|

|

|||

|

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

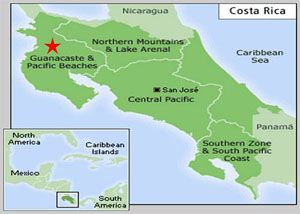

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center HUMMINGBIRD BANDING Each winter as we prepare to lead a new group of educators and citizen scientists on another hummingbird banding expedition to Costa Rica, we are already thinking about a trip report that will be our "This Week at Hilton Pond" photo essay when we return. With three such tropical trips already described on our Web site for Hilton Pond Center, we sometimes wonder if we'll produce enough new information and photos to give a fresh perspective on what we do in Guanacaste Province (below right). BEGINNINGS Our first tropical banding expedition occurred in late December 2004 at the behest of Holbrook Travel, whose representative--Debbie Sturdivant--recognized us at a science teachers convention the year previous and asked if we'd like to lead hummingbird trips to Costa Rica. Needless to say, Debbie didn't have to twist our arm very much. SUMMARY of the 2004-2005 EXPEDITIONS The first group we took to Costa Rica--known as the "Pioneers"--was met by potential failure when we arrived at Canas Dulces just after Christmas 2004, only to find the aloe was NOT in bloom. SUMMARY OF THE 2006 EXPEDITION Last year, we elected to visit our study site much later in the season, hoping the Aloe Vera would be in bloom by the end of the second week in February. CALENDAR CHANGE FOR 2007 To get a better handle on migration departure dates--and based on our results from last year--we backed up our just-completed 2007 excursion to the FIRST week in February, hopeful we could capture some of those elusive adult males before they departed Costa Rica on their northward journey. Knowing the aloe was in full bloom in late February 2006, we gambled such would also be the case in early February 2007. A PRE-TRIP DISAPPOINTMENT As noted in last week's installment (see Shade-grown Coffee), for 2007 we traveled to Costa Rica several days before our full group was scheduled to arrive. Flying into San Jose, we stayed with Ernesto at Finca Cristina, his parents' coffee farm at Paraiso. After a few days there, we rendezvoused with bus driver Alvaro and two Costa Rican teachers for a four-hour ride over the mountains to Guanacaste Province. As we neared Liberia on 2 February, we still had enough daylight to scout our 2006 study site, so we asked the driver to detour past the famed 2004-05 Jocote tree, across a rickety wooden bridge, and down a dusty half-mile road to the Aloe Vera plantation. We were NOT happy with what we saw next: The aloe field that practically had been teeming last year with ruby-throats was NOT in bloom! When we finishing our initial wailing, clothes-rendering, and teeth-gnashing, we scanned the big aloe plantation as far as we could see through binoculars; we noticed an adjoining field about 400 yards away looked like it had more blossoms, so we hurried off in that direction. Getting from the aloe stands at Canas Dulces to our home base at Buena Vista Lodge requires a 40-minute bus ride halfway up a volcano; it's not that far, but steep hills and valleys that make for slow going. (On the way up we stopped briefly at the village of Canas Dulces, where we were delighted to be recognized by Joey--a local boy who "helped us catch hummingbirds" back in the winter of 2004 when he was five, above right, but whom we had not seen in two years.) Eventually, we arrived at Buena Vista in time for supper, after which we unpacked and bedded down in anticipation of a trip back down the mountain the next day to meet the rest of our participants at the international airport in Liberia. THE ARRIVAL Liberia's airport is an interesting place. The facility is undergoing an expansion but much is still old-fashioned; passengers board and exit via rolling stairs rather than plane-level tunnels, and the waiting area for outgoing flights is a huge open-air hangar. Although Costa Rica has been a popular destination for many years, until fairly recently most ecotourists flew into the modern airport at San Jose and spent time in cloud forests on the Caribbean side of the country. These days, however, parts of the Pacific side are undergoing a development boom, with high-rise hotels, condos, and gated communities springing up like tropical weeds. Fortunately for inland wildlife--Ruby-throated Hummingbirds included--Guanacaste development is limited primarily to a narrow swath of coastal beaches, which is why many travelers who disembark at Liberia carry surfboards instead of binoculars and field guides.

Major airlines fly into Liberia daily, so there's more hustle and bustle than might be expected--especially on weekends. This year, as always, our arriving participants got their baggage, navigated customs and immigration, and assembled with no problem--thanks in part to our recognizable and highly coveted-but-still-available Operation RubyThroat T-shirts and a Hilton Pond Center sign wielded by Ernesto (above). As group members arrived, Alvaro loaded luggage into his sleek and shiny tour bus. We had a pleasant time getting acquainted with everyone--and stopping to look at Turquoise-browed Motmots--on the ride up to Buena Vista Lodge.

