|

|

|||

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

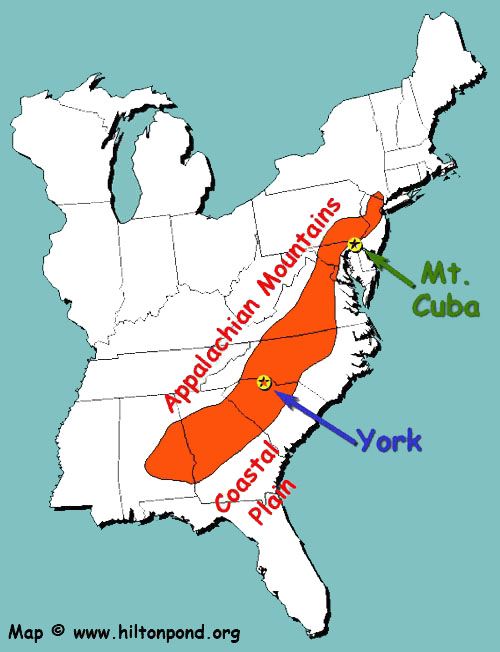

MT. CUBA CENTER: This week we jetted off from Charlotte NC to Baltimore-Washington International airport and then drove a little further north for a weekend at Mt. Cuba Center in Hockessin, Delaware. We became interested in Mt. Cuba shortly after 2001 when it was established as a non-profit nature center, primarily because its emphasis was "celebrating native plants of the Appalachian Piedmont." Not many facilities focus on ecology of the Piedmont Physiographic Province (see map below), so with Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History at the center of the Piedmont north-to-south and Mt. Cuba along the Delaware-Pennsylvania border near the Piedmont's northernmost limit, it seemed only appropriate the two organizations would eventually collaborate in some way. The first such endeavor was three days of "Hummingbird Mornings" presentations at which we got to share results of our North and Central American hummer research with teachers, citizen scientists, and general hummingbird enthusiasts.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center As a refresher, the Piedmont is that region of the eastern U.S. bounded on the west by the Appalachian Mountains and to the east by the Atlantic Coastal Plain. It stretches across ten states--all the way from southern New York to central Alabama--cutting large swaths through Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia. The Piedmont is 300 miles wide in North Carolina but covers only a few thousand acres in Delaware. The Piedmont is relatively low-altitude--between 200- and 1,000-foot elevation; Mt. Cuba is the second-highest "peak" in Delaware at about 300 feet.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Piedmont is characterized by a multitude of streams and rivers that sculpt the land into rolling hills (above) like those visible from Mt. Cuba's main building. Having been settled early by Europeans who divided it into farms and towns, the Piedmont is the most heavily fragmented region in the eastern U.S. Cattle grazing and row crops such as corn, cotton, and soybeans led to the demise of many forested areas and--to make matters worse--centuries of unwise cultivation practices allowed most of the region's topsoil to erode away, leaving vast expanses of telltale red clay visible at sites like Hilton Pond Center and beyond.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Mt. Cuba Center came into existence thanks to the generosity of Mrs. Lammot du Pont Copeland (nee Pamela Cunningham), whose will established a large endowment to underwrite operation of the 600-acre facility. Her vision was for a place where formal gardens and natural habitats could showcase native Piedmont plants including everything from towering oak trees to lowly mosses.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center The mansion's architectural touches are a wonder in themselves, especially the Conservatory (above) with painted fresco and glass skylights. When the Copeland family lived at Mt. Cuba, the Conservatory was filled with lilies at Easter, Poinsettias at Christmas, and a plethora of plant species at other times of the year. This required a staff of talented greenhouse and garden experts, some of whom still work at the Center.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Aside from Mt. Cuba's extensive trails and woodland pools, our single most favorite thing at the Center was Andre Harvey's breathtaking eight-foot-tall bronze sculpture of a samara (above). This anatomically correct rendering of a maple tree's winged fruit was cast and erected in 2009; it epitomizes Mt. Cuba's emphasis on native flora and, for us, emphasizes the strong link between art and nature.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center We went to Mt. Cuba Center this week at the invitation of its public programs manager, Eileen Boyle (above center), whose impressive professional pedigree includes stints as director of horticulture at New York Botanical Garden and the Philadelphia Zoo.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although hummingbirds were the focus of our lecture, workshop, and demonstrations at Mt. Cuba Center, we were enthralled with the lushly planted woodland trails that meandered around the estate and spent every non-instructional moment photographing as much Appalachian Piedmont flora as we could with our pocket-sized Canon G10. This didn't allow us the same flexibility as our big digital SLR Canon 7D with interchangeable lenses, but we still captured some images we'd like to share as the rest of this week's installment, starting with the one above of Cardinal Flower, Lobelia cardinalis.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Cardinal Flower is one of our Operation RubyThroat "Top Ten" native hummingbird plants, so we're always pleased to see it in the wild. At Mt. Cuba, it grows prolifically in formal settings but also thrives on edges and islands of several beautifully tended idyllic woodland pools (above). Although this crimson wildflower is a "perennial," most individual plants live only 5-10 years; fortunately, it propagates easily from seed and is pollinated most often by hummingbirds.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Closely related and similar in structure to Cardinal Flower is Great Blue Lobelia, L. siphilitica (above), whose species name indicates it was once thought to be a cure for venereal disease. (It is not.) This plant--like Cardinal Flower--is most at home in moist areas but adapts well to lots of situations. A rather short-lived perennial it, too, produces substantial nectar attractive to hummingbirds but is pollinated most often by Bumblebees.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another of our "Top Ten" native hummingbird plants--Indian Pink, Spigelia marilandica (above)--grows in profusion at Mt. Cuba Center, even though it is encountered less commonly in the wild. This tubular flower, a member of the Bellflower Family (Campanulaceae), is bright red on the outside with an unexpected contrasting pale yellow lining. There are reports this perennial is toxic, suppresses circulation and respiration, and causes muscular spasms, so we don't recommend it in a salad. The dark green foliage contains the alkaloid spigeline, which may be why deer seldom browse on Indian Pink.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although Green-and-Gold, Chrysogonum virginianum, looks like a five-parted flower, this species is actually in the Sunflower Family and grows across most of the Piedmont Region. As with other composites, what appear to be yellow petals are actually sterile ray flowers; the fertile disk flowers are at the center and each has its own complement of five tiny petals. At most locales this species flowers in spring AND again fall, taking off from blooming during the heat of summer.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center There are several kinds of plants collectively called "spiderworts"; the one above growing at Mt. Cuba is, we think, Common Spiderwort, Tradescantia virginiana, a native of the eastern U.S. and southern Canada. True spiderworts are in their own family, the Commelinaceae, and are unusual in that its blossoms are three-petalled (the majority of flowers have four petals or more), its blooms are decidedly ephemeral (often lasting less than 12 hours, hence the group's alternate name of "Dayflower Family"), and its inflorescence makes no nectar, attracting only pollinators that eat or collect pollen. Many folks are familiar with a non-native spiderwort with variegated leaves that is often grown in hanging baskets, i.e., T. zebrina, AKA Wandering Jew.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of the more unusual native wildflowers we found growing along the woodland trails at Mt. Cuba Center was the one above. A member of the Buttercup Family (Ranunculaceae)--it's probably Whiteleaf Leather-flower, Clematis glaucophylla. As with many Clematis, this plant produces a medusa-like seed head with long, more-or-less fuzzy appendages emanating from each individual seed. Ruby-throated Hummingbirds frequently visit this modified tubular flower. (If you wonder why we're a little hesitant on a few specific names for plants we photographed, it's because Mt. Cuba's philosophy is to NOT mark every single plant with an identification tag, relying instead upon its expert docents to help trail walkers interpret their surroundings. Thus--like Hilton Pond Center--Mt. Cuba Center is open only by appointment. To complicate matters, some "native" plants in Mt. Cuba's collection actually came from far-off parts of the Piedmont at which we've had little field experience.)

