|

|

|||

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

NOTE 1: We spent three weeks banding hummingbirds in Costa Rica in early 2008. The following account is for Week One. Accounts are now posted for Week Two and Week Three. A final report will discuss migration of Ruby-throated hummingbirds in the Neotropics.

NOTE 2: Three more nine-day hummingbird expeditions are scheduled for 2009: 24 January-1 Feb, 3-11 Feb, and 13-21 Feb. For more information see 2009 Hummingbird Expeditions and contact EDUCATION.) COSTA RICA HUMMINGBIRDS 2008: Thanks to word-of-mouth advertising and presentations we've given around the country during the past 12 months, our two eight-day Costa Rica hummingbird expeditions filled quickly for 2008. We were pleased this year's participants already knew about Hilton Pond Center and Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project and of successes achieved during our first four trips into the tropics. This year's enrollees were eager to become part of the only systematic study of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, Archilochus colubris, on their wintering grounds in Latin America. Our primary study locale in Costa Rica is Guanacaste Province in the northwestern quadrant of the country (see map at right); this region along the Pacific coast resembles western Texas and is drier, hotter, and less buggy than Caribbean and Upland Regions most tourists visit. Of the 50 or so hummingbird species found in Costa Rica, only about eight occur in Guanacaste--where ruby-throats find grassy, treed savannahs and dry forest edges to their liking. Ernesto Carman Jr., our in-country bilingual guide since the beginning, is an exceptionally knowledgeable, sharp-eyed, keen-eared, and likeable young naturalist who discovered Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in relatively high concentrations on Aloe Vera plantations near Liberia, Guanacaste's provincial capital. These aloe plantations (below) have been our destination for field studies each winter since December 2004.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center This year (2008) our own Costa Rica journey started a few days ahead of the rest of the team when we flew out of Charlotte NC on a non-stop flight to San Jose. There we were met by Ernesto and his long-time girlfriend Elaida Villanueva Mayorga, an accomplished naturalist herself and in-country educator participant during our first expedition in 2004.

DAY ONE ALPHA (25 Jan): As dawn broke on Day One, the advance team (Ernesto and expedition leader Bill Hilton Jr.) arose with excitement over the prospect of yet another annual try at banding Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in Costa Rica. After a sumptuous breakfast at Buena Vista Lodge, our temporary bus driver took us to the Aloe Vera fields, where we were elated to find a suitable number of tall yellow aloe flower stalks that have proved attractive to ruby-throats. We also checked out our favorite old Jocote, Spondias purpurea, the tree that was a life-saver in 2004-2005. During that first winter we went to Costa Rica "too early"--the day after Christmas--and, it turned out, BEFORE any aloe was in bloom. That meant our first two groups had to work exceptionally hard over 16 days to band just 15 birds--nearly half of which we caught in a pull-string trap hoisted to the top of the Jocote tree. We were quite surprised this year to find a new concrete house had been built in the open lot behind the Jocote (above), but when we told the new residents the history of our work they allowed us to hang a sugar water feeder in the tree--in anticipation of perhaps trapping more hummers at that locale in 2008.

After our scouting work was complete our sleek and shiny air conditioned bus took the scouting team to the Liberia airport, where we stationed ourselves outside the terminal until afternoon flights began to arrive. It's always fun to greet the next team of participants as they make their way through customs and immigration. We knew several arrivals from Elderhostel programs we gave last year in West Virginia--or from programs elsewhere--and the rest recognized us by our Operation RubyThroat T-shirts and signs. Despite well-laid plans, however, two people missed connections and ended up being driven by bus from San Jose to Buena Vista Lodge in time for the evening orientation meeting. Luggage failed to arrive for "only" one person.

Following our sumptuous airport lunch the new arrivals drove up the mountain and settled in at Buena Vista Lodge, where something unusual happened. As we were walking toward our usual 5 p.m. gathering at Mirador--a sunset lookout that faces due west over the Pacific Ocean--we happened upon a good-sized bird lying in the middle of the road. We stooped to gather it up and realized it was a Blue-crowned Motmot, Momotus momota (above), apparently stunned from flying into a dining hall window. We avoided the bird's strongly serrated bill and carried it for an impromptu "show-and-tell" at the lookout, where its colors rivaled those of the setting sun.

Team members and other guests alike were mesmerized by this hand-held bird's attributes--many of which would not be as noticeable in the bush. Shortly after our demonstration, we returned with our captive motmot to the area where we found it, and everyone watched happily as the bird flew to a nearby tree and began preening its distinctive, pendulum-shaped tail (above). We saw this same motmot calling later in the week, so it appeared to have survived the window strike in good shape. We took this first Costa Rica 2008 bird-in-the-hand as a sign we would have great successes in the field in days to come.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center During our first four hummingbird expeditions, each team was in Costa Rica for eight days. However, Days One and Eight were always travel days, Day Two was a scouting day, and we also took an all-day trip to a nearby national park. That left a maximum of four days for field work, so in 2008 we arranged a different schedule. Since the advance team had already scouted aloe fields and found suitable study sites, this year's Week One folks could hit the ground running on Day Two; furthermore, by shuffling but not cancelling other activities we were able to plan on SIX mornings in the field--a significant increase in time devoted to observation and banding. In keeping with our tradition of naming each of our previous teams--The Pioneers and The Second Wave (2004-2005), The Oh-Sixers (2006), and The Lucky Sevens (2007)--we decided, with their permission, to call this year's first group "Krazy '08s Alpha" (group photo above). Members of Krazy '08s Alpha were Glenn & Juli Dulmage (Chestertown MD), David & Linda Egeler (Elk Rapids MI), Carol Foil (Baton Rouge LA, and moderator for the HUMNET-L listserv), Marilyn & Bill Hinze (West Lafayette IN), Gordon Page (Tappahannock VA), Herb & Rosemarie Wahaus (Lake Wylie SC), and Evelyn & Tom Walder (Newfane NY). A while back we predicted--correctly, we might add--that these citizen scientists from across the U.S. would end up working at least as hard and as conscientiously as their predecessors.