THE "LUCKY SEVENS" For 2007 we welcomed nine intrepid travelers intent upon unlocking the secrets of ruby-throats on the wintering grounds. Taking their group nickname from the calendar year, the "Lucky Sevens" included U.S. representatives Marie Baumann (Arlington VA), Elisabeth Curtis & Betsey Granda (Carrboro NC), Jeanine & George Kahrs (Victoria MS), Catherine & Nelson Latona (Fairfax VA), and Nancy Odom (Spartanburg SC), and our first-ever Canadian, Peggy Duszynski (Okotoks, Alberta). Thanks to Holbrook Travel and Hilton Pond Center, we again were able to offer full scholarships to two in-country educators; our ticas (Costa Rican women) for 2007 were Xinia Alvarez Espinosa and Tatiana Jiminez Padilla, both high school computer science teachers who are coordinators for The GLOBE Program on their respective campuses.

2007 DAILY ACTIVITIES After arrival day, our typical schedule was fairly constant. Ernesto, our living alarm clock, wakened everyone at 5:30 a.m. in time for a filling breakfast at 6 a.m.; most days it was fresh fruit and juice, sausage, scrambled eggs, and traditional Costa Rican black beans and rice. We were on the bus and on the way back down the volcano by 6:30 a.m. in time to arrive by 7 a.m. at the study site in Canas Dulces, where the crew worked quickly to deploy mist nets and set up the banding table. For about four hours or so we watched the nets closely, carefully unsnaring and then measuring and banding Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. (We occasionally caught non-RTHUs--including other hummingbirds such as the male Canivet's Emerald above; these were examined and released.) Our field workers were serenaded by sounds of the tropics--including the amazing vocalizations of Laughing Falcons two competing groups of Mantled Howler Monkeys. There was also plenty of time to take photos and record various observations about hummingbirds and habitats. Most afternoons group members were free to explore the Lodge's extensive landscape; folks often took a short siesta followed by day hikes, canopy tours, a dip in the pool, or a trip down a forest water slide or the zip-line (as demonstrated by an exuberant Catherine Wu-Latona at right). Every evening our entire group assembled at Mirador (below), a refreshment-laden lookout that faced west and allowed splendid views of the sun setting over distant peaks and the Pacific Ocean--a very peaceful ending to our daytime activities. Supper was always an ethnic buffet of fresh juice, fruits, and vegetables, various meats, black beans and rice, and a delectable dessert. After a short break, everyone gathered each evening for orientation and on-going lessons on observing and identifying hummers and collecting accurate data for the Operation RubyThroat/GLOBE hummingbird protocols.

2007 RESULTS For each of our eight-day Costa Rica hummingbird expeditions, the first and last days by necessity were used up by airport arrivals and departures; one full day has been devoted to visiting the dry topical forest at Santa Rosa, and another to the horseback ride to the spa. Since this left only four days for actual hummingbird observations, for 2007 we altered the schedule slightly to allow five mornings in the field.

The first banding day in 2007 was 4 February, when we introduced the Lucky Sevens to the aloe fields. This year's group was disappointed to see last year's primary site was essentially devoid of flowers, but remained positive as we "discovered" the nearby location our scouting team had found two days previously. The new study site was level ground of perhaps 20 acres of aloe, with slopes on the east and west sides that descended at 30-degree angles to adjoining streams. Although some flowers were present in the flat field, the majority of aloe blooms were on the slopes, so we decided to place our mist nets along the ridge at the top of each one--a task made easier because a dirt access road ran along each ridge. All mist nets (from Avinet) were 2.5 meters tall, made of 25-millimeter mesh (diagonal stretch), and with four shelves. On the west ridge we deployed four 12-meter-long nets with one 6-meter net running perpendicular down the slope (above); the east ridge got one 18-meter net along the road and one 12-meter net that ran perpendicular into the level field (below). After deployment we sat back each morning to wait for the first capture.

On Day One (4 Feb)--nine days ahead of the start day in 2006--we were in an instructional mode and took a little longer to get the nets out. We caught our first Ruby-throated Hummingbirds 8:35 and 8:38 a.m., about an hour and a quarter later than our earliest captures last year. What was really different about this year's first two birds, however, was that both were "adult" males with full red gorgets--something we never saw in our nets in 2006. As the morning progressed we caught three MORE red-throated males, an obvious second-year "juvenile" male (just four red feathers in a gorget that otherwise was white), and three white-throated females. This gave us a total of nine RTHUs--not a bad Day One for the Lucky Sevens.

Day Two (5 Feb) the group was more accomplished at setting the nets and we caught our first bird at 7:41 a.m.--a female that was followed by seven more like her. No males, adult or otherwise. After taking off 6 Feb for an extended field trip to Santa Rosa park and the Pacific Ocean, we were back in the Aloe Vera plantation on 7 Feb (Day Three), when we again caught eight birds: six females, one adult male, and one second-year male with five red throat feathers. Day Four (8 Feb) was EXTREMELY slow; we caught only ONE bird--a female. Day Five (9 Feb)--our last one among the Aloe Vera--was also slaw-going, with only four females banded.

