|

|

|||

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

LIKE NATURE?

DON'T CUT YOUR GRASS As we often mention, back in 1982 the 11 acres that now comprise Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History were almost completely open, having been in row crops (corn, cotton, and soybeans) or grazed by cattle and other livestock for perhaps a hundred years. When we moved to the property, we made a pact with the land: We promised to quit mowing the grass if the land would exercise its age-old right to natural succession and cover the acreage with wildflowers, shrubs, vines, and trees. We've been mostly true to our promise--about the only thing we cut regularly is our meandering nature trails and small patches of lawn around the old farmhouse--and the land has responded in-kind. Now, after 26 years of what we call "laissez-faire land management," the property is covered in large part by a young hardwood forest--a pretty fair exchange for giving up lawn-mowing. This spring--due mostly to illness and travel away from Hilton Pond Center--we even dispensed with trimming the front yard, and we've been amazed at how quickly, extensively, and attractively nature reclaimed that little patch of grass. This week, our photo essay reveals just how natural your own yard might become next spring if you simply stop cutting your grass.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center By mid-May, the most vigorous and noticeable natural growth was a large patch of four-foot-tall Daisy Fleabane, Erigeron annuus, that erupted in the front yard at the edge of the driveway to Hilton Pond Center (above). This showy plant, whose name comes from its flower's resemblance to the Ox-eye Daisy and reputed ability to repel fleas, grows in open meadows and roadsides across much of the country--even during drought conditions that have laid low many ornamentals in recent weeks. The composite flower head (below) consists of sterile white ray flowers and fertile, seed-producing yellow disk flowers; the entire structure is only about a half-inch across--considerably smaller than the two-inch blossom of a wild daisy.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We were surprised our Daisy Fleabanes created a near-monoculture in one corner of the yard. Although a few grew elsewhere, most sprouted in a dense cluster of perhaps a hundred separate stems. We're not sure where all the fleabane seeds came from to produce this patch, but since the plant is an annual they may have arrived on gusty winds last year and spent the winter beneath leaf litter. We also noticed that despite our thousands of front yard fleabane blossoms, very few pollinators were visiting. Aside from an occasional solitary bee, the only other insect we saw was a nearly invisible 1/32" immature true bug probing for nectar (above, species unknown). It may be that at least some fleabane disk flowers get self-pollinated.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center After searching the fleabane stand for insects, we directed our attention to ground level in a moist area closer to the front porch of our old farmhouse. There, in leafy mulch beneath a tall, established Camellia shrub, we found a familiar plant with three serrated leaves that fortunately was NOT Poison Ivy. Instead it was Indian Strawberry, Duchesnea indica, so-called because it is generally thought to have been imported to this country from the Indian Subcontinent--although some botanists claim it's actually a native North American species. Here at Hilton Pond Center the Indian Strawberry bears in April a yellow bloom that gives rise to a deep red fruit resembling--but tasting far blander than--any of the true Wild Strawberries, Fragaria spp.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Like its more palate-pleasing relatives, the Indian Strawberry produces a fruit with achenes (above)--seeds that grow on the outside of the pulp rather than within. Achenes facilitate the distribution of the genes of a given strawberry plant, sometimes to entirely new habitats when a bird or mammal eats the berry and deposits its seeds some distance away. Indian Strawberry also propagates over shorter distances via above-ground vines called "stolons"; these radiate from the mother plant and produce a daughter where a stolon touches earth and grows roots.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center When we shined a bright light into the open end of a calyx (below left), we could see dark bodies within, and as we tapped the calyx on our palm many of the dark objects fell out (below right). These are the hard, slightly warty seeds of Lyre-leafed Sage, and since each calyx held two or three or four of them we understood how this plant could be so prolific in our Hilton Pond front yard and other locales across the Carolinas.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another decorative plant liable to show up in your yard sooner or later after you stop cutting grass is sometimes associated with the Irish. Folks misidentify its tripartite leaf as being a clover, but it's well-known to botanists and gardeners alike by its common AND scientific name of Oxalis, in this case the Violet Wood Sorrel, Oxalis violacea (below). There are about 30 native species in North America; our favorite is Common Wood Sorrel, O. montana, found carpeting the forest floor beneath hemlock stands in the Carolina mountains. For the record, the true Irish shamrock isn't an Oxalis; it's White Clover, Trifolium repens.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The leaves and stems of many Wood Sorrel species have a tart but pleasant taste caused by oxalic acid. In fact, the genus name Oxalis comes from the greek word for "sour"; nature-wise youngsters who've nibbled on a small yellow imported form called Sour Grass, O. europea, undersatand this "sour" trait. Wild foods enthusiasts frequently use Oxalis greens in salads or to make a refreshing lemonade-like beverage, while deer and rabbits also browse on its foliage. Wood Sorrel seeds are taken by Bobwhite, Mourning Doves, and various sparrows, including juncos.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Because of rapid growth exhibited by some Wood Sorrels, the aggressive gardener often goes after them--some native, some not--with a vengeancem ripping them from the soil. Personally, we welcome all Wood Sorrels for their color, delicate flower markings, and eye-pleasing leaves. If we may pen a rhyme, "The Wood Sorrel bloom will never appear if you graze your yard with a noisy John Deere."

