:42 a.m. Eastern time (that's 2:42 p.m. Japan time). It was officially a 13-hour, 48-minute trip and we were 6,843 miles away from Atlanta. It's interesting that our route took us over Alaska rather than going due west toward Japan; the latter would have been considerably further. (This may seem hard to believe, but check it out next time you have access to a globe of the world.)

By the time we reached Edmonton, a blanket of white made it quite apparent winter had hit western Canada, and shortly thereafter we crossed over the most breathtaking and inspirational views of the outbound flight: The rugged, snow-covered peaks of the Canadian Rockies (left). It was our first-ever look at this spectacular terrain, and we kept our nose plastered against the cabin window for a very long time. (Who could sleep at a time like this?) Eventually the plane turned a bit, following the Coastal Mountains of Alaska between Juneau and Whitehorse, over Anchorage, and then out to the Bering Sea. We saw nothing but clouds and ocean and in-flight movies for the next eight hours or so until--not far from our destination--we crossed the International Date Line, passed through Russian air space, and then approached Iwaki and the Japanese islands before touching down at Narita Airport at 12:42 a.m. Eastern time (that's 2:42 p.m. Japan time). It was officially a 13-hour, 48-minute trip and we were 6,843 miles away from Atlanta. It's interesting that our route took us over Alaska rather than going due west toward Japan; the latter would have been considerably further. (This may seem hard to believe, but check it out next time you have access to a globe of the world.) Holding the sign was Dr. Joe Yamaguchi (our E-mail correspondent and a linguistics professor at Yamagata University) and Joe's wife Yoshie (yo-shee-ah)--who was to be our official interpreter for the duration of the trip. (At right, Joe and Yoshie examine a book we gave them as a thank-you gift.) They were flanked by Naokatsu Suzuki (senior representative from the office of the University president of Yamagata, on the right in the photo below left) and Noboru Kikuchi (the president's official driver, with necktie, below). We were greatly relieved to hear that Professor Joe spoke perfectly good English, having studied for several years in the U.S. where he specialized in American geographical dialects. He and Yoshie--who herself teaches English to Japanese students at Yamagata University--quickly discerned we lacked the Southern drawl they expected with Hilton Pond Center being in South Carolina,

Holding the sign was Dr. Joe Yamaguchi (our E-mail correspondent and a linguistics professor at Yamagata University) and Joe's wife Yoshie (yo-shee-ah)--who was to be our official interpreter for the duration of the trip. (At right, Joe and Yoshie examine a book we gave them as a thank-you gift.) They were flanked by Naokatsu Suzuki (senior representative from the office of the University president of Yamagata, on the right in the photo below left) and Noboru Kikuchi (the president's official driver, with necktie, below). We were greatly relieved to hear that Professor Joe spoke perfectly good English, having studied for several years in the U.S. where he specialized in American geographical dialects. He and Yoshie--who herself teaches English to Japanese students at Yamagata University--quickly discerned we lacked the Southern drawl they expected with Hilton Pond Center being in South Carolina,  but both understood when they found out our birthplace was Pittsburgh.

but both understood when they found out our birthplace was Pittsburgh. (We suspect those mothers would be more accepting of slurping if they ever tried to eat noodles with chopsticks as in the photo at right.)

(We suspect those mothers would be more accepting of slurping if they ever tried to eat noodles with chopsticks as in the photo at right.) Every item on the plates was perfectly arranged--as noted by the Food Channel in the U.S., "presentation" is indeed a big deal in Japan--so the breakfast was as pleasing to the eye as the palate. We were careful NOT to leave a tip--Yoshie Yamaguchi had told us there was no tipping in Japan--but we did bow appreciatively to our server when we left the dining room.

Every item on the plates was perfectly arranged--as noted by the Food Channel in the U.S., "presentation" is indeed a big deal in Japan--so the breakfast was as pleasing to the eye as the palate. We were careful NOT to leave a tip--Yoshie Yamaguchi had told us there was no tipping in Japan--but we did bow appreciatively to our server when we left the dining room.