In all, five days in the field this year netted 30 birds--twice as many as our two excursions in the winter of 2004-2005, but just 60% of the 2006 total of 51 (see table above). Remarkably, however, we captured six adult males in 2007--after banding none in 2006. By Days Four and Five this year some hummers obviously had become familiar with the nets and made sudden directional changes to zip over them without getting caught, but we also SAW very few hummers on the last two days in the field. This relative absence of RTHUs at the end of the week--plus the fact we caught five adult males on Day One and only one more on Day Three--leads us to suspect hummingbirds may move through Guanacaste's Aloe Vera fields in waves as migration begins. We may have gotten there just in time this year to catch the "last wave" of adult males. Based on our 2006 work, it looks like ALMOST ALL adult males are gone from Guanacaste by the third week in February; this year's results suggest MANY are gone two weeks before that. One way to check this hypothesis is to be in Costa Rica NEXT year by the last week in January to see if greater numbers of adult males are still present; that will be our plan, with the first trip in 2008 tentatively scheduled to begin on 25 Jan. (PARENTHETICAL NOTE: At Hilton Pond Center, adult females outnumber adult males 3:2, so it's possible a similar imbalance exists on the wintering grounds at Guanacaste. However, the 2007 ratio was 22 females to six adult males, which would be a heavily skewed 11:3 ratio. It's also possible adult males are present in Guanacaste but using different food resources than aloe; they also may overwinter at some other location.)

THE CLIMAX OF 2007 We hope you've stuck with us this far in our narrative for 2007 because we've saved the best for last. On our final day of field work (9 Feb), we were sitting at the banding table shortly after 10 a.m., working with a new female Ruby-throated Hummingbird we had netted at 9:54 a.m. We then turned to the bird Ernesto had just brought, removed it from the lingerie bag, and were delighted to see it was an apparent adult male (above right)--albeit in very heavy throat molt with many gorget feathers still in quill. Following our usual protocol, we slid the hummer into an open-ended paper tube (below left) that we then placed on a portable digital scale used to weigh each bird. (The tube is a very safe way to hold a hummer, since it keeps the bird from struggling or hurting itself. Besides, we've never been able to get a ruby-throat to perch on a scale while we determined its weight!) Typically, after weighing we then slide the bird out of the tube just far enough to expose its legs, using modified needle-nosed pliers to apply the band. As we asked our scribe to be sure she had recorded the weight of Ernesto's new bird, Most bird bands have two sequences of numbers, a four-digit prefix number and a five-digit specific number. Hummer bands are far too small for that much information, so they bear just a prefix letter and five numerals. "C51597 is the next one in the series?" we asked the scribe, who verified that was indeed the correct band. Then we opened the band slightly--making a gap big enough to allow it to slide around the hummer's tiny leg--and placed it in the tip of the pliers we would use to crimp it down gently to close the gap. Next we gently grabbed the toes on the hummer's left foot to stabilize it, slid the pliers and band into position--and suddenly froze. And stopped breathing. And looked directly at Ernesto, who was still shaking, and sweating, and smiling a very large smile. There was no way we could band this particular male Ruby-throated Hummingbird because (as Ernesto discovered while removing it from the net) . . . this bird was already banded! When we uttered the phrase "This bird is already banded," every member of the Lucky Sevens field crew stopped dead in his or her tracks, pivoted in place, and walked quickly to the banding table. Having spent many long, hours in the Aloe Vera fields, every one of these hummingbird enthusiasts from North America KNEW "this bird is already banded" could be the most important words uttered by anyone all week, and they, too, became breathless. Slowly, we extended the hummer's legs just enough to see the band clearly, and reminded the Lucky Sevens of a few band number facts. "During the first winter of work here in Costa Rica," we reiterated, "we banded 15 RTHUs, so the bands we used that year were C51501 through C51515. In 2006 we caught 51 more, using C51516 through C51566. This year we've banded 30 birds, so our 2007 sequence is C51567 through C51596. Back at Hilton Pond we've used various prefix letters, currently the letter 'Y' and previously 'X' and 'T.' Other banders elsewhere may have bands with some other prefix letter." The excitement and tension began to mount as we turned the band slightly on the ruby-throat's leg to get a better look and began to read. "C" was the first thing that came into view, meaning this was possibly one of our birds from Guanacaste.

As we rolled the band 'twixt thumb and forefinger, we then could read the first numeral--a "5" (above)--and then a "1" and another "5" that guaranteed this was one of our Guanacaste hummers. The next two digits would be the most important, and a shout went up from the Lucky Sevens when we finished the sequence with "1" and "7." This little bird was C51517, whose records show he was the second bird the "Oh-Sixers" caught on their first day of banding back in 2006. So why the excitement about this particular Ruby-throated Hummingbird? For one, when we banded it on 13 February 2006 in the adjoining Aloe Vera field, it was already an "adult" after-hatch-year male with a full red gorget. That meant this year it was an after-second-year bird that had to have hatched out no more recently than the summer of 2005--on RTHU breeding grounds in North America; it was in at least its third year of existence. But of much greater importance was the fact that this bird from North America had flown to Guanacaste in the winter of 2005-2006, almost certainly returned to its breeding grounds in the U.S. or Canada last summer (there are no "summer" records for RTHUs in Costa Rica), and then came back to Guanacaste again of the winter of 2006-2007.