DAY TWO ALPHA (26 Jan): After an early breakfast on 26 January at Buena Vista Lodge--situated about 2,400' up the side on Rincon de la Vieja volcano--Krazy '08s Alpha boarded the bus for their first ride to the aloe fields. The plantation is situated on mostly level ground about 600' above sea level nearly ten miles north of Liberia. The bus trip down crossed numerous hills and valleys and passed a variety of habitats, including extensive grazeland populated by long-eared, hump-backed cattle called Zebu, Bos primigenius indicus (bull, above). These dewlapped beef producers--of which several strains can be found in Guanacaste--are better adapted to tropical climates than temperate zone breeds such as Black Angus.

During the bus ride to and from the study site the team always had binoculars and cameras at the ready in case we encountered interesting birds--perhaps a male Hoffman's Woodpecker, Melanerpes hoffmannii (above), a caracara, or a toucan or two. (The pictorial section at the end of this essay includes several photos taken along the route.) In any case, the trip from lodge-to-aloe took about an hour, a little longer coming back uphill. The aloe fields near Liberia are extensive. The first (Aloe Vera One, or AV1) is just north of the road to Buena Vista Lodge and has never had enough flowers to make it even marginally attractive to ruby-throats (or banders).

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Between that first bird--a second year male with an incomplete red gorget--and an adult female netted at 11:02 a.m., we banded nine birds on our first field day in late January 2008. This in itself would have been a good start, but just as we were preparing to close down at 11:15 a.m., the almost-unimaginable happened: Ernesto retrieved a hummer from a net and, upon returning to the banding table, realized it was already banded. A quick check showed its aluminum anklet was inscribed with C51582 (above). Our records showed this was a female we had banded LAST YEAR on 5 February 2007 in the net right beside the one where we recaptured her this year! Thus, on our very first field day in 2008 we re-caught a bird that indicates female Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--like the male from 2006 we re-caught in 2007--likewise have site fidelity on their tropical wintering grounds. Obviously, the Krazy '08s Alpha members were pretty pleased with this discovery . . . to say nothing of the rest of their first day efforts.

DAY THREE ALPHA (27 Jan): Our second day of banding in AV3 was even more productive than the first, except we didn't net any recaptures from previous years. Nonetheless, from 7:18 am through 10:40 a.m. we netted and banded 11 new ruby-throats, bringing the two-day total to 20--significantly more than the 15 caught by both groups together in 2004-2005. On Day Two we also netted two other Neotropical migrant species from North America: A second-year male Orchard Oriole (above) and two second-year Barn Swallows.

DAY FOUR ALPHA (28 Jan): At first glance, the results of our third day at AV3 looked pretty low with "only" seven RTHU banded, bringing the Krazy '08s Alpha total to 27. Numbers can be deceiving, however. We undoubtedly would have caught even more hummingbirds except this was the day Orchard Orioles decided to invade AV3. Following our third morning in the field, the group boarded the bus to ride into Liberia for a fresh seafood lunch at a local Chinese restaurant, and to shop for souvenirs in the provincial capital. Highlight of the "big city" excursion for many folks was a shaved ice concoction, loaded with fruit juice and evaporated milk and prepared from a push cart by an elderly tico (native Costa Rican male, above left). Yummy!

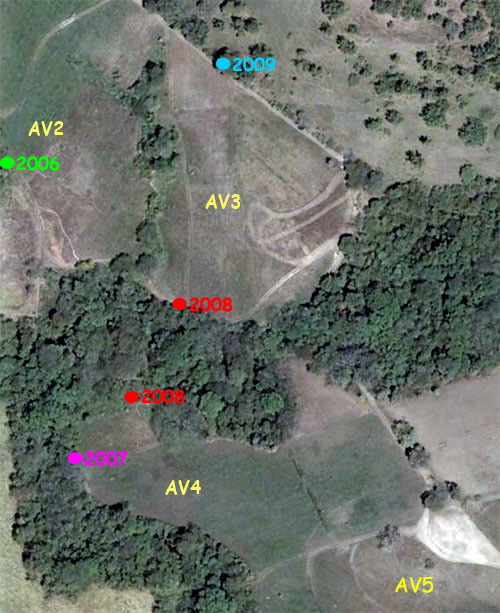

DAY FIVE ALPHA (29 Jan): After nearly being swallowed up by that horde of Orchard Orioles on 28 January, we decided on Day Five to move our netting operations to AV4 (above), the next aloe field to the south. (We had planned to do so anyway, wanting to sample the RTHU population in a new locale in which we'd never worked.) This field was larger, had several dense areas of aloe flowers, and included different vegetational edges than AV3. (See GoogleEarth image, below, of the aloe fields in which we worked in 2008; banding table positions are marked with red dots.)

