|

|

|||

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

|

|

INSECTS THAT STING:

What could be worse for an educator-naturalist than to be hypersensitive to insect stings and Poison Ivy? That, we're afraid, is our problem. If we merely pass by an ivy vine it reaches out and grabs us with adventitious roots and smears our skin with toxin--resulting in rashes and blisters that challenge our dermatologist. (And you can just imagine what happens in autumn if we pedal a bike through clouds of smoke from burning leaf piles that happen to include a few Poison Ivy leaflets.)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Because of our sensitivity, Poison Ivy--AKA Toxicodendron radicans (formerly Rhus toxicodendron or R. radicans) for its toxic foliage--is the only native plant we systematically eliminate from Hilton Pond Center. We feel a little guilty about this, knowing birds and small mammals eat ivy berries, but we rationalize our actions by saying we can't do much educating or naturalizing if our eyes are swollen shut and we itch so violently we can't concentrate on anything else. Even though our diligent ivy eradication work at the Center means we seldom get a rash anymore, we still keep handy a bottle of Technu medicated scrub--our favorite anti-ivy cure. We are most thankful Technu neutralizes and washes away urushiol, the oily compound in Poison Ivy and other sumacs that causes the rash.

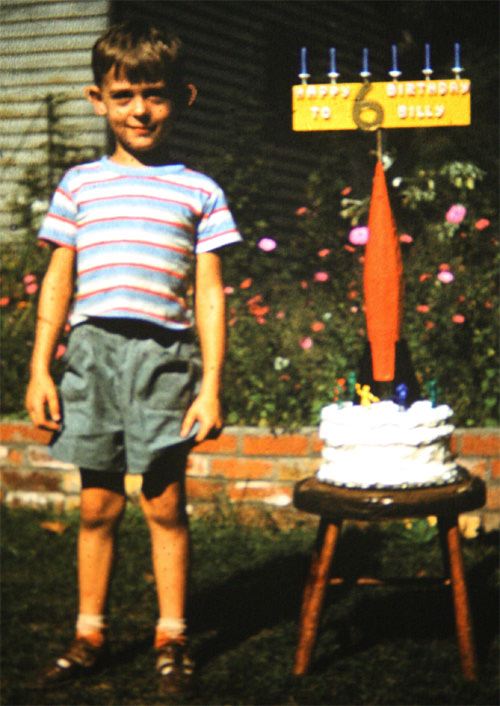

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Stinging insects such as Yellowjackets (Vespula germanica, above) are a whole 'nother matter, as we were reminded recently while strolling around Hilton Pond. 'Way back in the 1960s during undergraduate days at Newberry College, we were home for the summer living with parents in Rock Hill SC. This was the first time we'd been stung since the day before our sixth birthday--15 September 1952--which we stupidly celebrated by joining a same-age neighbor in throwing rocks at an underground nest of Yellowjackets. A photo (above right) taken at our "rocket ship-theme" birthday party shows of the aftermath: 24 welts on head, arms, legs, and torso; a puffy face; and two ears that looked like cauliflowers. That was a LOT of stings, and we learned very quickly and forevermore from this experience NOT to throw rocks at stinging insects.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center It was 14 years after the Yellowjacket rock-throwing incident that the Polistes wasp (above) zapped us just once during our college days, but one's body doesn't forget. We're guessing two dozen stings at age six sensitized our immune system because when stung again at age 20 our reaction included far more than swollen ears. Our ring finger began swelling immediately after the wasp sting--we luckily thought to take off our college ring before it was too late--and we soon broke out in itchy hives on legs and torso. Breathing became shallow and rapid and we got a massive histamine headache, but--most dangerously--our tongue began to swell and our windpipe started closing down. Fortunately, family patriarch Bill Hilton Sr. was in the yard and rushed his namesake to the local emergency room, where the doctor administered a shot of epinephrine before full anaphylactic shock set in and our windpipe closed completely. (A tracheotomy was imminent but, in the end, unnecessary.) Ever since we've been very careful around stinging insects and in the field usually carry an Ana-Kit; we've used it to give ourselves injections the two or three times we've been stung in the past 40 years and have never had any major problems--which brings us to our most recent encounter with insects that sting.