So what's the big deal about that? Everybody already knows ruby-throats migrate back and for between Central and North America and based, for example, on our work at Hilton Pond Center, some hummers return to the same breeding locales for up to five years in a row. In other words, RTHU site fidelity at North American sites is well-documented. However, even though experts have suspected Ruby-throated Hummingbirds could show similar site fidelity on their wintering grounds, until we re-captured old C51517 (above) in a later year at Canas Dulces, Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica, no one knew for sure. It only takes one ruby-throat to show winter site fidelity apparently occurs in the Neotropics for this species, and C51517 has become that bird. What a great way to spend our last day in the field in Costa Rica--discovering something about hummingbirds that we believe is completely new to science. The Lucky Sevens were elated, and very cognizant of the accomplishment. Who knows, maybe next year we'll find the Hummingbird Holy Grail--the first-ever tropical recapture of a ruby-throat banded in North America or Canada. If that happens, you'd really want to be there, wouldn't you? If so, please take a look at the info about our upcoming 2008 Costa Rica Hummingbird Banding Expeditions and register early while there's still room. We can't guarantee we'll catch that Hummingbird Holy Grail next year, but we will promise you'll have an enjoyable, unforgettable experience mimicking the migratory path of the Ruby-throated Hummingbird and helping study these little balls of fluff on their tropical wintering grounds.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center POSTSCRIPT: Although we take a serious and scientific approach to hummingbirds, we felt obligated to mention a factor that may have had an impact on this year's recapture of C51517. After completing field work on 8 Feb we took the Lucky Sevens on an outing to Liberia, where everyone gathered for lunch, toured the town, and bought souvenirs. GUANACASTE PHOTO GALLERY Although participants in our hummingbird banding excursions to Costa Rica work hard to help capture and observe Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, there's always lots of time to have fun and to explore the wonders of the countryside. We include the following photos as examples of the biological diversity of Guanacaste Province and of the variety of activities that occur during our annual expeditions to the tropics.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center This eight-inch-long Ruddy Woodcreeper, Dendrocincla homochroa, was immobile for a long while, hiding on the shady side of a tree trunk on the trail at Buena Vista Lodge. Woodcreepers, of which there are 15 species in Costa Rica, resemble but are not related to woodpeckers.

Next to Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, the most common trochilids in our Aloe Vera study site were Cinnamon Hummingbirds, Amazilia rutila (above) and Green-breasted Mangos, Anthracothorax prevostii. We also observed and/or netted Canivet's Emerald, Chlorostilbon canivetii, and Plain-capped Starthroats, Heliomaster constantii. Sexes appear the same in the Cinnamon.

Several other non-hummingbirds occasionally hit our 25-mm mesh mist nets; larger birds often bounced out, but some of the smaller ones--including this Common Ground Dove, Columbina passerina--managed to get snared. This little bird is about half the size of a Mourning Dove.

This nondescript greenish-yellow bird would probably fool lots of American birders in Costa Rica, even though they might recognize the species on its breeding grounds in coastal regions of the southeastern U.S. As a hint, the bird above is a female, and her male counterpart is among the most colorful of all North American birds. Her light eye ring and heavy conical beak are important field marks. (Give up? It's a Passerina ciris, also known as Painted Bunting.)

Anyone who doubts Aloe Vera is a rich source of nectar for hummingbirds need only dissect one of its tubular blossoms. This will reveal a large drop of energy-laden nectar inside the base of the flower tube--a fluid that, we discovered by tongue-testing, also tastes pretty good to humans.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The rich nectar load within Aloe Vera flowers is bound to attract organisms besides hummingbirds. In the photo above a tiny unidentified bee scarcely a quarter-inch long goes after some sweet juice, but does so in a way that thwarts the aloe's reproductive strategy. The bee chews its way through the tubular corolla rather than entering via the bottom opening where stamens and pistil would force the insect to become a pollinator.

And speaking of Aloe Vera, a member of our 2007 group--Marie Baumann of Arlington VA--created this watercolor study of the plant and its flowers while working in the aloe fields at Canas Dulces.

On the way to our study site each morning, we passed a small pond--a rare commodity in the relatively arid region of Guanacaste Province where we do our hummingbird work. Most days a tree overhanging the pond was adorned with white ornaments--a flock of two dozen or so Cattle Egrets, Bubulcus ibis, warming up in the early morning sun.

The route to the banding site also included a deep valley created by a still-active stream. At one point the tributary is bordered by an 80-foot sheer rock wall that is home to orchids, bromeliads, and wildflowers. A six-foot-tall swath near the stream's surface is moist enough to support lush grown of ferns, mosses, and liverworts (above)--plants that are much less common in Guanacaste than in the rain forests on the eastern side of Costa Rica.

