|

|

|||

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

SPRINGTIME FERNS We know the more recent natural history of Hilton Pond Center--i.e., at least for the past three decades--because we've lived on site since 1982 and have first-hand observations about how natural succession has taken our 11 acres from grassland to forest. We can only speculate what this South Carolina land was like prior to European settlement--probably in about 1750 when the town of Yorkville (now York) was established--but we suspect it was similar to most of pre-history Carolina Piedmont: Oak-hickory forests growing from deep, rich topsoil; riparian bottomlands filled with birds and other wildlife; a plethora of wildflowers, shrubs, ferns, and mosses; and in some areas open spaces in the form of Piedmont prairies. Based on what we've been able to glean from conversations with local folks and from our own observations of such features as agricultural terraces and farming artifacts, what is now Hilton Pond Center had been in row crops or under graze for at least the past century--neither use being kind to the soil or local vegetation. Native flora that must have abounded pre-settlement are all but gone, so we're happy to see several ferns nearly absent just 28 years ago have begun to rebound under our laissez-faire policy of land management.

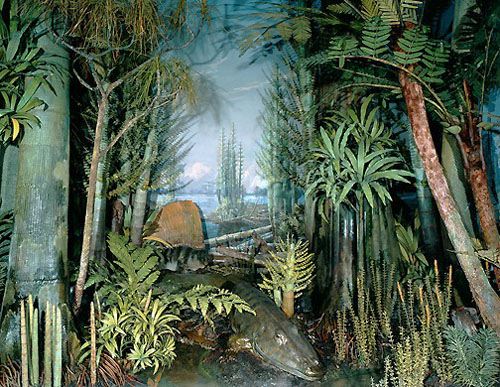

Image courtesy Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh It would be a shame to lose what ferns do grow at Hilton Pond Center if for no other reason than they represent an ancient plant lineage going back about 350 million years to the Carboniferous. Our fascination with that prehistoric era began during childhood days in Pittsburgh, where on much-anticipated visits to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History we stood transfixed at dioramas of the ancient coal forests (above)--complete with towering tree ferns, six-foot-long amphibians, and dragonflies with 24-inch wingspans. It was fascinating to learn how all these plants (and animals) lived and then died, eventually to be transformed into thick layers of coal underlying modern-day Pennsylvania. We don't have extensive underground coal beneath South Carolina--nor giant salamanders sliding about in Hilton Pond--but we do host a few modern-day representatives of those ancient ferns.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our biggest fern at the Center is a relative newcomer that first appeared about ten years ago on the downstream side of the dam that forms Hilton Pond itself. The species is Christmas Fern, Polystichum acrostichoides (above), which takes its common name from being evergreen and usable as a decoration during the holiday season. Each Christmas Fern frond is a single leaf subdivided into many leaflets attached to a central stipe; such compound leaves are common among ferns. One way to identify Christmas Fern is to examine larger leaflets (above left) at the bottom half of the frond; each has a thumb-like projection that makes the leaflet look like a cold-weather mitten; some folks say the "thumb" is actually Santa Claus in his sleigh--a second obvious tie to Christmas. (Because the leaflets are horizontal they can't be stockings; if they were, all the Christmas goodies would fall out!) All ferns propagate by spores, but how these reproductive units are produced varies widely. Some species have two types of fronds: Sterile ones that carry out photosynthesis, and fertile fronds that bear some sort of structure from which spores are released. In Christmas Fern, however, the base of a mature frond (above left) is the vegetative portion, while smaller leaflets nearer the tip have sori on their undersides.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center "Sorus" (pl. sori) is a generic term for a cluster of sporangia--spore producing structures--found in ferns, algae, and fungi. In Christmas Fern, each developing sorus on the leaflet's underside is protected by an umbrella-like indusium (above) that pops open as spores grow. Immature spores are first white and then yellow; when finally ripen they turn brown and are released from the sori if the frond is jostled by wind, raindrops, or passers-by.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center By far our most common fern around the Center is Ebony Spleenwort, Asplenium platyneuron (above), whose graceful 6-15" vertical fronds appear in disturbed, mostly dry microhabitats. This species superficially resembles Christmas Fern--even having a less-developed thumb on some of its larger leaflets--but the two are easily separated by other characteristics. Ebony Spleenwort takes its common name from its dark reddish-brown, almost black, stipe--the petiole to which leaflets are attached--and from the spleen-shaped sori (below) that occur on the undersides of those leaflets.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Incidentally, the suffix "wort" in Ebony Spleenwort comes from an Old English word meaning "plant." Historically, according to the "doctrine of signatures," a plant part that resembled a human body structure could be used to treat ailments of that structure.