By strange coincidence, on the morning of 25 July 2009 we were preparing to depart Hilton Pond Center for an alumni mini-reunion for--you guessed it--Newberry College. Having just returned from a northern California trip (see our past two photo essays), we went out to check the trails and circumnavigate the pond for the first time in two weeks. As usual near the end of our walkabout we went onto a long pier (above) that reaches into Hilton Pond. There we scanned the open sky for birds and checked the moorings on a raft we keep at the end of the dock. One of the ropes had come loose, so we jumped onto the raft to secure it. As the raft stabilized we heard a buzzing noise and instantly felt as if we'd been jabbed and burned in several places with sharp needles. Wasp stings!

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Apparently, during our two-week absence a big colony of Polistes annularis Paper Wasps (above) had collaborated on building the mother of all nests beneath our floating raft. Not wanting to move quickly and further irritate these highly territorial insects, we sat down on the raft and slowly slid backwards toward the pier. This seemed to placate the wasps, albeit briefly, but then a second angry wave came toward us and stung some more. Without really thinking, we simply rolled off the raft into the water--fully clothed--and sank to the bottom. Since wasps were still swarming when we came up for air we went underwater again and made our way toward land. This time when we emerged the irritated insects were all back at the raft, so we stumbled onshore and shakily walked a hundred yards to our old farmhouse at Hilton Pond Center. There, we alarmed wife Susan with news of what had happened, went to the medicine cabinet, found an Ana-Kit, and injected some of that good old epinephrine into our thigh. Our leg immediately cramped and hurt worse than the stings. As recommended, we also took an oral dose of Benadryl--an antihistamine designed to counteract allergic response. After stripping off our wet clothes Susan was able to find at least 14 welts (below right), all of which were beginning to swell and redden. With so many stings we were in pain and feverish and a little disoriented, so we cancelled plans for the Newberry reunion and sat down to see how our body would respond.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center When we tell folks about our sensitivity to insect venom, some suggest we eliminate all wasps and bees and hornets around Hilton Pond Center through mechanical killing or spraying with insecticides. They argue this would be no different from our efforts to eradicate Poison Ivy from our property. Maybe we're exhibiting some sort of pro-animal bias,

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center So what's the deal with these stinging mechanisms? In the insect world, "true stingers" occur only among members of the Hymenoptera--four-membranous-winged insects such as bees, wasps, and ants--and then only in females. By definition, a "true stinger" is an internal abdominal structure the insect everts and sticks into its prey or potential predator while injecting venom. Spiders and centipedes deliver venom by biting, a scorpion pricks with the poison-laden tip of its abdomen, and certain poisonous caterpillars "urticate", i.e., scratch you with fine hairs laden with toxin--but unlike hymenopterans none of these creatures have stingers.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center True stingers are actually modified reproductive structures known as ovipositors. In non-stinging Hymenopterans, the female uses her ovipositor to make a hole through which she inserts an egg from the genital opening. However, among bees and wasps and ants that are often colonial the queen or fertile female(s) do not use their ovipositors in egg-laying. Within the colony the queen's work is supported by vast numbers of female workers that are generally sterile. It is these workers that create danger for folks allergic to insect venom, for when danger presents itself the insects' sharp ovipositors function not in egg-laying but in defense of the hive or nest. To make sure potential predators "get the point," ovipositor effect is enhanced by toxins from poison sacs at the stinger's base. In the case of a Yellowjacket we found and dissected this week, the stinger is pretty small--only about 1.5mm long and much enlarged in our 5X macrophoto above--but the attached poison sacs are capable of producing plenty of venom. Note the Yellowjacket's stinger isn't hollow like a hypodermic syringe but does have a lengthwise groove that likely allows more efficient flow of toxins from the poison sac. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center This week we also found a Bald-faced Hornet caught in one of the mist nets we use for bird banding. Unfortunately, the only way to extricate the hornet from the net was to kill it, but at least it died with its stinger everted (above). The hornet's ovipositor looks smaller in the photo than that of the Yellowjacket, but at 3.5mm is actually more than twice as long--which may be why a hornet sting feels like the kick of a mule.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Hornets do hurt but some ants are a greater problem for folks with insect allergies because ant workers bite AND sting. Although mandibles of really large ants can inflict painful pinches, the real function of the bite is to allow a worker ant to hold on while she stings--over and over and over again. Red Imported Fire Ants (above) are particularly adept at clamping down and re-stinging, which is one reason they're such dangerous pests where they've been introduced.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Among hymenopterans, not all individuals can sting multiple times. Terrestrial Yellowjackets and Bald-faced Hornets (an aerial species of Yellowjacket) are able to re-sting because, as our photos above reveal, their stingers are smooth--as is the case with ants. Conversely, the ovipositor of a Honey Bee worker is barbed; when she stings the stinger stays anchored in the predator. As the hapless Honey Bee pulls away, the stinger and poison sac both rip from her abdomen--a sort of "suicide mission" in which sac muscles continue to pump toxin even after the bee has died.

