|

|

|||

|

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

Tired of all that ice and snow? This week holds your last chance for you to escape on our |

|

HUMMINGBIRD SKULL & SKELETON

After last week's photo essay about bird skulls, we got E-mails at Hilton Pond Center from folks wondering why--considering all our work with Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--we didn't include a hummer skull in our discussion. The honest answer was our collection did not contain a hummingbird skull, per se. However, we DID have the mummified remains of a hatch-year male ruby-throat someone brought to us last summer after the hummer crashed into a window. Since the bird wasn't usable as a study skin--some feathers were missing and insect larvae had already degraded the specimen--we decided to see if we could salvage a hummingbird skull for this week's installment.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The hummer was decapitated, so we took the head--mostly covered by skin and feathers (as in the adult male above)--and began removing plumage with forceps and fingertips. After we had plucked as much as would loosen without bone-breaking force--not a whole lot when dealing with a hummingbird skull--we soaked the head overnight in a dish of water and went to work again. By now the skin was soft enough that we could tease it from the bone, revealing a few strips of muscle that also peeled off easily. The sclerotic ring--"eye bones"--came away with the skin. Our only difficulty--other than needing a strong hand lens to see what we were doing--was in trying to preserve the delicate roots of the tongue. (We were only partly successful.) In the end we had a usable, albeit not perfectly clean hummingbird skull we could compare with those from other birds.

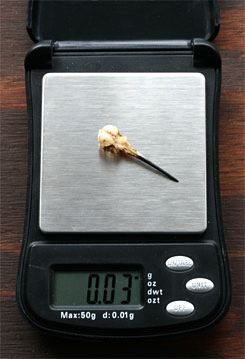

The first phenomenal thing about a hummer's skull, of course, is its diminutive size (above, magnified about four times). From the tip of the bill to the rear of the cranium, our young male's skull measured a tad more than 1.25 inches, with about 70% of that being mandibles. (Because a female ruby-throat is somewhat bigger than the male, we'd expect her to have an similarly larger skull.) The hummer's skull was light-weight and filled with air spaces--it actually floated in the saucer of water when we soaked it to loosen the skin-- We couldn't pass up the opportunity to put the dried skull on a portable Escali digital electronic balance we use to weigh live hummingbirds when banding. The skull (with bill sheath) weighed an ultralight 0.03 grams--about 1% of the weight of a living hatch-year male ruby-throat that would tip the scales at about 3.0 grams or so. After doing a little Web searching, we were surprised to learn the skull of an adult human male weighs about two pounds--also about 1% of his overall weight. We anticipated the skull weight to body weight ratio in a aerobatic hummingbird would be much less than that of a terrestrial human, but it appears the long, pointed mandibles in the hummer are relatively heavy. Besides, human skulls are made lighter by extensive sinus cavities and optimal thinning of bone in just the right places. Although humans don't fly, it's good we are somewhat "light-headed," lest a weighty cranium place even more strain on our neck muscles and vertebra and make it hard to hold high our heads.

Another amazing aspect of a hummingbird's internal anatomy appeared when we looked at the underside of its skull (above). Although in humans the tongue is relatively short and rooted in the hyoid bone at the top of the trachea, a hummingbird's exceedingly long tongue forks at the apex of the mandibles with each fork continuing along the base of the skull, past the foramen magnum (spinal nerve opening), and up the rear of the skull and across its top, finally terminating between the eyes. The hummer's tongue itself isn't just muscle but includes a series of small bones folded accordion-like. When a Ruby-throated Hummingbird flexes its tongue muscles, these bones unfold and allow the hummer to extend its tongue almost an inch past the tip of the nearly inch-long bill. Only hummingbirds and woodpeckers have such a lengthy hyoid apparatus and tongue.

Above is our lateral photo of a Ruby-throated Hummingbird skeleton prepared by Stanlee Miller of Clemson University. It reveals another characteristic of all hummingbirds: An enormous sternum (keel, or breastbone) to which large pectoral (breast) muscles are attached; a hummingbird keel is much longer than in most birds. The photo shows the hummer's wing bones, including a very short humerus and fused bones of the hand that are also seen from a frontal perspective (below right). The front view provides a different look at the faintly visible hyoid bones of the tongue and their insertion in the bird's inter-ocular region. Other Facts: The skeleton of a Ruby-throated Hummingbird includes a few solid bones, but most are porous or--in the case of the wing and leg bones--hollow. Typically hummingbirds have eight pairs of ribs, while most other birds have only six pairs. The ruby-throat's wing attaches to the sternum in a tiny ball-and-socket joint unique to hummingbirds and swifts; this allows flexibility of wing movement required for hovering and backwards flight. Hummingbirds have extremely short exposed legs (tarsometatarsi) but relatively long toes (three in front and one--the "hallux"--in back); because of their leg and foot structure hummers perch perfectly well but are incapable of walking on the ground. There are 14 or 15 neck vertebrae in a hummingbird--compared to just seven in most mammals. People often ask us how many total bones a hummingbird has in its skeleton, but there is no definitive answer. For instance, the bony ring that surrounds each eye (below left) is made up of 12 or more small parts (ossicles);

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center NOTE: Federal and state laws require permits for possession of ALL migratory birds (dead or alive) and ALL artifacts from them, including nests, eggs, feathers, and skeletal materials. In general, these permits are limited to education and research institutions. If you need a hummingbird skull but don't have the necessary permits, you can order a nice replica from Bone Clones Inc.

Comments or questions about this week's installment?

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond."

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written & photographed You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use our on-line Hilton Pond Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to |

and its bones were so thin in many places they were translucent and nearly transparent.

and its bones were so thin in many places they were translucent and nearly transparent.

Note that in this particular skeleton (above) the tongue--which naturally splits at the tip--protrudes slightly; in a live bird the tongue is completely hidden within the bill until extended three or four times a second to lap up nectar or sugar water. (No, hummingbirds do NOT suck.)

Note that in this particular skeleton (above) the tongue--which naturally splits at the tip--protrudes slightly; in a live bird the tongue is completely hidden within the bill until extended three or four times a second to lap up nectar or sugar water. (No, hummingbirds do NOT suck.) there's no agreement whether each of these counts as an individual "bone" or if the entire ensemble of ossicles (the sclerotic ring) should be considered a single bone. In addition, the cranium, mandibles, and pelvic girdle are each comprised of many bones that in adult hummers are more or less fused, and then there are those several small bones in the hummingbird's tongue apparatus. To further complicate matters, different hummingbird species have different numbers of ribs and toe joints, so we're not dodging the question when we say we can't tell you how many bones make up the skeleton of a hummer. All we know is this tiny bird's skeleton is amazing to look at and that--at true life-size (below)--the new Ruby-throated Hummingbird skull in our collection at Hilton Pond Center is a heckuva lot smaller than one from a Barred Owl.

there's no agreement whether each of these counts as an individual "bone" or if the entire ensemble of ossicles (the sclerotic ring) should be considered a single bone. In addition, the cranium, mandibles, and pelvic girdle are each comprised of many bones that in adult hummers are more or less fused, and then there are those several small bones in the hummingbird's tongue apparatus. To further complicate matters, different hummingbird species have different numbers of ribs and toe joints, so we're not dodging the question when we say we can't tell you how many bones make up the skeleton of a hummer. All we know is this tiny bird's skeleton is amazing to look at and that--at true life-size (below)--the new Ruby-throated Hummingbird skull in our collection at Hilton Pond Center is a heckuva lot smaller than one from a Barred Owl.

Oct 15 to Mar 15

Oct 15 to Mar 15