The move to AV4 turned out to be a wise choice; on 29 January we caught 17 ruby-throats from 7:55 a.m. through 10:55 a.m. and only had to remove one Tennessee Warbler from the nets. That brought our number of RTHU in 2008 to 44, easily surpassing the 2007 total of 31.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center; photo above © Glenn Dulmage We always try to involve local residents in our Operation RubyThroat endeavors in Costa Rica. Through the years we've developed friendships with several youngsters from the nearby town of Canas Dulces, where parents encourage them to watch us as we work catching hummers and other birds. Because we're in Guanacaste during the "winter vacation" when school is not in session, we sometimes see elementary-age kids going into the aloe fields to work with their fathers. The inquisitive youngster above--probably less than eight years old--took time from his aloe-related chores to marvel over a Groove-billed Ani we had just netted. DAY SIX ALPHA (30 Jan): Our next day in AV4 was impeded somewhat by an increase in wind on the study site; this caused nets to billow out and reduced their effectiveness. Nonetheless, we caught and banded eight RTHU, bringing the yearly total to 52--one more than the all-time record of 51 banded in 2006. Also netted that day were three other Neotropical migrants: One female Indigo Bunting, one female Blue Grosbeak, and a male Tennessee Warbler.

It should be noted that on 30 January two RTHU were captured not within AV4 but in a new net in the woods behind the banding table--a net deployed in a patch of red flowers (above). We believe this plant, a member of the Acanthaceae (Acanthus Family), is Aphelandra scabra--which has no common name of which we are aware.

We closed the nets a tad early this day for an afternoon trip to explore dry tropical forest habitat--both deciduous and evergreen--in Santa Rosa National Park, and to swim in the Pacific Ocean at Junquillal Beach marine sanctuary. At the latter we spotted scores of Magnificent Frigatebirds (above)--and a dozen or two Brown Pelicans--all feeding on surface fish in the bay. DAY SEVEN ALPHA (31 Jan): The final day in the field for Krazy '08s Alpha was our slowest, again due at least in part to wind. Oddly, after all those orioles and other species earlier in the week, we didn't catch any non-hummingbird Neotropical migrants. Two RTHU did hit the nets pretty early at 7:24 and 7:43 a.m., after which there was nothing until 10:25 a.m. when a third ruby-throat was snared. Three more hummers between 10:45 a.m. and 10:58 a.m. brought the day's total to six and the week's results to 58. Two of the RTHU were netted in the Acanthacean grove behind the banding table (see 30 January above).

During the morning we were honored by a visit from Brenneman & Karen Parker Thompson (above), whom we met at Buena Vista Lodge earlier in the week. In an "it's-a-small-world" connection, the Thompsons live about 30 miles from Hilton Pond Center--near Wing Haven garden and bird sanctuary in Charlotte NC, where Brenny is a realtor and Karen directs the United Family Service Domestic Violence Program.

The afternoon of Day 7 was devoted to our traditional horseback ride to the volcanic spa Buena Vista property. Historically we've found this to be a fun way to end a week of intensive field work and learning, so most participants saddle up good-naturedly and make the clippity-clop trip up the mountain (above). Like their predecessors, Krazy '08s Alpha group members bounced along the trail to the spa and then slathered each other with hot, gritty volcanic mud (below). This is a lot more fun than it sounds, especially when one squirts off the mud with freezing cold water and then jumps into a thermal pool for an hour or so of blissful relaxation.

The hard part of the this whole activity is getting out of the warm pool, getting dressed, and remounting our trusty steeds for the ride back--something, in retrospect, we wish we hadn't done. Several riders elected to forsake their horses and go back down the mountain in a tractor-drawn wagon, but the Fearless Leader of the Operation RubyThroat hummingbird expedition stayed on for the return ride via his trusty steed. About halfway back, the remaining half-dozen or so horses started to run, upon which the rider just ahead of Fearless Leader pulled hard right on his reins, jostling Fearless Leader's mount toward a tree. The horse and Fearless Leader's body went on the LEFT side of the trunk, while Fearless Leader's right leg went on the tree's RIGHT side. Ouch!

Needless to say, a half-ton horse moving at trotting speed and sending its rider into a tree means something has to give--and it wasn't the tree or the horse that suffered consequences. In fact, what gave was Fearless Leader's right ankle. Initial result: An ominous popping noise, immediate swelling, and considerable pain. Eventual diagnosis: A clean break of the fibula near the ankle joint. [PERSONAL NOTE: In the absence of on-site medical care Fearless Leader bit the bullet, got off his horse (above), boarded the tractor-pulled wagon for the remaining miles back to the lodge, and then gutted out the next two weeks on ibuprofen and a pair of crutches before returning to Hilton Pond to visit an orthopedic surgeon--who immediately put Fearless Leader in a walking boot to be worn for a couple of weeks. Fearless Leader is eternally grateful Ernesto Carman Jr. brought his new car on this year's expedition and that each day 'Nesto willingly offered shuttle service between the dining hall, lodging, and other sites. It was also great that our new group that came in for Week Two provided cheerful assistance, but more about that in a later installment.]