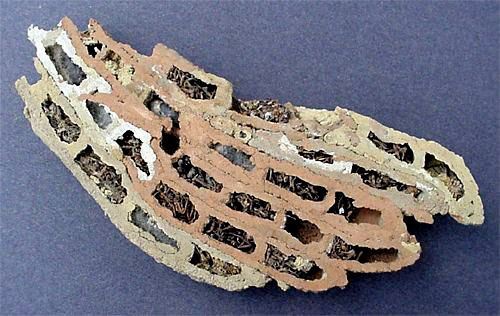

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center It's worth mentioning that hymenopterans don't always use their stingers in defense of a nest or hive. If you carefully watch mud dauber wasps, for example, you'll see they spend lots of time not just feeding on pollen and nectar or chasing predators, but also hovering beneath leaves. This usually means they're looking for a spider or caterpillar they sting just enough to immobilize before taking it back to the nest. There, they lay an egg on the limp but living prey and seal the victim into a nest compartment (note all the paralyzed spiders in our photo above of the Pipeorgan Mud Dauber's communal nest). Thus, when a wasp's larva hatches from the egg it has a ready source of fresh food to consume as it grows and prepares to pupate. Despite the "naturalist's dilemma" caused by our hypersensitivity to insect stings, we find hymenopterans to be fascinating organisms and try to protect our bees and wasps and ants from harm. If Honey Bees descend on our hummingbird feeders (below right), we hang them in the shade where they devices are less noticeable to bees. When Yellowjackets start coming for sugar water we change out the mix because these insects are more attracted by the smell and taste of fermenting sugar. (They spend much of their time eating animal matter--usually larvae and small insects that may damage economically important plants.) All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center POSTSCRIPT: It took almost a week to get over the direct effects of our late July wasp stings, and it appears the trauma compromised our immune system. By the ten-day mark we had contracted a double-whammy respiratory infection--part bacterial and part viral--that took us down for another couple of weeks. (The good news was we got a negative diagnosis for Swine Flu.) We mention all this as explanation for why we wrote so few installments of "This Week at Hilton Pond" in August and why those we did produce were tardy. (And we don't even want to talk about our recent near-death experience when the otherwise dependable 1998 Ford Club Wagon van we were driving lost its brakes on a steep descent down the mountain stretch of I-40 from Asheville NC into Tennessee, requiring a six-day weekend layover for extensive repairs.) All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

Comments or questions about this week's installment?

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond." (Please see Support if you'd like to make a gift of your own. You can also contribute by ordering an Operation RubyThroat T-shirt.)

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written & photographed You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use our on-line Hilton Pond Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to |

|

Make direct donations on-line via

Network for Good: |

|

|

Use your PayPal account

to make direct donations: |

|

|

If you like to shop on-line, you please become a member of iGive, through which more than 750 on-line stores from Barnes & Noble to Lands' End will donate a percentage of your purchase price in support of Hilton Pond Center and Operation RubyThroat. For every new member who signs up and makes an on-line purchase iGive will donate an ADDITIONAL $5 to the Center. Please sign up by going to the iGive Web site; more than 200 members have signed up to help. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. |

|

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS WEEK: * = New species for 2009 WEEKLY BANDING TOTAL 12 species 118 individuals YEARLY BANDING TOTAL (2009) 39 species 1,259 individuals 28-YEAR BANDING GRAND TOTAL (since 28 June 1982, during which time 170 species have been observed on or over the property) 124 species 52,141 individuals NOTABLE RECAPTURES THIS WEEK (with original banding date, sex, and current age) Ruby-throated Hummingbird (4) American Goldfinch (5) Northern Cardinal (1) Carolina Wren (1)

|

OTHER NATURE NOTES OF INTEREST

--In addition to a potful of young Northern Cardinals, a glut of recently fledged House Finches descended on the Center during the three-week period, many of them with one or both eyes affected by conjunctivitis (above). We suspect they get this highly contagious disease from their parents at the nest; if they survive infection, young birds apparently develop lifelong immunity but might still act as vectors. --Bill Hilton Jr. is honored to have been profiled as an outstanding alumnus in the Spring 2009 issue of Bio--magazine of the University of Minnesota's College of Biological Sciences, which awarded him a masters degree in Ecology & Behavioral Biology in 1982.

|

|

|

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) Up to Top of Page Back to This Week at Hilton Pond Center Current Weather Conditions at Hilton Pond Center |

You can also post questions for The Piedmont Naturalist |

Join the |

Search Engine for |

|

|

Arizona DSL Internet

Trying to be helpful around the house, we were getting ready one afternoon to water the garden with hose and sprinkler. As we reached for the outside water faucet, we felt a sharp burning sensation on our right ring finger. Wasp sting!