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Not all of Mt. Cuba's Piedmont wildflowers were bearing blossoms during our late-August visit. Some, like Jack-in-the-Pulpit, Arisaema triphyllum, flower in early spring but take several months for their seeds to develop. The big, four-inch cluster above included Jack-in-the-Pulpit berries in various stages of ripening; the green ones still have quite a ways to go. Incidentally, any given Arisaema triphyllum plant is either male OR female, which is why we claim at least some of them should be known as "Jills-in-the-Pulpit."

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another plant in fruit was Blue Cohosh, Caulophyllum thalictroides (above), whose name obviously comes from quarter-inch berries that appear in late summer. Blue Cohosh, a native perennial, is in the Barberry Family (Berberidaceae) along with familiar imported ornamentals such as Nandina domestica (Heavenly Bamboo) and Mahonia japonica (Oregon Grape). This medicinal herb was widely used by Native Americans for menstrual problems and to induce labor. It is widely available as a dietary supplement but for obvious reasons should never be taken during early stages of pregnancy.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Some plants at Mt. Cuba weren't flower- or seed-bearing at all, including various mosses and such flora as Northern Maidenhair Fern, Adiantum pedatum (above). Maidenhair is a compound-leafed fern with dark purplish-brown petioles that give rise to circular fronds that take on the form of a flat fan. This is an inhabitant of rich, moist woodlands--often growing in alkaline soil dampened by seeps or waterfall spray. The common name comes from a folk belief that if a maiden touches the Maidenhair Fern and its leaflets do not wither, she was "still virtuous."