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center As we ride our bicycle around the back roads of York County during certain times of the year, one way we know homeowners are cutting their lawns is to simply inhale. Newly mown grass has a distinctive smell, of course, but what really hits us in the olfactory lobes as we pedal is the unmistakable odor of just-cut Wild Onions, Allium spp. Sundry kinds of onions grow in the Carolinas, and in spring their underground, edible bulbs produce dark green, almost-cylindrical, edible leaves. The Old Farmer's Almanac suggests several days in March and April--those "when the moon is in the sign of the heart which is Leo"--when one can kill wild onions by simply mowing them, with the caveat the plants will come back in autumn. (Doesn't seem like they'd come back if they'd really been killed.) In reality, one-time mowing will not kill onions because the bulb--also edible--is laden with enough energy to produce many generations of new leaves. Mowing does keep the plants from flowering, however, and thus from producing seed heads like the half-ripe one pictured above. When the seeds are mature, they'll turn a ghostly white.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We grudgingly admit some plants that showed up this spring in the uncut lawn at Hilton Pond Center might be classified as "weeds." What is a weed, one asks? One definition is it is "a plant growing where it's not wanted," but our favorite explanation is that "a weed is merely a plant whose virtues have not yet been discovered." Both definitions probably apply to English Plantain, Plantago lanceolata, shown above. This plant invaded North America so long ago--perhaps arriving in the 1600s with settlers at Jamestown--that it's practically a native. The connection between European settlements and English Plantain was not lost on Native Americans who called the plant "white man's footprints," a nickname alluding not only to plantain's invasive qualities but also to the foot-like shape of its basal leaves. English Plantain is amazingly resilient, growing in spoil places where many plants would simply perish; nonetheless, most lawnsmen ignore it or try to kill it with digging or weed killer. In close-up view above, we find the flower stalk of English Plantain to be pleasing to the eye, so we tend to let it be when it shows up on our property. We also understand its greens are good for constipation.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Take a good look at the leaf in the photo above. Is there any denying its symmetry, intricate venation, and deep green coloration would look good in a garden--or growing the in front yard at Hilton Pond Center? Well, the plant that produced the leaf IS doing quite well locally, but you can imagine what a gasoline-powered mower blade would do to this five-inch-long mature foliage of Common Blue Violet, Viola sororia. Many violets occur naturally in North America and the Carolinas, but numerous varieties imported from Europe and Asia have escaped cultivation and show up as pioneer plants. We have a magnificent stand of our native Common Blue Violets at the Center that flowers in early spring and then puts its energy into making the biggest, showiest green leaves one might want. In our judgment the violet patch is just as attractive as any cultivated Hostas that gardeners spend countless hours planting and tending, but all we do to benefit from our expanse of green is turn off the mower and avoid tromping in the wrong place. Ah, the joys of natural succession.