Trying to be helpful around the house, we were getting ready one afternoon to water the garden with hose and sprinkler. As we reached for the outside water faucet, we felt a sharp burning sensation on our right ring finger. Wasp sting!

We got a few hives but happily had no breathing problems; thanks to the Benadryl we semi-dozed off under Susan's watchful eye. Although we soon developed our inevitable histamine headache, it wasn't severe and everything else seemed relatively okay. Of course, for the next several days we felt like we'd been hit by a small truck--14 simultaneous wasp stings is significant trauma to one's body--but we gradually improved in time for our annual visit to the HummingbirdFest at Land Between the Lakes in western Kentucky, where we took it kind of easy during our three days of hummingbird banding demonstrations. We're amazed we didn't have major problems from our latest encounter with wasps; perhaps our immune system has become more tolerant through the years, or maybe we hadn't yet become sensitized to the particular type of venom in the latest wasp stings. Regardless, we're not about to test possible tolerance by subjecting the ol' bod to any more stings any time soon.

We got a few hives but happily had no breathing problems; thanks to the Benadryl we semi-dozed off under Susan's watchful eye. Although we soon developed our inevitable histamine headache, it wasn't severe and everything else seemed relatively okay. Of course, for the next several days we felt like we'd been hit by a small truck--14 simultaneous wasp stings is significant trauma to one's body--but we gradually improved in time for our annual visit to the HummingbirdFest at Land Between the Lakes in western Kentucky, where we took it kind of easy during our three days of hummingbird banding demonstrations. We're amazed we didn't have major problems from our latest encounter with wasps; perhaps our immune system has become more tolerant through the years, or maybe we hadn't yet become sensitized to the particular type of venom in the latest wasp stings. Regardless, we're not about to test possible tolerance by subjecting the ol' bod to any more stings any time soon.

but we always respond by saying the birds and small mammals can probably get along without Poison Ivy and its berries, while lots of flora and fauna depend on wasps and bees and hornets--particularly as pollinators (Polistes metricus Paper Wasp, on Goldenrod, above). As members of the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign (NAPPC), we like to remind folks at least one-third of all the food you eat today comes courtesy of pollinators, some of which like the female Carpenter Bee, Xylocopa virginica (on Swamp Milkweed, below), just happen to have stingers.

but we always respond by saying the birds and small mammals can probably get along without Poison Ivy and its berries, while lots of flora and fauna depend on wasps and bees and hornets--particularly as pollinators (Polistes metricus Paper Wasp, on Goldenrod, above). As members of the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign (NAPPC), we like to remind folks at least one-third of all the food you eat today comes courtesy of pollinators, some of which like the female Carpenter Bee, Xylocopa virginica (on Swamp Milkweed, below), just happen to have stingers.

And if communal wasps build a nest too close for comfort, we do knock it down in the dead of night when insects are sluggish, knowing they will go elsewhere and try again; however, we don't spray the adults. We draw the line at hosting Red Imported Fire Ants and lace their nests with specific baits to prevent the queen from laying, but otherwise do all we can to promote and protect stinging insects at Hilton Pond Center. When we consider the many important roles these native organisms play in the natural world, it's ALMOST worth getting stung every few years--just as long as our allergy kit is close at hand. After all, if we DON'T kill bees and wasps and ants we'd at least like them to return the favor.

And if communal wasps build a nest too close for comfort, we do knock it down in the dead of night when insects are sluggish, knowing they will go elsewhere and try again; however, we don't spray the adults. We draw the line at hosting Red Imported Fire Ants and lace their nests with specific baits to prevent the queen from laying, but otherwise do all we can to promote and protect stinging insects at Hilton Pond Center. When we consider the many important roles these native organisms play in the natural world, it's ALMOST worth getting stung every few years--just as long as our allergy kit is close at hand. After all, if we DON'T kill bees and wasps and ants we'd at least like them to return the favor.

Please report your

Please report your