The annual day trip to Santa Rosa National Park in northwestern Guanacaste is always a highlight of our stay in Costa Rica. Under the expert guidance of Ernesto Carman, participants get to experience one of the country's last remaining big stands of tropical DRY forest--an interesting ecosystem whose canopy trees can be either evergreen or deciduous. Here Ernesto points out a tubular red flower that is frequented by hummingbirds.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although Green Iguanas, Iguana iguana, do occur in Costa Rica, in Guanacaste you're far more likely to encounter a Ctenosaur--the Black Iguana, Ctenosaura similis. Recent hatchlings of this species are also green but acquire their dark coloring during their first year. These are heavy-bodied lizards that can reach four feet or more in length. The one above posed on the trail at Santa Rosa; note the two light-colored ticks in its ear canal.

On our day trip to Santa Rosa, we also drive to Junquillal Beach, a public swimming area within the national park. Since they are in a protected area, the beach and forest that surround the beach are great places to watch birds and other wildlife. Most of our Lucky Sevens group members went for a dip in the cool waters of the Pacific, alert nonetheless to such natural splendors as Magnificent Frigatebirds, Fregata magnificens (above) feeding in the cove. Among other seabirds were Common Terns, Sterna hirundo, and Brown Pelicans, Pelecanus occidentalis, and in the woods we watched a guild of White-throated Magpie-Jays, Calocitta formosa, feeding on fruits and nuts. Junquillal Beach is also well-known as an important sea turtle nesting ground.

One of our favorite spots at Junquillal Beach is a hollow tree near the main bathhouse. Each year we check to see if it's still home to a colony of unidentified stingless bees we discovered within its trunk back in 2004-2005, and we've never been disappointed. These bees built a filigreed tube of wax leading to a hive deep within the tree; during daylight hours a steady stream of bees enters and leaves the mouth of the tube. One bee is always positioned just outside the lip; we're not sure if she's an early warning system for intruders or whether she might have a little clicker to count the seemingly infinite number of bees that come and go.

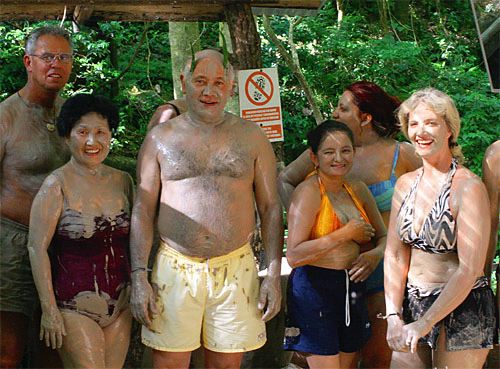

After the horseback ride, Buena Vista's volcanic spa is a welcome sight for our caballeros. However, there's no soaking in the soothing hot springs until everyone is slathered with hot volcanic mud that exfoliates the skin and hides in various crevices, only to be discovered days later after group members return home to the U.S. or Canada. This year, Nelson Latona (yellow trunks, above) was crowned King of the Spa and anointed with horn-like fronds of a secret plant that has unknown medicinal properties.

Each afternoon at Buena Vista Lodge, as the sun draws closer to the horizon, the Lucky Sevens and all their predecessors have gathered at Mirador Lookout to watch the shadows lengthen. Sugarloaf Mountain (in the middle distance) and the coastal ridge beyond never fail to delight us as every sunset is unique and different--a terrific way to end a long day of catching, banding, and observing Ruby-throated hummingbirds in Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Don't forget. We've already posted tentative dates and information about signing up for next year's trips at 2008 Costa Rica Hummingbird Banding Expeditions.

Comments or questions about this week's installment?

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond."

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written & photographed You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use our on-line Hilton Pond Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to |

It's an idle thought, however, because we never fail to have unique experiences to share with our Web site visitors, and we ALWAYS learn something new and exciting about Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (RTHUs) on their wintering grounds. Our 2007 trip on 3-10 February was no exception, and one thing we learned this year about RTHUs on our very last field day in Costa Rica was EXTREMELY exciting--a concept not new just to us but to science. But we're getting ahead of ourselves here, and we don't want to give away the surprise ending without first putting everything into context!

It's an idle thought, however, because we never fail to have unique experiences to share with our Web site visitors, and we ALWAYS learn something new and exciting about Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (RTHUs) on their wintering grounds. Our 2007 trip on 3-10 February was no exception, and one thing we learned this year about RTHUs on our very last field day in Costa Rica was EXTREMELY exciting--a concept not new just to us but to science. But we're getting ahead of ourselves here, and we don't want to give away the surprise ending without first putting everything into context! We eventually recruited two groups of participants through Hilton Pond Center and Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project; Holbrook took care of all travel, lodging, and logistical details--and linked us up with Ernesto Carman, a knowledgeable, bilingual nature guide who told us northern Guanacaste Province is THE place in Costa Rica to find wintering ruby-throats. Ernesto had observed good numbers of RTHUs feeding in Aloe Vera fields at Canas Dulces just north of Liberia and predicted we could capture and band the species there.

