|

|

|||

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

MOURNING DOVE: Scarcely a day goes by at Hilton Pond Center that we aren't out walking the 2.5 miles of trails winding around the 11-acre property. Sometimes, however, we just pull up a stool on the back deck overlooking the pond to listen and watch. One of the most prevalent natural sounds--especially in early evening--is a soft, sad, repetitive cooing that lets us know our local Mourning Doves are courting again. Court is something Mourning Doves apparently do quite well, not just in spring like resident and migrant songbirds but for most of the year. Indeed, this is one species that probably nests somewhere in the U.S. during every calendar month; in addition, many pairs double- or triple-brood. This may be why there are so many Mourning Doves and why some experts consider them to be the most common and widespread native bird in North America, with an estimated continental population of about 375 million individuals. This abundance is a good thing, because Mourning Doves are also the most hunted game bird, with nearly a million harvested annually in South Carolina alone. We don't shoot doves at Hilton Pond but we do have something in common with appreciative hunters: The opportunity for in-the-hand, up-close views of a Mourning Dove's external attributes--photos of which we're pleased to share with you below.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Many backyard birders believe Mourning Doves, Zenaida macroura, are sexually monomorphic, i.e., that males and females look alike. Actually, it's pretty easy to differentiate adult females from males--especially when the latter are sporting their finest breeding plumage. The male (above) has a powder blue crown and nape, a well-developed blue-black spot on the neck, a rosy breast, and a dazzling patch of iridescence an his side just at the bend of the wing.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center By comparison, the female Mourning Dove (above) has a brownish cap, the blue-black spot is small, iridescence is generally lacking, and the overall appearance is more drab. According to our in-hand measurements females are also somewhat smaller, by 5-10%.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Mourning Doves forage primarily on the ground (winter male, above) where they gobble huge quantities of weed seeds. It's interesting they ingest almost no animal matter--not even tiny insects they may encounter among the leaf litter. Here at Hilton Pond Center, our small 20-bird flock of Mourning Doves spends a lot of time beneath any of several sunflower seed feeders, pecking through chaff for tiny morsels left behind by Northern Cardinals and House Finches.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center A few of our doves have even learned to perch on the trays of giant-sized Droll Yankees feeders, but we can't imagine they're able to open sunflower seeds with their relatively weak bills (above). Like other members of the Pigeon Family (Columbidae), the Mourning Dove has a bill that is hard for the anterior two-thirds, but soft and flexible at the base. This allows doves to do something few birds can do: They can open just the tip of the bill and can suck up drinking water just like a horse. Nearly all other birds--parrots are one exception--must dip their bills into water, allow the lower mandible to fill, and tip their heads backward to allow water to flow down their gullets.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center It's obvious Mourning Doves are built for speed--one reason so many of them are able to escape predators and even the sharpest of shooters. When the ten primary feathers on the folded wing in the photo above are fully extended the wing is quite pointed, allowing the dove to slice through the air. Especially when a Mourning Dove is taking off, wind actually whistles across its wing--making a distinctive audible sound that allows a person to identify the species without ever seeing the bird. Also visible in the photo above are large alular feathers at the bend of the wing--these allow the dove to fly more slowly without stalling--and shorter secondary feathers that are closer to the body than the primaries.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center A Mourning Dove's speed is further enhanced by a long tail (underside view, above) that tapers to a point. Unlike many birds that have rectrices of more or less equal lengths that form a rounded rear appendage, the tail of a dove consists of feather pairs that are progressively shorter, with the outermost (dark) pair being longest. The shorter feathers, when flared, create the familiar white flash on the edges of a Mourning Dove's tail. The crissum (undertail coverts) in this species are tan colored and help streamline the birds overall shape.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The legs of a Mourning Dove are also different when compared to those of most feeder birds. The dove's legs are relatively short and they are bright pink (above), especially during breeding season. And whereas most birds have scaly toes and exposed lower legs that are quite hard, these areas on a Mourning Dove are soft and fleshy--perhaps one reason the species appears more susceptible to frostbite.

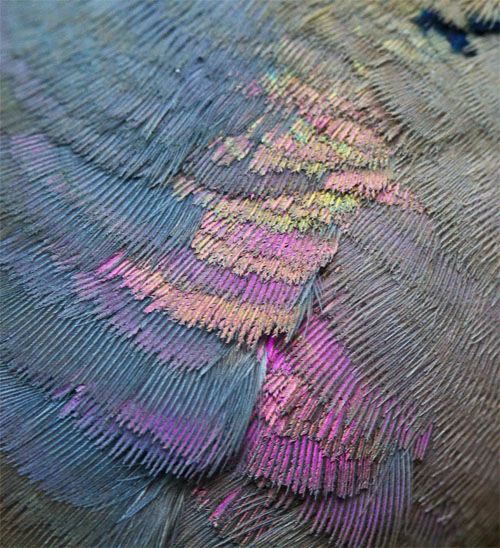

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center In close view we see the metallic patch on the shoulder of a mature male Mourning Dove (above) consist of overlapping feathers in various iridescent hues. As with other iridescence--such as the gorget of male Ruby-throated Hummingbird--this rainbow of pink and peach and lavender and gold is not caused by pigments; instead these are structural colors created when light is scattered by microscopic grooves and bubbles embedded in the feathers. In poor light the colors will appear much less intense and may even disappear from view.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The "wingpit" region of the Mourning Dove bears the species' only spotted feathers (above). Each of these is about 3" long and more or less symmetrical in shape, with a pronounced spot on one half. Although a dove's main wing feathers are typically stiff, quite strong, and resistant to wear along their entire length, the barbs at the bases of these spotted ones are quite soft and fluffy. Mourning Doves also have a profusion of down plumage that is similarly fluffy--plus unusual feathers known as "powder down" that flake off like dandruff and whose function is not well-understood. Yes, Mourning Doves may be the most common--and most commonly hunted--bird in North America, but for us they're still one of the more attractive avian species to be found at Hilton Pond Center. We do enjoy their mournful calls spring through fall, and on the wing or in-the-hand their fascinating external attributes are well worth admiring. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center  John James Audubon's rendering (above) of POSTSCRIPT: Here at Hilton Pond Center we've banded 436 Mourning Doves since 1982, making them our 20th most commonly captured species. Our most productive year was 2009, when we banded 44. In the previous 27 years we had just four of our banded Mourning Doves reported, so it was quite surprising last September when we got back-to-back-to-back notices that three more of our doves had been encountered--probably by hunters. When we finished exchanging information with the federal Bird Banding Lab we learned that was indeed the case. As shown on the table below, all seven of our banded Mourning Doves reported to the BBL were shot legally during a fall hunting season, and all were taken fairly close to Hilton Pond within our South Carolina home county of York.

Data from these seven Hilton Pond foreign encounters, combined with info collected by personnel from South Carolina's Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife service, provide wildlife biologists with better understanding of Mourning Dove ecology in the state--including survival, harvest rates, recruitment rates, and population trends that help determine bag limits and guide management decisions. Banding is the single most important tool in obtaining this information that would be unavailable otherwise. We appreciate Jake Peterson and Gray Culp of York and Jeff Holland of Early Branch SC for reporting doves we banded to the BBL at 1-800-327-BAND or on-line at BANDED BIRD REPORT FORM. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

|