When the roofs WERE straight, they were accented by ornaments--special ornate tiles or gargoyle-like structures that broke up the sight line. For us, these Oriental roofs were inspirational, drawing our eyes upward toward the Yamagata sky--and certainly not what you'd find on a building put up in a hurry by unskilled workers instead of artisan-craftsmen.

When the roofs WERE straight, they were accented by ornaments--special ornate tiles or gargoyle-like structures that broke up the sight line. For us, these Oriental roofs were inspirational, drawing our eyes upward toward the Yamagata sky--and certainly not what you'd find on a building put up in a hurry by unskilled workers instead of artisan-craftsmen.

We suddenly recalled that Yamagata is famous for deep winter snowfalls, so now the ropes made perfect sense. They were tied to limbs to keep them from being broken by heavy, wet snow. It's hard to imagine how much time it takes to tie all these trees each fall, but considering how our two big ornamental Camellias look some winters after an ice storm, we'll consider implementing the rope trick at Hilton Pond Center. By the way, it would be impossible for Yamagata gardeners to protect their multi-trunked shrubs in similar fashion with poles and ropes; instead, they build little bamboo lean-to structures (above left) that let in light and moisture but keep heavy snows from crushing vegetation.

We suddenly recalled that Yamagata is famous for deep winter snowfalls, so now the ropes made perfect sense. They were tied to limbs to keep them from being broken by heavy, wet snow. It's hard to imagine how much time it takes to tie all these trees each fall, but considering how our two big ornamental Camellias look some winters after an ice storm, we'll consider implementing the rope trick at Hilton Pond Center. By the way, it would be impossible for Yamagata gardeners to protect their multi-trunked shrubs in similar fashion with poles and ropes; instead, they build little bamboo lean-to structures (above left) that let in light and moisture but keep heavy snows from crushing vegetation.

The Big-billed Crow well-documented as a city bird--it is quite common in Tokyo where its numbers are increasing dramatically. Since the streets of Yamagata were meticulously clean, we're not sure how crows there find enough to eat before the annual persimmon crop comes in.

The Big-billed Crow well-documented as a city bird--it is quite common in Tokyo where its numbers are increasing dramatically. Since the streets of Yamagata were meticulously clean, we're not sure how crows there find enough to eat before the annual persimmon crop comes in. the Japanese eventually developed an alphabet that enables them to spell out words letter by letter as we do in English.) As a result of our expressed interest in Samurai culture, Yoshie and Mr. Suzuki decided it would be nice for us to visit the nearby city of Kaminoyama and its restored castle, first built in 1535 by the Mogami clan. According to a castle brochure, the structure was home of the local governor, or Daimyo, "second in power only to the Shogun who was the real ruler of Japan, the Emperor being only a figurehead. The economy of the people and indeed their very livelihood was under complete control of the Daimyo." During ensuing struggles, the original castle was claimed by the Toki clan, but the Tokis were reassigned to another part of Japan and the old structure was torn down in 1692.

the Japanese eventually developed an alphabet that enables them to spell out words letter by letter as we do in English.) As a result of our expressed interest in Samurai culture, Yoshie and Mr. Suzuki decided it would be nice for us to visit the nearby city of Kaminoyama and its restored castle, first built in 1535 by the Mogami clan. According to a castle brochure, the structure was home of the local governor, or Daimyo, "second in power only to the Shogun who was the real ruler of Japan, the Emperor being only a figurehead. The economy of the people and indeed their very livelihood was under complete control of the Daimyo." During ensuing struggles, the original castle was claimed by the Toki clan, but the Tokis were reassigned to another part of Japan and the old structure was torn down in 1692.

including a magnificent Samurai suit of armor that proves at least some of these Japanese warriors were quite small in stature. The Samurai saga is too long and convoluted to explain herein, but it's so fascinating we encourage you to read about it elsewhere.(Photos were not permitted within Kaminoyama Castle, so we've included at right a photo of representative Samurai armor, made of bamboo, metal, leather, and colorful cloth. The antler-like adornment on the helmet was indicative of the warrior's clan. A lacquered wooden mask not only protected the face but also made the Samurai look all the more fierce.)