We eventually recruited two groups of participants through Hilton Pond Center and Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project; Holbrook took care of all travel, lodging, and logistical details--and linked us up with Ernesto Carman, a knowledgeable, bilingual nature guide who told us northern Guanacaste Province is THE place in Costa Rica to find wintering ruby-throats. Ernesto had observed good numbers of RTHUs feeding in Aloe Vera fields at Canas Dulces just north of Liberia and predicted we could capture and band the species there. Fortunately we discovered a single Jocote tree (below right) upon which hummers were feeding; using elaborate deployments of pull-string traps and mist nets we were able to band six RTHUs during our eight-day trip. The Pioneers were followed immediately by a "Second Wave" of volunteers who helped catch another nine, bringing the 16-day total to 15 RTHUs--a mix of females and second-year and "adult" males. This might not seem like very many hummingbirds, but it WAS the first time anyone had ever systematically banded, color marked, and observed RTHUs on tropical wintering sites. Among other things we learned at least some ruby-throats defend territories in Guanacaste just as aggressively as on the breeding grounds.

Fortunately we discovered a single Jocote tree (below right) upon which hummers were feeding; using elaborate deployments of pull-string traps and mist nets we were able to band six RTHUs during our eight-day trip. The Pioneers were followed immediately by a "Second Wave" of volunteers who helped catch another nine, bringing the 16-day total to 15 RTHUs--a mix of females and second-year and "adult" males. This might not seem like very many hummingbirds, but it WAS the first time anyone had ever systematically banded, color marked, and observed RTHUs on tropical wintering sites. Among other things we learned at least some ruby-throats defend territories in Guanacaste just as aggressively as on the breeding grounds.  Indeed, when the "Oh-Sixers" arrived at Canas Dulces on the 12th, we were elated to see a profusion of four-foot stalks of yellow aloe blossoms--many being visited by Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. During that 2006 expedition we more than tripled the previous year's totals by banding 51 RTHUs, but were surprised not a single one was an "adult" male with a full red throat. At most locations in the U.S. and Canada male ruby-throats arrive before females in spring, so we figured local "adult" males had already departed Costa Rica on their northward journey--although numerous second-year males with incomplete red gorgets were still present and feeding on aloe (above left).

Indeed, when the "Oh-Sixers" arrived at Canas Dulces on the 12th, we were elated to see a profusion of four-foot stalks of yellow aloe blossoms--many being visited by Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. During that 2006 expedition we more than tripled the previous year's totals by banding 51 RTHUs, but were surprised not a single one was an "adult" male with a full red throat. At most locations in the U.S. and Canada male ruby-throats arrive before females in spring, so we figured local "adult" males had already departed Costa Rica on their northward journey--although numerous second-year males with incomplete red gorgets were still present and feeding on aloe (above left). Fortunately our binocs had not misled us and we determined this new field--although not as profuse with blooms as last year's site--would have to serve as the locale for our banding operations for 2007.

Fortunately our binocs had not misled us and we determined this new field--although not as profuse with blooms as last year's site--would have to serve as the locale for our banding operations for 2007.

By 11:30 a.m. we were furling the nets and stowing everything for the return trip to Buena Vista Lodge, where a tasty buffet lunch of salad, meats, and the ubiquitous black beans and rice awaited us.

By 11:30 a.m. we were furling the nets and stowing everything for the return trip to Buena Vista Lodge, where a tasty buffet lunch of salad, meats, and the ubiquitous black beans and rice awaited us.

Over four weeks of work in three winters, we've now banded 96 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in Costa Rica. This is pretty interesting in itself, especially when we note this is the largest known assemblage of banded RTHUs anywhere south of the U.S. and Canada. Among other things, these birds are teaching us much about RTHU molt sequencing on the wintering grounds. In Dec 2004-Jan 2005, all ruby-throats we captured were had at least begun wing molt, with most showing NEW inner primary wing feathers 1-6 and OLD outer primaries 7-10 (above left).

Over four weeks of work in three winters, we've now banded 96 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in Costa Rica. This is pretty interesting in itself, especially when we note this is the largest known assemblage of banded RTHUs anywhere south of the U.S. and Canada. Among other things, these birds are teaching us much about RTHU molt sequencing on the wintering grounds. In Dec 2004-Jan 2005, all ruby-throats we captured were had at least begun wing molt, with most showing NEW inner primary wing feathers 1-6 and OLD outer primaries 7-10 (above left).  Last year (late February 2006), most had new primaries 1-8, an old 9, and a 10 "in quill" (right), but this year (early February 2007) the majority still had old 7-10 or 8-10 primaries. Obviously, Guanacaste RTHUs begin molting primary feathers sometime in December and probably finish up by late February. They hold the all-important #9 primary until last, which makes sure it--the heaviest of the wing feathers--is fresh and in optimal shape for northward migration. It's worth noting that one female RTHU we banded this year on 4 Feb was recaptured in a different net on 7 Feb; her #10 primary was missing at time of banding, but just four days later was more than half grown--indicating a very rapid growth rate.