DAY EIGHT ALPHA (1 Feb): With 58 banded Ruby-throated Hummingbirds to show for their six days in the field, Krazy '08s Alpha arose a little later than usual on their last morning in Costa Rica, ate breakfast, finished packing, and then boarded the bus for their final trip down the mountain. Along the way, official Trip Lister Carol Foil read off the names of all bird species we had seen during the week--an impressive total of more than 100 Costa Rican resident birds and Neotropical migrants. Most group members went on to the Liberia airport (above) for an outgoing flight back to the U.S., but two couples stopped and rented cars and stayed in Costa Rica on their own for a few more days. Bus driver Whiskers, local guide Ernesto, and gimpy Fearless Leader went back into Liberia to eat lunch and to buy a plastic tub in which Fearless Leader could soak his foot upon returning to Buena Vista Lodge later in the afternoon--and on numerous days before and after the new group of participants arrived on 3 February. KRAZY '08s ALPHA GROUP (Week One) RESULTS During six days of field work in Costa Rica in late January 2008, Krazy '08s Alpha had the most successful capture week to date with 58 ruby-throats banded. (CAVEAT: Previous expeditions had three or four days in the field while the 2008 group had six.)

As shown by Table 1 (above), more RTHU males (36) were banded than females (22). The 32 males with incomplete red gorgets were youngsters that must have hatched in 2007 in the U.S. or Canadian breeding grounds, so they were classified as SY or Second Year birds, AKA "juveniles". (The SY male in the photo below right has a partly red gorget and very dark greenish-black streaking on its throat--both signs of a juvenile male.) It should be mentioned that all birds become "a year older" on 1 January. However, three males with full red gorgets--listed above as ASY or After Second Year birds--provided one additional hint as to their age. Here's how: RTHU go through a complete molt on the wintering grounds, replacing all body plumage (including the throat) and all wing and tail feathers. Curiously, when a "juvenile" RTHU male brings in his first adult plumage, the adult primary wing feathers are significantly SHORTER than the juvenile primary wing feathers they replace. Thus, when we measure the wing chord of a juvenile male RTHU, it usually falls in the range of 40-42mm, while the typical adult male's wing measures about 36-39mm. All three males we classified as ASY had OLD, faded primaries that measured in the 36-39mm range of adults, so we knew these birds had to be at least two years old, i.e., they hatched in 2006, or earlier, hence After Second Year. (Based on our work with RTHU that have returned to Hilton Pond Center in later years, it appears females of the species also have shorter wing chords from juvenile to adult, but because of a greater range in measurements---40-46mm--and possible overlap, we're not as confident in using wing chord to age females.)

In the photo just above, an adult male is bringing in a new #7 primary, but the three outermost primaries (8-10) are old and faded AND the wing chord is less than 39mm--confirming this as an After Second Year bird. (Don't be alarmed if you have to read this explanation several times; ageing birds is a concept about which experienced banders sometimes have to think twice. Even though the scheme is complicated, it really does make sense and is worth the effort to learn it; knowing the age of banded birds gives us a more complete understanding of the population make-up for any given species.) Wing molt, by the way, is not something one would normally observe on RTHU in North America--except in those relatively few birds that overwinter here, primarily in Gulf and Atlantic Coast states.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center If we refer again to Table One and lump our banded ruby-throats together by sex rather than age AND sex, we see Crazy '08s Alpha helped net 36 males (62%) but only 22 females (38%, above), a 3:2 male:female ratio. (The ratio was closer to 1:1 among RTHU captured in AV3; our work in AV4 was what skewed the overall ratio toward the male side.) Our initial response was that an abundance of males in AV4 seemed unusual, so we were quite interested to see what would happen when we repeated our efforts in AV3 and AV4 during Week Two after Krazy '08s Alpha was replaced by a new group of field workers. (The next installment of "This Week at Hilton Pond" includes those results.) We should mention that all Ruby-throated Hummingbirds we band in Costa Rica are weighed; measured for length of tail, culmen (central ridge of upper mandible), and wing chord; Regardless of actual numbers, we were quite pleased with the work of Krazy '08s Alpha. We especially were enthused by their recapture of #C51582, the After Second Year returnee that finally confirmed site fidelity on the wintering grounds for female RTHU. We will never forget the cordiality of the 12 Krazy '08s Alpha group members and their contribution to Operation RubyThroat's on-going efforts to describe and understand Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in the tropics--where these little migrants spend the OTHER half of the year. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center KRAZY '08s ALPHA SCRAPBOOK In addition to banding more Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in Week One than ever before, we also netted a great many Neotropical migrants and resident Costa Rican birds. Thus, our Krazy '08s Alpha scrapbook is considerably bigger than in past years. We hope you'll enjoy the following images of people, places, and wildlife.

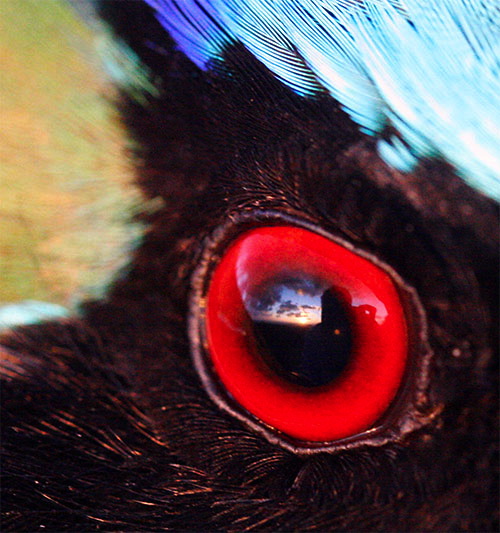

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Despite waning light at dusk--see the sunset reflected in the pupil of the eye below--we just couldn't stop taking photos of the Blue-crowned Motmot we picked up after it was stunned from striking a window at Buena Vista Lodge.

The big eye of the Blue-crowned Motmot (Momotidae) undoubtedly helps it spot its prey--usually small lizards and mammals, plus large insects. Non-migratory Blue-crowned Motmots can be found from Mexico to South America.