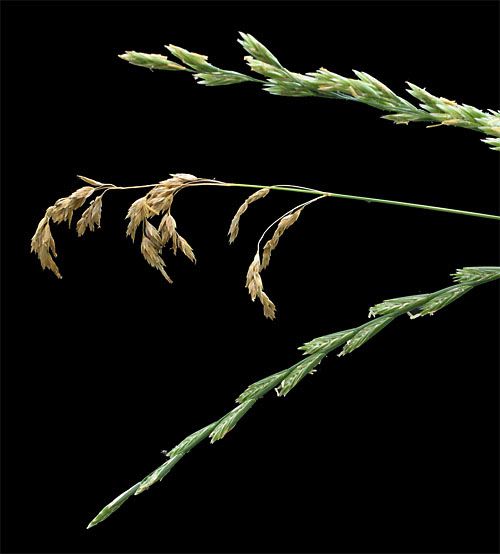

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center When folks mow their grassy yards on a regular schedule, not only do they NOT get to see violets and Indian Strawberries and Daisy Fleabane and the other plants depicted above, they also never get to see flowers and seeds of grasses. If we believe the propaganda of the lawn care companies, grass is something that is deep, dark green and designed to grow two inches tall, more or less, without intrusion by leafy plants. Leave grass to its own devices, however, and it will grow much taller, eventually producing a flowering stalk bearing seeds that, wonder of wonders, can eventually germinate and make new grass plants--WITHOUT the presence of chemical fertilizers. The only disadvantage of grass flowers such as those in the photo above is they make pollen that may cause hay fever, but this relatively minor annoyance is outweighed by grasses' ability to colonize bare soil and provide important cover and food for birds and other wildlife. We're always amazed at how quickly nature "takes back" a piece of land when humans quit disturbing it, whether it's an old farm that reverts to woodland when the plowing stops or a front yard that becomes a natural paradise when one puts away the mower. Within the city limits the well-meaning but misinformed weed ordinance cop may write you a ticket if you "let your property go," but it's probably worth it just to see if your yard responds as magnificently as did ours this spring at Hilton Pond Center when we quit cutting the grass. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center POSTSCRIPT #1: Try as we might, we're not always able to identify every plant that appears on the 11 acres that make up Hilton Pond Center. One such plant with inch-wide purple flowers showed up in the front yard when we quit mowing this year. We're not sure if this five-petalled pioneer is native or a foreign import, but we include a photo below in the hope a Web site visitor can identify it for us. If you know its name(s)--preferably common and scientific--please send a note to us at INFO.

POSTSCRIPT #2: We got nearly 15 e-mails from folks who knew the name of our mystery plant. It's Wild Petunia, Ruellia caroliniensis. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Comments or questions about this week's installment?

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond." (Please see Support if you'd like to make a gift of your own.)

IMPORTANT NOTE: If you ever shop on-line, you may be interested in becoming a member of iGive, through which nearly 700 on-line stores from Barnes and Noble to Lands' End will donate a percentage of your purchase price in support of Hilton Pond Center and Operation RubyThroat. We've just learned that for every new member who signs up and makes an on-line purchase within 45 days iGive will donate an ADDITIONAL $5 to the Center. Please sign up by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless and important way for YOU to support our work in conservation, education, and research. "This Week at Hilton Pond" is written & photographed You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use our on-line Hilton Pond Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to |

As noted, the Indian Strawberry fruit of mid-May is the result of a flower that appeared at least a month earlier--which demonstrates our Hilton Pond front yard has been going through its own version of vegetative succession at a fairly rapid clip. Such is the case with another plant whose roots and basal leaves have been present on the front lawn for at least a year and probably longer: Lyre-leafed Sage, Salvia lyrata. This native square-stemmed mint is a perennial that produces pale purplish-blue blossoms in April (right), but by mid-May all that remains of the flowers is a foot-tall stalk with clusters of fuzzy half-inch brown structures (side view below). Each of these is a cup-like calyx, made of sepals that protected the sage's flower petals as they formed.

As noted, the Indian Strawberry fruit of mid-May is the result of a flower that appeared at least a month earlier--which demonstrates our Hilton Pond front yard has been going through its own version of vegetative succession at a fairly rapid clip. Such is the case with another plant whose roots and basal leaves have been present on the front lawn for at least a year and probably longer: Lyre-leafed Sage, Salvia lyrata. This native square-stemmed mint is a perennial that produces pale purplish-blue blossoms in April (right), but by mid-May all that remains of the flowers is a foot-tall stalk with clusters of fuzzy half-inch brown structures (side view below). Each of these is a cup-like calyx, made of sepals that protected the sage's flower petals as they formed.

.

.

.

.

Please report your

Please report your