including a magnificent Samurai suit of armor that proves at least some of these Japanese warriors were quite small in stature. The Samurai saga is too long and convoluted to explain herein, but it's so fascinating we encourage you to read about it elsewhere.(Photos were not permitted within Kaminoyama Castle, so we've included at right a photo of representative Samurai armor, made of bamboo, metal, leather, and colorful cloth. The antler-like adornment on the helmet was indicative of the warrior's clan. A lacquered wooden mask not only protected the face but also made the Samurai look all the more fierce.)

As we finished the meal and prepared to get up from the dining table, Yoshie quietly clapped her hands together in prayerful style, bowed slightly toward Mr. Suzuki, and said "Gochisosama," and he replied in kind. Knowing the University, through Mr. Suzuki, was paying for this meal and everything else about our trip, we asked Yoshie if she was thanking our host for picking up the check. Her response was fascinating and thought-provoking. In part, Yoshie said, she was indeed thanking Mr. Suzuki for the meal, but that gochisosama has a much deeper meaning. (After we got home from Japan, we looked up the word on the Internet and found its literal translation is "thanks for the feast," but we much prefer Yoshie's philosophical explanation, as follows.)

As we finished the meal and prepared to get up from the dining table, Yoshie quietly clapped her hands together in prayerful style, bowed slightly toward Mr. Suzuki, and said "Gochisosama," and he replied in kind. Knowing the University, through Mr. Suzuki, was paying for this meal and everything else about our trip, we asked Yoshie if she was thanking our host for picking up the check. Her response was fascinating and thought-provoking. In part, Yoshie said, she was indeed thanking Mr. Suzuki for the meal, but that gochisosama has a much deeper meaning. (After we got home from Japan, we looked up the word on the Internet and found its literal translation is "thanks for the feast," but we much prefer Yoshie's philosophical explanation, as follows.) And, as always, we're acknowledging the sacrifice made by the shrimp and the eggplant and the rest of nature so we could enjoy this meal and find sustenance in it."

And, as always, we're acknowledging the sacrifice made by the shrimp and the eggplant and the rest of nature so we could enjoy this meal and find sustenance in it." Mr. Suzuki ushered us into the president's office--a spacious, well-lit room with low couches and tables. Dr. Sendo is also a medical doctor who speaks English, having had an appointment at the National Institutes of Health in Washington for a year or so. He welcomed us warmly and asked us to tell him about our academic career and Hilton Pond Center. Before departing we offered him a small gift--a brass Bachman's Warbler ornament we designed for the

Mr. Suzuki ushered us into the president's office--a spacious, well-lit room with low couches and tables. Dr. Sendo is also a medical doctor who speaks English, having had an appointment at the National Institutes of Health in Washington for a year or so. He welcomed us warmly and asked us to tell him about our academic career and Hilton Pond Center. Before departing we offered him a small gift--a brass Bachman's Warbler ornament we designed for the  The six winners were seated at a long table facing the front lectern, and behind us were additional rows of tables with members of the press and University vice presidents, department chairs, and members of the board of trustees.

The six winners were seated at a long table facing the front lectern, and behind us were additional rows of tables with members of the press and University vice presidents, department chairs, and members of the board of trustees.

Such monuments--some hundreds of years old--are scattered throughout the prefecture. Dr. Dobashi's grant money will be used to find as many as possible, locate them precisely with GPS devices, photograph them, and create a permanent catalog so the somokoto and their sentiments can be preserved. The somokoto are another great indicators of how reverent many Japanese are toward nature and the environment; we can't recall any instances of an American developer erecting a marker to remind folks natural habits and organisms were lost to allow for construction of a new shopping mall or subdivision. It takes a very different mindset to think about nature in this way, and we're hopeful Dr. Dobashi's project will continue to remind younger Japanese about natural history even as they are pressured to become more Americanized.