We also saw the Turquoise-browed Motmot, Eumomota superciliosa (above), at several locations in Guanacaste Province; this 13" species lacks the dark central head spot characteristic of the somewhat larger (16") blue-crowned. The individual in the photo above--shown wrestling with a mouthful of grasshopper or katydid--frequented the same wooded area where we found its window-strike relative. Turquoise-browed Motmots have the most pendulous tails of the six Costa Rican motmot species; these appendages are sometimes said to be "raquet-tipped."

On their first night at Buena Vista Lodge, Krazy '08s Alpha was treated to the sight of a nearly full Moon (above) rising over Rincon de la Vieja. They almost missed the spectacle, however, because of heavy, fast-moving clouds hanging over the volcano on the Caribbean side. Unlike Year One when we went to Costa Rica in late December 2004, our late January 2008 expedition experienced no rain on the mountain and did not have to endure major nighttime wind gusts.

Black Iguanas, Ctenosaura similis, whose dewlaps (throat flaps) lack spines, are ubiquitous in Guanacaste Province, from the seashore to volcanic slopes. The three-foot-long individual above hung around outside our Cabin #82 at Buena Vista Lodge, sunning itself and--if disturbed--skittering along the trail and quickly climbing a nearby tree at surprising speed. The Green Iguana, Iguana iguana--sometimes kept as a house pet in the U.S.--does have dewlap spines and is far more common on the Caribbean side of Costa Rica.

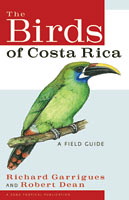

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The first non-hummingbird we caught in the Aloe Vera fields in 2008 is pictured just above. If your only book on Costa Rican birds is the old standard 1989 field guide by Stiles and Skutch, don't bother trying to find this species therein because it's not listed.

Pictured above is another non-hummingbird we netted in AV3 during Week One. If you're like most North American birders, you probably thought "Great Crested Flycatcher" upon viewing the photo, but that would be incorrect. The Great Crested Flycatcher does occur in Guanacaste as a Neotropical migrant, but several other resident flycatcher species make identification problematic. One secret is to look at the lower mandible, which in the great crested is pale for at least half its length; the bird above has a dark lower mandible. This narrows the identification to Brown-crested Flycatcher and Nutting's Flycatcher, which look almost alike. The former has a gray-brown rump, the latter a rump of cinnamon. Since our bird-in-hand did have a gray-brown rump, that made it a Brown-crested Flycatcher, Myiarchus tyrannulus.

The tiniest resident hummer we've encountered on our study site in Guanacaste is Canivet's Emerald, Chlorostilbon canivetii, a 3" species even smaller than our diminutive 3.5" Ruby-throated Hummingbird. Males are emerald green all over, while females (above) superficially resemble ruby-throats--except for the emerald's prominent facial pattern and pink-to-red lower mandible with a black tip. The "old" Fork-tailed Emerald was recently split into two new species--Canivet's Emerald and the Garden Emerald, C. assimilis--based on geographical and morphological differences; among other things, Garden Emerald has a bill that is completely black. Older field guides do not reflect this taxonomic change and some ornithologists still do not accept it. The bird in the photo above is an apparent immature, based on a bill that is quite corrugated--not smooth as in adults--and because of heavy brown edging on otherwise green head feathers.

Noticeably larger than Canivet's Emerald was the 4" Cinnamon Hummingbird, Amazilia rutila (above), a resident Costa Rican species limited primarily to Guanacaste. Like several hummers in the aloe fields, this bird also has a red bill with black tip, but both sexes are monomorphic--they look alike--and their overall appearance gives the species its common name. Cinnamon is indeed the prominent color on the bird's throat, breast, belly, undertail coverts, and tail. This species was one of the most commonly observed hummingbirds in our aloe fields and we netted several individuals--include females with featherless incubation patches on their bellies that indicated they were active breeders.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Among the most commonly HEARD large mammals in Guanacaste were Mantled Howler Monkeys, Alouatta palliata, which the Krazy '08s Alpha group encountered in several habitats during our Costa Rica stay. There was nothing quite like running mist nets in the aloe fields each morning while listening to two competing howler monkey males boom back and forth at each other with deep-throated territorial calls. Along the way to and from Buena Vista Lodge to the aloe fields we always crossed a stream that has cut through limestone rock to form a hundred-foot-tall vertical cliff festooned with orchids, ferns, lichens, and other interesting vegetation. During each excursion to Costa Rica, we stop at least once at "The Wall" to see what we can find and to relax in the coolness of this interesting natural locale. This year, we were surprised to spot a troop of howler monkeys exploring the cliff, including a female with young (above). This particular adult was not disturbed in the slightest by our presence--in fact, she and her offspring both seemed more than a little curious as the pair dangled precariously from exposed tree roots high above our heads. The female engaged in an interesting behavior that involved licking the exposed cliff wall where it was stained white; we hypothesized the stain came from salts leached from the rock and that helped meet the monkey's dietary mineral needs.

While watching the monkeys at The Wall, sharp-eyed guide Ernesto Carman Jr. noticed something else on the vertical cliff, tucked under a slight overhang. It looked like a little volcano made of was a pile of light fluffy material (above), with a tunnel going into it. Excitedly, Ernesto suggested it might be the nest of the Lesser Swallow-tailed Swift, Panyptila cayennensis, a black-and-white Central American relative of the Chimney Swift that breeds across North America. What was so exciting about this observation is that the rather uncommon Lesser Swallow-tailed Swift is not known to nest in central Guanacaste Province, preferring instead to breed along the Caribbean and south Pacific coasts of Costa Rica and in the central volcanic ridge. We made a note to be sure to investigate the nest during Week Two to try to determine if it was under construction and/or to spot the actual homebuilders.