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Where native plants abound you're likely to find not only hummingbirds but lots of other critters that use vegetation in one way or another, and that's certainly the case at Mt. Cuba Center. We saw a bevy of butterflies during our stay--most of which were flying too fast or too far away for us to image adequately with our pocket camera--so slow-moving butterfly larvae were more our speed. As expected, the colorful Monarch caterpillar above was resting head-down in late afternoon sun on a native milkweed (Asclepias sp.) we couldn't identify because the ravenous larva had completely defoliated its host. This particular caterpillar was only about an inch-and-a-half long and was sharing its perch with a colony of sap-sucking yellow aphids (upper right).

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Several dragonfly species were also in attendance at Mt. Cuba, especially around the woodland ponds where standing water provided appropriate habitat in which to lay their eggs. The one above paused long enough on a grass seed head to allow us a few exposures that confirmed it was a male Blue Dasher, Pachydiplax longipennis (above); females are yellow-green overall. (This species is sometimes confused with the slightly larger Eastern Pondhawk, Erythemis simplicicollis.) It may seem a little selfish, but dragonflies are among our heroes in the insect world, if only because they eat mosquitoes that otherwise might suck our blood and make us itch.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center Not every planting at Mt. Cuba focuses on native species, so around the manor we weren't surprised to see several showy beds of rosy-red Petunias that originated in South America. Many animals aren't all that particular about whether a plant is native or exotic, as was the case with some that came to partake of copious Petunia nectar. Most obvious were energetic inch-long insects that looked for all the world like some sort of baby hummer but were, of course, one of several species of diurnal moths referred to as "hummingbird mimics." The predominant species was Hummingbird Clearwing, Hemaris thysbe (above), whose fast-beating transparent wings, green back, long black proboscis, flared abdominal tip, and ability to hover while feeding on flowers make it easy to understand why folks sometimes do confuse lepidopteran hummingbird mimics with hummingbirds. These little moths are 'way to small too be young hummers, however, especially when one realizes baby hummingbirds are unable to fly.

Insect and flora, woodland trails and formal gardens made Mt. Cuba Center in northern Delaware a great place to spend a weekend sharing some of our hummingbird experiences, and we hope to return in future years. Staff and visitors were friendly and appreciative, there were plenty of native Piedmont plants and hummers, and our visit provided a welcome opportunity to travel to and investigate the "upper end" of the Piedmont Physiographic Province that reaches south past York SC and Hilton Pond Center. All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center

|

During the past nine years a growing staff has strived to define the Center's mission, expanding it with a more ecological theme in which plant-animal interactions are emphasized--hence their interest in hummingbirds that serve as important pollinators for several Piedmont flowers. Aside from a dizzying variety of native plants, the showcase of Mt. Cuba Center is an expansive Colonial Revival manor house (above) built in 1935 (historical photo above right) and that now contains offices, meeting rooms, and other facilities. The manor lawn provided a pleasant locale for some of our outdoor presentations.

During the past nine years a growing staff has strived to define the Center's mission, expanding it with a more ecological theme in which plant-animal interactions are emphasized--hence their interest in hummingbirds that serve as important pollinators for several Piedmont flowers. Aside from a dizzying variety of native plants, the showcase of Mt. Cuba Center is an expansive Colonial Revival manor house (above) built in 1935 (historical photo above right) and that now contains offices, meeting rooms, and other facilities. The manor lawn provided a pleasant locale for some of our outdoor presentations.

Eileen also happens to be keenly interested in hummingbirds--an interest that comes naturally because nectar-eating hummers often hang out in gardens and pollinate plants. After our Friday night public lecture, Eileen contributed to an all-day educator workshop on Saturday, unveiling some interesting home video of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in action. (See Eileen's still photo of a RTHU feeding on Trumpet Honeysuckle, above right.) Eileen also joined Mt. Cuba's highly skilled and energetic docents in leading field trips along the trails--all in pursuit of hummers feeding on spectacular late summer blooms of native plants.

Eileen also happens to be keenly interested in hummingbirds--an interest that comes naturally because nectar-eating hummers often hang out in gardens and pollinate plants. After our Friday night public lecture, Eileen contributed to an all-day educator workshop on Saturday, unveiling some interesting home video of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in action. (See Eileen's still photo of a RTHU feeding on Trumpet Honeysuckle, above right.) Eileen also joined Mt. Cuba's highly skilled and energetic docents in leading field trips along the trails--all in pursuit of hummers feeding on spectacular late summer blooms of native plants.