Such monuments--some hundreds of years old--are scattered throughout the prefecture. Dr. Dobashi's grant money will be used to find as many as possible, locate them precisely with GPS devices, photograph them, and create a permanent catalog so the somokoto and their sentiments can be preserved. The somokoto are another great indicators of how reverent many Japanese are toward nature and the environment; we can't recall any instances of an American developer erecting a marker to remind folks natural habits and organisms were lost to allow for construction of a new shopping mall or subdivision. It takes a very different mindset to think about nature in this way, and we're hopeful Dr. Dobashi's project will continue to remind younger Japanese about natural history even as they are pressured to become more Americanized. and we welcomed the opportunity to tell everyone--through Yoshie (right)--how honored WE were to be able to attend. Following our remarks Dr. Sendo opened the floor to questions from the press, after which everyone was directed to another room in the hotel for a reception. As we prepared to leave the ballroom, we were wondering what to do with our impressively large certificate when, almost by magic, a University staffer appeared with a very nice faux alligator mailing tube into which he rolled the parchment. And then, as we walked out the door, another staffer handed us a custom-made wooden picture frame into which we could place the certificate after we arrived home. President Sendo and his crew had thought of everything!

and we welcomed the opportunity to tell everyone--through Yoshie (right)--how honored WE were to be able to attend. Following our remarks Dr. Sendo opened the floor to questions from the press, after which everyone was directed to another room in the hotel for a reception. As we prepared to leave the ballroom, we were wondering what to do with our impressively large certificate when, almost by magic, a University staffer appeared with a very nice faux alligator mailing tube into which he rolled the parchment. And then, as we walked out the door, another staffer handed us a custom-made wooden picture frame into which we could place the certificate after we arrived home. President Sendo and his crew had thought of everything!

How could anyone think of such a splendid plant as Tall Goldenrod as an invasive? Well, it's just another example of the wrong plant being in the wrong place at the wrong time. S. canadensis simply doesn't belong in Japan, where it somehow is able to outcompete native flora enough to become a real problem--just as many plants from Europe, Asia, and Africa do in the United States. In the words of horticulture students at Japan's Tsuchiura First High School (whose Web site provided the photo above left of Tall Goldenrod in its non-native land): "We see lots of Tall Goldenrod on the riverside or in wastelands that are not cared for. Tall Goldenrod at riverside restrains native species. It means Tall Goldenrod can grow even in a place where the environment is comparatively bad, so these plants are able to successfully survive in Japan as well as in their original land." Ouch!

How could anyone think of such a splendid plant as Tall Goldenrod as an invasive? Well, it's just another example of the wrong plant being in the wrong place at the wrong time. S. canadensis simply doesn't belong in Japan, where it somehow is able to outcompete native flora enough to become a real problem--just as many plants from Europe, Asia, and Africa do in the United States. In the words of horticulture students at Japan's Tsuchiura First High School (whose Web site provided the photo above left of Tall Goldenrod in its non-native land): "We see lots of Tall Goldenrod on the riverside or in wastelands that are not cared for. Tall Goldenrod at riverside restrains native species. It means Tall Goldenrod can grow even in a place where the environment is comparatively bad, so these plants are able to successfully survive in Japan as well as in their original land." Ouch! From these meetings we went off on a walking tour of Yamagata University's two main campuses that include medical and nursing schools and a teaching hospital. Also in the complex are schools of literature, social science, education, art, and science.

From these meetings we went off on a walking tour of Yamagata University's two main campuses that include medical and nursing schools and a teaching hospital. Also in the complex are schools of literature, social science, education, art, and science.

A serpentine trail wandered throughout the garden but always afforded a view of the central pond--laid out in the shape of the Chinese character for "heart" and complete with a complement of carp in many colors (right). Gardeners had already implemented the pole-and-rope system of protecting trees, and almost every low shrub had a bamboo lean-to for warding off soon-to-come snows.