Our one and only encounter with a hand-held Groove-billed Ani, Crotophaga sulcirostris (above), was all we needed to convince us this shiny black bird was capable of biting hard. After netting this 12-inch-long member of the New World Cuckoo Family (Cuculidae), we held it aloft for Krazy '08s Alpha photographers, at which point the bird clamped down hard on--and drew blood from--our finger webbing. We learned later from Elaida, Ernesto's girlfriend, that to be bitten by an ani puts one pretty far down on the pecking order in Costa Rica.

We've only handled six Baltimore Orioles, Icterus galbula, during our 27 years at Hilton Pond Center, so we were pleased to net two adult males (above) of this species on 28 January in Aloe Vera Field #3. Baltimore Orioles are common and widespread winter residents in Costa Rica. Within a few months they'll be making their way back toward their breeding grounds, primarily in eastern North America.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Perhaps the most spectacular hummingbird we've ever handled showed up in a net on the same day we caught the bevy of orioles and other Neotropical migrants. Examining all these birds almost consumed our lunch break, but it was worth it to be able to examine and photograph the first male Blue-throated Goldentail, Hylocharis eliciae, we had ever seen. The colors on this ruby-throat-sized hummer were simply breathtaking; the images above and below are our feeble attempt to represent the many hues of blue and green and gold that adorned this hummer.

As with several Guanacaste hummingbird species, the Blue-throated Goldentail's bill was red with a black tip (above). The color and wide base of this bill reminded us of the Broad-billed Hummingbird, Cynanthus latirostris, we captured earlier this year near Charleston--South Carolina's first banding record for that species. The two hummers, although somewhat related, are in different genera.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Blue-throated Goldentail is a perfect name for this Costa Rican hummingbird, since the colors of those two body regions are particularly noticeable. However, the tail is even brighter gold from the underside (above) than on its dorsal surface, we suspect because the male faces the female during courtship such that the ventral side of the tail is more visible.

The White-collared Seedeater, Sporophila torqueola, occurs widely in Costa Rica, but it is the only seedeater in the country with wing bars. The male (above) is in non-breeding plumage; we suspect the brown tips of the head feathers will wear off gradually, revealing a jet black that will be more attractive to potential mates. As might be anticipated from this bird's conical bill, it is in the Emberizidae--the family that includes our North American sparrows, but NOT our buntings and grosbeaks.

The male Blue-black Grassquit, Volatinia jacarina (above), is another common Costa Rican emberizid. It, like the White-collared Seedeater, has brown plumage tips that wear off in time for the breeding season, in this case exposing metallic blue-black feathers. Blue-black Grassquits are one resident bird we've caught every year in the aloe fields.

After three years of trying, on 29 January 2008 we finally netted a Clay-colored Robin, Turdus grayi. This is Costa Rica's national bird, although it may be the most nondescript national bird of any country. Sexes are alike with uniform dull, brown plumage, orangey-brown eye, and greenish-yellow bill. This sedentary species is closely related to our American Robin, T. migratorius. Garrigues & Dean say the species was selected as Costa Rica's symbol because from March through June it "tirelessly whistles melodic phrases."

From butterflies to beetles to walking sticks, there are plenty of interesting insects in Costa Rica, but this year we scarcely had time to make images of them. This was our busiest net year ever, so we spent most of our time banding Ruby-throated Hummingbirds and photographing other Neotropical migrants--plus the great variety of resident birds we encountered. A tiny insect--a half-inch-long Praying Mantis nymph (above)--did visit us one day at the banding table, so we managed to snap a few exposures as it posed on our knuckle.

One of the more distinctive birds we netted in the aloe fields was a ten-inch-long White-necked Puffbird, Notharchus macrorhynchos (above)--a big-billed, big-headed relative of the kingfishers. Puffbirds have their own family (Bucconidae)--the kingfishers are in Alcedinidae--but the resemblance is unmistakable. That said, kingfishers have straight, tapered bills while a puffbird typically has a stout bill with a hook that belies its predatory habits. (Yes, puffbirds in-the-hand DO bite!)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although Ruby-throated Hummingbirds on our Guanacaste study site spent considerable time feeding in on Aloe Vera, they also frequented many other food sources. (Our write-up for Week Three will deal with some of the other nectar sources.) One especially popular nectar plant was the Inga, Inga edulis, a canopy tree whose feathery white blossoms attracted bees, butterflies, and several hummingbird species. Above, a ruby-throat in primary wing feather molt hovers at an Inga flower before diving in for a sugary meal.

Costa Rica has more than two dozen species of doves and pigeons--twice a many as in the entire U.S.--and it takes a while to learn all of them. One of the most common species in Guanacaste was the Inca Dove, Columbina inca (above), a small eight-inch species identifiable by scale-like feathers on head, wings, back, and breast, and by its bright rufous primary feathers.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although we netted no parrots on our Aloe Vera study site, we did observe several species in Costa Rica--including this Yellow-naped Parrot, Amazona auropalliata (above), photographed through the bus window glass as it emerged from a hole in a dead-standing palm tree. Parrots do not excavate their own cavities and often occupy abandoned woodpecker nests. This species, uncommon in Guanacaste, declined precipitously in the past half-century because of the cage bird trade. Now under protection, it appears to be making a slow but positive comeback.

