|

|

|||

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

|

|

THE ARTSY SIDE OF INSECT DAMAGE

By the time August rolls around at Hilton Pond Center, it's difficult along the trails to find woody or herbaceous plants whose foliage is intact. Weather in the form of windstorms, hail, and even heavy rain has abused tender green leaves and sometimes shredded them, but by far the greatest damage is done by hordes of ravenous insects that munch and chew on everything from blades of grass to the topmost leaf on our canopy trees. Instead of entire, well-formed leaves, these plants bear tattered greenery that--in some cases--barely retains enough surface to continue with photosynthesis. We understand fully why our high school students often had trouble putting together acceptable leaf collections in autumn; they'd have been much better off to compile one in late spring when foliage was fresh and new and unmarked by various invertebrate herbivores. Of course, had our students been interested in compiling a leaf collection from an artistic point of view instead of being scientifically descriptive, they could have looked at the artsy side of insect damage.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Perhaps the most common and most easily noticed insect-induced damage at Hilton Pond Center isn't all that aesthetic; it happens when voracious caterpillars of many moth and butterfly species take big bites from the edges--or centers--of leaves. For example, the inch-long larva of the Banded Tussock Moth, Halysidota tessellaris (above), consumes a wide assortment of tree leaves--from ashes to oaks and walnuts to willows. Looking like some sort of ornately costumed Japanese kabuki dancer, this fuzzy caterpillar grazes on whatever woody plant foliage suits its taste, leaving unartistic jagged holes wherever it goes.

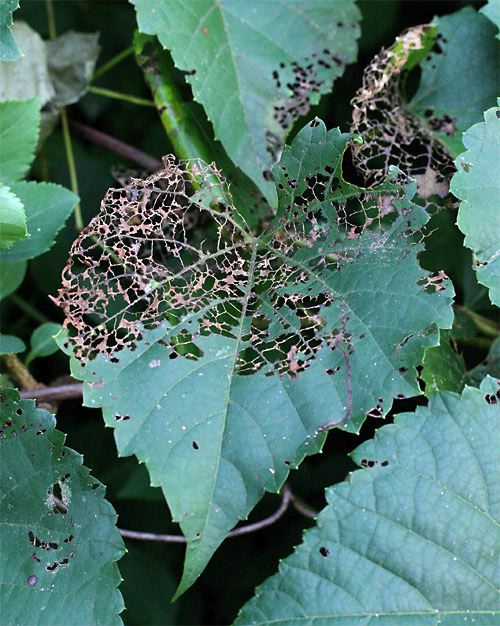

This week as we strolled around the Center we saw plenty of examples of what at first glance looked like vegetative destruction, but that--upon closer examination--did reveal a certain beauty not seen in a complete leaf. For example, a wild grapevine (above) had been chewed extensively by Japanese Beetles that removed much of the blade; only larger diagonal veins and a network of smaller connectors remained where these non-native insects filled their bellies.

In closer view, this beetle-ravaged leaf of the grape took on a different appearance (above)--an abstract art form just as attractive as any lace doily, crocheted shawl, or filigreed gold jewelry. This process in which the leaf blade is eaten away with only vascular tissue remaining is known as "skeletonization"--a sure sign hungry insects have been chowing down on cellulose and chlorophyll. Artsy, yes, but not very healthy for the leaf.

A little further down the trail we encountered a small Greenbrier vine whose leaves looked as if they had been spattered by whitewash (above). More than half of one leaf's upper surface bore little circular white dots about an eighth of an inch in diameter, each with a tiny tan center that was sometimes surrounded by concentric circles of white.

When took this sample back to the lab and examined it through our zoom macro lens, the leaf again took on a very different, artistic appearance. The veins became three-dimensional mountain ridges, and the white dots granular and almost fuzzy. Because of their non-overlapping placement, our first thought was these white dots had been caused by the larvae of almost microscopic insects--possibly wasps or flies--whose mothers stabbed the upper epidermis and laid eggs within the middle layer of the leaf. The brown mark would in part be a puncture-wound scar caused by each female's ovipositor. After hatching, larvae would develop in the leaf itself, their bodily excretions causing the leaf to discolor. Having explained THAT scenario, we must also offer a disclaimer: It may be the spots are actually some sort of fungus or mildew, but we don't understand why that sort of growth wouldn't overlap on the leaf's top surface. Without access this week to a compound microscope, we can't examine the leaf more closely to solve this little mystery. In either case, the damaged leaf is still pleasing to the artistic eye; the jury is out on what caused the white spots, so feel free to send us a note at INFO if you've got a more definite explanation.

An American Holly provided the next example of artistic insect damage. On one small tree growing at the very edge of Hilton Pond, we spied an unusual holly leaf that was very different from its smooth green neighbors (above). This one looked like someone had dripped yellowish wax along its top surface, creating a meandering series of curvy lines.

Back in the lab, this American Holly leaf looked almost like a piece of modernistic jewelry--a green pendant overlaid with sinuous trails of light gold. Each convoluted line was the work of a leaf miner--one of many kinds of insect larvae that dwell in the palisades layer between the leaf's upper and lower epidermis. Leaf miners can be the young of moths, sawflies, beetles, weevils, and flies--all of whose larvae tunnel about within the leaf while eating its living tissue. The tunnels are sometimes called "serpentine mines." Agromyzid flies are among the most common leaf miners in native hollies.

We were impressed by the artistic aspects of insect damage on the holly, grape, and greenbrier, but for us the most aesthetic example of herbivory came when we found a White Oak leaf (above) with what appeared to be off-white splotches--areas that almost looked like bird droppings. When we held the leaf up to the sky, we could see the splotches weren't droppings after all, but translucent areas that let through the light.

When we examined the leaf with the macro lens we were enthralled to see living green cells--complete with chloroplasts--as well as white, empty cells whose contents had been consumed completely, leaving only a maze of cell walls (above). Looking closely at both surfaces of the leaf, we could see the dark green epidermal cells on the top were still intact, while the bottom epidermis was gone. This was the work of caterpillars whose rasping mouth parts ground away the undersurface as they consumed the nutrient-rich cytoplasm of exposed cells. Apparently caterpillars dine on the leaf's bottom surface, where epidermal cells aren't as stout and where larvae are less obvious to predators such as birds.

At even higher magnification (above), the oak leaf's white areas resembled maps we've seen of hopelessly crowded subdivisions, with irregularly shaped lots accessible from winding roads (subveins) that eventually lead to superhighways (major veins). However, rather than ponder how much environmental havoc would be wrought by such a residential project, we'd rather just gaze at the photo above, marvelling at the intricate design of the leaf--AND the artsy side of Hilton Pond insect damage that's visible on nearly every sprig of summer foliage.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

Comments or questions about this week's installment?

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond." (Please see Support if you'd like to make a gift of your own.)

IMPORTANT NOTE: If you ever shop on-line, you may be interested in becoming a member of iGive, through which nearly 700 on-line stores from Barnes and Noble to Lands' End will donate a percentage of your purchase price in support of Hilton Pond Center and Operation RubyThroat. We've just learned that for every new member who signs up and makes an on-line purchase within 45 days iGive will donate an ADDITIONAL $5 to the Center. Please sign up by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless and important way for YOU to support our work in conservation, education, and research. "This Week at Hilton Pond" is written & photographed You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use our on-line Hilton Pond Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to |

Please report your

Please report your