Last year (late February 2006), most had new primaries 1-8, an old 9, and a 10 "in quill" (right), but this year (early February 2007) the majority still had old 7-10 or 8-10 primaries. Obviously, Guanacaste RTHUs begin molting primary feathers sometime in December and probably finish up by late February. They hold the all-important #9 primary until last, which makes sure it--the heaviest of the wing feathers--is fresh and in optimal shape for northward migration. It's worth noting that one female RTHU we banded this year on 4 Feb was recaptured in a different net on 7 Feb; her #10 primary was missing at time of banding, but just four days later was more than half grown--indicating a very rapid growth rate. We anticipated this would be our last bird of the year, for we needed to shut the nets a bit early at 10:30 a.m. to get back to Buena Vista Lodge in time for lunch and our afternoon horseback ride to the volcanic spa. As we weighed the hummer, our hardworking tico guide, Ernesto Carman, came to the table with a bird in one of the mesh lingerie bags into which we temporarily place RTHUs after removing them from mist nets. We were pleased to get one more hummer and told Ernesto so, but we also had to ask why his hands were shaking. Figuring Ernesto was just kidding around, we hung the bag in the shade behind the banding table and continued to record measurements for the female RTHU in hand.

We anticipated this would be our last bird of the year, for we needed to shut the nets a bit early at 10:30 a.m. to get back to Buena Vista Lodge in time for lunch and our afternoon horseback ride to the volcanic spa. As we weighed the hummer, our hardworking tico guide, Ernesto Carman, came to the table with a bird in one of the mesh lingerie bags into which we temporarily place RTHUs after removing them from mist nets. We were pleased to get one more hummer and told Ernesto so, but we also had to ask why his hands were shaking. Figuring Ernesto was just kidding around, we hung the bag in the shade behind the banding table and continued to record measurements for the female RTHU in hand.  When we finished with her, we offered her a drink of sugar water and color-marked her (above left) with the necklace of turquoise dye we apply to all RTHUs we band in Guanacaste.

When we finished with her, we offered her a drink of sugar water and color-marked her (above left) with the necklace of turquoise dye we apply to all RTHUs we band in Guanacaste. we also double-checked with her to make sure we were placing the band with the correct number on the new bird's leg.

we also double-checked with her to make sure we were placing the band with the correct number on the new bird's leg.

One woman commented she was glad this recapture happened on the final day because had it been Day One she might not have fully understood the significance of the recapture. But significant it was, and we thank the Lucky Sevens for signing up for the trip, for their and Ernesto's conscientious work in the Aloe Vera fields, and for their appreciation of the wonders of migration in Ruby-throated Hummingbirds.

One woman commented she was glad this recapture happened on the final day because had it been Day One she might not have fully understood the significance of the recapture. But significant it was, and we thank the Lucky Sevens for signing up for the trip, for their and Ernesto's conscientious work in the Aloe Vera fields, and for their appreciation of the wonders of migration in Ruby-throated Hummingbirds.

Catherie Wu-Latona purchased an inexpensive coconut shell carving depicting hummingbirds (left) and had it on at supper that evening. We commented that Catherine made a wise purchase and that everyone in the group should rub the necklace to see if it might improve our success next time we tried to capture ruby-throats. Catherine wore her pendant the next morning at the Aloe Vera study site, where our recapture of C51517 made him the first known example of a Ruby-throated Hummingbird returning to the same location on the wintering grounds. Was it simply coincidendal that Catherine wore the pendant AND that we caught C51517? We don't know for sure, but in honor of this significant recapture Catherine graciously awarded us the pendant for use in later years. We intend to wear it ANY time we're trying to catch hummingbirds, whether around Hilton Pond, in Guanacaste, or at some other locale. You never know . . . .

Catherie Wu-Latona purchased an inexpensive coconut shell carving depicting hummingbirds (left) and had it on at supper that evening. We commented that Catherine made a wise purchase and that everyone in the group should rub the necklace to see if it might improve our success next time we tried to capture ruby-throats. Catherine wore her pendant the next morning at the Aloe Vera study site, where our recapture of C51517 made him the first known example of a Ruby-throated Hummingbird returning to the same location on the wintering grounds. Was it simply coincidendal that Catherine wore the pendant AND that we caught C51517? We don't know for sure, but in honor of this significant recapture Catherine graciously awarded us the pendant for use in later years. We intend to wear it ANY time we're trying to catch hummingbirds, whether around Hilton Pond, in Guanacaste, or at some other locale. You never know . . . .

We've observed Mantled Howler Monkeys, Alouatta palliata, on each of our Costa Rica trips; in 2007 our hummingbird study site appeared to be on the border between the territories of two very active monkey groups. Each morning, as we netted and banded hummingbirds, we were serenaded by roaring calls of vociferous adult males--sometimes in trees less than 20 yards away from the banding table. (Male howlers are the loudest of all land animals except humans with boom boxes; females also make noise, but it's more like a low grunt.) Howlers are the only true folivores among the New World monkeys, eating canopy tree leaves along with buds, flowers, fruits, and nuts.