Ruby-throated Hummingbirds and Orchard Orioles weren't the only organisms using Aloe Vera fields in Guanacaste. Inside an aloe flower cluster we found this little half-inch unidentified caterpillar with big black false eyespots that may deter predators.

Almost every evening at 5 p.m., members of Crazy '08s Alpha gathered at Mirador, a promontory at Buena Vista Lodge that looked west across Guanacaste Province. There, as they watched the sun sink into the distant Pacific Ocean, group members talked about events of the day--from catching record numbers of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds to encountering some new tropical plant to watching the antics of Mantled Howler Monkeys. We're hopeful as they watch future sunsets back in their hometowns that they'll never forget their Costa Rica experience and their valuable contributions to the goals of Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center NOTE 1: We spent three weeks banding hummingbirds in Costa Rica in early 2008. The above account is for Week One. Accounts are now posted for Week Two and Week Three. A final report will discuss migration of Ruby-throated hummingbirds in the Neotropics. NOTE 2: Three nine-day expeditions are scheduled for 2009: 24 Jan-1 Feb, 3-11 Feb, and 13-21 Feb. For more information see 2009 Hummingbird Expeditions and contact EDUCATION.)

Comments or questions about this week's installment?

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond." (Please see Support if you'd like to make a gift of your own.)

If you ever shop on-line, you may be interested in becoming a member of iGive, through which nearly 700 on-line stores from Barnes & Noble to Lands' End will donate a percentage of your purchase price in support of Hilton Pond Center and Operation RubyThroat. For every new member who signs up and makes an on-line purchase iGive will donate an ADDITIONAL $5 to the Center. Please sign up by going to the iGive Web site; as of this week, 117 members have signed up to help Hilton Pond Center. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our work in conservation, education, and research. "This Week at Hilton Pond" is written & photographed You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use our on-line Hilton Pond Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to |

|

Make direct donations on-line through

Network for Good: |

|

|

LIKE TO SHOP ON-LINE?

Donate a portion of your purchase price from 700+ top on-line stores via iGive: |

|

|

Use your PayPal account

to make direct donations: |

|

| The highly coveted Operation RubyThroat T-shirt --four-color silk-screened--is made of top-quality 100% white cotton--highlights the Operation RubyThroat logo on the front and the project's Web address (www.rubythroat.org) across the back.

Now you can wear this unique shirt AND help support Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project and Hilton Pond Center. Be sure to let us know your mailing address and adult shirt size: Small (suitable for children), Medium, Large, X-Large, or XX-Large. These shirts don't shrink! Price ($21.50) includes U.S. shipping. A major gift of $1,000 gets you two Special Edition T-shirts with "Major Donor" on the sleeve. |

Need a Special Gift just in time for the Holidays? (Or maybe you'd like to make a tax-deductible donation during 2007) If so, why not use our new handy-dandy on-line Google Checkout below to place your secure credit card order or become a Major Donor today? |

|

|

|

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS WEEK:

|

OTHER NATURE NOTES OF INTEREST NOTABLE RECAPTURES THIS WEEK (with original banding date, sex, and current age) American Goldfinch (4) All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

|

|

|

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) Up to Top of Page Back to This Week at Hilton Pond Center Current Weather Conditions at Hilton Pond Center |

You can also post questions for The Piedmont Naturalist |

Join the |

Search Engine for |

|

|

Best Buy Coupon

Since 2004 our teams have been observing non-breeding RTHU in Costa Rica, plus capturing, banding, and releasing these hummers as we try to learn more about migration and other behaviors.

Since 2004 our teams have been observing non-breeding RTHU in Costa Rica, plus capturing, banding, and releasing these hummers as we try to learn more about migration and other behaviors.

After spending the night at Finca Cristina, the Carman family's fully organic shade-grown coffee farm at Paraiso, we departed for Guanacaste in Ernesto's newly purchased used car--a vehicle that ended up getting much more use than we anticipated. (At left, Ernesto and his dad Ernie Carman--a former Boy Scout and U.S. Navy pilot--secure net poles to the roof rack, making expert use of the "barrel hitch" knot.) Almost six hours later we arrived at Buena Vista Lodge--our home away from home in Costa Rica--and turned in early, knowing next day we would need to scout aloe fields in the morning before meeting this year's first 12-participant group at the Liberia airport that afternoon.

After spending the night at Finca Cristina, the Carman family's fully organic shade-grown coffee farm at Paraiso, we departed for Guanacaste in Ernesto's newly purchased used car--a vehicle that ended up getting much more use than we anticipated. (At left, Ernesto and his dad Ernie Carman--a former Boy Scout and U.S. Navy pilot--secure net poles to the roof rack, making expert use of the "barrel hitch" knot.) Almost six hours later we arrived at Buena Vista Lodge--our home away from home in Costa Rica--and turned in early, knowing next day we would need to scout aloe fields in the morning before meeting this year's first 12-participant group at the Liberia airport that afternoon.

AV2--about a half-mile south of the Jocote tree--yielded a record-setting total of 51 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in late February 2006. AV2 had few blooms last year, so we skipped over to the adjoining AV3 and banded 31 ruby-throats in early February 2007. Of much greater importance, there we recaptured RTHU #C51517. This very special bird had been banded in 2006 in AV2 as a second year male; when we recaptured him at AV3 in 2007 he was in heavy gorget molt (above left) and became the FIRST Ruby-throated Hummingbird ever known to show site fidelity on the species' wintering grounds--just as they do during the breeding season here at Hilton Pond Center and elsewhere in the U.S. and Canada.