A serpentine trail wandered throughout the garden but always afforded a view of the central pond--laid out in the shape of the Chinese character for "heart" and complete with a complement of carp in many colors (right). Gardeners had already implemented the pole-and-rope system of protecting trees, and almost every low shrub had a bamboo lean-to for warding off soon-to-come snows.

As is the custom in private homes, tea houses, shrines, and some other buildings in Japan, we removed our shoes and followed our guide into the tea house in our stocking feet. Although shoe removal is traditional and a sign of respect, we think there's also a touch of practicality in the practice; the floors of the tea house were covered with tatami and goza--finely woven reed mats that street shoes would have shredded pretty quickly. (See photo of a typical tea house, above left.) The tea ceremony itself was highly ritualized; the young woman who prepared the tea folded the napkins, wiped the utensils, and poured the tea had studied long to learn how to do it just so. Even the guests had to partake of the sweet snack and tea in certain ways; we were asked, for example, to remove our rings so they would not cause distraction by clinking against the tea cup, and we had to turn and hold the cup according to tradition.

As is the custom in private homes, tea houses, shrines, and some other buildings in Japan, we removed our shoes and followed our guide into the tea house in our stocking feet. Although shoe removal is traditional and a sign of respect, we think there's also a touch of practicality in the practice; the floors of the tea house were covered with tatami and goza--finely woven reed mats that street shoes would have shredded pretty quickly. (See photo of a typical tea house, above left.) The tea ceremony itself was highly ritualized; the young woman who prepared the tea folded the napkins, wiped the utensils, and poured the tea had studied long to learn how to do it just so. Even the guests had to partake of the sweet snack and tea in certain ways; we were asked, for example, to remove our rings so they would not cause distraction by clinking against the tea cup, and we had to turn and hold the cup according to tradition. The sushi bar was a very long counter with perhaps two dozen stools facing a small, continuously moving conveyor belt (right), reminiscent of the baggage claim area at an airport. As long as patrons were in the restaurant, the conveyer ran past sushi chefs who were constantly preparing sushi dishes and placing sending them along on the belt. As a tempting looking plate arrived, the patron snatched it from the conveyor and chowed down appreciatively, waiting for the next variety of tuna, whitefish, or salmon eggs to come by. It was also possible to make special orders, which is what we did when Yoshie suggested we simply start at the top of the sushi menu and try each of the dishes in numerical order. This we did, until--after item number 10--we decided we had probably had enough. Apologizing to Yoshie for gluttony, we were surprised she encouraged us to keep going, so we had six or so more before we really called it quits. In short, the sushi dishes were all superb except for the fermented soybeans (Joe Yamaguchi said it's an acquired taste that even many Japanese don't like) and the sea urchin (whose taste reminded us of the odor of a saltwater aquarium that failed long ago in our high school biology lab).

The sushi bar was a very long counter with perhaps two dozen stools facing a small, continuously moving conveyor belt (right), reminiscent of the baggage claim area at an airport. As long as patrons were in the restaurant, the conveyer ran past sushi chefs who were constantly preparing sushi dishes and placing sending them along on the belt. As a tempting looking plate arrived, the patron snatched it from the conveyor and chowed down appreciatively, waiting for the next variety of tuna, whitefish, or salmon eggs to come by. It was also possible to make special orders, which is what we did when Yoshie suggested we simply start at the top of the sushi menu and try each of the dishes in numerical order. This we did, until--after item number 10--we decided we had probably had enough. Apologizing to Yoshie for gluttony, we were surprised she encouraged us to keep going, so we had six or so more before we really called it quits. In short, the sushi dishes were all superb except for the fermented soybeans (Joe Yamaguchi said it's an acquired taste that even many Japanese don't like) and the sea urchin (whose taste reminded us of the odor of a saltwater aquarium that failed long ago in our high school biology lab).

What remarkable dedication to faith was shown by these Buddhist holy men, who kept the fire burning through war and peace, feast and famine, good times and bad. In the United States we rightfully pride ourselves on protecting historical spots such as those from the Revolutionary War some 235 years ago. As important as our American sites are to us, their longevity pales beside this temple and its flame that has burned for more than a millennium.