When spores germinate they form a small, inconspicuous, short-lived prothallus; this structure, in turn, gives rise to male and female gametes that, through fertilization, produce a sporophyte that becomes the mature fern. This process, called "alternation of generations," is all-important to ferns but is the bane of high school biology students used to thinking of "more conventional" reproductive life cycles.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center About eight years ago a fern with coarsely dissected fronds (above) appeared in the only poorly accessible part of our property--a muddy, overgrown, swampy area at the base of the dam that forms Hilton Pond itself. Last winter, however, we finally donned hip boots and waded in for a more intimate view of the thriving fern patch that by now covers about 40 square feet. We were more than a little surprised to see the fern's few fertile fronds weren't at all similar to those of Sensitive Fern but were just like the much-less-common Netted Chain-fern, Woodwardia areolata. The vegetative foliage of these two species is indeed quite similar (especially from a distance), but fertile fronds of Sensitive Fern--AKA "Beaded Fern"--produce little bead-like structures, while Netted Chain-Fern's spores are contained in linear sori (above right, about 1.5X life size) that sort of resemble links in a chain. (To us they look more like sausage links.)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The sterile vegetative fronds of Netted Chain-Fern (above) are heavily lobed and, technically, aren't truly compound because there are no completely separated leaflets attached to the stipe by tiny stems. Even so, by being lobed and NOT casting a full shadow--the chain-fern's leaf allows all-important sunlight to filter down onto leaves growing closer to the ground.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our last two fern species at Hilton Pond Center are quite similar, having a single frond divided into three major leaflets that are more or less subdivided further. Rattlesnake Fern, Botrychium virginianum (above and below)--AKA Virginia Grape Fern--actually has leaflets with a very lacy appearance, while Common Grape Fern, B. dissectum, has leaflets that are somewhat coarser. (The latter is less common locally and we weren't able to find a specimen this week; thus, it's not included in this spring round-up of Hilton Pond Center's ferns. We might add that grape fern taxonomy is in dispute, with some botanists believing several current species should be lumped. Some authorities even use different generic epithets for some grape ferns, e.g., Botrypus virginianus and Sceptridium dissectum. Even more amazing, some think Rattlesnake Fern chromosomes may contain DNA fragments from a species of mistletoe!)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center In the various Botrychium species, reproduction is via a specialized second frond that arises from the apex of the main vegetative leaflets. Spores are borne in tiny spherical structures that supposedly resemble rattles on a snake's tail, hence the common name. (Spores were already gone from the fertile frond on the Rattlesnake Fern pictured above, Grape ferns are difficult to cultivate, apparently because a mycorrhizal soil fungus is a required symbiote in its rootstock. Thus, transplanted grape ferns almost always become increasingly smaller and die within three years. Because new grape ferns at the Center are sprouting a few yards away from established colonies, they likely are propagating by spores that have found the fungus; at the same time, rootstocks of established colonies are putting up additional vegetative fronds that make the colonies more dense. After perhaps a hundred years of agriculture followed by three decades of natural vegetative succession, ferns are finally making a comeback on our 11-acre sanctuary. Even though we only have five kinds of ferns in 2010, we're hopeful over time that wind and water--and maybe even birds and small mammals--will import spores and propagate new species of these ancient plants at Hilton Pond Center. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center POSTSCRIPT: Another ancient plant group--albeit not quite as old as ferns--is the mosses; they go back a mere 300 million years to the Permian Era. Although folks often lump "mosses and ferns" when they talk about non-flowering plants, the two groups aren't even closely related. Ferns are vascular--with special tissues called xylem (carries water) and phloem (transports food)--while mosses lack these two tissues.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Without vascular structures to move food, water, and nutrients to distant plant parts, "lowly" mosses can never grow tall and are relegated to clinging to rocks, tree trunks, and other stationary objects. Nonetheless, some mosses (above) superficially resemble ferns and are generically referred to as "fern mosses." (If you know the species for the above moss found at Hilton Pond Center, please contact RESEARCH.)

|

Numerous new fronds sprouting from asymmetric fountain-like clumps can be up to three feet long in mature plants, although the several specimens now established on the property are no more than half that size. As new fronds form in spring, the older ones go completely prostrate, turn yellow, and die (above).

Numerous new fronds sprouting from asymmetric fountain-like clumps can be up to three feet long in mature plants, although the several specimens now established on the property are no more than half that size. As new fronds form in spring, the older ones go completely prostrate, turn yellow, and die (above).

As in Christmas Fern, the sori of Ebony Spleenwort form on the undersides of terminal leaflets. Within a few weeks these translucent white spores (left) will turn almost black. These will be much more visible as dark spots as summer progresses.

As in Christmas Fern, the sori of Ebony Spleenwort form on the undersides of terminal leaflets. Within a few weeks these translucent white spores (left) will turn almost black. These will be much more visible as dark spots as summer progresses.

We assumed all along this was Sensitive Fern, Onoclea sensibilis, a very common species that occurs throughout the eastern two-thirds of the U.S. and Canada.

We assumed all along this was Sensitive Fern, Onoclea sensibilis, a very common species that occurs throughout the eastern two-thirds of the U.S. and Canada.

so at left we include one of our archival photos of somewhat similar spore cases from a Common Grape Fern taken in autumn.)

so at left we include one of our archival photos of somewhat similar spore cases from a Common Grape Fern taken in autumn.)