We've observed Mantled Howler Monkeys, Alouatta palliata, on each of our Costa Rica trips; in 2007 our hummingbird study site appeared to be on the border between the territories of two very active monkey groups. Each morning, as we netted and banded hummingbirds, we were serenaded by roaring calls of vociferous adult males--sometimes in trees less than 20 yards away from the banding table. (Male howlers are the loudest of all land animals except humans with boom boxes; females also make noise, but it's more like a low grunt.) Howlers are the only true folivores among the New World monkeys, eating canopy tree leaves along with buds, flowers, fruits, and nuts.

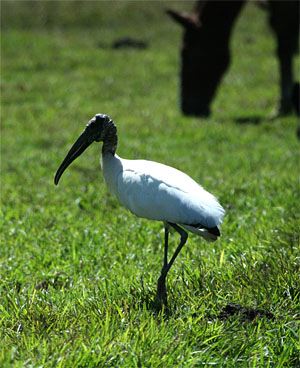

One morning as we rode our bus toward Liberia we noticed a large white bird grazing in a pasture with some horses. Its long, decurved black bill and naked gray head identified it immediately as a Wood Stork, Mycteria americana. This colonial nester is seen in parts of Guanacaste Province but is relatively uncommon in the rest of Costa Rica. Wood Storks can be found foraging singly and in groups in freshwater and marine sites, where they capture and eat fish from shallow pools. They also consume a variety of aquatic invertebrates and are known to dine on carrion.

One morning as we rode our bus toward Liberia we noticed a large white bird grazing in a pasture with some horses. Its long, decurved black bill and naked gray head identified it immediately as a Wood Stork, Mycteria americana. This colonial nester is seen in parts of Guanacaste Province but is relatively uncommon in the rest of Costa Rica. Wood Storks can be found foraging singly and in groups in freshwater and marine sites, where they capture and eat fish from shallow pools. They also consume a variety of aquatic invertebrates and are known to dine on carrion.

On top of environmental significance, Santa Rosa National Park is historically important. Here in 1856 the Costa Rican Army repelled Nicaraguan mercenaries led by William Walker, whose grand scheme was to conquer all of Central America and make it his kingdom; due in large part to Costa Rican resistance, he failed. A reconstructed hacienda in the park serves as museum and home to a colony of unidentified leaf-nosed bats (left) that hang by one foot from the rafters and spin in the wind. Costa Rica has 109 bat species, 103 of which subsist on insects, pollen, nectar, and fruit; the others are blood-lapping vampires.

On top of environmental significance, Santa Rosa National Park is historically important. Here in 1856 the Costa Rican Army repelled Nicaraguan mercenaries led by William Walker, whose grand scheme was to conquer all of Central America and make it his kingdom; due in large part to Costa Rican resistance, he failed. A reconstructed hacienda in the park serves as museum and home to a colony of unidentified leaf-nosed bats (left) that hang by one foot from the rafters and spin in the wind. Costa Rica has 109 bat species, 103 of which subsist on insects, pollen, nectar, and fruit; the others are blood-lapping vampires.

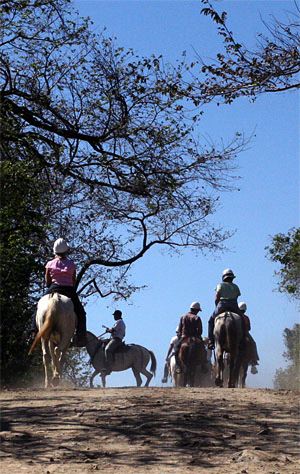

On our final afternoon at Buena Vista Lodge, the group mounts less-than-fiery steeds and trots ever-so-slowly over hill and dale toward a volcanic spa. Exploring on horseback is an interesting change--as is trying to take photos while bouncing in the saddle. Buena Vista Lodge is an old ranch that still has several hundred horses. Most are used by bus loads of day visitors who come from around the world to see the sights of Guanacaste and Rincon de la Vieja, the volcano that towers over the Lodge's comfy cabins and extensive trails. (During our 2007 week, we met folks from Germany, Denmark, Netherlands, England, Spain, and the U.S. Almost ALL who spoke English were keenly interested in our Costa Rica hummingbird work.)

On our final afternoon at Buena Vista Lodge, the group mounts less-than-fiery steeds and trots ever-so-slowly over hill and dale toward a volcanic spa. Exploring on horseback is an interesting change--as is trying to take photos while bouncing in the saddle. Buena Vista Lodge is an old ranch that still has several hundred horses. Most are used by bus loads of day visitors who come from around the world to see the sights of Guanacaste and Rincon de la Vieja, the volcano that towers over the Lodge's comfy cabins and extensive trails. (During our 2007 week, we met folks from Germany, Denmark, Netherlands, England, Spain, and the U.S. Almost ALL who spoke English were keenly interested in our Costa Rica hummingbird work.)

Oct 15 to Mar 15

Oct 15 to Mar 15