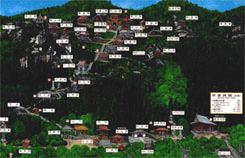

What remarkable dedication to faith was shown by these Buddhist holy men, who kept the fire burning through war and peace, feast and famine, good times and bad. In the United States we rightfully pride ourselves on protecting historical spots such as those from the Revolutionary War some 235 years ago. As important as our American sites are to us, their longevity pales beside this temple and its flame that has burned for more than a millennium. Next a big map board showed all the smaller Buddhist shrines and monks' quarters that make up the rest of the Yamadera complex (above left; click

Next a big map board showed all the smaller Buddhist shrines and monks' quarters that make up the rest of the Yamadera complex (above left; click

Each of the small Buddhist shrines--tended by an individual monk and perhaps a trainee--was an example of traditional Japanese architecture, and served as testimony to the heartfelt dedication of these men. Their religious traditions go back thousands of years, but they seem to embrace the 21st century--as evidenced by the satellite dish (!) atop one of the monks' houses near the summit of Yamadera.

Each of the small Buddhist shrines--tended by an individual monk and perhaps a trainee--was an example of traditional Japanese architecture, and served as testimony to the heartfelt dedication of these men. Their religious traditions go back thousands of years, but they seem to embrace the 21st century--as evidenced by the satellite dish (!) atop one of the monks' houses near the summit of Yamadera. Despite Joe's long day of work and three-hour train ride, he and Yoshie went back to the hotel for a final evening of conversation and farewells. As a small token of our appreciation for everything they had done to make our trip to Japan possible and pleasurable, we gave each of our new friends one of our world-famous Operation Ruby-throat T-shirts. We also had brought along a copy of P is for Palmetto, a splendid little picture book that includes a page for each letter of the alphabet linked with something about South Carolina beginning with that letter. Since Joe is a linguistic professor and Yoshie teaches English to Japanese students, they were delighted with the book; we suspect they'll even end up using it with their students. After an obligatory farewell photo (above right), the Yamaguchis went home, and we went up to bed.

Despite Joe's long day of work and three-hour train ride, he and Yoshie went back to the hotel for a final evening of conversation and farewells. As a small token of our appreciation for everything they had done to make our trip to Japan possible and pleasurable, we gave each of our new friends one of our world-famous Operation Ruby-throat T-shirts. We also had brought along a copy of P is for Palmetto, a splendid little picture book that includes a page for each letter of the alphabet linked with something about South Carolina beginning with that letter. Since Joe is a linguistic professor and Yoshie teaches English to Japanese students, they were delighted with the book; we suspect they'll even end up using it with their students. After an obligatory farewell photo (above right), the Yamaguchis went home, and we went up to bed.

Unlike our auto trip on the previous Tuesday, it was daylight for the ride to the airport on departure day. That provided a chance to observe roadside vegetation along the way. Sure enough, we spotted several infestations of Kudzu (kuzu)--which in Japan means one spindly vine growing a few feet up a pine tree, NOT the massive landscape-blanketing problem we have in the Carolina Piedmont. And, sure enough, at various places we spotted dense clumps of an even more-familiar plant--the seed heads of Tall Goldenrod (left) that traveled somehow from America and became an invasive plant in Japan.

Unlike our auto trip on the previous Tuesday, it was daylight for the ride to the airport on departure day. That provided a chance to observe roadside vegetation along the way. Sure enough, we spotted several infestations of Kudzu (kuzu)--which in Japan means one spindly vine growing a few feet up a pine tree, NOT the massive landscape-blanketing problem we have in the Carolina Piedmont. And, sure enough, at various places we spotted dense clumps of an even more-familiar plant--the seed heads of Tall Goldenrod (left) that traveled somehow from America and became an invasive plant in Japan.

Oct 15 to Mar 15

Oct 15 to Mar 15