AV2--about a half-mile south of the Jocote tree--yielded a record-setting total of 51 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in late February 2006. AV2 had few blooms last year, so we skipped over to the adjoining AV3 and banded 31 ruby-throats in early February 2007. Of much greater importance, there we recaptured RTHU #C51517. This very special bird had been banded in 2006 in AV2 as a second year male; when we recaptured him at AV3 in 2007 he was in heavy gorget molt (above left) and became the FIRST Ruby-throated Hummingbird ever known to show site fidelity on the species' wintering grounds--just as they do during the breeding season here at Hilton Pond Center and elsewhere in the U.S. and Canada. Because AV2 was again low on flower production this year, once more we went straight to AV3. Fortunately our permanent bus driver, Guillermo--better known as "Whiskers" from his Pancho Villa moustache (right, photo by Carol Foil)--was willing to drive within a hundred yards of the study site, so upon arrival we unstrapped ten-foot-long net poles from the top of the bus and unloaded our gear for the short carry to AV3. There, after receiving initial instructions on how mist nets work, Krazy '08s Alpha set about deploying several 12-meter-long nets in the same positions used during last year's expedition. The group had barely begun their work when--at 7:50 a.m.--the first net we erected caught the first ruby-throat of 2008.

Because AV2 was again low on flower production this year, once more we went straight to AV3. Fortunately our permanent bus driver, Guillermo--better known as "Whiskers" from his Pancho Villa moustache (right, photo by Carol Foil)--was willing to drive within a hundred yards of the study site, so upon arrival we unstrapped ten-foot-long net poles from the top of the bus and unloaded our gear for the short carry to AV3. There, after receiving initial instructions on how mist nets work, Krazy '08s Alpha set about deploying several 12-meter-long nets in the same positions used during last year's expedition. The group had barely begun their work when--at 7:50 a.m.--the first net we erected caught the first ruby-throat of 2008.

By day's end we had netted 17 of them in every conceivable winter plumage (after second year adult male, above). Oddly, the field guides say OROR are "rare" in winter (November through February) in Costa Rica, being found much more commonly during fall and spring migration. In addition to the glut of OROR, the nets pulled in numerous other Neotropical migrants: Three Tennessee Warblers, two adult male Baltimore Orioles, an adult male Yellow Warbler, and a female Painted Bunting adorned in cryptic green. Of these, we can confirm at least the orioles were after the same aloe nectar consumed by our sought-after Ruby-throated Hummingbirds.

By day's end we had netted 17 of them in every conceivable winter plumage (after second year adult male, above). Oddly, the field guides say OROR are "rare" in winter (November through February) in Costa Rica, being found much more commonly during fall and spring migration. In addition to the glut of OROR, the nets pulled in numerous other Neotropical migrants: Three Tennessee Warblers, two adult male Baltimore Orioles, an adult male Yellow Warbler, and a female Painted Bunting adorned in cryptic green. Of these, we can confirm at least the orioles were after the same aloe nectar consumed by our sought-after Ruby-throated Hummingbirds.

Our one "adult" male with a complete red gorget could have hatched in 2007 and might simply have been showing advanced molt, but he also could have hatched BEFORE 2007; to be safe he was classified as AHY or After Hatch Year.

Our one "adult" male with a complete red gorget could have hatched in 2007 and might simply have been showing advanced molt, but he also could have hatched BEFORE 2007; to be safe he was classified as AHY or After Hatch Year.

checked for body fat; and examined for molt--especially of the throat, tail, and primary feathers. Each bird is also color marked on the upper breast with harmless blue dye (left) to allow for further observations after banding and release. RTHU from Hilton Pond Center are marked with green dye.

checked for body fat; and examined for molt--especially of the throat, tail, and primary feathers. Each bird is also color marked on the upper breast with harmless blue dye (left) to allow for further observations after banding and release. RTHU from Hilton Pond Center are marked with green dye.

You WILL find it, however, in The Birds of Costa Rica--just published last year (2007) by Garrigues & Dean (left). It seems this species--the Tricolored Munia, Lonchura malacca--is a popular cage bird from an Old World family (Estrildidae); these days it occurs rarely as a free-flying escape in Costa Rica. Garrigues and Dean report "a small population [of munias] was discovered near the sugar mill in La Guinea, east of Filadelphia," between Palo Verde and Liberia, and that the population is expanding. The munia we captured in the aloe field was apparently part of that expansion. Our savvy land guide, Ernesto Carman Jr., recognized the bird--even though he had never seen a Tricolored Munia in the wild in Costa Rica.

You WILL find it, however, in The Birds of Costa Rica--just published last year (2007) by Garrigues & Dean (left). It seems this species--the Tricolored Munia, Lonchura malacca--is a popular cage bird from an Old World family (Estrildidae); these days it occurs rarely as a free-flying escape in Costa Rica. Garrigues and Dean report "a small population [of munias] was discovered near the sugar mill in La Guinea, east of Filadelphia," between Palo Verde and Liberia, and that the population is expanding. The munia we captured in the aloe field was apparently part of that expansion. Our savvy land guide, Ernesto Carman Jr., recognized the bird--even though he had never seen a Tricolored Munia in the wild in Costa Rica.

Oct 15 to Mar 15:

Oct 15 to Mar 15: